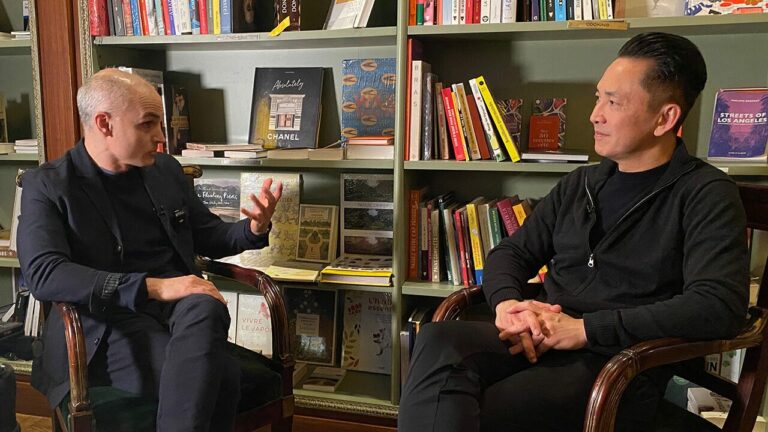

Is the near-universal game of “cowboys and Indians” just positive propaganda for genocide? When a Vietnamese-American watches ‘Apocalypse Now’, does he identify with the victim or perpetrator? As the Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s book ‘The Sympathizer’ comes to HBO, we explore these themes and discuss his triumphant new memoir, ‘A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial’ for Monocle Radio

Listen to the interview here. Read below for the transcript.

Georgina Godwin:

Hello, this is Meet the Writers. I’m Georgina Godwin. My guest today is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Sympathizer, which has sold over 1 million copies worldwide. He’s also the author of several works of fiction and non-fiction, including the best-selling collection of short stories, The Refugees. He’s the Errol Arnold chair of English and a professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. He’s a regular contributor and op-ed columnist for the New York Times, covering immigration, refugees, politics, culture, and Southeast Asia. In 2017, he was awarded a MacArthur Foundation Fellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowship. In 2020, he was elected as the first Asian-American member of the Pulitzer Prize Board in its 103-year history. Absolutely honored to be joined by Viet Thanh Nguyen. Welcome to Meet the Writers.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Hi, Georgina. Pleasure to be here.

Georgina Godwin:

So, we just met earlier this week in Washington where we were doing some events. And we had some quite late nights there too, I have to say. And we’d both just flown back to England. So, we’re revving up that energy. But I’m sure that we will, because this book was just extraordinary. It just affected me so much. And made me think about things that really hadn’t occurred to me before because this is not my world. Now, I was very careful in the introduction not to introduce you as a Vietnamese-American. And of course, that is one of the key themes throughout the book, and also to try and get the pronunciation of your name right. So, labels matter, don’t they?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, of course, labels always matter. And I think we recognize the importance of labels when they’re applied to us or not applied to us as the case might be. So, the example that you brought up Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Vietnamese-American writer, often used for me. And I don’t object to it in and of itself because I am a Vietnamese-American and a Vietnamese-American writer. However, what I do say is if I am a Vietnamese-American writer, then Jonathan Franzen should be a white male American writer, and so, on and so forth. So, it’s either labels and adjectives for all of us, or labels and adjectives for none.

Georgina Godwin:

Yeah. Now the same applies to the word refugee versus migrant, immigrant, exile, and so on. Just unpack a little of that for me.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think these are all loaded terms. They have different meanings. In the context of the United States, we favor the idea of the immigrant. Because the immigrants actually reinforce Americans images of themselves as the greatest country on earth. So, of course, immigrants want to come to the US. Refugees are scarier for a lot of people, not just in the United States, but the UK and in many other places because they bring connotations of failed nations, failed states, and they threaten to overwhelm. And so, the refugees become the objects of our fear rather than subjects in and of themselves who I think bring news of a changing world that many of us have not yet grappled with.

Georgina Godwin:

And in your book, you really dissect this idea of being the model citizen. You are there to be the best that you can possibly be. You reference Dina Nayeri, the ungrateful refugee, and talk about how you have to be that representative. Rabih Alameddine, like you, representative of all Lebanese. And is that something that you feel the weight of?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, absolutely. I have seriously half jokingly call myself a professional Vietnamese because I’m caught on to speak about that issue about being from Vietnam, being Vietnamese, the Vietnam War, and so on. A professional refugee talking about refugee issues. And again, I don’t mind speaking about those things. But I’m also an American and I would like to be able to speak about the United States, which oftentimes, people such as myself are not invited to do. And in this book, I assert my voice in that regard as forcefully as I can.

