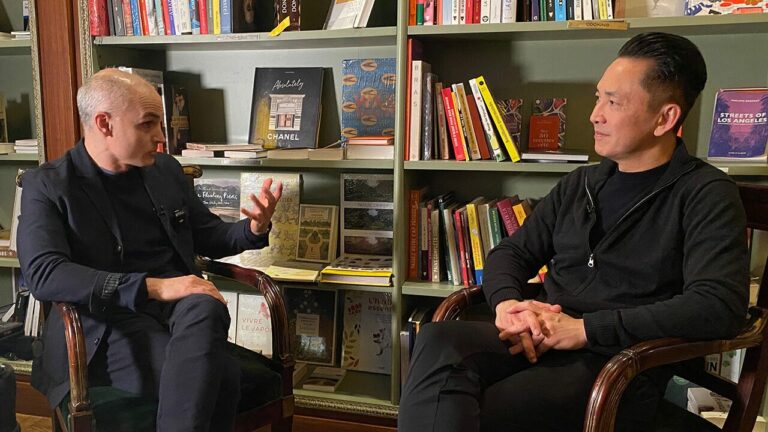

In this week’s Book Club podcast my guest is the Pulitzer prize winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen, whose new book is the memoir A Man of Two Faces. He tells me about the value of trauma to literature, learning about his history through Hollywood, falling asleep in class… and the rotten manners of Oliver Stone for The Spectator

Watch the interview here. Read below for transcript.

Speaker 1:

The Spectator Magazine combines incisive political analysis with books and arts reviews of unrivaled authority. Subscribe today for just £12 and receive a 12 week subscription in print and online. Plus, we’ll give you a £20 Amazon gift voucher absolutely free. Go to spectator.co.uk/voucher.

Sam Leith:

Hello and welcome to Spectator’s Book Club podcast. I’m Sam Leith, the Literary Editor of The Spectator, and my guest this week is the Pulitzer Prize winning American novelist, Viet Thanh Nguyen. This new book is not a novel but a memoir. It’s called A Man of Two Faces: a Memoir, a History, a Memorial. Now Viet, the first thing your readers will notice I think, is that the title of this book recapitulates in Some Way, the first line of your novel, “A Man of Two Faces,” that phrase, how are the two connected to you? Is that a deliberate stitching of them together?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Absolutely. First of all, thanks for having me, Sam, and for catching that I am a very reluctant memoirist and that’s probably a good thing. I don’t know who should be an enthusiastic memoirist and whether we should read anybody like that. But the only way I could persuade myself to write this book was to imagine that in fact, part of The Sympathizer of that novel had some autobiographical origins in me feeling like I myself as an individual had two faces growing up, and couldn’t really write about that, so I wrote a novel that was much more about someone who was much more interesting than I was. And then when it came time to write the memoir, I allowed myself to do it by pretending that I was The Sympathizer now writing about me to help me gain some distance from myself and allow my two faces to have a dialogue with each other.

Sam Leith:

One of the formal decisions you take in writing, this is quite early on after only a few pages, you flip to the second person singular. It’s a, “You” book. What actuated that decision?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

In writing The Sympathizer and it’s sequel, The Committed, I’m writing about someone who is deeply traumatized by various things, and as I was writing in his voice, I started to switch voices, for example. And there was an indication to me that this was how I was formally as a writer, trying to cope with the psychic damage and difficulties he was undergoing. And so likewise for me, it just felt actually very intuitive at the end of the first chapter to switch from first person to second person in A Man of Two Face, because the end of that first chapter ends with a shocking moment for me as a nine-year-old boy to receive the news from my brother THAT my parents had just been shot in their store and I remember feeling nothing about that moment. And I remember my brother saying, “What is wrong with you?” That is me. And looking back, I realized that was quite a traumatic moment for me and an out-of-body experience where I could not articulate myself or my feelings. And that was the beginning of me shutting down emotionally in many ways. Not the beginning, actually that shutting down had happened earlier, but nevertheless, switching a second person was an intuitive decision at that point in the narrative because it was a recognition that I was now out of my own body, looking at myself at that moment onwards.

Sam Leith:

Now that truly you describe, it’s not just personal and part of the project, the book, if I’m reading it rightly, is to talk about not just your story but your parents’ story. Can you sketch a little for our listeners what that story was, how you came, I mean you grew up in the States, but you weren’t born there, what brought you to the states?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, my parents were born in Vietnam in the 1930s, which meant that they lived through a very dramatic moment of history, 40 years for them of warfare, famine, colonizations, and becoming refugees twice because they were born in the north of the country that was divided in 1954. They fled south as refugees, had me. And then in 1975, when the war ended badly for our side or their side, they became refugees again and took me with them to the United States when I was four years of age. And so, they were refugees, I was a refugee and my memories began in a refugee camp in the United States, which was I think, sort of a traumatic moment for me as well. And so I always grew up feeling however that it was my parents who had the really dramatic and interesting lives. I was just eyewitness to their lives.

