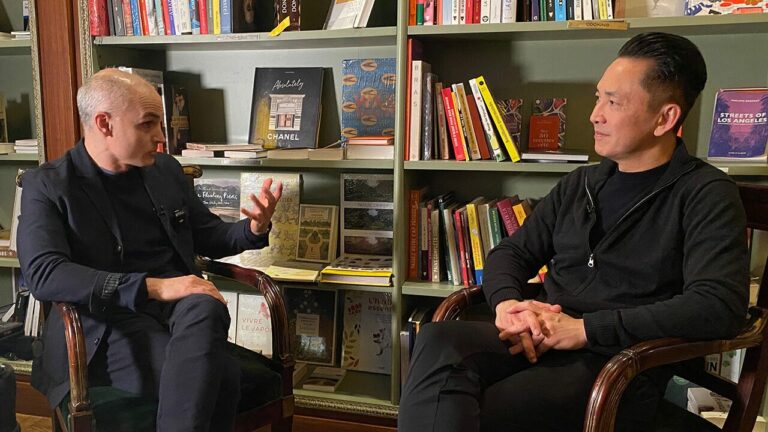

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s new memoir, A Man of Two Faces, is an unconventional and impeccable personal narrative that tackles the author’s own life alongside larger themes of culture and colonization. Nguyen joined us live at The Grove to talk about understanding his own story through writing, his interpretations of memory and more with Miwa Messer, host of Poured Over

This episode of Poured Over was hosted by Executive Producer Miwa Messer and mixed by Harry Liang.

New episodes land Tuesdays and Thursdays (with occasional Saturdays) here and on your favorite podcast app.

Miwa Messer:

This is Poured Over, a show about stories presented by the booksellers of Barnes and Noble. I’m Miwa Messer. I’m the producer and host of Poured Over and we are taping live in Los Angeles, and I’ve been waiting to say that for about three years. Thank you all for joining us tonight. Viet Thanh Nguyen needs no introduction, but I’m going to do it anyway because I love this dude and I love his work, and you guys clearly love his work too, because I’m watching all of these smiles happen, and I’m very, very excited to have this conversation. Dude, thank you so much for joining us.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Miwa, I’m so thrilled to be here with you.

Miwa Messer:

So I grabbed a line from the memoir because I do this. Born in the year of the pig when Tanviet reborn in America, all caps trademark, as Viet Thanh Nguyen. History performs your cesarean as it does for all refugees to America, all caps trademark, delivering you as that mythological subject, the Amnesiac, rootless, synthetic, New American. I love this line. I love this book so much. Here’s the thing, if you’ve read The Sympathizer, if you’ve read The Committed, you know Man with Two Faces, none of this is a surprise, right? This is driving The Sympathizer, it’s driving The Committed. But I want to ask you about the subtitle, a memoir, a history, a memorial. Honestly, we’ve been talking about this book as a memoir for what, three years, four years?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Mm-hmm.

Miwa Messer:

But let’s start with the subtitle.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

The subtitle is the way it is because I really resist writing memoirs. I’m sure you’ve all read memoirs. I’ve read memoirs. For me, part of the idea of the memoir is that it’s supposed to be about the individual and the individual’s trauma. Honestly, I hope none of you ever feel the need to write a memoir because if you do, it means something bad has probably happened at some point. Part of the idea of the memoir, both for writing and for reading it, is to get that revelation like what has happened to this person or their family that’s so screwed up. It is in the book, it is about me and my family, and I’m pretty screwed up. I had to discover that. I was in denial most of my life. I’m a perfectly normal, well-adjusted person, and my wife [inaudible 00:02:06] said, no, you’re not.

I was like, okay, maybe I should reconsider. But I also resisted writing the memoir because especially if you happen to be a person of color, immigrant, refugee, Asian American, and you write a memoir in the American context, it’s really hard to overcome the framework of the American dream, which basically means for you as a writer, we know you’ve suffered. We know your parents and grandparents have suffered. We know that you’ve suffered. Even in the United States as great of a country as we are, we know that immigrants experience racism, et cetera. But hey, look at you. You wrote a memoir, congratulations. You’re the living proof of the American dream. That is something that I felt I could only overcome by actually acknowledging it. I think if you don’t acknowledge it in the actual writing, then it’s so easy for people just to super impose that ideological layer on top of what you’re saying.

So I wanted to put that in the subtitle to tell you it’s not just a memoir, it’s also a history because it’s about my vision of the United States, which is not everybody’s vision. It’s a memorial because it’s about my parents, especially my mother and what she went through. The other problem here is that when you write about Asian mothers or Asian anybody, again, the idea is they suffered so much. Then the temptation for a writer, I think is sometimes, especially the children, to treat your parents’ story as if it’s extraordinary. Your parents’ stories are extraordinary, but they’re actually also really ordinary.

Everything my mother went through and my father went through when I talked to other Vietnamese refugees, they all went through that if you are a Vietnamese refugee or the children of. Refugees and nothing bad happened to your family, you’re exceptional. It’s normal that you went through something horrible or your parents did. So I wanted to acknowledge that my mother’s story was extraordinary for her and for me, but normal because of what history did to us.

Miwa Messer:

Well, this is something we really need to do in any Asian community. We don’t talk about this stuff. We need to start talking about this and we need to start claiming our stories back. But one of the things that I do love about this memoir is I recognize the voice. I was telling Viet backstage, I was like, dude, I’ve even read your PhD thesis, which if you guys want to read, it’s available. You can do this.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I would just say my best friend from high school did say to me, I keep that book by my bedside to help me fall asleep. So that just fair warning.