Georgina Godwin:

You absolutely do. It’s very much a book about America. Let’s just talk about your own background, because of course, this book is a look back at your life, particularly at the lives of your parents and what influenced them. You were four years old when this story started. Just run us through the biographical detail.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I was born in Vietnam during the war, the Vietnam War. And in 1975, my family was on the losing side, so we fled as refugees. And I was there for the fall of Saigon, but I can’t really claim to be an eyewitness. And so, I can’t remember it. But my memory start when I was four in a refugee camp in Pennsylvania in the United States. And in order for Vietnamese refugees to leave that camp, we had to have Americans sponsor us. But there wasn’t an American willing to sponsor all four of us. So, one sponsor took my parents, one sponsor took my 10-year-old brother, one sponsor took 4-year-old me. And that’s really where my memories begin howling and screaming as I’m being taken away. And that was being done for our own good, to give my parents time to recover and get on their feet. But of course, when you’re four, you don’t understand these complexities. And so, that, I think, has always imprinted itself on me. That memory of being forcibly removed. Which is an experience, I think unfortunately rather common in this world of refugees and displacements.

Georgina Godwin:

Now, you were too very much loved, very much wanted children. But before you came along, your parents had adopted a girl. She was left behind. Why was that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

This was 1975, and our hometown was the first town captured in the final communist invasion. My father was in Saigon on business. My mother had to make a life and death decision. She decided that she was going to flee with my brother and myself, and leave behind our oldest adopted sister who was about 16, I believe. And she was going to be in charge of guarding the family property and with the assumption that we would come back. Which I think my mother made a good faith assumption because she’d never intended to abandon the country or her daughter.

But of course, we didn’t come back for quite a long time. My parents wouldn’t see her again for 20 years. I wouldn’t see her for 28 years. And by then I had forgotten who she was. I think the first time I even recalled as a person with a memory that I had the sister when a letter showed up in the mail when I was 10 or 11, and there was a photo of a young woman in it. 20-something years old, beautiful woman. And I had no idea who she was. And I was told, “This is your sister, [inaudible 00:06:09].” And this was my first sense that… This was not my first sense, but this was the very vivid reminder that we had ghosts in the house, people we had left behind, an absent presence. And I think I would be haunted by that absent presence of my adopted sister for many years.

Georgina Godwin:

And so, many things that you just didn’t talk about within your family. I mean, there was a murther over a lot of that wasn’t there?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yes, and I don’t think we were unique. I think there are a lot of families who have survived trauma and historical difficulties, and so on, where the older generation does not want to or cannot speak about the past. It’s not a uniquely Vietnamese or refugee experience, but it’s very common in Vietnamese refugee experience. Also, common in the world of war survivors. And so, sometimes memories are transmitted explicitly. But sometimes I think the past is transmitted through silence, through absence, through these emotional vibrations and ghosts that are in the house that are never spoken of, but of which we are still aware.

Georgina Godwin:

I mean, you have this wonderful line. You say it’s the writer’s dilemma to be scarred enough to be a good writer, but not so scarred as to be truly fucked up.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, you said the word, not me. But I wrote it. Yeah, I think that’s true. I mean, I think I’ve been a fairly functional human being, but I might be deluding myself. When I started going out dating my future wife, I told her, “I think I’m pretty normal.” And she said, “No, you’re not.” She proved she turned out to be correct, but she’s worked on me. So, I think I’m functional at this point.

Georgina Godwin:

There’s a wonderful movie theme going through all of this. You talk about who might play your parents in the movies of their lives, how those movies will never be made. Although actually, your last book is about to be on television. And you reference, of course, that whole genre of war movies that were made after Vietnam. Before we talk about those specifically, I just want to talk about something else you mentioned in terms of movies, and propaganda, and Westerns, and how really this was the United States justifying genocide.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, absolutely. I grew up watching American Westerns and American War movies. And I was rooting for the Americans against the Cowboys or against whoever Americans were fighting. And of course, these were the movies that the United States was projecting all over the world. So, American soft power was very important to the projection of American hard power. And I was so persuaded by watching these movies that I’d never thought twice about what was actually happening in them. So, just to speak about the Westerns, for example. Yes. I mean, genocide was committed in the making of the United States. And that’s simply a fact that I think most Americans have not really dealt with.

