Pulitzer Prize-winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen joins us to discuss his new memoir, A Man of Two Faces, which tells the story of his childhood in Vietnam, his time as a refugee, and his experience coming to America, including the harrowing story of how his parents were attacked by a gunman while working for WNYC

Link here for the Podcast episode

Transcript below:

Alison: This is All Of It on WNYC. I’m Alison Stewart, live from the WNYC Studios. Thank you for sharing part of your day with us. Before author Viet Thanh Nguyen won the Pulitzer Prize in literature for his novel The Sympathizer, before he attended UC Berkeley, and before he was a kid growing up in San Jose, he experienced a life-altering and dramatic event. He, his older brother, and his parents fled Vietnam during the war. They left behind their property, their extended family and Viet’s older adopted sister who was 16 at the time. Viet was just four years old.

After a period in a refugee detention center in the US and some months in the home of American sponsor, but separated from his parents and his brother, Viet and his family finally settled in San Jose. Though Viet and his family have escaped the violence of the war, they faced new norms of terror and new forms of terror in California from racism and prejudice to scary incidents of gun violence. Viet’s Bama worked hard to provide for their children. They opened a local grocery store where they worked every day of the week.

As he grows older, something of a distance grows between Viet and his parents. He learns English, reading anything he can get his hands on. The library becomes his special place. He writes in the second person in his new memoir referring to himself as you. You borrow a backpack full of books every week and read them all totally absorbed. The more fluent you become, the further away from Bama the language carries you. Decades later, it occurs to you that this might have been what you wanted. As much as you yearn to be closer to Bama, they work too much, have so little to say to you.

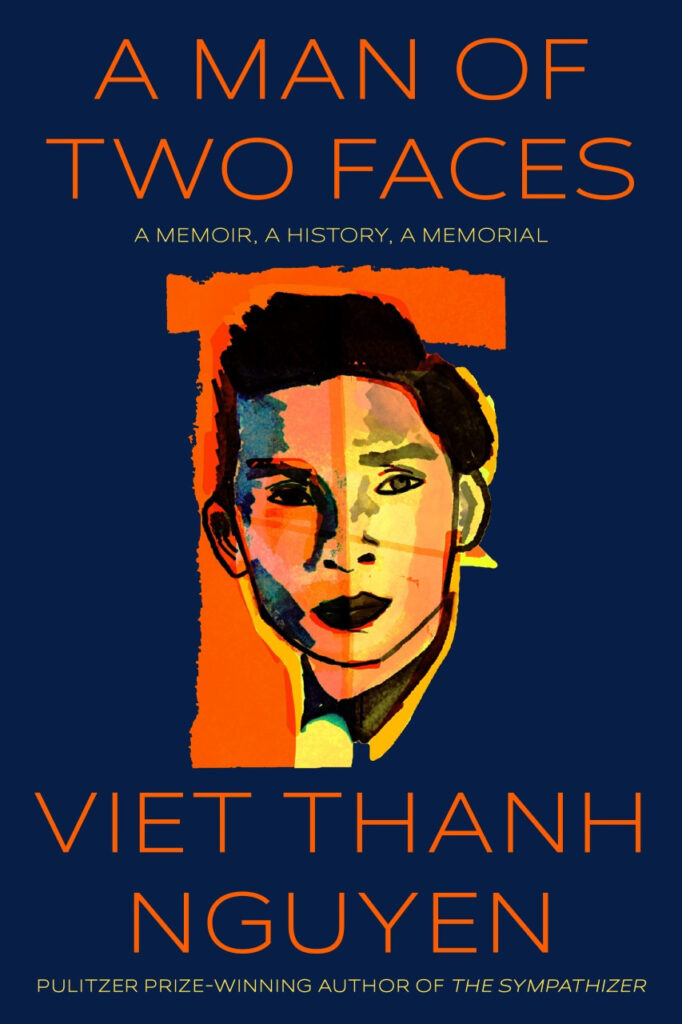

They turn you over to the care of the library, but you not realize how the library will steal you from them. By the time they do, you have been kidnapped by literature, by books, by English. Viet begins to see himself as a split between his Vietnamese heritage and his new home in America as evidenced by the title of his new memoir, A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial. Viet Thanh Nguyen will be speaking tomorrow night at the 92nd Street Y in conversation with Min Jin Lee. That is at 8:00 PM, but first, he joins me at the WNYC Studio. Thank you for coming in.

