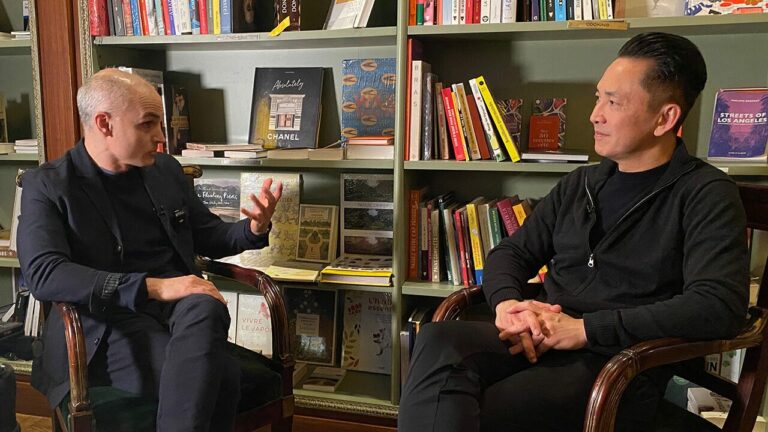

The modern age, Edward W. Said poignantly observes, is largely the age of the refugee, an era of displaced people from mass immigration. Writing about what it means to be a refugee, he admits, is, however, deceptively hard. Because the anguish of existing in a permanent state of homelessness is a predicament that most people rarely experience firsthand, there is often a tendency to objectify the pain, to make the experience “aesthetically and humanistically comprehensible,” to “banalize its mutilations,” and to understand it as “good for us.” Rare is the literature that can meaningfully and empathetically capture the scale, depth, and magnitude of the suffering of those who are today displaced and rendered homeless by modern warfare, colonialism, and “the quasi-theological ambitions of totalitarian rulers.”2 It is not surprising therefore, as Said suggests, that the most enduring stories about being an exile come from those who have personally been exiled themselves, ones like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Eqbal Ahmad, Joseph Conrad, and Mahmoud Darwish, who have embodied the experiences of living without a home, without a fixed identity, and without a country. Pulitzer Prize-winning Vietnamese American writer and academic Viet Thanh Nguyen, a refugee himself, is one such rare voice in American literature today, a voice that has been a relentless force in making visible, through storytelling, the highly diverse and multifaceted experiences of Vietnamese refugees arriving, settling, and living in different parts of the United States since the Fall of Saigon in 1975. Yarran Hominh, A. Minh Nguyen, and Arnab Dutta Roy interviews Viet Thanh Nguyen for The APA’s Asian and Asian American Philosophers and Philosophies, Fall 2023, Volume 23, Number 1

Viet was born in Ban Mê Thuột, Việt Nam (spelled as Buôn Mê Thuột after 1975) and came to the US with his family as a refugee in 1975, and was initially settled in Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, one of four camps that were set up for Vietnamese refugees. After earning a PhD in English from the University of California, Berkeley in 1997, Viet moved to Los Angeles for a faculty position at the University of Southern California, where he is currently serving as University Professor, Aerol Arnold Chair of English, and Professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature. Prior to gaining prominence as a creative writer, Viet was already a noted academic with influential publications in areas of American Literature, Ethnic Studies, and Asian American Literature and Cultures. Some of his notable academic publications include Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America (Oxford University Press, 2002) and an edited collection titled The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives (Abrams Press, 2018), which features essays by displaced writers from a wide range of locations, including Afghanistan, Bosnia, Chile, Ethiopia, Hungary, Iran, Latvia, Mexico, Ukraine, and Vietnam. Viet’s debut novel, The Sympathizer, a spy novel set during the Vietnamese refugee crisis of the 1970s, won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. The novel also won many other prestigious awards, including the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, the Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction from the American Library Association, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature in Fiction from the Asian/ Pacific American Librarians Association, the Edgar Award for Best First Novel from an American Author from the Mystery Writers of America, and the Dayton Literary Peace Prize. Viet’s other notable works of fiction include a collection of short stories titled The Refugees and a second novel, The Committed, which is a sequel to The Sympathizer. In his memoir, A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, a History, a Memorial, which is set to be released in October 2023,

Viet reflects on his own life journey as a creative writer, an educator, an academic, an activist, a family man, and a refugee, connecting personal events to larger historical trajectories of colonization, refugeehood, and nationhood. Viet’s writings, both creative and academic, are a poignant meditation on the complexities of coming to terms with one’s identity and culture, especially in the face of current global problems such as the climate crisis, mass immigration, mass displacement, war, and colonialism. His actions highlight in fundamental ways that modern stories of immigration and exile are never monolithic. As his novels and short stories reveal, the process of arriving in a new country and starting a new life can be relatively smooth for some. For others, such as the protagonist of The Sympathizer, it could be a process filled with the horrors of violence, loss, and unthinkable tragedies. In this long-form interview, which we conducted via Zoom on March 14, 2023, at 4:45–6:15 p.m. EST, Viet offers a detailed glimpse into his life and everyday experiences as an educator, a thinker, a writer, an activist, and a human being, reflecting not only on what it means to survive in thecurrentUSpoliticalclimateasarefugee,apersonof color, and a member of an ethnic minority, but also on what it takes to build and foster communities of resistance and solidarity dedicated to empowering—and improving the lives of—the most vulnerable and disenfranchised in our society.

CONVERSATION

Minh: Where did you grow up and what was it like, Viet?

Viet: I came to the United States in 1975 and settled first in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, lived there for three years, and then moved to San Jose, California, where I grew up from 1978 to 1988, and then I left my parents’ home and became a young adult. Those thirteen years in Harrisburg and San Jose would be how I would define my growing up. In Harrisburg, I had a happy childhood because I didn’t realize what was actually taking place with my parents’ refugee experience and the entire context of race and war that would eventually become major concerns for me. I was somewhat oblivious to the context of a refugee camp and being a refugee and the fact that we were resettled first through Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, which I’ve finally written about in the memoir I just finished. I talk more in the memoir about being a refugee in the context of settler colonialism and indigeneity, things that I was not thinking about as I was growing up. 1978 to ‘88 in San Jose was a deeply influential period for me because then I became conscious of myself as an other, watching my parents struggle to survive as refugee shopkeepers living a very difficult existence, hit by violence, worried about all the relatives that they left behind in Vietnam that they were sending money home to because it was obviously a difficult time in Vietnam, as well. I gradually became aware of all these issues around labor, around religion because my parents are deeply Catholic, and I, despite being sent to a Catholic school, came out an atheist. And politics, anti- communist politics, politics of the war in Vietnam that the United States and Vietnamese refugees were still fighting in their imagination. All of that would lead to the emotional damage that would become my material as a writer.

