The two award-winning authors talked about memory, racism, and finding common ground among marginalized groups for Oregon Artswatch by Amanda Waldroupe

Bibliophiles who attended this year’s Portland Book Festival had a tough choice to make at 10 a.m.: Separate events featured New Yorker cartoonist Roz Chast, Oregon poet laureate Anis Mojgani, and novelist Tim O’Brien.

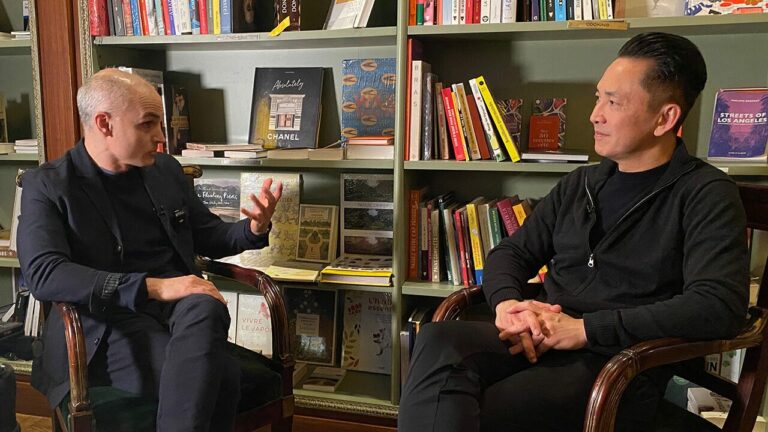

A fourth event featured two authors who packed the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall. Novelists Tommy Orange and Pulitzer Prize winner Viet Thanh Nguyendiscussed Nguyen’s newest book and first memoir, A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial.

Released two days before Saturday’s festival, A Man of Two Faces is Nguyen’s memoir about growing up and his family’s experiences as Vietnam War refugees — his family escaped South Vietnam before the Fall of Saigon in 1975, when Nguyen was 4 years old – coming to America, and Nguyen’s coming of age and growing up as a first-generation Vietnamese American in San Jose, Calif.

Nguyen’s books — The Sympathizer, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2016, and The Committed – dwell on trauma, memory, family, and loss. Although Nguyen remembers little about escaping Vietnam, he said he was an eyewitness to the trauma his father, mother, and older brother struggled with while he was a child.

Woven through Nguyen’s personal story and family history is polemic on topics including America’s refugee crisis, George Floyd, the war in Ukraine, and what he calls “AMERICA.™”

Nguyen is no stranger to criticism for his political views. He told the audience he has been criticized by Americans as “anti-American,” by Vietnamese Americans as “communist,” and by the Vietnamese government as “anti-communist.” Most recently, he was scheduled to appear for an Oct. 20 reading at 92NY (formerly the 92nd Street Y) in New York City. The event was abruptly canceled, after Nguyen signed an open letter – along with nearly 700 other writers and artists – published in the London Review of Books calling for a ceasefire in Gaza.

Early in their conversation, Orange noted that Donald Trump’s name is redacted in The Man of Two Faces, appearing only as a black rectangle. In the audio book, his name is bleeped out.

“It’s a visceral experience as you listen,” Orange said. “You hear it as a sort of curse.”

The decision arose from Nguyen’s anger at Trump’s immigration and border policies, which separated children from their families. Nguyen’s son was 4 years old at the time, the same age as Nguyen when his family fled Vietnam.

The decision was also inspired by the amount of redaction found in documents – of which there are “quite a few,” Nguyen said – about conditions those children were kept in, the country’s border policy, and American foreign policy writ large.

“The American way of surviving all of that is to redact the realities and memories of what we have done and what we are doing,” he said.

The comment drew vigorous applause from the audience – who applauded after each of Nguyen’s answers. Orange – wearing a baseball cap, a signature look in his author appearances – quipped about the audience response.

Erudite and incisive, Nguyen was also funny. He prompted laughter as he recalled taking a college class with Maxine Hong Kingston, who gave him a B+ – which Nguyen called “the Asian F.” He said the first story he wrote, in the third grade, was titled Lester the Cat, and noted that The Sympathizer seemed to offend everyone – excepted the Pulitzer committee.

Most of The Man of Two Faces is narrated in the second person. Orange noted the narrative convention “is judged unfairly and underused in literature,” asking why Nguyen made the choice to use it.

The process of writing memoir, Nguyen answered, forced him to confront the conceptions he had of himself – as “ordinary,” “normal,” and “boring,” as American, while also a victim of American foreign policy, war, and racism.

“In order to write this memoir, I would have to figure out the self-deceptions I had engaged in my entire life,” Nguyen said.

One of the biggest ones came at a young age. Among the first movies Nguyen watched, when he was a preteen, was Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film about the Vietnam War.

By the time he saw it, Nguyen “thought of myself as an American.” But as he watched, “I felt myself split in two,” Nguyen said. “Was I the American doing the killing, or was I the Vietnamese being killed?”

He had no language to understand or answer that question. “I just put it away and I didn’t think about that again for many years,” Nguyen said. “I internalized those images I saw.”

The core of the memoir centers around Nguyen’s mother, who passed away in 2018. She was committed to psychiatric facilities twice during Nguyen’s childhood – first when he was a young boy, then when he was 18. His memories of the two events collapsed into one. He had no memory of his mother’s hospitalization as a small child, yet he felt “small and scared” when he visited her as an 18-year-old.

“I had deceived myself, or my memory had deceived me. I couldn’t trust my own memory,” Nguyen said.

“This man of two faces is me and myself,” he said. “I am talking to myself much of the time throughout the book.” (The phrase “man of two faces” also appears in the opening line of The Sympathizer and is one way the unnamed narrator refers to himself).

Nguyen writes about his family’s home in California standing on land that belonged to Native Americans. Orange commented that Nguyen’s book finds unexpected “common ground” between different marginalized or “othered” groups in America who experienced white supremacy and racism.

In response, Nguyen argued there is an implicit understanding that immigrants and refugees who come to the United States “are still better” than African Americans and Native Americans.

The success of immigrants and refugees, he said, serves as an “alibi of the American dream,” which he called a “euphemism for settler colonialism.”

Once that is acknowledged, “the ugliness that you’re talking about, we can start connecting it,” Nguyen said. Labeling people as “I’m Asian American, you’re Native American, you’re X, you’re Y, you’re Z,” which Nguyen called “your little DEI [diversity, equity, and inclusion] slot of inclusion,” is capable of creating more division and difference.

“I’m not about inclusion. I’m about solidarity,” Nguyen said. “I want to think past the politics of divide and conquer, and figure out the politics of unity and solidarity to actually realize freedom and democracy in this country.”

The comment drew the loudest applause of the event. Gesturing toward a corner of the audience, Orange said, to laughter, “there’s an extra-progressive pocket right here.”

Orange’s final question fused the talk’s themes of the personal and political, and concerned Nguyen’s use in the memoir of the word “re memory” or “re membered.”

“The book is largely a meditation on memory,” Orange said. “Could you talk about why you wanted to hammer in this idea of ‘re membering’?”

The choice, Nguyen answered, was inspired by Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which used the concept of “re membered” to show “the past is still with us.” Nguyen used the idea to think about the impact of racism, which makes racial minorities simultaneously “invisible” and “hyper visible.”

Speaking of Vietnamese Americans specifically, he said, “we’re seen and we’re seen through … we are subject to horrible stereotypes or killed on screen or raped on screen.”

To undo the effects of internalized racism, “self-hatred,” and “a sense of distortion,” Nguyen said, “we have to find a way to reconstitute ourselves holistically. We have to ‘re member’ ourselves.”