Viet: Alison, such a pleasure to be here with you.

Alison: How did you know you’re at a place in your life when you could write this memoir, which is very candid?

Viet: Yes, it was a real struggle to come to that decision, but I’d written a couple of novels and some other books as well. One of the things that I discovered in writing fiction is that I had to excavate myself to find the emotions that I could put into my characters. The more I did that, the more I realized that there were places inside of me that were really terrifying, places that I had sealed off for so many decades in order to survive the refugee experience and growing up in the United States. My mother passed away in 2018, and so that really was then the trigger for me to finally make that decision to look more deeply within our history and myself.

Alison: You write about your complex feelings about writing this and writing about your mom in particular, how, you just mentioned, passed away. Would you read that passage for us on page 321?

Viet: Sure. I am ma’s descendant. What does it mean to write my mother’s obituary, my mother’s story, to claim dissent from her, especially since ma would not want me to write about her this way? Not that she ever forbade me. She trusted me, whose books she never read, but was proud of anyway. Since she never consented to the story written in a language she had difficulty reading, am I betraying her? If I do betray her, can I be loyal at the same time? Her life is epic, and yet quotidian, deserving to be told and known according to me, if not her.

Her story matters because she is ma, but it also carries weight because it resembles those of many other Vietnamese refugees. Heroic as she is to me, perhaps ma is not exceptional to anyone but those who love her, but saying my mother may be more typical than exceptional is no loss. When I hear stories of other refugees and what they survived or not, I am immediately captured by their gravity. Not the same as ma’s, but similar. Not exceptional, but common. Not stereotype, but history. Each one deserving a story, each one with potential to be portrayed and perhaps betrayed.

I wrote about ma because I believe stories matter, but if stories can dismember as much as save, what does my version inflict on her? If I remembered everything about ma and wrote it down, is it betrayal?

Alison: That was Viet Thanh Nguyen reading from A Man of Two Faces. Gosh, what did you see as your responsibility to your family, to your family’s memory, to the history of your family, but then also as a writer, as someone who’s putting this out and asking people to read it and spend money on a hardcover book?

Viet: Right. No, absolutely. I think that the obligation is always to the truth of the experience, but also to the beauty of it. When I look at my mother’s life and the life of my father, and all these Vietnamese refugees, they’ve endured so much. There’s this huge multiplicity of stories, thousands of stories, and I wanted to tell one story, my mother’s, but with a feeling that it also represented so many other Vietnamese refugee experiences as well. That was why I thought it was important, why I thought it was worth risking this act of betrayal and loyalty that this book is at the same time.

Alison: Why did you choose to write in the second person addressing you?

Viet: I found it very hard to write about myself. I spent my life telling myself, “I’ve had a very boring life. It’s my parents who’ve had the really dramatic, epic, movie life.” In fact, part of the point of writing a memoir for anybody, I think, is to realize that your story matters, your emotions, what you’ve been through, what you’ve suppressed, how you’ve deceived yourself, all these things really do matter. In order for me to tell that story, I had to gain a little bit of distance from myself, and so yes, much of the book is written about me talking to myself, as I interrogate me.

Alison: What was a story that you had always been telling about yourself or your family that you realized after writing this book, it wasn’t really true or it didn’t really happen that way?

Viet: Well, when I was in college, I wrote an essay about my mother and her commitment to a psychiatric facility. I put that essay away because obviously, it was very difficult for me to write for 30 years, not wanting to think about that experience. For 30 years, I told myself my mother had gone to the psychiatric facility when I was a little boy because that’s how I felt, terrified, and childlike. Then during the pandemic, I opened up my archive, looked at that essay and realized I had written that essay a year after my mother had gone to that psychiatric facility when I was 18.