Minh: Congratulations on the completion of your memoir. I look forward to reading it.

Arnab: That memoir sounds amazing. I do look forward to reading it as well. How did you end up in your current interdisciplinary academic niche? How do you see the relationship between your academic work and your creative work? In particular, does your storytelling serve any pedagogical purpose?

Viet: I became an English major first in college because I deeply loved literature and reading, but I never thought about becoming a professor or becoming a writer until I also became an ethnic studies major. Ethnic studies is inherently interdisciplinary, and obviously the reason why is because it is responding not as much to a disciplinary problem as it is to a historical, political, cultural problem, which is identity, ethnicity, or race. Those types of issues need to be addressed in an interdisciplinary way. For me, interdisciplinarity becomes crucial because it is a methodological response to a world that has been fragmented and divided by the impact of colonization. Fragmented and divided not only in terms of national borders, racial borders, and ethnic borders, but also in terms of disciplinary borders. Singular disciplinary approaches have limitations in addressing a global system of colonization and oppression, which has an interest, I think, in doing things like creating a discipline of English, which is fascinating and beautiful, but also obviously may have certain unquestioned kinds of national and disciplinary assumptions. Becoming interdisciplinary was, number one, absolutely necessary for me to understand what it was to be an Asian American or a person of color or so-called minority in the United States. Then when I started to grapple more seriously with the legacy of the war in Vietnam and its aftermath, it was also obvious to me that I could not address my questions and obsessions purely through a disciplinary approach. My book Nothing Ever Dies is a mélange of different kinds of disciplinary tactics that I undertook. Honestly, to be interdisciplinary for me means to be sort of an amateur in a lot of these disciplines with the hope that the assortment of amateurish approaches would add up to a greater whole than the individual parts, and I hope that I was able to achieve that in Nothing Ever Dies. None of the disciplines that are deployed in that is as deep as a disciplinary specialist could be, but the whole assortment I felt gave me a larger picture of the war in Vietnam and its aftermath and memory.

I never wanted to become a professor. That was not something that I was aware of growing up. The word “professor” was never mentioned in my house. I wanted to be a writer as a kid, but I became a professor because it was my day job. That was my way of paying the bills, and it still is. I prefer to keep my life separated in this way because being a professor as a day job can be challenging. It’s got all the typical problems that having a day job would entail. Being a writer, in contrast, is my passion. Because it’s not tied to an employer or something like that, I don’t have any of the usual day job complaints that many people have, including writers who are doing that as their profession, for example, as creative writing professors. I never want to go down that road. But being a writer and being committed to the importance of storytelling has been important for me as a teacher and a public lecturer because I think most people outside of academia respond to stories. Academics may think they (academics) don’t respond to stories. They respond to theories and philosophies and arguments and so on. But in fact, I think a lot of academics have someone like me in mind, and that’s perfectly fine. Their works still spoke to me through the beauty and power of their voices and their art. One of the things I’ve carried away from that experience now as a writer is, of course, that I believe in narrative and beauty and art, but I also believe that I don’t have an obligation to try to speak to certain audiences. If I, as a young Vietnamese refugee boy, could respond viscerally to Philip Roth or to Balzac or to William Makepeace Thackeray, then people who are English or Jewish or Russian should be able to respond to my works, too, even if I’m not writing for them. I absolutely believe in that. I also believe that it is important to have books and narratives featuring people like you or like me. The content of it does matter, but the art of it should transcend the content as well. That’s one of the biggest takeaways as I reflect back upon the impact of that self-education I had in secretly do respond to stories, and most people outside of academia do prioritize stories. Storytelling becomes a great method, for me, of persuasion. I can use storytelling to advance arguments and theories and philosophies in ways that are not academically structured but would hopefully deliver a philosophical conclusion to my audience at the end of the story, whether the audience are my students, whether the audience is a general public of some kind.

I do believe that academic argumentation can be delivered narratively. I differ from a lot of my colleagues in this way. Nothing Ever Dies, for example, is a book that was written as a narrative. I wrote that book in a very linear fashion, from beginning to end, telling the story and structuring the book in a way in which, contrary to the usual academic fashion, the entire argument is not put at the beginning, but instead the argument reveals itself as the narrative goes along. Hopefully, that makes the book compelling to read from a narrative point of view.

the library and in literature.

Minh: Was your family supportive of your personal, academic, and professional journeys, including your ambition and aspiration to become a writer?

Viet: I’m lucky that my parents were a little bit liberal in regards to education. They prioritized high standards in educational accomplishment for my brother and me, and my brother set that standard very high by going to Harvard and Stanford. That was just supposed to be what we were supposed to do in our family, and I was the failure because I went to my last choice college. But they were liberal in the sense that they didn’t make me become a doctor or a lawyer. They did not throw a fit when I became an English major, and my older brother helped out a lot by saying, “Tell them you’re still doing pre-med,” and then telling me to do pre-law when I quit pre-med, and so I was able to hold them off. But then when I said, “I’m going to get a doctorate in English,” they were actually okay with.

Yarran: Viet, you’ve already said a little bit about this, but would you expand a little more on how your upbringing and early life affect the kinds of writing that you engage in, whether creative, academic, or otherwise?

Viet: I think of the early reading that I did in the San Jose Public Library because I didn’t own any books of my own. We were too poor for that, or my parents had other concerns besides books. The immersion that I had in the San Jose Public Library was a deeply intellectual and emotional experience for me as a child and an adolescent, and it imprinted on me a certain passion for narrative, for poetry, for images, and for beauty. Looking back on it, it was very clear, obviously, that almost everything I was reading was not about people like me. Most of it was about white people. Most of it was about Europeans. In retrospect, I don’t actually have a problem with that because I think that those writers that I was encountering were not writing with that because it was still a doctorate. They weren’t thrilled, but they were still okay with that. But the expectation was always that I had to get a job, so there was intense pressure on me to find a job as a professor, which is not an easy thing to do.