Sam Leith:

You talk about the traumatic moment coming refugee camp there is in your parents’ story before they leave, it’s kind of extraordinary, well, there’s two things that stand out, one of which is your half sister, or sorry, adopted sister, not half sister who gets left behind and then you yourself get left behind at the age of four. I mean, it’s not quite clear from the book how well you remember that, but it’s clearly something that’s seared itself into you, one way or the other. Can you talk a bit about those two little cruxes?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

My parents were devout Catholics who really wanted children, obviously, and they just were not successful, so they adopted a girl before they had my brother. They had adopted my older sister, and then a few years later they had my brother, but she was a teenager in 1975 when our town was captured in the final invasion by the north, and my father was in Saigon on business, all communication was cut off, and my mother had to make this life and death decision about what to do. So she decided to flee with my brother and me, and leave my sister behind who was the oldest, probably about 16 years of age, to take care of the family property with the assumption that we would come back. And I think that was a real assumption on my mother’s part, but of course we did not, and my parents would not see her again for 20 years and I would not see her for about 28 or 29 years.

And I mean I was four, so obviously I knew who she was, but I lost my memory of her. And so, the first time I think I realized I actually had an adopted sister was when I was 10 or 11. And this letter shows up in our American home from her with a picture of her, this time as a young woman in her 20s, and beautiful woman in black and white photograph. And I think I asked, “Who is this?” “This is your adopted sister, [foreign language 00:06:18].” And that was the beginning of my understanding that we had a ghost in the house, a person who was not with us, an absent presence. And it really haunted me for quite a long time to think about who she was and what had happened to her. And that could have happened to me. And I think for a lot of refugees, there is that sense of a parallel universe where if something different had happened, we would’ve had a completely different life.

And I ended up in the United States, I was the comparatively lucky one. And in this refugee camp in Pennsylvania, you had to have an American sponsor you to leave the camp, but there was no American willing to sponsor my entire family of four. So one sponsor took my parents, one sponsor took my 10-year-old brother, one sponsor took four-year-old me. And those were my first memories howling and screaming as I’m being taken away from my parents. It was being done for benevolent reasons, but when you’re four, you don’t really understand that; I only understood fact that I was being taken away from my parents. That was a pretty cohesive memory, that was a beginning and middle and an end to that memory. And that was where narrative memory really began for me.

Sam Leith:

As your parents made their lives in the States brought you up, was this trauma something they talked about? I mean particularly the absent presence, losing a daughter must have weighed on them, I’d have thought very heavily indeed.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think they transmitted a few stories and some of those stories appear in the memoir, but they were completely random. They never gave me a cohesive narrative of their lives from birth till my origins or my memories beginning. And so, the stories that they would tell me would just sort of appear out of nowhere, out of no context. It would be just really shocking for me to try to make sense out of what they were telling me, as basically as an American boy growing up without ever having read Vietnamese history, ever knowing really what happened to our country.

So for example, I was again, I think eight, nine 10 years old, and I was plucking hairs from my mother’s head, gray hairs for which she was paying me a nickel. And out of nowhere she says, and at this point I think she would’ve been in her mid-40s, she said, “Oh, in my village when I was a child, there was a famine and there was a dead girl on a doorstep.” What do I make out of that story, mom? And I had no idea what to say, and my Vietnamese was not great either, so it’s not as if I could ask complex questions about what had happened or how she felt. And that also stayed with me as well; there’s a moment of just this eruption of history without context, and that was so much of how in my own household I experienced reality of history.

Sam Leith:

[inaudible 00:08:49] the form of the book, I’m interested in how you chose to structure it and also some of the decisions you’ve taken about it. It’s typography for instance, quite unconventional, it’s sort of broken, you’ve got sections set, right? It’s sort of, sometimes you have a large type. Was that just you having fun or was there an attempt to capture some of the choppiness of this memory process or remembering the present?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think it was all of that. I think the book is about memory as content, so there’s specific stories and so on, but it’s also about my own relationship to memory that, I don’t know who has a very smooth, linear relationship to memory, or maybe Vladimir Nabokov in Speak Memory, which was a book that I looked at. And he very carefully reconstructed his childhood by consulting his siblings, for example, and his relatives and writing in lush, full paragraphs and prose. And I decided as beautiful as that was, that was not my project. My project was about my own fragmentary experience of memory, that my memory jumps around all the time, and there are gaps in my memory, which I could try to fill in through research, but there are also gaps that I did not want to fill in through research. So the prose and the structure expresses that so that the reader feels some of that as well.