Even as a young adult and as an adult, my memory had completely deceived me without me realizing it. I don’t think that’s uncommon. The book is also about self-deception, and about the changing nature of memory, and about our very unreliable grasp of our own selves and our facts.

Alison: Why do you think your memory is so different from the diary entry that you had about this?

Viet: I think that I’ve changed. I’m thinking that after I’m done with touring with this book, I’m going to burn my diaries because I wrote those when I was 17 to 19 or 20. Every time I look back on those diaries, I’m so embarrassed by myself. I’m so embarrassed by the person I was. I’m terrified of that person because when I go and I look at those diary entries, part of what I’m talking about, in addition to all the usual adolescent angst, is about why I can’t feel anything. Why can’t I say I love you to my parents, but also to my girlfriend at the time? Why do I feel so numb? Why am I so awful of a person?

I think that I’ve been on a lifelong journey of finding my capacity to love my wife, my children, my family, and then realizing that I think the refugee experience and watching what happened to my parents, and the terror of it all, made me shut down emotionally. This book is also about going back to uncovering what the refugee experience did to someone like me, who I thought was completely normal, but as my wife has told me often, is not.

Alison: There’s a refrain that repeats, “This is a war story.” Why do you want to remind the reader of this periodically?

Viet: I think that Americans and possibly people in many different countries when they think of war think of battles, guns, tanks, soldiers, and so on. Very dramatic stories. I agree with that, but I grew up in a Vietnamese refugee community full of civilians who had been totally traumatized by war. I saw the effects of war every time this community gathered or when people would tell me stories. I realized that for many civilians who have lived through war time, they’ve experienced more terror and more horror than a lot of soldiers did.

A lot of soldiers don’t actually see combat. They sit on a ship or guard a boat or guard a base or something like that, but if you talk to Southeast Asian refugees or any refugee who’s made it to this country, everybody has a horrifying story. They’ve become refugees because of war. That’s why I insist that these civilian stories, the stories of women and children are also war stories as well.

Alison: What was your brother– he’s older than you, a good deal older than you. What was he able to provide you? What information that was useful for you as you started to write this story?

Viet: My brother’s always been there for me, so I’m grateful and love him so much. He’s been so supportive, and one thing that the memoir talks about is the fact that when we fled from our town in 1975, our town was the first one captured in the final invasion by the North. My mother made this crucial decision to leave with my brother and myself, but to leave behind our adopted sister who’s 16 to guard the family property and the house from the victorious communist. Of course, she couldn’t do that, and so can you imagine being 16 years old left by yourself in this horrifying situation?

When I was younger, when I was in college, a so-called friend said, “Yes, there’s a rumor that you are adopted.” I told my father, and he was so upset. He said, “No, no, no. you are my son and I’m going to take a DNA test if you want me to.” My brother pulled me aside later and he said, “You know why we know you’re not adopted? Because mom didn’t leave you behind.” That’s a brutal fact of the family history, and he was a witness to that as well.

Alison: My guess is, Viet Thanh Nguyen, the name of the memoir is A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial. It’s interesting the way the book is written, there’s all sorts of different choices with font. Sometimes the font is very big when you’re trying to make a point. There’s one page I remember that’s I think it’s almost diamond-shaped and it slurs. Were these, in your mind as you were writing, did this come after the manuscript was done and you realized you needed to have different emphasis because some parts of it almost feel like poetry?

Viet: I wrote the book out of instinct. There was no plan, I just followed my impulses. One thing that’s happened to me is I’ve become a father, which totally caught me by surprise. I never wanted to be a father, but I’ve turned out to really love the experience and love my children. One thing my children show me is that there are no rules. There are no boundaries, there are no conventions when you’re a little person, and you learn those things as an adult, sometimes for the better and sometimes for the worse. I’ve read a lot of children’s literature through them, and in children’s literature and in poetry, the writers can do whatever they want, and they have a lot of fun.