I never did tell them that I was going to become a writer. That was going too far. It was way too hard to explain that to my parents because there are no degrees. There’s no job. I couldn’t say someone was going to hire me as a writer. I did that on my own. I did it secretly, and I think the first inkling that my parents had that I was doing this kind of stuff was when some of my early short fiction was translated into Vietnamese. I remember I brought home to my parents a story that is in The Refugees as “The Other Man.” It had a different title when it was first published. But “The Other Man” had been translated into Vietnamese, and so I brought the story home and gave it to my father, a businessman, deeply Catholic, and culturally conservative. “The Other Man” is about a Vietnamese refugee man who comes to San Francisco in 1975 and discovers he’s gay, and there’s explicit sex in the short story. My father never mentioned that short story to me again. The next inkling they had of my writerly ambitions was when The Sympathizer was published, and I brought it home. He was very proud of that book. He wanted me to take a photograph of him holding the book, and he’s been proud of all my books since then. I don’t think he’s read them, but I don’t think that’s necessary. They’ve already suffered enough. Why make my parents read my books, too? But the thing is, I think they’ve accepted the writerly identity, and it doesn’t hurt that The Sympathizer won the Pulitzer Prize. That solved all my problems, any credential problems with my career as a writer, for my parents.

Arnab: I’ll actually be teaching “The Other Man” next week in my class. So this is amazing. A speculative question: If you had not pursued writing or academia, what would you have done as a profession?

Viet: I would be an unhappy, depressed, and alcoholic lawyer at this point.

Minh: Like the protagonist of The Sympathizer, you are a big fan of whiskey, is that right?

Viet: Whiskey, yes. Thankfully, I’ve cleared my desk for this video interview. I did have a bottle of whiskey right here as of last night.

Yarran: What would you change about the profession of writing and academia, in particular your disciplines, and how might we go about actualizing that change?

Viet: I think what I would change about the nature of academia, and it also affects writing because so much American writing is carried out in academia, is the corporate nature of the university. I’m at a university that is intensely focused on its endowment, its fundraising, its hospital system, its real estate, its political influence, and so on. The work of intellectuals in general but also very specifically the work of humanists and artists is either window-dressing in a system like this or highly marginalized or both. I think there’s a distinct relationship between the corporatization of American academia and this outcome where intellectual work, the humanities, and art is undervalued. The solution? I don’t know if there is a solution. I think that the American university system is completely embedded in the operations of American capitalism. I don’t see a way of undertaking this radical transformation. I think that potential solutions would probably have to take place alongside and outside and within the university in incremental ways in terms of collective education, free education, projects like that. I try to think of what my life would be like if I resigned or retired from academia, and I think that there’s great nobility in teaching, for example, and I would like to continue that but outside of academia and with other kinds of projects. Again, within academia, simply because of the way that the university has become so deeply entrenched within corporate relations, I’m very pessimistic that we can change that part of it.

Yarran: To follow up quickly, you mentioned earlier the importance of narrative for shaping the ways in which people see the world and engage with the world. I wonder what you think of that as a role that you like teaching outside of the academy. First, I wonder in what forms you have engaged in that activity. Second, do you think that narrative in general is a form of doing that outside of the academy?

Viet: I think that the narrative work, for me, takes place outside of the academy in the times when I go out and engage with non-academic audiences. I give a lot of public lectures, and I’ve written a lot for magazines and newspapers. Narrative is a really important strategy in both those cases in terms of telling stories that ultimately try to present arguments and persuade people. The academic thinking that we’re all engaged in has been very important to formulating some of these ideas, but most people don’t want to hear academic arguments delivered in an academic way. Narrative becomes a vehicle for trying to carry out my pedagogical work outside of the academy. For example, when I give public lectures to audiences of a few hundred to several hundred people in Idaho or Minnesota or Virginia, where I’m going tomorrow, I feel that for forty- fve minutes or an hour and a half, I have this audience. Most of them haven’t gotten up and walked out on me. They’ll listen, right? They’ll listen.

I tell jokes, and I tell stories. I get them comfortable and then deliver the punches that narrative allows me to do. Over the last several years, the lectures have started of with my refugee experience and my parents and so on and so forth and worked their way through representation and Asian American issues and the Vietnam War and ended up with a critique of the American dream as a euphemism for settler colonialism. I’m telling people in all these different places, including West Point, where I also had to go give one of these lectures, that this is a country that’s built on democracy and freedom and also on genocide, enslavement, war, and colonization. I think that’s kind of an accomplishment. I don’t think most Americans in many of these places hear that, especially from someone like me, a Vietnamese refugee who they expect to come out there and give them a narrative of gratitude or rescue. My lectures and the other stuff that I write for newspapers and magazines are designed to give a different narrative to unsettle settler colonial assumptions that become so embedded that many of us who are Vietnamese refugees or Asian Americans are wrapped up in that.

Minh: A follow-up question, please. Have you ever been canceled or been close to being canceled?

Viet: No idea.

Minh: That means you haven’t?

Viet: I think that, for example, when The Committed was published, it was reviewed on the front cover of The New York Times Book Review by Junot Díaz, whose writing I greatly admire. I tweeted about it, and then people got mad because Junot Díaz had been canceled. Therefore, me accepting the endorsement of Junot Díaz was therefore me endorsing whatever he’d done or allegedly done. That wasn’t quite cancellation, but it was getting to the point where a few hundred people were like, “Woah! How dare you!”

Arnab: Twitter is a dangerous, dangerous place.

Viet: That’s one reason why I said that Twitter is a cesspool. And why I got out. Let me say one thing. Real cancellation is, in fact, there because in Vietnam most of my books are not allowed to be published in Vietnamese, and we weren’t allowed to shoot The Sympathizer in Vietnam. I think that is cancellation but by government power, which is the real cancellation. And I’ve been told that there are some Vietnamese Americans who don’t like me because they think I’m a communist. The Vietnamese Government thinks I’m an anti-communist. There are many Vietnamese Americans who think I’m a communist. Now, they refuse to read my work. So is that cancellation? I think that basically is. Maybe things are being said in Vietnamese that I haven’t heard of because I don’t follow the Vietnamese media and social media that closely.

Minh: Thank you for that clarification.

I remember, though, when I was a kid, one of the books that I picked up in the San Jose Public Library and really loved was Voltaire’s Candide. That’s philosophy masked as a fable, and it totally worked. I was probably twelve or thirteen or even younger when I read that book. Obviously, I didn’t get it, most of it, but I was entertained by it. Looking back upon something like that as I wrote The Committed, I see part of what I’m doing in The Sympathizer and The

Philosophers and Philosophies is a journal published by the American Philosophical Association. It comes as no surprise that most of our readers are presumably philosophers. Your work—creative, academic, or otherwise—is very philosophically informed. For instance, as pointed out in the Acknowledgements, you “have discussed, drawn from, or quoted in the text” of your novel The Committed the following authors, many of whom are philosophical thinkers broadly construed, and their works: Theodor Adorno, Louis Althusser, Simone de Beauvoir, Walter Benjamin, Aimé Césaire, Hélène Cixous, Jacques Derrida, Frantz Fanon, Antonio Gramsci, Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, Julia Kristeva, Emmanuel Levinas, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Voltaire. What do you think the value of philosophy is? How important is philosophy to your own work? Who are your philosophical influences and why?