I mean, conceptually, yes, but the details, the details are horrific once you start reading about what took place. But all you get in these Westerns is this fantasy of heroic conquest and settlement so powerful, that other countries have adopted the American Western. So, I remember going to a children’s park in Paris a few years ago with my children. And there was a ride that was made out of canoes and teepees with drawings of Native Americans from the 19th century reenacting this fantasy that the United States created.

Georgina Godwin:

And I mean, every child has played Cowboys and Indians, haven’t they?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, absolutely.

Georgina Godwin:

It’s extraordinary. Onto the war movies themselves or the Vietnam War movies themselves. Firstly, there’s a wonderful coincidence in terms of the music from Apocalypse Now, which is The Doors, lead singer, of course, Jim Morrison. You’ve got a wonderful fact about his dad and your book.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yes, it was quite surprising to discover that his father was an admiral in the United States Navy. I don’t know exactly what he thought about his son becoming the singer for The Doors. But the father was actually in charge of the American naval evacuation of Saigon.

Georgina Godwin:

And that movie that we’re referring to, it’s Apocalypse Now. Again, you ask, are you the Americans killing the Vietnamese or are you being killed? I mean, how do you even begin to unpack that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I can’t. Well, it took me decades. And yes, I mean, I think the power of movies is such that we’re seduced into identification. And for me, watching a movie like Apocalypse Now and many others, like it was to see myself as an American until the Americans started killing the Vietnamese. And it split me in two.

Georgina Godwin:

Yeah. I mean, you were talking about trauma living on in families. But it also lives on through populations. You talk about Koreans repeating what was done to them by the Japanese, who in turn, imitate the white colonizers. How atrocity just repeats.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think that is, for me, it seems like a truth and unfortunate truth, and a truth that we cannot get away from. Because I think it’s a very human impulse to separate the human and the inhuman to project inhumanity onto our enemies, onto our others, reserve humanity for ourselves, which only allows us to do inhuman things to those people we consider to be inhuman. And when we’re victimized, it doesn’t necessarily turn us into better human beings. And so, that’s where you see this unfortunate irony of history where victims can become victimizers in another generation.

Georgina Godwin:

And you also talk about the evolving nature of who the victims are within the United States. So, for instance, the Irish become white. They don’t start off that way.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, no, absolutely not. I mean, well, obviously Irish were already subjugated in this context in which we’re speaking. But when they came to the United States, they were similarly subjugated. The popular depictions of the Irish and cartoons, for example, was highly racialized. They were considered to be Black or nearly Black. And it took many, many decades for the Irish to become white. And partly the way that they did it was through not being Black, not being Chinese, for example. The Irish were building one half of the Transcontinental Railroad while the Chinese were building the other half. And being able to distinguish themselves from people who were increasingly racialized would make the Irish less white as the decades progressed.

Georgina Godwin:

How was that racial experience for you growing up in terms of actually confronting it in your day-to-day life?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I think I internalize much of the racism. I think that’s a very common experience too. So, I grew up in a very multicultural city, San Jose, California. But I went to a very white high school with a handful of Asians. And we knew we were different, we just didn’t know how. So, we would gather every day in a corner of the campus for lunch, and we would call ourselves the Asian Invasion, which the only language we had for ourselves. And of course the irony is that Asians never invaded the United States. It’s been the United States that has invaded Asia. And so, that was just the first sign of this internalization of racism. But I also internalized racism directed against other populations in the United States. And it’s been a decades-long process to become aware of that internalization, to become aware of the histories of racism in the US, and to continue to uncover those histories for myself.

Georgina Godwin:

I love the structure of the book and the way it’s written. America is America in Capital Letters, trademarks. Trump is never named. He’s just a black void. And then a lot of it is written in the second person. Just explain that, the choice to write it in that way.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Honestly, it was very intuitive and it was very playful. So, one of the lessons I’ve learned from being a father is that reading children’s literature, children’s authors can do whatever they want. They have no rules. As long as they entertain their young readers, everything will be accepted. I think adults have grown up and we’ve internalized all kinds of rules. And I wanted to shrug a lot of those rules off. So, Trump’s name is redacted because in fact, redaction is a part of the American experience. We’ve redacted all kinds of censored documents to prevent ourselves from thinking about what our country has done. Whenever we say America, it comes with a huge amount of mythology that Americans have a very hard time acknowledging. So, to put it in capital letters and trademark is meant to make Americans think twice about this word that they take for granted.