That’s actually the impulse behind those things that you pointed out. I was having fun, and it was so important to have fun writing this book because a lot of the stories are actually quite sad and very serious. Yet, at the same time, I’m also trying to find the humor and the jokes and the ways that we survive psychologically and being playful on the page, but also in life is one of the ways that we survive terrible things.

Alison: Your parents had a convenience store in San Jose, and they worked seven days a week. What do you remember about the store? What did it smell like? What was the light like in the store?

Viet: Yes, it was a store in Downtown San Jose, and in Downtown San Jose in the ’70s and ’80s, no one wanted to be there. The Vietnamese refugees came in and they started revitalizing it through places like this store, the Sàigòn Mới. To me, it was just a little grocery store that smelled of jasmine rice because we had 50-pound sacks of rice stacked to the ceiling and had all these interesting odors, like spices that I didn’t understand. There were yellow strips of fly paper dangling from the ceiling, studded with flies.

The only language you heard in the store was Vietnamese because only Vietnamese people would shop at this store. The store was really an anchor of the Vietnamese refugee community. So many people from that time they have come up to me and said, “Yes, we shop there. That’s where we went to get our goods.” That’s how they reminded themselves of home by being able to cook the food that they knew. That’s what my parents were supplying, and I was fortunate that I didn’t have the stereotypical shopkeeper child’s story, which is that my parents actually didn’t make me work there very often.

I worked there enough so that I didn’t realize I don’t want to be here. Their ambition was for my brother and I to go to school, get an education, and do something else besides being shopkeepers, which is how they sacrificed themselves for us and for everyone else in Vietnam that they were sending money home to.

Alison: If you look back and you think about it, honestly, aside from not wanting to do work, did you want to be in the store?

Viet: No, no, I didn’t want to be in the store. I mean, the store to me was this alien space because I was growing up as an American. I was eating American food. I was watching Leave It to Beaver, and I was like, “Oh, yes, people eat mashed potatoes and roast beef or whatever at home.” Then you go to the store and it is all of to this little boy, all these alien things that Americans didn’t eat and didn’t buy. To me, it was a place of arduous sacrifice and strangeness. It was the place that was kidnapping my parents away from me because they were working there out of love for their family, but ironically that meant they couldn’t spend time with me, and so it was a very sad space for me.

Alison: But you found a happy space, the library. What opened up for you when you suddenly realized, “Oh, the library’s where I’m going to find myself?”

Viet: I don’t even know how I came into English, but it was as if English was my native tongue, even though it wasn’t. I just, all of a sudden, knew how to read and write and speak in English, and I gravitated to the library where there was just enormous numbers of stories. No one was there to stop me from reading anything I wanted, which was great.

Alison: [laughs] Oh, no, that opens up a couple of questions.

Viet: I also started to read things I should not have read because there’s nobody telling me I can’t go into the adult section and read Philip Roth or go into the how to section and read sex manuals, which were there in the library for example. My parents would’ve been shocked at what I was reading. All of that made me into a writer because it saved me, the experience of being able to escape every single hour of the day when I wasn’t in school through books.

Alison: Was there anything that you read that you found yourself or a style you found yourself parroting-

Viet: Parroting?

Alison: -of a language? I’m curious.

Viet: I grew up just infatuated with English literature from England. I was an Anglophile, I was like a Vietnamese refugee boy growing up in provincial San Jose and reading Shelley, Byron, Thackery, Dickens, Austen, and so on. I was trying to mimic all those because I was like, I want to be a writer and the Anglophilia tradition was the only thing that I knew. I also mentioned Philip Roth, and again, I read Portnoy’s Complaint when I was like 12 or 13. Honestly, the only thing I remembered for decades was that the character of Alex Portnoy, who was this very horny adolescent, masturbated with everything including a slab of liver from the family fridge.