Viet: I think, obviously, philosophy broadly defined is really important to me but also generally important to everybody. Our lives as Vietnamese refugees, for example, have been completely shaped by Adam Smith and Karl Marx or by Western notions of democracy and freedom and things like that carried out from Rousseau onwards. There’s that sense of the general importance of philosophy, but then there’s the academic sense of philosophy, which is oftentimes completely boring. I remember trying to take an intro to philosophy course at UCLA, walked in and sat for one day, and then I walked out. “This is so boring! I don’t get it.” That’s a remarkable accomplishment by an academic professor to make philosophy boring, but he did it.

Committed is carrying out a Canadian story with my narrator. I was convinced that novels could be vehicles for philosophy, and that’s not an original thought. Look at Dostoevsky and those other major influences on me. I think people, in general intelligent readers, are perfectly capable of engaging with philosophy when it’s expressed in a narrative fashion, for example. That was the part of the commitment behind The Committed, and in The Committed, the philosophy is more explicit than it is in The Sympathizer. I think The Sympathizer is a very philosophically driven novel, but most of that philosophy is sublimated behind action. In The Committed, I wanted to make the philosophy a little more explicit because it is a novel that is about a deeply traumatized person whose life has been shaped by philosophical ideas, who has to rebuild himself and therefore engage with his own philosophical foundations and question them. I felt that there was a narrative reason in The Committed for there to be an explicit discussion of certain philosophical and political ideas. Some American readers, I think, reacted by saying, “Why is there so much philosophy in this novel? It feels like a graduate seminar.” This was from book reviewers. They weren’t quote, unquote “average” readers. They were book reviewers who were perplexed by the appearance of philosophy in a novel. This is, to me, an indication of how middlebrow American literary culture is that even specialists have a hard time grappling with the presence of philosophy in a novel, whereas the French, who, I assume, would be offended by the novel because it’s very critical of French stuff, were like, “no problem.” There was never a question from French audiences about the philosophy in the novel. They were perplexed by the fact that I didn’t like Johnny Hallyday, their French rock icon.

For me, writing The Committed, it’s a novel about gangsterism and crime and about philosophy as a form of action. That’s where I find philosophy to be really powerful. It is about ideas, obviously, but to me, the most important philosophy that I engage with is the philosophy that thinks about the implication of ideas into our everyday lives where they manifest as action—not necessarily as graphically entertaining as gangster shootouts, as it is in The Committed. But going back to the Karl Marx idea, here’s somebody who wrote incredibly dense philosophical work that would then lead to mass revolutions and millions of people dead. That’s real action right there. That’s where I find philosophy to be really alive or present in the works of people like Sartre, Fanon, Kristeva, and so on.

Minh: Would you consider your novels to be novels of ideas in the tradition of people such as Milan Kundera?

Viet: I hope so. I hope other people think so, as well. I think part of the problem here is that within the culture of the United States, a writer like me is seen first and foremost as a minority writer, a Vietnamese refugee writer, an Asian American writer, and therefore assumed to be writing about those adjectives versus writing about the non-marked issues that occupy the so-called “great novelist,” whether they’re great American novelists or they’re great European novelists. The great American novelist can write about America, and the great European novelist can write about ideas. You brought up Kundera. No one has a problem calling him a novelist of ideas, but when was the last time a so-called minority writer was called a novelist of ideas?

We’re supposed to be writing about our identity and our trauma and all that. All of which is important, but to me part of the project of my own writing is to argue implicitly and sometimes explicitly, which is when people got annoyed, that there are ideas at stake in these so- called identity issues that have been placed upon us and that some of us willingly take up. The

have a political language for talking about that difference. I think that is still true today for many people. People without a political consciousness, without a sense of solidarity, without a sense of history treat their identities in ways that can be deeply reactionary and, by being reactionary, can affirm the very histories that produce their identities as negative identities in the first place.

Coming to Berkeley as a student and becoming an Asian American was really crucial for me. That’s an identity, a deeply politicized, historicized identity. But I chose to become an ethnic studies major instead of an Asian American studies major because I also believed in solidarity. I believed that if being an Asian American was important, it was also because it was important in relationship to other so-called minority populations in the United States. In fact, the first ethnic studies course I took was Intro to Chicano Studies, which was actually very important for me because I grew up in San Jose, California, a city with a very large number of Latinos, including friends of mine. Identity in relation to solidarity has always been one of the most crucial dialectics of my life. I think that dialectic is still important because you still see, I still see people with very explicit identity commitments who don’t have a sense of solidarity and who are themselves therefore vulnerable to reactionary sentiments, like racism against other populations that the memoir is very explicit about this. In fact, the memoir is called A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, a History, a Memorial because it’s partly about me and my family but also about the history and the ideas and so on. To a certain extent, the memoir gives an explanation about why it is that a Vietnamese American novel is also a novel of ideas so long as the novelist can reject the framing that is placed upon the novelist by a racist white supremacist society that doesn’t believe a refugee can write about America, that instead, a refugee can only write about being a refugee. I think, for me, I’m definitely a writer of ideas but also a writer of identities and a writer of action. None of these things is irreconcilable for me.

Arnab: The theme of this special issue is “Identity and Solidarity,” two concepts central to Asian and Asian American studies and to the ethnic studies disciplines more generally. How have those two concepts played a role in your work and in your life? should have a greater sense of solidarity with. So I think our ongoing task always has been, in the era of colonization and hopefully decolonization, that we both have to develop politicized identities but always in relationship to solidarity with other politicized identities.

The relationship to questions of cancellation and censorship and power is, I think, also clear because when we look at the current political climate and cultural climate of the United States and Florida, where you all are at, or at least two of you, the rhetoric around cancellation is itself deeply ahistorical because you could argue the whole history of colonization has been one of extremely violent cancellation by those in power, including now the cancellation of the histories of colonized cultures, and all that enforced with physical and symbolic violence. The cultural efforts, the civil society efforts of colonized peoples to bring to light and to hearing what has been done to them and what is still being done to them is a fairly soft

Viet: Identity and solidarity have been absolutely crucial to my own intellectual, political, artistic development so far as identity and solidarity work dialectically with each other. Obviously, I don’t think solidarity is possible without identity, and identity by itself, without solidarity, is a deeply problematic place to be. For me, growing up in San Jose, my only identity was a confused one, being a Vietnamese refugee who knew he was different but didn’t response to the hard history of violent cancellation that’s already been practiced. The anti-wokeism efforts, the anti- cancellation efforts on the part of conservatives and some liberals is a deeply strategic or a highly naïve response that doesn’t acknowledge this longer history of colonization. I think deeply strategic or highly naïve because it depends on who’s carrying out these programs. I think your governor, Ron DeSantis, is deeply strategic. I think he knows what he’s doing, but I think there’s a lot of people who are just naïve and are just accepting the rhetoric of wokeism and cancellation without understanding this longer history of colonization.