Georgina Godwin:

Absolutely. And then you examine Vietnam. You go back to Vietnam. What was that like for you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I grew up as an American, and I wanted to be an American very, very badly. But I also was aware that I had a deep connection to Vietnam. So, at a certain point, I decided I had to go back. I had to see the country. And I started going back in 2002 until 2014. And went several times for at least a year’s total. And I went back without the expectation of thinking that I would become 100% Vietnamese if I went, because I don’t really believe in that notion of authenticity. But I did want to see the country, how would it change? What the people were like? How did I fit in or not fit in? And just to give you an example, I came back and my Vietnamese was so good that people would say to me, “Your Vietnamese is great for a Korean.” That’s how I was perceived, I think.

Georgina Godwin:

Yeah. I was really interested to read about the temple of literature in Vietnam and the fact that censorship is still so bad. I mean, you could not really publish there.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Literature has been very important to the history of Vietnam where I think it’s a very literary country, literary people. And of course there’s a temple of literature because at a certain point, throughout much of Vietnamese history, you had to be an expert in literature in order to be considered a ruler, to be part of the ruling class. But now the country has changed. It’s a very capitalist country. I think literature has fallen by the wayside to some extent. And when it remains important, it’s censored. Its authors are easily put into jail for expressing any opinion that is contradictory to what the government wants.

In my case, because I publish in English, it’s a different issue. It’s a matter of translation. And so, we’ve had a translation of The Sympathizer, for example, since about 2016 in Vietnamese, but my publisher can’t get it published. The government also would not allow our TV series to be filmed in Vietnam. The TV series won’t be allowed to be aired in Vietnam. So, there’s still some very, very sensitive topics, political topics in the country, economic topics. And unfortunately, I’m a provocative person, so I like to go exactly where I’m not supposed to speak.

Georgina Godwin:

Yeah, absolutely. And when you’re speaking, you’re speaking in English and you write, I just love this line, you talk about how the more fluent you became, the further it carried you from your parents. And you also talked about what a big place the library had in your life and that your parents didn’t realize that actually you’ve been kidnapped by books. What a wonderful concept.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yes, and I think that’s a very powerful concept. It speaks to how much power literature exerted over me as a safe space in some ways to rescue me from this refugee world that I could see my parents were struggling in. And that was affecting me. And it was a painful thing, I think, my relationship to literature, how it saved me in some ways. But also took me away from my parents, alienated me from them because it gave me a completely different language and culture than what my parents had. And so, I’ve come to the conclusion that the irony is that literature is a safe space, but it’s also a dangerous space. It’s a space where I can realize there’s power in stories for both salvation and destruction. And it’s important to recognize that power. And I think it really exists. I’m not overestimating. This is why in the United States there’s campaigns to ban books. People wouldn’t want to ban books if books weren’t actually powerful.

Georgina Godwin:

For you in terms of, because you’ve always been a reader and you knew you wanted to be a writer from very early on. And you quote many, many works in here. I was really interested to see that Invisible Man came up and clearly something that really meant something to you. The Atlantic’s just released its top 137, I think it was, great in American novels. Invisible Man on there too. Why is that book so powerful?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

It resonated with me really deeply when I read it in college. I had not read very many Black writers up until that point, until I took a whole course on Black literature at Berkeley. And I think it’s booked me very powerfully because it’s an allegorical novel. I mean, it’s very definitely about Black experience. But the allegory being invisible and hypervisible at the same time, I think, speaks to a lot of so-called minorities because that’s exactly the position we occupy. We’re not seen until we’re trouble, and then we’re seen way too much. And so, I took a lot from Ralph Ellison’s novel. He also said that he had dilated realism in order to deal with the almost surreal quality of everyday life for Black people in the United States. And I felt that there was some of that surrealism involved for me being a Vietnamese in the United States as well.

Georgina Godwin:

And you called your son Ellison.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

And I called my son Ellison. And Ralph Ellison is named after Ralph Waldo Emerson. And he’s Ralph Waldo Ellison. My son is Ellison. So, there’s a whole unfair genealogy I’m putting on the shoulders of my son. I don’t know how he’s going to react to it.

Georgina Godwin:

Well, but that is something that you bring up because you talk about passing on trauma.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yes. I think that being a refugee has given me the emotional damage necessary to become a writer. And I’ve tried to pass a little bit onto my son, not enough to hamper him, but to make him more empathetic, make him aware of where his privileges come from, that he wouldn’t be living this charmed American life that he is if it wasn’t for his grandparents and what they’ve been through.