I thought, “Gross, who eats liver? But we did.” Then he masturbates with that slab of liver, and then he puts it back in the fridge and then the family eats it for dinner later that night. How can you forget a scene like that? When I wrote my novel, The Sympathizer, it just popped into my memory and there’s an homage, let’s just say to Philip Roth in that book.

Alison: Oh my God. I asked because I remember I went to college with a brilliant man, young man who’s a brilliant oncologist in New York now, I won’t say his name. He was a refugee and he would always say, “Buddy, buddy.” He told us that he learned to speak English watching cartoons. He had a certain inflection on certain things, and that was who he spent his time with while his parents were working so hard so he could become an oncologist and save people’s lives. My guest is Viet Thanh Nguyen, the name of the book is A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial.

As if it weren’t dramatic and interesting enough your family story, there are two times when your family faced gun violence. One of them is wild, a man, he knocks on your door, as I remember, and you answered the door, and he’s got a gun. Your mom sees a moment and runs out into the street almost, I don’t know if you’re distracted or to escape, and he follows and your dad locks the door. When you think back to that moment, what stands out to you the most?

Viet: It was a shocking moment, obviously. I was 16 and my mom had always told me, my parents had always told me, never open the door because home invasions were a thing in San Jose, and we pioneered it. The Vietnamese gangsters were the ones who were invading people’s homes at gunpoint, but the guy who knocked on the door was a white man. I think that made my mother trust him for some reason, she opened the door. What I remember is my mother saved our lives was because when that guy came in and pointed the gun at us and said, “Get on your knees,” my father and I obeyed, we were the men of the house, but we obeyed.

My mother just, I don’t know where she found the courage or the will but she dashed right by him, and we were all very lucky he didn’t pull the trigger. That saved our lives, and so much of the book is about my mother saving our lives by the decision she made in such difficult circumstances, not just here but in other times as well. It’s about the heroism that gets unrecognized because I think to people who didn’t know her she was an Asian woman who didn’t speak good English, but to me, she was a hero.

Alison: Somebody’s actually texted in a question, if it’s okay if I ask, someone wants to know, I see it on the corner of my eye. Excuse me with my glasses on. Please ask what happened to the sister that was left behind.

Viet: She was 16 and she was sent to a so-called voluntary youth brigade. This happened to a lot of people who were Catholics around the losing side of that war. Then I didn’t even know I had an adopted sister because I saw her when I was four. I obviously knew she was but then I didn’t remember. When I was around 10 or 11, this letter shows up, and there’s a photo in there of this beautiful young woman at that time in black and white, and I was told, “This is your adopted sister.”

I grew up then from that point onwards aware of this absent presence in our house that this ghostly haunting. My parents would send her money to take care of her and other aunts and uncles and so on. She would get married, she would have kids. I didn’t come home to go back to Vietnam for 27 years.

Alison: Wow.

Viet: We finally met when I was going to my 30s but we had to rendezvous, not in our hometown because my father said, “You can never go back to our hometown, Buon Ma Thuot.” We had to go meet in a beach town and she showed and you have to understand I come from a family of devout Catholics who don’t know how to have fun. She shows up and she’s in makeup and she’s dressed spectacularly in leopard print and she’s young and stylish. It’s like, “Yes, she’s adopted, she’s not biologically related but she is my sister and she survived.”

She remembered she knew how to enjoy herself to be beautiful and that’s what I’d like to take away from that part of her history.

Alison: We know so much more about generational trauma now than we did 5 years ago or even 10 years ago. When you think about generational trauma, has it influenced your life? Do you think this applies to you and your family story?

Viet: I think that my parents and certainly my mother were traumatized. Part of that, what I try to think through in this book is, how do we know what happens to people is happening because of something inside of them, inherent to them, maybe she was already prone to psychiatric breakdown or was it history and everything she’d been through war, famine, colonization, hammering on her? I don’t claim to be a victim of trauma but I am an eyewitness to it. I think so many children and grandchildren of refugees but also, war veterans are eyewitnesses to their parents’ trauma, whether that trauma is spoken or not spoken.