Miwa Messer:

It is fair warning, but I like to do my homework before I sit down with a writer. Especially if you know Viet’s work, there’s not a lot that’s going to necessarily be a surprise in the memoir. Okay, how many of you have read Refugees The Short Story Collection? Okay, some of you have homework to do. All I’m saying is it’s totally worth getting. But there is a short story that I’m going to ask you to riff on a little bit that is based on a very scary thing that happened with you and your mom and your dad at home in San Jose.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

When my parents came to San Jose, California in the 1970s as refugees, they opened a Vietnamese grocery store there called the Saigon Mai, and it’s the typical refugee shopkeeper story. They worked there constantly. Downtown San Jose in the seventies and eighties was not a safe place for anybody, especially for Vietnamese people and shopkeepers. So my parents were shot there in the store on Christmas Eve when I was nine. That opens the book. Then when I was 16, a gunman came to our house and broke in, that’s my mother and my father and me and said, get down on your knees. My father and I, being the men that we are, got down on our knees and my mother, being the woman that she is, ran past him screaming out into the street and basically saved all our lives because then he turned around and tried to follow her and my dad slammed the door shut behind him.

So for me growing up, this was normal. I had no other frame of reference for this because, again, this was happening to other Vietnamese refugees too. This was part of the stories. My parents would always say, don’t open the door to strangers because Vietnamese gangsters can come in. This is the era of the home invasion in San Jose. Of course my mother opens the door because it’s a white man there instead of a Vietnamese person. My way of coping with that was to pretend that I was normal, that this was normal, and that I was never going to write about this stuff because it was boring.

Miwa Messer:

Right.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Real people wrote about whatever it is that white people experienced, not whatever it is that we Vietnamese refugees experienced. So the story you’re talking about, war years in the refugees, it took me a long time to write that story because again, I felt like our lives were not worth writing about. So I had to work my way up to the autobiographical. And then to actually write this memoir again was to acknowledge that what seemed so normal and trivial to me is normal and trivial. But you know what? That’s the stuff of the memoir. All of you have normal trivial stories, but they matter to you. That’s the challenge of being a writer, is to go there that seems so normal and trivial and to realize how powerful it is.

Miwa Messer:

I mean, yes, but also why would we separate history from a personal memoir? I don’t think you can separate the two.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I was deeply inspired by my teacher, Maxine Hong Kingston, whom you probably have heard of at least, and hopefully read. But I do recount how, of course I was the worst student in her class at Berkeley. She told me to my face, “You were the worst student in the class.”

Miwa Messer:

From Asian F to the worst student in Maxine Hong Kingston.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

She gave me a B plus. That’s the Asian F, right? I was like, oh my God. It sucks to say that stings to get the B plus. I was like, oh my God, I know what this means when I got the B plus. In her book, the Woman Warrior, on page five of the Woman Warrior, she says very directly Chinese Americans,. She addresses her audience. For those of you who are writers or readers, the question of the audience is very important. Do you know who your audience is? If you don’t know who your audience is, then you default into the implied audience, which is the white audience.

So I think Maxine was being very smart in 1976 by saying Chinese Americans, that’s her audience. She says, Chinese Americans, how do you know what in you is Hollywood and what you is peculiar to your family? I took inspiration from that. So this book, there’s a direct paraphrase where I say Vietnamese people, Vietnamese refugees, Vietnamese Americans, how do you know what is history and how do you know what is just your own personal trauma? I think for so many of us, we don’t know. We don’t know where to draw the line. Would we normally be this screwed up or is it because we went through war and colonization and refugee experience and all that other kind of stuff that totally messed up our families?

Miwa Messer:

I think that’s true across Asian America. I don’t want to limit it just to … certainly Vietnamese Americans have been defined in a very different way. But if you look at the Japanese-American experience, certainly the Chinese-American experience, [inaudible 00:08:32], the Hmong community, but there is still, to me, a cohesive Asian America and not just as a political identity. It’s a more matter of saying, Hey, I recognize there’s something in my story. I grew up in the suburbs of Boston. So like Boston Chinatown, three blocks, one place to get Dim sum. My grandmother would send us Nuri from Tokyo. We weren’t in California. We couldn’t get it here, so we had to rely on my grandmother to keep us in seaweed.

So it’s all of these things though where you’re constantly aware of being the other, and there’s this piece of America, all caps trademark, that really wants to make sure that if you’re considered other, that you remember that first and foremost, regardless of what your other is. I’m not saying it’s just limited to Asian American, but there is this idea that the other, and it does make some fine writers. Sorry about that. You did get a Pulitzer out of it.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, yes I did. I like to think I deserved it.

Miwa Messer:

Yes, you did.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

In all honesty, I’ve been on both sides. I’ve been on many jury committees now and all that kind of thing. I serve on the Pulitzer Board now. The reality is, of course, that it’s not just about merit because there’s a lot of worthy writers out there and worthy books. So what does it mean to get a Pulitzer Prize or any other prize? There’s so many social, political economic factors coming into play, and I’m very aware of that. So this book is also about what it means to be a writer and an Asian American writer because you’re absolutely right. It’s an honor just to be Asian as Sandra O said. It means that we can get Nori, we can get boba, we can get all this kind of stuff at H Mart, and that’s awesome. There’s a common Asian core. BTS is great and all this kind of thing.

I like to say though, to the younger generation, my students 20 something people, look, you’ve got all these kinds of things. Why are you still screwed up? I go to talk to a lot of college campuses and there are a lot of college students who say, I have the model minority crisis. My parents want me to do this, and I want to do that. I have an identity crisis. So from the sixties to the nineties, which is my generation to the present generation, the same stuff happens all over again. Why is that the case? So in the book I say, look, I don’t suffer from an identity crisis. I suffer from a political crisis. We wouldn’t be here, you or I, if it wasn’t for colonization and global warfare and all these other kinds of things. It’s not east versus west in terms of culture. It’s politics.