Georgina Godwin:

And I mean, you also point out that soldiers, for instance, get PTSD. It’s recognized. They might get a government payout, they get medicalized. Refugees have to deal with that trauma by themselves. It’s a secret shame.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, yes, because soldiers are at least elevated and lionised, even if hypocritically by their societies. And they get the recognition, and the glamour, and the glory, whatever that means, and whatever that’s worth. Refugees for the most part, do not get any of that. They’re only treated as objects of fear, as we’ve discussed. And their stories are not even recognized as war stories. They’re just treated as tragedies or civilian stories. And the Vietnam War, I think, was hardly unique in that the majority of people who died were civilians, not soldiers. And the overwhelming majority were Southeast Asians, not Americans. And yet their legacies or stories are invisible except to their own community. And so, I think there’s a deep fear in the older generations that their experiences will not be heard. Certainly not be heard by larger society if they happen to be displaced, but also by their own children and grandchildren. And that leads to a lot of frustration, and ambivalence, and melancholy.

Georgina Godwin:

You write about who you are writing for. And I love the way that the book is completely uncompromising in terms of there are no translations. You can work out what it means if you can’t, whatever. And I really like that. Who is your audience?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I just remember growing up in the library reading books, there would be French, there would be Latin, there would be no translations. And it would just be assume if you were an educated person of the Western world, you would know these things or you would find out. And if you didn’t, your shame, not the writer’s shame. And so, I appropriated that sensibility. I want to write from that position where everybody can come to me because I think they can, if they were willing to just make a little bit of effort. So, I write first and foremost for myself, and then I write for my wife, and then I write for my fellow Vietnamese and Asian-Americans, and I write for Americans, and I write for you, and I write for the rest of the world.

Georgina Godwin:

Writing is hard, we know that. But you’ve also described writing as just some of the most fun things that you’ve ever done, that you’ve had a brilliant time.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah, I’m a masochist. So, I’ve inherited this from my very Catholic parents, a sense of suffering, sacrifice, martyrdom. I’ve translated that into writing as a form of experiencing all those things. And most of the time it’s painful, and it’s drudgery, and it’s labor, and it’s self-lagulation. And then you have these bursts of ecstasy. And for me, that’s very rare usually. But The Sympathizer, my first novel, that was really two years of almost sustained ecstasy and writing. It was my best writing experience ever.

Georgina Godwin:

Wonderful. This horrible phrase, giving voice to the voiceless, which is something that’s often, I think, applied to you. As you point out, Arundhati Roy says that there’s no such thing as voiceless. They’ve been deliberately silenced. And I wondered if you’d just talk to us about that. I mean, Vietnamese as everybody is mostly, are noisy.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, yeah, absolutely noisy. Have you’ve ever been to a Vietnamese house or restaurant, and so on. But of course, we’re silenced in the larger sphere of things outside of Vietnam. And even in Vietnam, there are many silenced Vietnamese people. The idea of giving voice to the voiceless, I think makes people who are hearing these voices feel better. We know there are all these silenced or voiceless populations. We don’t know their experiences. If we can just have someone speak for them so we can understand them, that’s what makes people feel better. So, we elevate these voices for the voiceless, and the temptation is not to do anything to actually alleviate the conditions of voicelessness, which are much more complicated, political, economic, historical, and so on. So, I think literature is a stopgap measure in some ways. It can provide us with a feeling, a pleasurable feeling of empathy, and then it can relieve us of the need to take any action.

Georgina Godwin:

And I mean, you’ve been taking action for years. You were radicalized at college. One of the first things you wrote was this very critical review of Miss Saigon. And you went back 30 years later to look at it again. Why is that such a problematic piece of musical theatre?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

It did originate in London, I think. Well, I mean, it was controversial back in the 1990s. And the story at the core is still itself deeply problematic about an American soldier who rescues a Vietnamese sex worker, impregnates her, takes her baby away to the United States, and then she commits suicide as a reenactment of Madame Butterfly. That’s a very classic orientalist story that white people seem to love for some reason. But as David Henry Wong satirized in his play, M Butterfly, is totally ludicrous if you simply reverse it. And in his story, what happens if a beautiful blonde Kennedy married a short Japanese businessman, and then was abandoned by him, and then committed suicide? We would think that’s a ludicrous story. But that’s essentially what has taken place.