But honestly, as with the decision to switch into second person, so much of this was intuitive. It just felt right. And by that I mean, I was having fun writing this book despite its very heavy content in many places, and I gave into the spirit of fun. I have children, I read children’s books with them, and one of the most remarkable things about good children’s literature is that there are no rules. An author, illustrator can do anything they want and children will go along with it as long as it’s entertaining. And that’s how I felt about writing this book. I should be able to do whatever I want as a writer. And I was so frustrated by this idea, I think, that those of us who write prose, whether it’s fiction or nonfiction, seem to be very tightly bound by certain kinds of conventions, whereas children’s book writers and poets have no such expectations. Poets can do anything, and no one says anything about things that poets make. They’re expected to make formal decisions of all kinds. But my book, when people look at it, they’re like, “It’s unconventional” and there’s nothing in the book that happens that hasn’t been done elsewhere, I think, it’s just that typically doesn’t happen in memoir like this.

Sam Leith:

Now you a literary scholar and you were a literary scholar before you came to be a fiction writer, and I get a sense this book’s quite shadowed by these ideas of genre. I mean, there’s this particularly I think brilliant scolding passage in the middle where you say, “Here’s how you write your own traditional immigrant saga. This is the memoir that this book isn’t going to be.” I mean, was that something you were always kind of fencing with in this book?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, absolutely. I mean, the good and the bad thing about being a scholar of a certain subject is you do have to read everything or as much as you can in that subject, which laypeople don’t have to do. And so with laypeople, if we talk about this immigrant narrative, for example, immigrant genre autobiography, your typical reader will only read a handful of these books, and hopefully will read the good ones or the best ones, but if you specialize in it as a scholar, you have to read all of it. And then so in that case, do think I know what that genre looks like, and what its features are, and which are the good ones and the bad ones.

Besides the fact that there are good and bad versions of the immigrant narrative in the United States and possibly in the UK as well. The problem is that when readers read these books, they also bring along with them I think, typically the ideological expectations of the country. So for Americans, the idea of the American mythology, American exceptionalism that we have the greatest country on Earth, the American Dream, that everyone can achieve whatever they want, these are ideas that Americans hold like a religion inside of them. It’s very difficult for Americans to let go of these ideas. And so, no matter what your narrative is saying as an immigrant, no matter what, the typical American response will be, “Well, you achieve the American Dream by getting to this country and writing this book. Welcome.” And they will completely overlook all of the various kinds of contradictions that might exist in the narrative. And so, I am very conscious of that, and I did not want this book to be labeled in that fashion. I wanted to push back against my readers, and push back against their expectations of what a book like this is supposed to do.

Sam Leith:

Now, the experience of if you like, the growing up, as you say in these sort of slightly squirreled and square quotes, “A model minority,” the doubleness, you talk about, the doubleness of self is sort of doubled in that sense that the experience of Vietnamese migrants is both sort of held above, again, the sort of anti-Black racism, and yet also still not white. How did you negotiate that, and did that change as you were growing up? Because your parents very much bought the kind of American Dream line, if I understand it correctly from you, and you started to rebel against that in your teens, is that right?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think so. I didn’t see themselves, my parents did not see themselves as Americans, but I think they certainly did… They were very good capitalists, and so they fit easily into American capitalist culture. And I grew up in California in a city called San Jose that is predominantly white, Asian and Latino, there weren’t that many African-Americans there or even now. But of course, the issue of the Black and white divide in the country pervades everything in terms of politics, popular culture and so on. So I had to learn how to learn my own history as an Asian refugee, Asian immigrant, Asian-American, but also the complicated racial history of the United States as well. And I studied all of that very seriously in college.

And the sad thing about it all, I think, is that even though I specialized in that in college, there were still so many things I never really learned or understood. And that’s because I think the United States, like other countries, does a very good job of submerging the controversial aspects of its history, even for the specialists. So I grew up in California and besides anti-Black racism, let’s just say that modern California would not look the way it is without the genocide of Native Americans, of Indigenous peoples, and that’s something I never really had to think about or confront, and it’s been an ongoing project for me even up until the present, just realize just how terrible that history has been in California, but also the United States.