Miwa Messer:

I get to add a layer to it, because I’m Japanese and Taiwanese. If you know, you know. So, if I’m in Taipei, anyone over the age of 60 speaks Japanese to me, I’m like, hi, I am an American. It’s okay. Hi.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I just want to add to that because in the American context, one of the ways in which our otherness is contained ironically, is to keep it very American centered. So again, you’re allowed to be Asian American in this country now as long as you’re an American. So what does that actually mean? It’s very, very problematic because when I became an Asian American in college, I was very self-righteous against racism and all that kind of stuff. Then I realized eventually to be an Asian American is not just about struggling for our empowerment. If we’re also struggling for our inclusion, what are we asking to be included in? We’re asking to be the included in the war machine. How do we reconcile that? So for me to be a writer and an Asian American writer means also grappling, not just with what the United States has done, but what we do when we participate in the United States.

Then also you brought up Japan and Taiwan. That’s a whole nother history. I bring up in this book the fact that I think that the United States is a settler colonial country, and it’s a real problem for a refugee and immigrant to come here because then we’re like, oh, we’re achieving the American dream as settler colonizers, so we can be both a refugee and an immigrant and a colonizer. Then I go back to Vietnam, and I think my parents, I think were colonizers too because they went from the north to the south in 1954 along with 800,000 other Vietnamese Catholics, and they were settled in indigenous land in the Central Highlands with the aid of the government and the CIA and the US. What is that? How do we reconcile our existence if we think of ourselves as so-called minorities here in the US and we have to empower ourselves with this much more complicated history that’s transnational in which we’re not innocent. So that’s part of what the book tries to grapple with too.

Miwa Messer:

Oh, tries? Definitely does. Does really well in fact. But I want to talk about memory because you’re also talking about the structure of the book isn’t a stand … if you’ve had a chance to open it and just flip through it, you’ll see there’s a lot of white space, there’s a lot of textural change, there’s a lot of, do we call it poetry? You’ve talked about being a failed poet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I’m a terrible poet, but let’s say it’s poetry inspired.

Miwa Messer:

Okay, poetry inspired. All respect to the poets in the audience, but you’re doing things with language to mimic how fraught your memory is. I think this is really important to call out. The way you can’t separate the personal and the sort of global history. You cannot separate that. You also can’t separate language and memory and story because sometimes they collide in really weird ways and sometimes they collide in ways that are determined by other people. I think that’s part of the problem that sometimes we encounter when we’re trying to tell story.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

One reason I’d resist the memoir or resisted the memoirs, because oftentimes when you encounter a memoir, you’re encountering this sort of holistic reproduction of a life from beginning to wherever it ends up, and it’s very seamless. That’s not how I experienced my life or my memories even today. When I try to think back upon my past, it’s a bunch of fragments, and then I’ll try to reassemble it and turn it into a narrative. But in a sense, that’s actually very fictional because you’re creating a narrative of yourself that isn’t exactly how you actually experienced it. I don’t know how many people actually have a whole film reel playing in their head that’s a coherent narrative. Mine is all screwed up. Then I also think about how history blew up our lives. Our families were destroyed, our communities were destroyed. We were blown up all over the world with the diaspora and all that kind of stuff.

We were forced to cross borders. Borders were crossed when colonizers came into wherever our countries happened to be. Then here in literature, we’re expected to hee to borders. I don’t get it. There’s novels, there’s memoirs, there’s short stories, there are poems. Somehow we’re supposed to understand that there are these rules and conventions that dictate what we’re supposed to do. So when I wrote the book, I was like, why does prose have to look like prose? Who said that you have to have paragraphs and you have to have left justification. These are all just conventions. So I wanted to disrupt that partly out of fun, because it’s a lot of fun to write the book, but also as my formal response to the fact that our lives and our communities were shattered.

Miwa Messer:

This is also the guy who, remember, has reinvented The Spy novel, has reinvented The Crime novel, right? The Sympathizer is essentially a play on genre. The Committed is a play on genre. You’re mixing genres in fact. You sneak in some big ideas and some literary theory. There’s some literary theory in The Committed. That’s not a bad thing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Offended.

Miwa Messer:

It’s not a bad thing. That is not a bad thing. But I want to work in a couple of questions from the audience. One of the things I’m thinking about in terms of memory and language, you talk about being separated from your family when you were four. You go through the Philippines to Guam, to Pennsylvania, and when it comes to the point where you’re trying to get out of this camp, no one’s willing to take your entire family. So your parents go one place, your brother goes another place, and you are sent at the age of four. I just want to be clear, at the age of four, you are sent to live with strangers. Obviously you have very little memory of this, but what’s a thing that you carry today from that experience?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

When I was growing up, I certainly remembered vaguely that I had been separated from my parents at four years of age. Again, that was just normal. I was like, well, doesn’t that happen to everybody? So I just had to try to cope with that and not think about it. Then I had a child, a son, and he turned four. This at the same time that this is 2017. This is literally the same time when the Trump Administration was ripping children from their families at the border and losing them in the system and everything. I’m looking at my son at four thinking about what’s happening at the border and thinking if that happened to me as a parent, which I’d actually never thought of before, so self-centered, I’d be totally traumatized by that experience. But then I look at him at four years of age, and when you’re a child, everything is enormously magnified.

I realized that actually it was probably deeply traumatic for me at four years of age to be taken away from my parents. That’s your entire world when you’re four and you’re separated. So even now, I find it kind of hard to articulate and have to talk about it. I’ve talked to so many refugees with their own variations of particular stories where you just have to not think about the past. If you want to move forward and not just be totally screwed up, you just have to acknowledge that these terrible things happen to you, whatever they happen to be, and that you’re not going to look backwards. So I just did not look backwards until I became a writer. I remember Maxine wrote me a letter at the end of our seminar, and she said, you should really go seek counseling. I was like, no, I’m Asian. I don’t seek counseling.