If we have this dialectical relationship between identity and solidarity, we can bring out this history and say that affirming our identities today is not simply an effort at cancellation. It’s, in fact, a deeply political and programmatic effort at decolonization. I think that someone like DeSantis isn’t exactly wrong when he says that this political movement for what he calls cancellation and wokeism is a threat to his vision of the United States. It is a threat to his vision of the United States. It is a fairly significant and mortal battle that we’re engaged in. So long as we understand that it’s not simply a superficial political struggle but, in fact, is a political struggle and cultural struggle over the very meaning of this nation.

Yarran: I want to phrase this more as an invitation. I’d like to invite you to say or to talk about what you think is most exciting about Asian and Asian American studies at the moment, particularly thinking about identity and solidarity. Instead of asking, “What directions do you think Asian and Asian American studies should take in the future?” I’d like to ask you to note some directions that are occurring at the moment that you want to emphasize as speaking to those issues of identity and solidarity that you’ve just mentioned, especially with our current political climate.

Viet: I think that we’re in what might be called a third wave of Asian American studies. I think the first wave would be obviously inaugurated by 1969, 1968, and the beginning of an Asian American movement that would lead to Asian American studies. The second wave would be the theorization of Asian American studies that was inaugurated in the 1990s. The third wave has been relatively recent, probably in the last decade to two decades, because the first two waves were defined by a commitment to the nation and to citizenship, not an unproblematic commitment or an unauthorized commitment but a commitment nevertheless to those frameworks. I think the third wave has been much more cognizant of the limitations of nationalism and citizenship, including, especially in the United States, monolingualism with a focus on English, a claiming of the country, a claiming of the language, and so on. All of which are important. But the third wave of Asian American studies has been much more open and committed to international Asian American studies or a recognition of how Asian American studies is carried out in Asian countries but also a recognition that Asian American studies is itself US- centered and therefore vulnerable to American nationalism, exceptionalism, and imperialism in its very methodologies. Therefore, a third wave of Asian American studies has to be multilingual, comparative, international, multinational, and so on. I think that is where a lot of the exciting work has been done and is being done.

For example, at my university, Asian American studies is now mostly transpacific Asian American studies. All of my graduate students end up doing Asian language study, and a lot of them go do fieldwork in Asia as a part of their Asian American studies work so that the transpacific turn in Asian American studies is indicative of all these concerns from the third wave. Another element of a third wave in Asian American studies is the awareness and focus on settler colonialism and indigeneity. If you think about the fact that Asian American studies is at least partly born from the work of Orientalism and Edward W. Said, and that work is completely based in a critique of colonization that includes Palestine and settler colonization there, then Asian American studies if it’s to be true to that intellectual genealogy has to engage with a very broad definition of the Orient and its relationship to places like Palestine and to settler colonization. The other dimension of settler colonization that’s also really crucial is that Asian Americans become citizens and settlers. What does that mean for us to claim equality, liberation, justice, and so on as citizens when all that is built on settler colonial projects either within the United States or in the Pacific Islands?

What does it mean for those of us who are refugees to engage in that same kind of narrative, that we reject, for example, the kind of warfare that the United States carried out overseas and then come here and become citizens, and continue to participate in settler colonial violence domestically and the ongoing work of the military-industrial complex? The third wave of Asian American studies has very productively complicated originary notions of how important the United States is as a frame for an Asian American studies project.

Minh: My next question has to do with pain. Your works of fiction, whether one thinks of your novels or short stories, often speak to experiences of pain: the pain of war, the pain of loss, the pain of adjusting to a foreign land, the pain caused by racism and xenophobia, the pain of leaving loved ones behind, etc. As a writer, how do you prepare yourself, psychologically and emotionally, to embody, to speak to, to represent such myriad experiences?

Viet: I think that, for me, all those questions about confronting pain and trauma, both of the personal kind but also the collective and historical kind, are inseparable from the pain of writing. To become a writer, in my case, was fairly painful. It did involve about thirty years of living with the challenges and the hardships of being a writer. I’m not complaining about that, but I think for me it’s true that learning the art and all of the various technical aspects of writing was a very difficult experience. So was the experience of living with rejection and obscurity and disappointment and all that. Enduring all of that was inseparable from confronting the pain and the trauma of the content of my writing. These two things were inseparable. I had to go through all of that pain of learning to become a writer in order to confront the pain and the trauma of the histories that I wanted to deal with. The discipline of becoming a writer, I think, is related to the discipline of being able to confront the pain and the trauma. It’s only by doing both things at the same time that I could write a book like The Sympathizer and then eventually write a book like the memoir I just finished. The Sympathizer and The Refugees are about confronting the pain and trauma of the collective historical experience of being Vietnamese either in Vietnam or in the diaspora. But the memoir I just finished is about confronting the individual pain and trauma within my own family, which was really hard to do. I couldn’t have done it thirty years ago, and it took the thirty years of writerly discipline to be able to confront the internal issues within my family and myself.

Finally, I think that it helps to have a sense of humor. I don’t know if I could have done these things without developing a sense of humor. No one who knew me as a college student, for example, would have said, “Viet has a sense of humor,” certainly not in the next decade. Part of learning the narrative art has been also learning the comic art of satire and self-satire, and that’s obviously manifested in The Sympathizer, which then became the preparatory ground for me to be able to write a memoir, where I’m dealing with the very painful subjects within my own family, and which I obviously treat very seriously but I also treat with a lot of humor. People sometimes read The Sympathizer, and they’re surprised that I could write a novel about war and violence and torture and war crimes and so on and still make it kind of funny. They’ll read the memoir, and perhaps they’ll think, “Wow, writing about mental illness and domestic disturbances and things like that, and you’re still cracking jokes?” Well, one of the ways by which I could try to absorb all the pain and trauma is to also laugh at it, laugh at them, or laugh at myself at the same time.

Minh: A follow-up, please. You talked about the pain of writing. On average, how many hours a day do you devote to writing? What’s your writing routine if any?