Sam Leith:

Before you came to study history properly and seriously at college, your first appreciation of the world from which your parents came and where you were born was the 1980s kind of burst of Vietnam movies. So much of this is refracted through a cinematic lens, isn’t it? How did that affect you as , I guess, teenager at that stage kind of watching Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, all those movies?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I think it affected me very, very deeply. I mean, Hollywood is very powerful. It’s the unofficial ministry of propaganda for the United States, and I don’t think we should underestimate the power of pop culture and soft power. And the United States fought the war again in memory via these Hollywood Vietnam War movies, which were really global in their impact, I think, especially for people of that generation. I think maybe less so now, because my own students in their 20s, most of them have never seen a Vietnam War movie. So we’ve gone from a situation in which Vietnam, the war was seared into the global consciousness by history, but also by American media, now to the point where it’s almost forgotten in some way.

Sam Leith:

It sort of came 10 or 15 years after, didn’t they? There was this wave of them, I remember.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, yeah, it began, I started as late as the 1960s with John Wayne’s The Green Berets, which is just American propaganda, but starts to become very artistic in the late ’70s with Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, the movies you mentioned and continued into the 2000s. And as a young American growing up, this was how I learned my Vietnam War history is through these movies. But besides that history, shown through an American perspective, I was also deeply impacted emotionally by how the Vietnamese were represented, or misrepresented, or seen through in these movies because we just came off terribly. We were voiceless, we were terrifying, we were the victims or we were the victimizers. We were certainly never human, in most of these movies.

Sam Leith:

Startling thing you say, which I hadn’t thought at all, because white privilege and so on, is that in the credits of Apocalypse Now, nameless white characters all have names in the credits and the Vietnamese characters, even where they have lines in the thing are just like, “Third Soldier.” Is that the same across the board, or is that particularly Apocalypse Now’s problem?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, no, it’s worse than Apocalypse Now because let’s say you’re the door gunner on a helicopter, a white guy, your name appears in the credits. You don’t have a name as a character, but your name appears in the credits. All these Vietnamese people appear in the movie, getting murdered, or killed, or whatever, and at least one of them has a line where she throws the hand grenade into the helicopter, but nobody actually appears in the credits. There’s no Vietnamese people credited in the credits. It’s a total erasure. And of course, the irony of it all was Apocalypse Now was shot in the Philippines, and these Vietnamese characters were all drawn from the Vietnamese refugee camp. These people had fled from Vietnamese communism, and they ended up portraying Vietnamese communists in the movie. It’s so absurd that I had to satirize it in my novel, The Sympathizer.

But in general, this is what happened to the Vietnamese in these Hollywood movies. Most of them, if they appeared in the credits at all, their names might appear, but then they would play characters like Da Nang Hooker, for example, in I don’t know what it was, Full Metal Jacket perhaps. And so it was very rarely the case that you had characters with speaking roles and with actual names versus these types that they portrayed.

Sam Leith:

That’s extraordinary. Have you ever come across, and certainly, it’s complete parenthesis, A.L Kennedy’s novel, Day?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I’ve not, no.

Sam Leith:

Oh, it’s got a whole thing about people who were in prison of war camps playing prisoners of war, kind of chimes with me. There’s a fantastic piece of gossip in this book, also, I have to ask you about, you say the character in The Sympathizer, who’s this author director who isn’t Francis Ford Coppola, but might be a bit like him, but could be another character, you say, a mutual friend had you sign a copy of The Sympathizer for this director and you later saw it on eBay. Who was that, come on, name and shame?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I don’t care personally, it was Oliver Stone, I think. Yeah, I had no desire to sign this book to Oliver Stone, but I did care for my friend who will go unnamed here, because he knows her, and that was his birthday present. It was a limited edition. It was a Pulitzer Limited Edition, I think, of The Sympathizer, and I joked about it. I put it on Facebook, I think, and then one of my friends actually went and bought the book. It was a $500 book. I never would’ve spent that much money to recover my own work, but he did. So I think the theory is that the book was probably, I think was found in a local public library. Stone, or one of his people probably just donated the book to the library. And then the guy-

Sam Leith:

I was thinking, Oliver Stone probably didn’t need $500 bucks at this stage-

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

No, I’m sure, I mean, it would just be perfect if he was, but it was somebody else who made a killing accidentally, off of finding this at the public library.

Sam Leith:

It’s extraordinary. Now, you were academic before you were a writer, was that for you kind of… I mean obviously you’re an academic writer, but before you’re a novelist, I should say, a fiction writer, was that for you a kind of holding pattern or was that a sort of necessary precursor to doing your work?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think it was both. It was a holding pattern in the sense that I thought of being an academic, and I still am, I’m still a professor who teaches. I thought of it and think of it as a day job. It was something to hold off my parents, because my parents obviously wanted me to be a doctor, or a lawyer, an engineer. My older brother became a doctor, a medical doctor, the real doctor. I became a PhD in English, which is a fake doctor, right? And I think they were tolerant enough to let me do that, but they still wanted me to have a job, so I became a professor.