Miwa Messer:

Yeah, we don’t do that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

We don’t.

Miwa Messer:

We don’t have feelings. No, no. That’s not part of the factory preset.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So I became a writer, but as a writer, that was how I tried to cope.

Miwa Messer:

Right. No, I get it.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah. My other writing teacher [inaudible 00:17:47] said, you don’t cut to the bone. I was 20 years old. It took me 30 years to learn how to cut to the bone through the writing to try to get back to these originary traumas.

Miwa Messer:

If I think about the stories in The Refugees, which took you what, 17, 18 years to really get together. Now granted they’re published after Sympathizer, but you wrote Sympathizer at a much quicker … two years. Two years compared to 17. But when I look at the difference in voice and craft and willingness, I could still see you sort of standing back from the work and the difference between The Refugees and Man With Two Faces, it’s not that they were written by two different people. It’s not that. But the willingness, you have to dig in to what you don’t know, it’s really impressive.

It’s really, really impressive because it’s not the kind of work that you can just sit down and be like, oh, it’s Tuesday. I think I’m going to write about this thing. It’s more like you have to sit and then you have to walk around with this stuff and you sort of have to play with it a little. You’re just rolling it around in the back of your brain until the story reveals itself. You talk about English coming to you with both conscience and memory, and the combination for a young person is kind of brutal. It does get a little easier the older you get, but you’re sitting down to write.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So I don’t want to be sentimental about this, but I became a father that really did change me a lot. You have to remember, I never wanted to be a father. I thought it would be the end of my life. Becoming a father and looking at children, what’s really interesting to me is seeing how unrestrained they are. Sometimes that’s a pain, but it’s also very inspiring because they have not yet learned to care about rules, genres, expectations, that kind of thing. Then they become older and they do. So you’re telling them color in the lines and they read their books in school and their teachers are telling them about literary genres and things like that, and they learn. Then some of them become writers like I did. So when I wrote The Refugees, I was extremely self-conscious about the short story.

How do I write a good short story and what are the rules? How do I get published in the New Yorker, which I never did. I was aware of audiences and expectations and judgments and norms and all of that. I think my entire writing career was first about trying to learn those rules and then about unlearning them. Unlearning them is actually extremely difficult because it’s about unlearning all the social and literary conventions in political conventions that I’ve acquired over my lifetime. I felt that was necessary in order to get deep inside, because again, these conventions prevented me from getting deep inside. Number one, finding the right form to talk about things, but then also again, finding the ability to destroy the American dream, which I felt had totally inhabited me. And I point this out because even many of us I think, who say, well, I don’t believe in the American dream. Are you sure? There’s the un-ironic American dream, which most people in this room probably disavow. That’s the rah rah rah wave your flag. But the ironic American dream, that’s really hard to get out of yourself.

Miwa Messer:

Okay, can we talk about the model minority here or do we wait? All right. Listen, model minority is part of it, right? And it drives me up a tree. It drives me up a tree.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

This is very intelligent audience. You all know what the model minority is, and you all know you’re supposed to say, Asian Americans are not the model minority, and we need Asian American writers because they’re not the model minority. They’re not the engineers and the lawyers and the computer scientists and all that. I think no, Asian American writers are in fact the model minority too, because maybe I would love your expertise here as a part of the book selling world. My friend Minsong has a book called The Children of 1965 where he argues it’s demographics. The reason we see the boom in Asian American literature in the last 20 years or so is because it’s the children of the immigrants who came in 1965 who grew up and went to all the good schools. So no, they didn’t become engineers, but they did the equivalent. They became English majors at very good schools, and then they went to get their MFAs at very good MFA programs, and they’ve been programmed to become writers. So it’s a flip side of the tech startup dudes in Silicon Valley, but it’s the same thing as mere image with the MFA model minority writer.

Miwa Messer:

I think there’s a piece of that which is absolutely true. It does make me a little nutty. I would like to see us be able to be people and to be a little messy and to not necessarily do this sort of tracked kind of thing. I say this as a person who did not do the track, oh, did not do the track career bookseller. I love what I do, but I mean, there’s [inaudible 00:22:24], there’s me. There’s not a lot of us.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think that it’s totally possible to do it, but I also think that we need to be cognizant of, again, how deep-seated the ideology is that subverts even this effort as Asian American writers to resist what’s been happening to Asian Americans.

Miwa Messer:

I also had a safety net though. I had a safety net. So I think there’s a difference when you have the freedom that comes with knowing that you can make a decision that’s actually yours, but not have to decide between whether or not you’re going to eat or pay your rent. Class is something we’re not great about talking about in general in America, and that’s certainly part of the American dream. But one of the things I do love about the Man With Two Faces is the way you blow up our approach to success, our approach to truth telling. You dig in and you tell things that you very specifically say, well, my parents would really super not like me to tell these. And guess what? I just put them all in a book that anyone can buy and read. Your parents ended up making a really nice life for you and your brother, and you guys were not working in the store after school.