Viet: One thing I tell writers is that you do have to put in the hours to be a writer. I say 10,000 hours because I think that’s not an inaccurate figure. But it doesn’t matter whether you do these hours every day or whether you simply do them over twenty years or thirty years, whenever you can. That was my solution to it. I don’t write every day because I can’t, because I’m a teacher and a professor. That affects the writing, but I did put in all those hours eventually. That’s the writing routine, and again, that’s part of the discipline. For The Sympathizer, I did write every day. That was a very ecstatic and unique moment in my life, but every other book I’ve written has been written in the fragments and the margins of a life that’s also committed to the profession of professing and also the life of parenting and the personal obligations as well.

Arnab: Your works of fiction highlight many different stories of immigration. For some of your characters, the process of immigrating to the United States is relatively smooth (though not easy by any means). For others, such as the protagonist of The Sympathizer or the short story “Black- Eyed Women” (from The Refugees), it is a process filled with the horrors of violence, loss, and unthinkable hardships. As a writer, what do you want readers to take away from reading about such diverse experiences?

Viet: I would want the readers to be moved in some way. I think about my own readerly responses to short stories or novels or poems that I’ve loved, and my reactions have always been threefold. First, I’ve been transported in some way by the narrative or the image. Second, I’ve been emotionally moved in some way. Third, I’ve been provoked to think in some way about what I’ve just read. I hope that those three things are all elements of what readers take away from the stories or from the books. Now, not every reader is going to take those elements away. Some readers will not like what it is that they encounter, and I think that’s fine, too, because I’m also fine with this idea that if I’m committed to a certain notion of my art at the aesthetic and political levels, I’m also committed to this idea that art provokes. It doesn’t just move. It doesn’t just make us feel better. It doesn’t just offer us a reflection. Art can really also annoy or anger us and unsettle us, and not everybody is going to react positively to such an experience. I think that, as a writer, I’m perfectly comfortable with this idea that some readers, I think some minority of readers is going to have a negative reaction to the work.

Yarran: Your stories are a poignant reflection on the complexities of coming to terms with one’s identity and culture. Your characters often clash, struggle, grapple, compromise over what it means to be an American in a society that largely sees you as different, foreign, or othered. Your characters often struggle over the question of how to belong, whether to assimilate fully or hold on to distant cultural values and practices. As a refugee, did you yourself ever experience some of these struggles or conflicts and did these experiences play a role in shaping the complex themes of identity and culture in your works of fiction?

Viet: I think about one of my teachers, Maxine Hong Kingston, whose work I encountered when I was a teenage college student, and how my encounter with her work was initially one of befuddlement. I didn’t understand what I was reading, but I spent thirty years periodically returning to her work because I teach it and because I think of her work as being important to me precisely because it did befuddle me. It led me to come back continually to deal with the complexities of what she was doing. In relationship to my own work and its impact on readers, I hope for some of that same impact. Now, if readers are immediately compelled and entertained, that’s great. But if readers are also sort of put of initially, that’s also fine because maybe the coming-to-consciousness that you’re talking about is sometimes a very delayed process.

Sometimes a work can increase our level of consciousness precisely because it already speaks to us. I get a lot of responses from readers who don’t have to be persuaded, but the work does mean something to them because it gives them a heightened understanding or heightened insight into some kind of problem that’s meaningful for them, like the problem of being Asian American or being a Vietnamese refugee and so on. But I also hope that the coming-to-consciousness issue might be there even for readers who initially reject or hate the work because maybe they are unsettled by being confronted with an idea or form that they didn’t expect, either in general or from someone like me. That’s also my hope for when I go give public lectures or write public essays and so on. The idea of coming to consciousness and the role that my work plays in that is a complex one because I think there’s multiple audiences, multiple kinds of readers for this work. That’s why I think that I’m willing to allow my work to be a negative influence on some people because sometimes the negative influence is more powerful and more provocative than the positive influence.

I think, for example, about Samuel Beckett, whose plays I’ve seen. Honestly, I don’t understand them. I don’t get it. But talking about writing as philosophy, his work is deeply philosophical, and the impact of the work has been such that I’ve never forgotten it. There’ve been many novels that I’ve been deeply entertained by and liked, but I’ve totally forgotten about them. Beckett’s work, however, as confounding as it is, including moments where I’ve fallen asleep watching his plays, still affects me, and I continue to come back and grapple with it. That’s sort of the high standard that I have in mind for my own work. I would like novels like The Sympathizer and The Committed to entertain people, but I am perfectly okay with them provoking people in a negative way, too, in the hopes that the negativity will stay with them and force them to confront that negativity at some point later on.

Yarran: Funny that you described it in that way because my initial response to The Sympathizer, at least the first half of it, was I was annoyed by the character’s voice. I couldn’t get inside the narrator’s head. It was only with the really overtly satirical scenes in the second half of the novel with the scenes of the filming of

the movie that I started to be able to approach the novel in a slightly different way. By the time I got to The Committed, my mindset towards the characters had changed with the kind of dialectic through the acting of the narrative. In my own experience of those two novels,

there was that kind of initial alienation, I guess one could say, about particularly

various things about the voice of the narrator but then coming back to it through that kind of unreliability and recognizing that unreliability. So, yeah, thank you.

Viet: Going back to the cancellation issue, we do live in an age in which, I’m not saying this about you in particular, but we do live in an age in which a lot of readers want to feel comfortable in their reading. They want to have difficulties explained to them, aesthetic difficulties or political difficulties and so on, because they don’t want to be unsettled. But one function of art is not to explain itself, and I think that, in some ways, The Sympathizer and The Committed, for example, have didactic elements in them, very deliberately so. In other instances, I refuse to be didactic and explain why certain things are being said or done. Some readers are coming into the work, again not talking about you in particular, and they want to have their worldview affirmed in some way, and it isn’t. It’s dislodged, and they want the comfort of an explanation. Novels don’t always offer that. I think that is, to me, symptomatic of some of the debates around cancellation because sometimes people want to cancel something because they’re unhappy. They’re unsettled. They want an explanation, and it’s not forthcoming in a way that’s pleasing to them. Instead of trying to grapple with the work as art or philosophy and so on, they just refuse to countenance its continuing existence in their world.

That is carried out by people of different ideological backgrounds. I can safely say that that is also carried out by people within my general ideological universe. I disagree when that’s being done because there is an irreconcilability between political orthodoxies and what it is that art and philosophy sometimes need to do, which is to reject orthodoxies of all kinds. Unfortunately, cancellation is oftentimes a manifestation of orthodoxical impulses from people of all kinds of different backgrounds.