But at the same time, being an academic infused me with all kinds of ideas, and theories, and bodies of knowledge, and methods that I think have been in the end, enormously useful for me as a writer. I think that training and that mode of thinking has made me a different kind of novelist, for example, than a lot of other novelists who, in the United States, came up through what I call the Industrial Pipeline of creative writing. That is they majored in creative writing, they did master’s degrees in creative writing, and they’re steeped entirely in this world of what’s called, “Creative writing” in the United States, which is a term I totally object to. And-

Sam Leith:

You talk, in the book about why you object to it. Can you expand on that a little? I’m interested in-

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

As a writer, shouldn’t you be creative? Isn’t it a sign of anxiety to have to say, “I’m a creative writer.” Did Hemingway call himself a, “Creative writer?” This is just so strange to me, and in the world of the United States, which pioneered the writing workshop model, which has now apparently become globalized in a certain way, there’s also this idea not just of creative writing and the workshop method, but of craft. And I object to that too, because I think of what I do as art, not as craft. There’s nothing wrong with craft, but at the same time, if you’re going to say, “Craft,” what about labor? And in the world of creative writing in the United States, there’s very little attention paid to labor, but there is to this idea of craft. So it just seems weird to me in so many ways that we’re going down that road.

Sam Leith:

Do you teach writing, incidentally?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, no, I don’t teach writing. I don’t even know how to teach writing. I do work with writers, and we have a Creative Writing PhD program. I sit on dissertation committees where I read people’s novels, and poetry collections, and short story collections. So I work with writers one-on-one. That’s a kind of teaching, I think, but it’s different than trying to teach 12 or 14, 20 year-olds or even 25-year-olds how to write. That part, I don’t understand how to do.

Sam Leith:

A theme of the book is that you say, emotional damage is a sort of prerequisite or an enabler of writing or the sort of writing you do. Do you feel that that specifically applies to you, or do you buy the idea that actually, in a sense, I mean I think you describe your teacher Maxine Hong Kingston saying, “Cut to the bone. That’s where you’ll find the good stuff.” Is that just one sort of writing, or do you think it’s a sort of universally true of writers that, essentially damage is what makes them write?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think there’s obviously forms of writing that don’t require that. I speculate that maybe journalism doesn’t require that as often, but at least for the kind of writing that happens in what we call literature, poetry, memoirs, novels and so on that are not there purely for entertainment, but are there supposedly to serve some other kind of artistic, or spiritual, or emotional purpose, I think there probably is emotional damage for most writers. The degree of that emotional damage may vary. I don’t think it necessarily has to be as traumatic as surviving sexual abuse, or anything of that degree, although that will also do this as well. But it seems like many writers I know have some secret core of emotional damage that they have dealt with, or are working through, which provides some of the motivation and also the material for the writing.

So for example, in my own work in the fictional work, I’d write about people of many different kinds who are not me, and I’ve never done the jobs that they’ve done, for example, but their emotions come out of me. And so, the emotional damage that I’ve felt as a person, and the way that I’ve tried to grapple with it as an adult has provided that emotional sustenance for these characters in this work. But also it has provided me the motivation to keep on writing as well.

Sam Leith:

Yeah. Well, I mentioned Maxine Hong Kingston, she was obviously a hugely important figure to you. Can you tell me a little about how she set you on the path you’re on now? Because by the way you describe it, I was thinking, “He’s as a Pulitzer Prize winner, he’s a professor,” I was kind of expecting reading this book that you’d be this prodigy from a young age that you’d be AAA student, and it sounds like kind of the opposite’s true.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah, I struggle with a lack of motivation. What I was motivated about was reading. I loved reading. I did that on my own all the time, and that was my way of fantasizing and escaping from this refugee world that I’ve described. But I was a failure as a student, relatively speaking. Again, my brother set the standards. He came at 10 years of age, didn’t speak English. Seven years later, he was going to Harvard, then he went to Stanford, and so on and so on. And that was what I was supposed to do. Instead, I kind of was a mediocre student in high school, didn’t have any motivation. Finally worked my way up to the University of California at Berkeley and got into this class with Maxine Hong Kingston, who in 1991 was a very famous writer of the woman, Warrior Chinaman, Tripmaster Monkey. I was 19 years old, what did I care? I knew who she was, but I did not care in the sense that I didn’t think I should be reverential or anything. So I got into this very competitive, 14 person nonfiction writing class, and I would sit a meter away from her every day, and then every day, I would fall asleep in her class.