They kept you in a place where you could study and do your thing and eat a lot of TV dinners and watch cartoons and be you kind of thing. And yet there’s a piece that’s missing. In a way, you’ve been able to change that with your kids, right? You’ve got two kids now. There’s a shared language. You can read to them. They can say, Hey, dad, read me a book. There’s a connection there. You talk about how when you were a kid, you’d go to the library, you get a whole backpack full of books, and the more you read, the further you got from your parents. That’s a wild idea. That is a totally wild idea that somehow reading and expanding your world shifts your relationship with the people who put you on the planet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, you brought up class. It’s true not just for immigrant and refugee writers, but also anybody who, through their education, creates a distance between themselves and the people who raise them, who they grew up with. So it’s inflected by class, also by race and nationality and everything like that. So yeah, that’s part of the pain of becoming a writer for some of us. I don’t want to generalize. There’s different kinds of writers. The kind of writer I’m talking about, the so-called Literary Writer, I feel that that’s who I am. I was lucky because I was traumatized just enough to be that kind of a writer, but not traumatized so much that I’m a terrible human being. I think that’s a very tricky balance.

Miwa Messer:

We vouch

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

My parents. I felt like I had a safety net too, because even though I grew up feeling like we were sort of working class because I didn’t get the toys that I wanted and whatever, and because my parents were getting shot, at the same time, there was never any worry really about money. Even though my parents neglected me in many ways, they also were not the stereotypical Asian immigrant parents who verbally abused me. They actually said they actually were actually very nurturing verbally. So I recognize how important that actually is. So you were talking about having this shared language with my children. Absolutely.

So I actually try to replicate what my parents did, which is actually to be affirming, to be affirming. You can do all other kinds of things to your kids to try to discipline them into whatever kind of person you want, but to affirm them is actually really super crucial to give them a sense of self-esteem so that they can emotionally withstand a lot of the things that will happen to them because I’ve known so many people who have been damaged deliberately or not by their parents, simply because if your parents are immigrants and refugees and they’re just struggling to survive and they’re coming home, they’re going to say things that they don’t mean to say necessarily, but they’re going to hurt.

I talk about how history ripples through me emotionally. For most of us, for many of us, that’s how we experience history. It’s not that we’ve directly witnessed war, but those of us who are children and grandchildren of refugees and immigrants, the history ripples the US emotionally because our parents or our grandparents witnessed that, screwed them up, makes them do and say things that they may not have done if that history hadn’t happened to them. So then we become the beneficiaries, good or bad, of the emotional damage that they experienced.

Miwa Messer:

I want to toss in a couple of questions about memory here for a second. I was trying to figure out how to do this. Your works tie in a continuous theme of memory. What inspires your different interpretations of memory and your new/previous works? Anything you haven’t explored yet?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh gosh. I think that I would just use that Maxine on Kingston class as an example, I was 19. I wrote an essay for Maxine about my mother and her commitment to the Asian Pacific Psychiatric Ward. That was a very difficult essay to write, and then I put it away into a box, and I didn’t look at it again for 30 years. For those 30 years, what I thought was my mother went to the psychiatric ward when I was a little kid, and then I opened up that box, I read the essay, and I realized, no, she went the year before when I was 18. But the effect of it was so terrifying for me, made me feel like a little kid that my memory just completely changed the facts of things. So that was a very vivid illustration for me. That memory is just completely unreliable.

Our memory will do all kinds of things to protect us in whatever way. It can happen to us when we’re fully functional adults. So memory is an incredibly tricky thing, and I think that’s one of the reasons why it’s been such a preoccupation for me, because memories, there are at least two versions of memory. One is the memory that you actively seek out. You sit down, you’ll think about something, try to recall it. Another version of the memory is memory that seeks us out. That could be random things, random trivial things, things that you did last week, but also horrifying things as well. That dynamic of memory is, I’m so fascinated by that because I think it’s a personal dynamic, but it’s also a collective cultural national dynamic. It helps explain a lot of the things that have happened to us and that we are doing as Americans, for example. Then to answer the second part of the question, at a certain point I realized that in fact, I had a sister.

Miwa Messer:

She’s 12 years older than you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

12 years older, right. I think my first memory of her actually happened when I was, it was probably the early eighties or maybe I was 10 or so. We got a letter in the mail, and all I remember was the photograph, a photograph of this young woman, a black and white photograph of this very attractive young woman. I was told that this is your adopted sister. I was like, what? I’m pretty sure I didn’t ask any questions because again, this is the way things are. All of a sudden you have an adopted sister. Now, I knew I had one obviously when I was four, but I didn’t have any memories of her. Then all of a sudden, this photograph shows up. So then from that point onwards, I was aware that we had an absent presence in this house of somebody we had left behind.

Again, not unusual for refugees and immigrants. Some people make it and some people don’t. I think that maybe for a lot of refugees and immigrants, but certainly for me, there’s a sense of alternate realities and parallel universes where if something different had happened, our parents made a different decision, our lives would be completely different. My brother at a certain point said, “You know why mom and dad didn’t leave us behind? It’s because we’re their children.” Meaning the adopted sister, adopted daughter did not count in the same way. That’s really horrifying to think about.

Miwa Messer:

Well, there’s also the girl child thing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Girl child thing. Yeah.

Miwa Messer:

My mother got to come to the States because she’s book ended by a boy and a girl on either side of her, and they’re like, oh, sure, you want to go to America? Okay.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So the question asked, what else could I write about? I swear to God, I never want to write another memoir, but if I did, it would probably be about finally going to Vietnam. I’ve met her once in person, but having a much more extended contact, but also to go back to where I’m not supposed to go to, because we fled from our town of Bunmetuit, which is the first town overrun in the final invasion of 1975. My father has said, you can never go back to Bunmetuit or now it’s called Bunmetuit, and I’ve never done it. So that would probably be what I would write about.