Minh: Let’s talk about history and representation. History plays a prominent role in your works of fiction, whether one thinks of representations of the Vietnam War (the American War) or the Fall of Saigon. Do you see your writings as doing important work in educating readers about such historical events? In other words, do you see your writings as trying to undo the damage caused by misrepresentations and omissions on the part of mainstream American media that often amount to jingoistic, propagandistic, and Orientalizing portrayals of such histories?

Viet: Oh, absolutely. I think that the collective work that I’ve done from Asian

through the Vietnam War and refugee experience and colonization is all meant to counter dominant misrepresentations. That being said, I think that fictional work that only does that is kind of boring.

I just think that the language around “representation matters,” misrepresentation, corrective representation has a dimension of treating art as if it’s performing a function of affirmation, which is important but is also far from enough for what art should be doing. That’s why I think that I keep returning to the issue of my hope that my writing not only does that work of counter-representation against dominant misrepresentation but also counters the counter-impulse, the corrective impulse, the impulse for therapy, the impulse for amelioration that people who have been traumatized by misrepresentation often feel.

Art that only does that, that only offers a positive reflection back to the people who have been negatively misrepresented, is quite insufficient and, again, boring. If we use the metaphor of the mirror to say, talk, writing an essay, or writing a novel. It’s ethically and politically problematic and complicated to speak for others, even if that action is necessary to engage in this work of counter-representation that we just talked about. A lot of decolonizing literature and so-called minority literature is caught in this problem of speaking for an other. We need our writers to speak for us, for others, ourselves as others, that we’ve been misrepresented, we’ve been distorted, and therefore we have to offer a positive mirror, that’s a dangerous metaphor because when we hold up a mirror, even to people who have been negatively misrepresented, we shouldn’t be just trying to give them a positive self-reflection. This is why I think that, for example, some Vietnamese readers don’t want to read my work, whether they’re communist or anti-communist, because the mirror that the fiction holds up to them is not a mirror of positive reflection. It’s a mirror that shows all the dimensions of our human faces, from all the beauty to all the ugliness at the same time, and, again, there are a lot of readers out there who don’t want to see the ugliness. They just want to see the beauty.

Minh: So art can play a corrective critical function, and it can be entertaining, non boring, in your sense?

Viet: Absolutely. But again, I’m just trying to emphasize that the corrective and parts, as important as they may be, are themselves insufficient to an artistic project because what’s the impulse behind correcting the representation? It’s to offer a truer representation. But is a truer representation only the positive? No, I think a truer representation is, in fact, something that reveals that we are neither victims nor villains. We’re neither angels nor demons. We’re all these things in one subject, one subject as an individual, one subject as a collective or a community. Again, a lot of people who have been damaged by misrepresentation don’t want to confront that more complex level of representation.

Arnab: On March 1, 2023, you delivered the 18th Annual Anne and Loren Kieve Distinguished Lecture at Stanford University. Sponsored by the Center for Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity (CCSRE), it is titled “Speaking for an Other.” Would you give us a sense of what that lecture is about, especially in relation to future directions of your work? Does the theme of “Speaking for an Other” tie in any way to issues of identity and solidary?

Viet: The lecture at Stanford was a foreshadowing of the memoir that’s coming out. There are two dimensions here that I’ll highlight. One is that it’s titled “Speaking for an Other” because the talk highlights the ethical and artistic problems of speaking for an other, whether that is because we assume the role of a spokesperson through the act of representation, whether it’s the act of giving a but what happens when that action of speaking for an other is potentially negative or a betrayal of the people that we’re speaking about?

I think that’s always been the case. It’s especially the case when we are dealing with fiction or memoir, both of which I’ve now engaged in. I used that talk to shift the terrain for me from just the broadly political terrain of speaking for an other, whether the other’s Vietnamese or Asian American, for example, to the very personal dimension of speaking for an other who is my mother. That is also speaking for an other as well. What happens when our work is not just in a potentially fraught relationship with the larger community but with intimates, people who are very, very close to us? One of the conclusions that I reach in the memoir is that sometimes the other is someone who is too close to us. We could imagine that other as someone who is, for example, part of a community that is right next to ours or a nation that’s right next to ours, but the other is someone representational who, too close to us, is oftentimes the people we love. What happens when we speak about them? How fraught is that action? I think, for me, the talk and the memoir grapple with the relationship between the need to speak a truth, which is hopefully what we do as writers and philosophers, and what happens if that truth is also taken as a betrayal by the others we are speaking about or speaking for.

Finally, the talk was also about this question of identity, which is, what if the other is within us? How do we know that we even understand ourselves? I think a lot of my work is concerned with that question. Sounds pretty obvious in relation to The Sympathizer and The Committed. In fact, to write this memoir, I had to write the memoir in the voice of the Sympathizer. In other words, in writing The Sympathizer, I had to create a whole persona to approach this complicated history of the war and its aftermath, and then to write my memoir, which I didn’t want to do, I had to use another persona that I had created in order to talk about myself. The novels and the memoir are deeply related in a formal and philosophical sense because they’re all about self and otherness when the self and the other are within us. Treating myself and the other not as simply these vastly huge political and cultural positions but also as positions of internal difference. The novels and the memoir are about individuals confronting the otherness within themselves, and so part of the memoir is about how much I know and don’t know who I am. For example, the memoir talks about the unreliability of my own memory when it comes to writing about my mother and about how her mental illness was so deeply traumatic for me that I had to contain it and forget huge portions of my own life and my mother’s life in order to just cope with her otherness, the fact that she herself was other to herself because of her mental illness, and then the deep impact it had on our family. Writing the memoir was actually really, really difficult because it was precisely about trying to confront this otherness that I had buried within my own self.

Yarran: I was struck by part of your final response to Arnab’s last question when you brought up writing for your mother in your memoir and the way in which you had to adopt the narrator’s voice in The Sympathizer. Ocean Vuong does something remarkably similar in On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, for similar reasons and perhaps with similar intentions: simultaneously to be able to write of that person that you care about and to hold them at some distance so as not to impose on them. I want to ask you about that connection. If you have any thoughts that you’d care to share, I’d love to hear them.

Viet: I think Ocean engages in some fictionalization of some autobiographical experiences in that novel, possibly for the reasons you indicate, although I think he’s also said it’s not an autobiographical novel. For me, the memoir is purely a memoir. Gina Apostol, who read the memoir in draft form, thinks I am theorizing through the Mother as an Other. Sounds about right to me.