And I have my reasons. My own reasoning was I’m a political activist, I’m up late every at night planning stuff and all this kind of thing. And then she wrote me a letter at the end of the semester saying, “You seem like you are deeply alienated and you should make use of the university’s excellent psychological services.” Obviously, I never did. Instead, I became a writer. I was the worst student in her class. She said that. And at the same time, I don’t think that’s a discredit to her pedagogy. As a teacher myself, I think I realized that students respond differently to different moments in their lives, and it’s very difficult to figure out how students are learning things. And sometimes there’s a delayed effect to pedagogy. And I think that was true for myself and Maxine, that I did absorb a great deal from reading her work and teaching her work, because I teach The Woman Warrior all the time, but the emotionally at 19, I wasn’t ready to grapple, both with what she demanded from me as a student, but also what my writing demanded from me, because I started writing about my mother in that class, and it was so emotionally painful that I think I just could not handle it. And she was right. I was deeply alienated, and I just did not know how to deal with it, even through my own writing.

Sam Leith:

As you say, you’ve started to write about your mother, the traumatic episode with your mother, which was a period of mental illness when she was taken out of the home, and the most extraordinary thing in here. As you say, you thought this happened when you were much, much younger and you were, I think 19 or something when that-

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I was writing about it when I was 19. It happened when I was 18, and I put the essay away and did not look at it again for 30 years. And the pandemic compelled me to go back and look at things, and I reread the essay, and I was struck by the fact that for the past 30 years, I’d remembered my mother’s going into a psychiatric facility as happening as you said, when I was a small boy. And here it was. I was a young man when it happened, and somehow, even as a young man who had written it a 10 page essay about it, my memory still was able to convince me over the next few decades of something completely different. And if I had not written that essay, if I had not kept it, I never would’ve realized what actually took place.

And so I did not even remember 90% of the things I mentioned in that essay. And so, then I felt as a writer, this was a sign among several other signs that I really needed to write about this experience and to connect what happened to my mother with my own life, certainly, but the life of Vietnam and the United States.

Sam Leith:

Do you see what happened to your mother as a sort of deferred trauma response to her young adulthood?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

It’s so hard to say. I think that there were certainly things that were unique to my mother that had to deal with her biology and her psychology that I will never know and never understand. And then, I think that there were things that were inevitably about the trauma of the experiences that she underwent. She and many other people underwent those traumas, and I saw the collective results of that in the Vietnamese refugee community, that there were so many different forms of mental illness, emotional distress, domestic violence, and other kinds of manifestations of what had to be traumatized behavior. And so, I think my mother was simply on one far end of that spectrum of emotional traumatic fallout. And then, that was combined with her own mental illness as well.

Sam Leith:

Your parents had a bookshelf with no books on it, and obviously, you were intensely bookish child. You had language that, to some extent, took you away from them. In some ways, this is one of those stereotypical sort of immigrant story tropes, but you were taken away from your parents by language, by education, geographically, and also did politics. I mean, you said when you went to Berkeley, you’ve got quite a proud little paragraph where you list like, “This is the number of times I was arrested. This is the number of protesters involved in” you were really, you were as in your own words, “Radicalized.” Was that something that helped you understand your parents better, or did it sort of take you away from them, given that they were busy, as you say, being the model minority?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think both. I mean, obviously the radicalization took me far away from them in terms of what they believed and what I believed. They were devout Catholic capitalists. They sent me to Catholic school my entire life, and despite all that, I came out an atheist went to Berkeley, I became a Marxist. And yet at the same time, I think that my study of things like capitalism, and colonialism and so on in fact helped me understand my parents better. And one of the things that I’ve concluded is that in fact, Catholics and communists have a lot in common. They just believe in different gods. But everything else; the suffering, the sacrifice, the collectivity, the desire for martyrdom, the belief in utopia, all those things are the same. And so in some ways, I still think I’m very much my parents’ child, in the sense that I’ve absorbed so many of their values, even if I didn’t absorb the facade of Catholicism, for example. And my politicization, and my radicalization gave me a deep empathy for people who are classified as, “Others,” which Catholics do as well.

And then finally, my long emotional trajectory as a human being has taken me to the point where I’ve grappled so long and so often with things like race, and gender, and colonialism and nationalism as forms of otherness, that I’m now able and ready to talk about the otherness of other people. And this conclusion that sometimes the people who are most other to us are the people right next to us. That would be my mother and my father. I mean, I should know them so well, and yet I don’t know them in so many ways and probably vice versa. And that is an outcome of our history. And that, to me, is fascinating. The intersection of these big political ideas and calamities with these small calamities of one’s domestic life.