Georgina Godwin:

The hero in your story is of course, your mother. You say she’s a hero, but she’s also quotidion and it’s an ordinary life. But you lead us to this woman. You introduced us to this woman who loved her children so deeply, but couldn’t say it. And the last 13 years of her life, which was heartbreaking for you and misremembered you, you talk about this a lot, about how you don’t remember things, how your journals of the time don’t reflect what your memories are. Just unpack that a little for us.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah, I mean, she was a heroic woman. She was a very successful businesswoman. And yet at the same time, she also went to mental facilities three times in her life. And the first time was when I was four or five, so I don’t remember. The second time I wrote about it in college, actually, in a nonfiction writing class. Such a painful experience that I put the essay away for 30 years and didn’t look at it again.

I remembered enough to think that, to know that my mother had gone to this mental facility, I’d been there to witness it. And in my memory, I was a little boy when it took place. During the pandemic, I looked at that essay again and realized I had written 10 pages about how that happened when I was 18. And I wrote about it when I was 19. And so, my memory distorted everything, even as a fully capable young adult. And so, that was one of the signs for me that this was a story that I needed to revisit, to unpack, to see why this had happened to my mother and why it has such an impact on me.

Georgina Godwin:

You also query yourself a lot. You wonder if this is a betrayal of your mother, if your mother would’ve liked this, that if she’d been unhappy, that you were, as you put it, telling on her.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah. I think any memoirist who does not worry about betraying people is probably a problematic person. I’m a reluctant memoirist. And I think anybody who’s an enthusiastic memoirist should scare us. But to tell the truth about a very intimate situation, I think oftentimes implies or requires betrayal because you’re betraying someone else’s secrets, not just my own. And I think I really could only write this book after my mother passed away in 2018. And I do think of this book as a complicated act of love that also involves a betrayal of confidence.

Georgina Godwin:

You won the Pulitzer Prize. Now you are in fact, on the Pulitzer board, the first, as we said, at the top Asian American to be. So, you’ve been invited to join all sorts of clubs that were previously the preserve of just the white male Americans. Is that something you accept?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I’ve only accepted those things out of curiosity. As a writer, I’m very curious about people and also about the way that societies and power operates. I just wanted to see it for myself. Which is the same impulse brought me to go see Miss Saigon in person as a student, which cost me a lot of money for my budget at the time. And then I saw it and I was like, I guess I didn’t need to see it. It confirmed everything that I suspected. So, I’ve been to a few of these clubs. I’ve met a few billionaires and so on. And honestly, I don’t think I need to meet anymore or see anymore. I don’t think I’ve learned anything new about human nature that I didn’t already suspect.

Georgina Godwin:

Finally, of course, we’re right in the middle of a horrible global crisis. America looks frankly tanked for the next few years, Ukraine, but Palestine. And that’s something you’ve been very vocal on.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Absolutely. What can I say? It’s a deeply controversial issue in the United States for obvious reasons. But I find it hard to look at the situation in Palestine, what I would consider to be Israel’s war on Gaza, and not think that what we’re witnessing is, at the very least, a massacre, and an ethnic cleansing, and very, very arguably genocide, which is how I perceive it. And the reason why I’m vocal about it is because the United States is Israel’s main supporter, literally giving billions of dollars, literally providing the bombs that are being dropped on innocent people. So, it feels to me a matter of conscience to speak out.

Georgina Godwin:

You’re on this intense book tour at the moment. But what comes next?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I will be at Al Jazeera next to record an interview with the filmmaker, Raoul Peck, who I’m a huge admirer of. He’s the director of I’m Not Your Negro and Exterminate All the Brutes. He’s an amazing filmmaker. And I think we’re very simpatico on political and artistic levels.

Georgina Godwin:

And in terms of writing?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, in terms of writing, I’m sorry. Yes. I will be writing the third and final novel of The Sympathizer Trilogy very soon.

Georgina Godwin:

It’s just been such a pleasure to speak to you, Viet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Thank you so much.

Georgina Godwin:

A man of two faces, a memoir, a history, a memorial is published by Grove Press in the US and Corsair here in Britain. And it’s out now. You’ve been listening to Meet the Writers. Thanks also to our producer, Tamsyn Howard. And you can download this show and previous episodes from our website or wherever you get your podcasts. I’m Georgina Godwin. Thank you for listening.