Miwa Messer:

It may just show up in a novel. There’s an undercurrent of you in every story, every novel. I promise you guys, when you pick up a Man With Two Faces, you’re going to understand that so much of this guy is on every single page of every piece of fiction he’s ever written. It’s wild to me how much you were willing. You’re much looser on the page in Man With Two Faces. But at the same time, even the shift in town between the sympathizer and the committed, when we go from Spy novel that’s slightly reserved. Are we playing with Gram Green? Are we playing with John [inaudible 00:30:47], to this filthy crime novel? I say that in the best possible way, filthy crime novel sent in the eighties in Paris, and now we’re here, and you’re like, oh, I’m just going to put it all on the page. Everything is going to be here. So I’m going to work in another question. Has writing about memory made it easier to understand the two worlds one lives in, or has it opened a new set of complexities?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think it’s left me with this awareness that I’m completely unreliable and untrustworthy to myself. I try to be reliable and trustworthy to my friends and family and so on, but part of the experience of writing A Man With Two Faces was to realize that I’ve been deceiving myself for a very long time, and I don’t think that’s actually that unusual. I think part of the argument I make in the book is the greatest distance that I experienced was the distance with myself, and how so much of myself has been a process of shrouding and hiding and all of that just to protect myself. Then to become a writer was learning how to try to pin down what that hidden self was.

So A Man Of Two Faces, there is the illusion that has happened. I have no idea if it has or hasn’t. So I hope that it hasn’t because an endless investigation of a self, which if I’d done it as a series of memoirs, would probably be just totally boring. But if I do it as novels where it’s not really me you’re seeing, but some chance muted version of me, it’s much more interesting.

Miwa Messer:

You did say we were getting a third novel at some point, right?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

At some point.

Miwa Messer:

It’s not like you promised us a due date, but you did say The Sympathizer and The Committed are part of a trilogy. Yeah.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah,

Miwa Messer:

You did say that. Yes. And that was like two years ago when we were talking, so I’m just-

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, then I had to write this book. I wrote this book.

Miwa Messer:

I know, you accidentally wrote a memoir.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

And now I’m writing a series of lectures. But after that, I got to write the third novel. Honestly, there’s a real pragmatic consideration. Number one, I promise. People know about it, but number two, there’s a TV series, and if it’s successful, then hopefully they’ll actually produce Seasons two and three.

Miwa Messer:

Which means we need more material.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah. We need that third novel for the third.

Miwa Messer:

We’re not handing that over to HBO. They can go to the source first.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

It would be really interesting if HBO wrote a novel and then I wrote a novel, and then they can pick and choose.

Miwa Messer:

No. This is not Choose Your Own Adventure. I would like to stick with the actual source material.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I think one difference between … the two novels are like you say, genre novels, Spy and Crime. One thing I envy about straight genre writers is that once you have the formula, I think you can just keep doing it over and over again. That’s hard, but you can still follow it.

Miwa Messer:

I don’t think you’re going to do that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

That’s what I mean. So I can’t.

Miwa Messer:

I don’t think you’re going to do that. You don’t think like that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

The third novel is going to be very different because I can’t talk any further about it, but I have some ideas. But it’s because he’s different. The context is different, and the genres are just vehicles to explore his concerns and who he is. So it’ll be quite a different genre than The Spy and The Crime genre.

Miwa Messer:

We can be patient maybe, kind of. I do want to quickly work in this. How did the transition from fiction to nonfiction writing feel and how did this differ in terms of what you chose to disclose? I feel like you’ve talked about the disclosure part, but let’s talk about craft for a second. This is not a genre ebook.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Man of Two Faces. No, yeah.

Miwa Messer:

It is pure you with some [inaudible 00:33:56].

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I have to say Man of Two Faces has a lot of influences, and I owe a lot actually to poets. When I was very young, a teenager and so on, I fell in love with poetry. But there was English romantic poetry, memorized-

Miwa Messer:

[inaudible 00:34:08].

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah, I memorized Byron and Shelly and things like this. Then I went to college, and I am sorry to say my poetry professors were really boring. They killed my love of poetry. So I didn’t understand anymore what is the connection between poetry in the world. I could see it when I was a kid and I couldn’t see it as a young adult. Then I started to read Poets of Color. There’s been a whole wave of really interesting poets of color, Natalie Diaz, Claudia Rankin, the author of Yellow Rain. But there’s just so many interesting writers of color, [inaudible 00:34:36] Sharif and Ocean [inaudible 00:34:39] and so on. I could totally see when I was reading them, what I couldn’t see when I was reading modernist poetry in college, which is that I could finally see the connection between form and politics and history.

I could understand why these poets are breaking up the form using white space, playing with the shape of words and things like that on the page. I could totally see why the formal experiments are related to the disruptions of history. So that’s all in the Man of Two Faces. So then the larger point, going back to the early point that I raised about genre, is I’m not that interested in genre distinctions. I think of myself as a writer, not as a novelist or a short story writer or poet or whatever. I’m a writer, so everything is writing. Some of the writers that have influenced me, like people like WG [inaudible 00:35:19], the German writer, when I read his fiction in nonfiction, I can’t tell the difference. It’s amazing.

I think the reason why I can’t tell the difference is because he’s a writer. He’s just going to use writing to talk about his obsessions. And his obsessions are very similar to mine about war and memory and genocide and trauma and national deceptions and self deceptions. He’s going to use both the fiction and nonfiction to grapple with his obsessions. I think that’s very similar for me. It wasn’t actually very difficult to make the transition because I think of myself, again, as a writer and not as someone who’s foremost preoccupation is with genre.