Sam Leith:

It’s actually an extraordinary detail that you make the point that you say your parents’ people, though they were obviously colonized, were also colonizers in the North, the Montagnard people who were originally, they were sort of driven out, and the book’s full of these sort of doublenesses. I mean, one of them, you talk about the difference between the, “Ugly American and the Quiet American” as these do these. Can you talk a little bit about that, how you see those things play out?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, the book is about memory and forgetting, individually, but also collectively. And of course, one of the things that binds us all together as humans is that we all have selective memory. We like to remember the better things about ourselves and our countries, and forget the worst things. Americans certainly do that, but some of the Vietnamese. And so if you go to Vietnam, for example, and you have absorbed any history of the country, it’s always probably going to include the fact the Vietnamese will say, “The Chinese colonized us for 1000 years, and that’s why they’re are real enemies and are real competitors” and so on. But I’ve never heard of Vietnamese person of my background, I’m part of the majority ever acknowledge that we in fact, colonized these so-called ethnic minorities of whom there are dozens in Vietnam. And if we do mention the fact that all of Vietnam is built from imperial conquest, and that the southern half of Vietnam has been taken away from the Cham people and from Cambodians, that’s as treated as a fact of Vietnamese history, it’s not treated as something awful. It’s simply, “Well, of course that’s why we are great people.”

And again, not any different, I think, or not very much different than how Americans have looked at their own history. And so, I just use these extreme opposites of the Quiet American and the Ugly American to argue that, of course, the ugly American is someone like Donald Trump, and it’s easy for Democrats-

Sam Leith:

It’s always blacked out in your book, I noticed.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yes, I redacted his name in the book out of sheer pettiness, but also out of acknowledgement that redaction is a part of America, a part of the United States. I mean, I grew up in a time where, as an adult, I’ve seen so many redacted documents, and documents out of Guantanamo Bay, for example. So redaction is a literal way by which the United States government gives its own citizens censored information, and to me, symbolizes the way that, for many Americans, our imaginations have been censored. We do not, for many of us, have a very good understanding of what it is that the United States does as a military and global as power.

And to go back to the Ugly American-Quiet American divide, again, it’s easy for liberals to point at Donald Trump as the Ugly American and dismiss him when in fact it’s the Quiet Americans like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, very nice mannered, intelligent men, people, and Hillary Clinton and so on, who are the ones who also authorize all kinds of things like drone strikes, and humanitarian wars and things like this. And so, Ugly Americans and Quiet Americans have great political conflict domestically in the United States, and they have some conflict in terms of foreign policy, but they are definitely unified around this idea of America as an exceptional country.

Sam Leith:

Now, when you talk about the reception of The Sympathizer, which was obviously a colossal success, it won the Pulitzer Prize it sold, as you say, even though your father couldn’t and didn’t read it, he took great pleasure in this sales figures and so on. But I said this a kind of discomfort as you describe it in your response nevertheless, to how that book was received. I mean, you quote rather kind of archly the New York Times’, “It gave voice to the voiceless” quote. And you talk about saying, “I’ve become now, I’m a professional Vietnamese, I’m a professional refugee.” How do you frame that dissatisfaction?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, well, there’s nothing dissatisfactory about winning a Pulitzer Prize, or selling a million copies and all that. I’ll take that any day. But there’s a real temptation to believe in one’s own publicity, one’s own hype, one’s own reputation. And I feel very self-conscious about that because as a scholar of literary history, I know where egos tend to lead writers. And I also know that things like literary awards, and book sales and literary celebrity are very ephemeral things that may not survive the passage of time and an author’s death. And I’m also very aware, again, of how people like me are easily exploited by the machinery of publicity, and sales and so on.

And I’m not the first person to use this idea of the professional Vietnamese. That inspiration comes from Hanif Kureishi and his idea of being a professional Pakistani. I think he might’ve been first one to point that term in that context. And I think these terms are important because we have to be self-conscious about our own commodification and professionalization. In many ways, we have no control over that, but we do participate in that, that we can control. And I do participate in that mechanism of being a professional Vietnamese to some extent, because it allows me to get opportunities to speak, and say the things that I believe in, which not everybody may agree with. So I try to exploit that opportunity where I can, and yet to also draw attention to that mechanism, so that I’m not naively participatory in my own marketing and this language of, “Platforming,” which I find so offensive as well.

Sam Leith:

Why do you find, “Platforming” an offensive idea? I know a lot of people in progressive circles would say, “Platforming, that’s a good thing.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I just object to all this language about influencing and platforming and so on, I think there’s this, maybe it is some conservative, highly elite, snobbishly literary part of me from education in the library where I still believe in art over things like influencing, and having a platform. Having a brand, for example, that kind of language just seems to speak so immediately to the ways by which, even things like thought have been commodified, so now we have thought leaders. Well, that whole discourse, all that jargon is very difficult to separate from social media and the fame machine that is a part of that right now.