Minh: Is there a sequel to The Committed? Or is this the end?

Viet: There has to be. There has to be a season three of The Sympathizer TV series if we make it that far, but no more. No more. I fantasize that after the third novel in The Sympathizer Trilogy, I can be done with the war in Vietnam. I’ve written many books about this topic now: war, aftermath, memory, colonization. I would like to be freed from those things. I don’t know if it’s going to happen. I would like to write about other things, and we’ll see what happens after the third novel in The Sympathizer Trilogy. But the third novel in The Sympathizer Trilogy does continue the excavation into war and colonization.

Minh: Do you have a title for it yet? A tentative title?

Viet: The Sacred.

Minh: The Sacred?

Viet: As in, is nothing sacred? And the answer is, no, nothing is sacred.

Minh: Oh, I see. Very good.

Arnab: Whether you move on to other topics or you continue writing about these topics, I feel that you’ve changed a lot of minds. You’ve definitely changed mine. I first read your short stories. Then I read your novel The Sympathizer. It was very transformative for me, and it has been transformative for my students as well. Some of my graduate students last semester were just blown away reading your novel, and it was a difficult time for them because they read your novel around the time Hurricane Ian hit us. Some of my students were without a home, then they were reading this novel, and I feel that kind of added to the impact because we had to switch to online in the middle of the semester. Many of my students told me that novel was the only thing for many of them that kept them not thinking about their own reality, and for that I’m very grateful.

Viet: I love that story. Thank you so much. I think that part of why I like going out to give public talks is meeting readers and hearing their stories about their own lives and concerns, but also their stories about their engagement with whatever it is that I’ve written. I haven’t heard that story yet about solace in the face of a hurricane. But that’s great.

Arnab: Yeah, it was something.

Minh: Viet, just in case, Arnab was referring to Hurricane Ian, the deadliest hurricane to strike Florida since 1935. Our school shut down for two weeks, so that’s what the experience was about. Well, are you pleased with how the HBO adaptation of The Sympathizer has turned out so far?

Viet: So far, it’s hard to say because I haven’t seen any actual episodes. They’ve moved from LA to Thailand as of this week, and they’re starting to shoot in Thailand for the next six weeks. I think the experience has been very positive so far. It’s been a very positive set. I heard from many people that this seems like a very unique production in terms of how down-to-earth everybody is, from Park Chan-wook and Sandra Oh and

Robert Downey, Jr. down to all the newer Vietnamese and diasporic actors that we have. The vibe has been great, and the scripts look pretty good.

Minh: Do you have a role in shaping the script?

Viet: I met with the writer’s room, and the majority of the writer’s room was actually Asian women (Asian American and Asian Australian). I read the script and gave feedback, but it’s such a hugely collaborative enterprise. There’s literally hundreds of people making this TV series. Again, it’s going to be very hard to say what it’s going to be like until we actually see the finished product with all the different collaborative elements in place.

Minh: Talking about television and film, did you think the Oscars got it right this time?

Viet: Also, Everything Everywhere All at Once was produced by A24. A24 is producing this TV series as well. I just had a publicity meeting with HBO and A24, and this is right before the Oscars. The A24 publicity person for this TV series is also the one who did the Everything Everywhere All at Once publicity campaign. I think the Oscars did get it right, surprisingly right. I was a little bit cynical in advance that Everything Everywhere All at Once would take home some of the trophies, but it took home so many trophies. Hopefully, it does indicate a shift in Asian American representation in front of and behind the camera. We’ll just have to wait and see, and we’ve been hoping for a while. First, we had Flower Drum Song, then we had Joy Luck Club, and then we had Crazy Rich Asians, and the progress seemed to be so incremental and slow. Then this movie just came down and kicked all the doors open, we hope. We hope. I think the real measure is whether Ke Huy Quan gets major leading man roles with this.

Minh: What do you think about Ke Huy Quan’s acceptance speech in which he shared that his journey to the US started on a boat and that he spent a year in a refugee camp?

Viet: Honestly, I was in a bar when his speech came on, so I couldn’t hear his speech, but I could see him emote the entire time. He seems like a great guy, and I’m so happy that he won. I did read some of the highlights afterwards, and I’m very proud of him that he foregrounded being a refugee and the boat experience. At the same time, he did conclude that portion of his speech with an invocation of gratitude to the American Dream. Much of my work complicates that narrative. I think that there still remains a lot to be written about the movie and the placement of its actors and the whole issue of the awards and everything because I’m quite aware that awards are partly about art but also partly about a lot of other things, about politics, society, and culture. Not to take away from Ke Huy Quan, but the narrative of the grateful refugee is something that America understands.

Minh: Okay, thank you, Viet. Just to let you know, this is Viet’s spring break. Thank you very much for taking out ninety minutes of your time—I know you have young children—to share your reflections, your experiences, your thoughts about the past, the present, the future, everything everywhere all at once. Thank you so much, Viet, and good luck with everything. I look forward to the publication of your memoir.

Viet: Well, thank you, everybody. Thank you, Yarran and Arnab, for your questions, very detailed, very thoughtful questions. I appreciate all the care that all of you took, including Minh, obviously, for initiating this interview. I look forward to seeing it in APA Studies on Asian and Asian American Philosophers and Philosophies. Never thought I’d be in conversation with philosophers, so it’s pretty awesome for me to see that happen. Thanks, again!

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This conversation was edited for clarity and length. We would like to thank Viet very much for participating in it. Many thanks to his Chief Author Assistant / Executive Assistant Titi Nguyen for arranging the interview and our Editorial Assistants / Research Assistants Vivian Nguyen and Brent Robbins for recording and transcribing it. In addition to Vivian and Brent, Nhi Huynh provided comments and suggestions on this piece, for which we are grateful.

NOTES

- Edward W. Said, reflections on Exile and Other Essays (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), 173.

- Said, reflections on Exile and Other Essays, 173.

- Approximately seven months and one week after our conversation, 92nd Street Y, a New York-based cultural and community center also known as 92NY, canceled Viet Thanh Nguyen because of his stance on the Israel-Palestine conflict. For accounts of this episode, see Jennifer Schuessler, “92NY Pulls Event with Acclaimed Writer Who Criticized Israel,” The New York Times, October 21, 2023, accessed October 30, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/21/arts/92ny-viet-thanh- nguyen-israel.html; and Jennifer Schuessler, “92NY Halts Literary Series After Pulling Author Critical of Israel,” The New York Times, October 23, 2023, accessed October 30, 2023, https:// www.nytimes.com/2023/10/23/arts/92ny-pauses-season-israel- hamas-war.html.