I’ve talked to so many people who said, “Yes, it wasn’t as if mom and dad talked about the war, whatever that was for them. It was often they didn’t talk about it.” There’s this huge silence, this absence but the absence itself would shape our emotional responses. I think of history as rippling through us emotionally and that’s how we know history exists, is because it’s become embedded in how we behave and how we act and so many– When you hear the stories of your parents and grandparents oftentimes it is traumatic what they tell, my mother told a story.

I didn’t even ask her, I was plucking hairs from her head when I was 10 or something and she said, “I saw a dead body on a doorstep,” when she was a little girl younger than me because a famine killed a million people in her region. That’s horrifying and that story then becomes embedded in my mind. It’s not trauma for me but it is the effect of trauma continuing in a secondhand manner throughout my generation.

Alison: My guest Viet Thanh Nguyen, the name of the memoir is A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial. Just to remind you, he’s speaking tomorrow night at the 92nd Street Y at 8:00 PM with Min Jin Lee. There’s a section you write, “You speak out because apparently, you are good at giving voice to previously voiceless.” As the New York Times described, The Sympathizer, “Dear reader, have you ever been to a Vietnamese restaurant, wedding, bank or family gathering? If not, you’re lost. If so, you know, this gigantic fun. By the way, if so, you know that Vietnamese people are not voiceless, they are really, really loud.”

Viet: It seemed necessary to make that point because that– I think so many so-called minority writers and writers of color or writers from countries that are not in the United States have been labeled a voice for the voiceless and it’s meant as a compliment but it’s not because in order for there to be a voice for the voiceless, you are accepting that there are so many voiceless people. Then the voice for the voiceless becomes the representative, the spokesperson, the token, and all of that. I refuse to be any of those things.

I believe that we should be abolishing the conditions of voicelessness. That’s a whole social and political project and this book is only one small part of that. I also always quote Arundhati Roy, who says, “There’s really no such thing as the voiceless. They’re only the deliberately silenced or the preferably unheard.” That’s what we should be paying attention to. When we say a voice for the voiceless, we’re silencing so many people.

Alison: Is there something else that’s not in this memoir, something else you wanted to put to rest? That’s a great thing, you want to put to rest the idea of the voiceless. Any other things either about the refugee experience?

Viet: We have been and we will be living through the so-called refugee crisis for a very long time and I don’t think of it as a refugee crisis. I think of it as a global crisis that is a failure of all of our societies and all of our states but we blame refugees instead. We blame the victim for all these other things that we as a part of Western societies have helped to create. That’s what I hope people will take away from this if they read this book. It is about refugees and it is about what refugees mean to this country. It’s a challenge in a lot of ways because when we refugees come here, we’re meant to be the proof of the American dream.

Anybody can make it here. Yet for me, I have to reconcile that with the fact that refugees wouldn’t be in this country, many of us if it hadn’t been for America’s wars in different countries, and then for us to arrive in this country, we become settlers on indigenous land. That’s something that needs to be discussed and reconciled with. Then ultimately, as a whole, I think refugees helped to regenerate this country and make it better.

Alison: Before we let you go, your novel, The Sympathizer is going to be adapted for screen. I know the strike has a lot of things stopped at the moment. What can you tell us about the screen adaptation at this point?

Viet: Well, it stars Robert Downey Jr. I think the budget went up 50% when RDJ came on board but it also stars a lot of really talented young Vietnamese actors from the United States and from Australia. Hoa Xuande plays The Sympathizer, he’s amazing, and numerous others. I think this is maybe the first big-budget production that features a lot of Vietnamese Americans with tons of speaking roles for grounding and centering the southern Vietnamese but also northern Vietnamese perspective on what happened during this war and Americans just aren’t used to that. I hope there’s a shift in the understanding of this history because of the series.

Alison: Viet Thanh Nguyen will be speaking tomorrow night at the 92nd Street Y in conversation with Min Jin Lee. The name of the memoir is A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History and A Memorial. Thank you so much for coming to the studio.

Viet: So much fun talking to you.