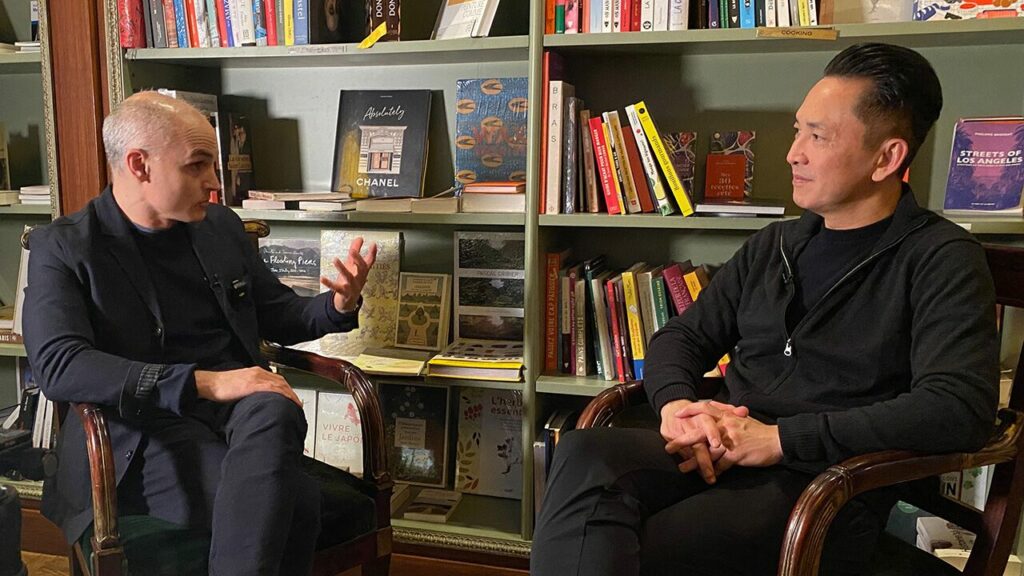

What can a novel about wealth in America tell us about America? In this podcast episode, 2023 Fiction winner Hernan Diaz is in conversation with Pulitzer Board member and 2016 Fiction winner Viet Thanh Nguyen in New York City. Together, the authors discuss Diaz’s “Trust” and “In the Distance” (a Fiction finalist in 2018), as well as Nguyen’s “The Sympathizer” for Arizona PBS

Listen to the conversation here

Diaz and Nguyen explore some of the key mythologies behind America’s exceptionalism, especially around money and capital, and the mythical idea of the West. As Diaz says, “There is something about this country and its culture that invites fiction, and not all of these fictions are pleasant.”

The authors consider some of the mythmaking about America they encountered as early readers. Both authors left their home countries and landed elsewhere as refugees, Diaz in Sweden and Nguyen in America. The authors talk about how these experiences impacted them and share their personal journeys of discovering books and the power of literature. They discuss the perils of book bans and censorship. With censorship, as Nguyen puts it, “We don’t just lose the power of literature and all that stuff that we like to talk about as writers and readers; we lose the power to address some very fundamental core elements and problems of what make us Americans.”

Both writers share what it’s like to have their novels adapted for the screen. Diaz’s “Trust” is currently in development with director Todd Haynes (“Velvet Goldmine”) with actor/executive producer Kate Winslet slated to portray the character of Mildred Bevel. An HBO miniseries adaptation of Nguyen’s “The Sympathizer,” co-created by Park Chan-wook (“The Vengeance Trilogy”) and starring Hoa Xuande and Robert Downey Jr., premiered on April 14, 2024.

A full transcript of this episode is available here.

Learn more about our guests in this episode:

Hernan Diaz is the author of two novels translated into more than twenty languages.

His first novel, “In the Distance,” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner

Award. He has also written a book of essays, and his work has appeared in “The Paris

Review,” “Granta,” “Playboy,” “The Yale Review,” “McSweeney’s,” and elsewhere. He has

received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Whiting Award, the William Saroyan International

Prize for Writing, and a fellowship from the New York Public Library’s Cullman Center for

Scholars and Writers. Diaz is the associate director of the Hispanic Institute for Latin

American and Iberian Cultures at Columbia University, and serves as the managing

editor of the Spanish-language journal “Revista Hispánica Moderna.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s novel “The Sympathizer” is a “New York Times” best seller and won

the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, the Andrew Carnegie

Medal for Excellence in Fiction from the American Library Association, the First Novel

Prize from the Center for Fiction, and the Asian/Pacific American Literature Award from

the Asian/Pacific American Librarian Association, among many others. His other books

are “The Committed,” a sequel to “The Sympathizer,” “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the

Memory of War” (a finalist for the National Book Award in nonfiction and the National

Book Critics Circle Award in General Nonfiction) and “Race and Resistance: Literature

and Politics in Asian America,” as well as the bestselling short story collection, “The

Refugees.” He is the Aerol Arnold Chair of English and a Professor of English, American

Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern

California. Most recently he has been the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim

and MacArthur Foundations, and le Prix du meilleur livre étranger (Best Foreign Book in

France), for “The Sympathizer.” He is the editor of “The Displaced: Refugee Writers on

Refugee Lives” and the Library of America volume for Maxine Hong Kingston. He

co-authored “Chicken of the Sea,” a children’s book, with his then six-year-old son,

Ellison, and his most recent book is a memoir, “A Man of Two Faces.” An HBO miniseries

adaptation of “The Sympathizer,” co-created by Park Chan-wook (“The Vengeance

Trilogy”) and starring Hoa Xuande and Robert Downey Jr., premiered on April 14, 2024.