Miwa Messer:

Right, and Sophia Sinclair, you guys know the poet Sophia Sinclair? Cannibal. Okay. If you haven’t read Cannibal, please read Cannibal. I’m late to Cannibal. It is amazing. But she has a memoir out now called How to Say Babylon, about growing up in Jamaica. She talks about how for her language isn’t just the thing on the page, it’s how you embody it. That’s what I think of when I think of your work as well. It isn’t just the text, it’s a little bit of swagger. It’s definitely a little bit of swagger, which is nice to see, but there’s a swing that’s happening and there’s a connection that you’re making to this sort of larger world of literature that isn’t just you. If it happens to be genre, cool.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

The author of Yellow Rain is Mai Der Vangis, by the way. I’ll just start with her as an example of how to answer the question, which is when you read Yellow Rain, it’s a formerly very innovative book of poetry that is poetry incorporates a lot of documents dealing with this yellow rain that was dropped on the Hmong during the war. When I read it, I think part of the reason why I think Mai Der Vangis is playing with language, but also putting these documents in the book is because it’s not just yellow rain that kills people. It’s language that kills people. That’s what the Hmong are partly so angry about. They saw this being done to them, and then scientists and experts who are not Hmong are coming in and saying, no, you didn’t see what you saw. They’re using language to do this to them.

Likewise, when I’m writing, I think language for me, it’s not just an instrument. I think somehow the books that don’t interest me are when I feel as if the writer does not fully inhabit the language, and the language doesn’t inhabit the writer. They’re just using the writing as a way to tell their story. And that’s fine. But what really interests me is the fact that from my experience, and for me as a refugee, I was saved by language and destroyed by language. At every turn, language really mattered. Even when I thought I was saving myself through learning English and trying to become a writer, I was also destroying myself because the earlier example that you mentioned, the better I became an English, the more alienated I was from my parents. And you know what? I made that choice, and you get these books, but then the cost for me and my family is this other thing. So language for me is never innocent.

So that’s why when I write these books, it’s never secondary. I’m not just trying to tell a story. I’m also trying to figure out how I can use the language differently with each book because the story demands that the language be transformed and transforms me.

Miwa Messer:

I need sentences that are cut glass. I read for language first, and if stuff happens, great. If I connect with a character, great. I do not need to like characters. I just need sentences that are cut glass. That is what I need. You’re part of my pantheon of writers who do this really, really well. But when we talk about language, I want to bring in a couple of pieces of art that don’t technically belong to you, but I went down a rabbit hole. Viet has recently written an introduction to the Lover, the Marguerite DuRoss novel, and actually replaced the introduction by Maxine Hong Kingston. I re-watched Apocalypse Now for the first time in 20 years, and I have feelings. I have so many feelings about the language in both of those things. I have to say, going back to [inaudible 00:38:56], so you have a moment where you don’t remember if it was the movie that you saw first or The Lover, or if it was the book that you read.

I know for me, it was the book, but now having seen the movie, all I think of is that woman in the straw hat and the Citra and the, ah, it’s so annoying. But that image is really sort of stuck in my head, right? They are two fundamental pieces of art, world art. I remembered loving The Lover when I was … I don’t know, I must’ve been a teenager when I read it and thinking, wow, the language. If you’ve ever read Dura, she’s something on the page, and she’s so angry and she’s real and she’s writing about class, and she is not having it with any of these French people. It’s just great. I know in my heart that Apocalypse Now is an anti-war film. But dude, that movie, and I feel like we can’t talk about them separately. I feel like we have to talk about them as a whole because for certain people, they have defined Vietnam. You like Paris more than I do, and there’s a reason I don’t like Paris all that much.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

For me as a Vietnamese person born in Vietnam influenced by these histories, France and the United States are obviously very important because these are the colonizers and occupiers that shaped us. So Man of Two Faces is partly about acknowledging that I’ve been psychologically colonized. I can’t help it. In The Committed, the narrator talks about how it gets weak in the knees at the mention of a baguette or anybody speaking with a French accent. It’s ridiculous. But it works. It works at such an emotional and intuitive level for if you’ve been colonized. So part of the nature of colonization at the core of colonization and its seductions is power. The reason why French culture seduces and American culture seduces is because these are very powerful countries, and we respond to power, whether it’s at the national level or whether it’s in relationship to another person.

So that power can be seductive, it can be abusive and so on. So the French and the American National imaginations through Apocalypse Now and through DuRoss and so on, and these are just symbolic of many other works.

Miwa Messer:

Right.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

They have left an imprint on the global imagination about how to think about Vietnam, either through the lens of the dirty war or bad war that the Americans have the preoccupation with, or through the lens of romance and seduction and this tropical empire thing that the French did. So my situation relative to these entire canons that these two works symbolize, is that I acknowledge that they’re actually really great works of art. I respond as a writer to both of them very, very strongly. Then of course, the friction is how it is that I myself or people like me may appear in these works. You talked about the cut glass thing in the hands of lesser artists, these two works would be really deeply irritating. There are lots of lesser artists. There’s a lot of many-

Miwa Messer:

We’ve seen the ones that tried to xerox. Oh, yeah, no, that xerox copy is not good.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Right. That’s unacceptable. But the cut glass, I forgive a lot for good art. I think that Apocalypse Now is a racist film and it’s also a great movie. I think these two things are perfectly reconcilable, and I can totally watch that movie again and again because I respect the art, even if the art is built on this racism.

Miwa Messer:

I also think the first half is more honest than the second half. I just think it’s more honest to us as people in the world and everything else. Then that second half, I’m just like-

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, you said as an anti-war movie. I think that is a popular preconception of it. One of the things I insist in A Man of Two Faces is that a real anti-war story is actually not about the guns and the battles and all that kind of stuff. It’s about the death. It’s about the civilians. Because if you watch Jarhead the movie or read Anthony Swofford’s book, Jarhead, both of them talk about how the Marines who are getting trained to go to Desert Storm, were watching the Apocalypse Now as a war exercise.