Sam Leith:

Purely literary terms, towards the end of the book, you start to talk a little bit about the sort of framing or the way in which creative writing is thought about, and you take issue with this cliche of, “Show don’t tell,” and you say, “Representation isn’t good enough.” Can you explain a bit how you feel we have to kind of change the way in which literary writing is understood?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I mean, obviously the whole idea of literary writing versus the so-called genres of writing is that literary writing is supposed to be premised on originality and authenticity, and yet at the same time, it’s not immune from certain kinds of cliches, which would include, as you mentioned, this idea that literary writing should never tell, and this other platitude that representation matters. And if we’ve been misrepresented, or underrepresented, or not represented at all, we should represent ourselves. So, “Show don’t tell” is obviously an important aesthetic. I appreciate it too, but I also appreciate a good dose of agitprop, satire, didacticism at times. I think these are all different strategies that can be used. And then, if you go back to other forms of writing besides contemporary western fiction, if you go back to The Bible for example, there’s lots of didacticism in there; there’s parables, there’s fables. So there’s so many different forms of storytelling that can be accessed by writers. But whatever reason in the world of, so-called creative writing, it’s been narrowed down to this dictum of, “Show don’t tell,” which then becomes a cliché.

And for people like me, again, the so-called Professional Vietnamese, Professional Immigrant or Asian, or whatever person of color, “Show don’t tell” intersects with representation. If your story is not out there, then you go tell your own story and you will have your niche there and the publishing world will eat it up because that’s how the publishing world, like every other industry needs new commodities and representations feed into that. And so, the slogans of like, “Representation matters,” it’s very powerful, it’s very necessary because I would certainly rather have more representations than less of any given population. But again, that idea of just purely having more representations is easily, easily co-opted, first through this ghettoization of people into being able to represent only themselves, and second, separating representation from things like political critique and decolonization, which I’m deeply invested in as a writer and as a scholar.

Sam Leith:

Yeah. Is that co-optative aspect, because some would say that the publishing industry is more open now to the voices that are traditionally been, “Other.” And as you describe, I think when you were looking at doing postgraduate work, you said, “I want to study Vietnamese American Literature,” and I think your supervisor said, “That’s nuts. Nobody will hire you.” Do you think that’s changed, and has the change been positive, or has it change essentially been, as you say, pigeonholing, co-optative and essentially, commodifying?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I think all those things happen simultaneously, so no doubt it’s a positive overall. And in fact, in my PhD program after me, there were students who did Vietnamese American Literature as their dissertation. So we made progress. And of course, if you go to the bookstore, online or in person, it’s better that there are more stories about different populations rather than having none of them. So all of that is out there, and yet at the same time, I think because a publishing industry is an index of society at large, it’s not immune from the ways that society itself is still deeply beholden to capitalism, at least in the UK and in the US, and to various kinds of prejudicial and patronizing attitudes.

So again, for example, in my case, I think I felt that when I was writing my first novel, The Sympathizer, I felt that I was caught in a contradiction, which is, on the one hand, the Vietnam War novel is, “Nobody wants to read that anymore,” is what I was being told. And so that if I was supposed to write about something, I was supposed to only write about Vietnamese refugees, and so what am I supposed to do in that kind of a scenario? There’s all these categories and pigeonholes that have been created, and obviously, many people have recognized that, and that puts the writer of color just to choose one category into a conundrum, because then they’re told that if they write about their own background, they’re participating in their own ghettoization. But then if they don’t do that, then they’ve somehow whitewashed themselves and they’re not writing about their own people, or their community, or the history or whatever. So we’re caught in a total conundrum.

And so The Sympathizer was my way out by going directly into the heart of things, “The heart of the matter,” to quote Graham Greene, “The Heart of Darkness,” to quote Joseph Conrad by writing about the Vietnam War from a Vietnamese refugee experience, and not just talking about Vietnamese refugees, but talking also about the United States. That’s what we’re not supposed to do. This idea of, “Representation matters” means that a Vietnamese refugee only talks about Vietnamese refugees, but not about the United States. That is the space for white men to talk about, right? That, at least was my perception of how, “Representation matters” works to include and exclude someone like me at the same time, which is why I think The Sympathizer is an unsettling novel for some readers because they are not used to having this history talked about from a Vietnamese perspective, because we’re only supposed to talk about ourselves.

Sam Leith:

Viet Thanh Nguyen, thank you very much indeed for your time.