Miwa Messer:

Yep.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So if it was an anti-war movie, it just went over everybody’s heads. And that’s the point. These movies are spectacular, and they feature guns and battles and young men dying. Nobody who’s a young man I think thinks they’re going to die.

Miwa Messer:

Oh, no, they don’t.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

They think they’re going to be the survivors. So that’s why it’s not really an anti-war movie that guy’s going to die. I’m going to live and I’m going to come back in glory. The real anti-war story is about those who don’t come back, those who are crippled, those who are disabled, those who don’t have body parts and so on, and about the civilians. You cannot watch massacres of civilians, for example, that have that be a pro-war story in any way. But of course, we don’t as Americans or really probably anybody of any nationality want to think about that. So we don’t actually want to hear the real anti-war stories, which is the stories that have no glory in them at all.

Miwa Messer:

It’s weird too, watching it, I was sort of transported back to Massachusetts in the eighties and stuff that you would hear from people sort of just casually, and it was kids hearing it from their parents. It’s wild how much that movie defined my life before I actually saw it. The pieces that people choose to carry around with them, I would love it if they all looked at themselves and figured out why those were the pieces they chose, because it’s fascinating. Or the people who … I grew up where McGeorge Bundy is from, and I went to college with dudes who wanted to be the next McGeorge Bundy, and I’m just like, y’all do not understand what that means. But okay. So all of these pieces of what you call the war, what a lot of Americans just shorthand as Vietnam, which I’m going to take this opportunity and remind everyone, it’s the name of a country, not a war. It’s all of these pieces.

You and I were both defined in very different ways by this moment in history. So for me to say, that’s only a refugee story, that’s only the story of a dude from San Jose, that’s really disingenuous. It’s not.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So I want to go back to an earlier question. I think about why I write and why I grapple with memory and everything. One of the reasons why is because memories shift and change over time, both as individuals, but also as countries as well. If you live long enough, you see that happening. So I’ve lived long enough, sadly at this point, and when I was growing up, you could assume that people all over the world had seen Apocalypse Now. Literally, I could go anywhere. I could bring up the Vietnam War and people would say, have you seen Apocalypse Now? In any country. That was how powerful this generational experience of the war in Vietnam was. I don’t know if that’s true any longer. I teach a Vietnam War class to my undergraduates. They’re 20 years old, let’s say on the average.

And 20 years ago, I could assume that a lot of them would’ve seen at least one American movie of the Vietnam War. Now, almost none of them have seen any of them. They may have heard of them vaguely by reputation, but there’s been a generational shift, I think, and that’s not just a matter of pop culture concern. It’s a matter of the national imagination. People sometimes ask, what have we learned from the lessons of the war in Vietnam? I would say we’ve learned all the wrong lessons. There was a certain period for 30 or 40 years leading up through 9/11, where people could say, okay, let’s not repeat the war in Vietnam again, and people would know what you’re talking about. Now, it’s really, I think the United States, every President, democratic or Republican, every Pentagon administration, they’re all about how we can fight the war better than what we did in Vietnam.

That’s the lessons that Americans have learned. That’s the wrong set of lessons. So I write because I feel that writers are lonely voices trying to say, wait a minute, I understand that the entire culture, the entire nation, whether it’s France or the United States, wants to forget, wants to move on. Nobody wants to hear the writer raising their hand and saying, no, wait a minute, let’s not forget. But I feel that that is in fact, unfortunately, part of my task at any rate, and no one wants to hear a broken record, but you have to have it. You have to have discordant scratching in the back of your mind saying, don’t forget, don’t just move on and someone has to do it, and that someone, at least in my life, is me.

Miwa Messer:

Yeah, but I don’t think it’s being a broken record when you’re claiming your seat and saying, Hey, pay attention. I think those are two different things. I think we have to keep repeating ourselves, because otherwise, pardon me, we’re going to forget.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, we have to keep repeating ourselves because our nations keep repeating themselves. Nothing that we’re seeing today I think is really new in the United States in terms of American history. It’s new to us, but if you look at the cycles of American history, we’ve committed genocides on a regular basis. We’ve gone to war on a regular basis. We’ve forgotten that we’ve done these things on a regular basis. Trump, Obama is not a do dynamic in American history, as I try to point out in the book. Only if our memory only goes back 10, 20 years, would we be shocked by how we could elect a black president and then elect Trump? But in fact, that contradiction between genocidal white nationalism and this idea of America as being democratically inclusive, that goes back to the origins of the country.

Miwa Messer:

Right.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

That is us. So we repeat over and over again. So I feel like as writers, unfortunately, I don’t think we can get over the past because, as Faulkner said, the past is still here. It keeps repeating. The illusion is to pretend that we have moved on and that history is linear, which is what the American dream is about. The ever greater union that we’re going to go towards, but maybe we’re not. Maybe we’re just going in cycles.

Miwa Messer:

Yeah, I’m a believer in the cycles model. Sorry. It feels like we’re doing that loop de loop de loop, and we just keep coming back. The good news is though, we have books, we have you. I knew this was going to run long and we could keep going, but we have some books to sign. So this is where I say thank you. I’m Miwa Messer. I’m the producer and host of Poured Over. Viet Thanh Nguyen, of course, is the Pulitzer Prize winning, and I didn’t get to say it earlier, even though I said I was going to do it, public intellectual. You can hear his series of Norton lectures, which I’m very excited about. Pulitzer Prize winning bestselling author, now memoirist, but also historian. So if you haven’t caught the other books, please go back and look at them really.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Miwa, thank you so much.

Miwa Messer:

Okay. This is great. Thanks.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Thanks everybody for being so patient.

Speaker 3:

Thank you for listening. Poured Over is a Barnes and Noble production. To help other readers find us, please rate and review the show wherever you listen to podcasts.