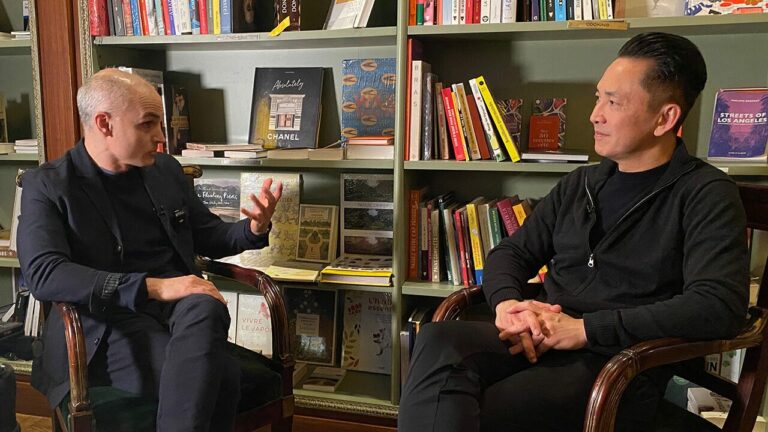

Viet Thanh Nguyen joins Michael Vann in a podcast to discuss his memoir, A Man of Two Faces for New Books Network

Speaker 1:

When it comes to personal style, it’s not just about having a signature look. There are layers to deciding what to wear. It could be all about bold patterns that stand out in a crowd, accentuating your gains, or finding something sleek yet comfortable. With Indochino, fall is the perfect time to add a few new layers to your wardrobe. They offer custom made-to-measure pieces at an off-the-rack price. And this season Indochino has new colors, fabrics, and styles to choose from. From classic suits for special occasions to head-turning outerwear for your sidewalk stride. Customize your new fall pieces however you want. Buttons, vents, pockets, lapels, you name it, they’ll build it. Just submit your measurements online or book a showroom appointment to work with an Indochino expert style guide in person. Add fresh layers to your fall style with Indochino. Go to indochino.com and use code podcast to get 10% off any purchase of $399 or more. That’s 10% off at I-N-D-O-C-H-I-N-O dot com, promo code podcast.

Speaker 2:

At Southern Careers Institute, we believe in the power of education to transform lives. With dedicated instructors, hands-on training, and a supportive community, our students discover their potential and unleash their ambitions. Whether you’re pursuing a career in healthcare, technology, or business, SCI provides the tools you need to excel. Visit scitexas.edu and apply today. Southern Careers Institute. Learn it. Do it. Live it.

Michael:

Welcome to the New Books Network.

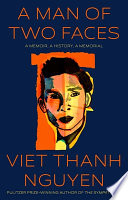

Okay. Three, two, one. Welcome to New Books In History, a channel on the New Books Network. I’m your host, Michael Vann of Sacramento State University, and today I’m chatting with Viet Thanh Nguyen about A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial, out with Grove Atlantic in 2023. Viet Thanh Nguyen is most famous for his novel, The Sympathizer, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and scores of other awards. His other books include Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and The Memory of War, a finalist for the National Book Award in Nonfiction and the National Book Critics Circle Award in general nonfiction, Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America, the bestselling short story collection, The Refugees, and The Committed, a sequel to The Sympathizer. He co-authored Chicken of the Sea, a children’s book, with his then six-year-old son Ellison. And HBO is turning The Sympathizer into a TV series directed by Park Chan-wook of Oldboy fame.

For a day job, he is the Aerol Arnold Chair of English and a professor of English American studies and ethnicity and comparative literature at the University of Southern California. And he has been the recipient of many fellowships, including the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundation Awards. But most importantly, this is the third time I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing him for New Books in History. Search through the back catalog to hear us talk about his novels, and I don’t know, I think arguably my favorite Viet Thanh Nguyen book, Nothing Ever Dies. I’m a big fan of that book, which I found so surprising and so enlightening in many ways. Dr. Viet Thanh Nguyen, Viet if I may, welcome to new books in history. Welcome back.

Viet:

[inaudible 00:03:16] Yeah, glad to be back here.

Michael:

Yeah. So, congratulations on all the success, and this newest book, which is a memoir, but so much more. And I was telling you off mic, I was really surprised at some of the directions it took, and found it really an emotional roller coaster in many ways, and just incredible. Normally at the beginning of the interviews, we ask the guests to explain who they are and how they came to write the book in question, but this is a memoir, right? That’s sort of the whole point of The Man of Two Faces. So, maybe we can just get right into it, and let me ask you, what brought you to writing a memoir at this point in your life? What did you want to reflect upon?

Viet:

I actually never wanted to write a memoir. It was an accidental book in a lot of ways, because I’d been publishing a lot of pieces in the New York Times, Time Magazine and so forth. My editor thought it would be great to put together a nonfiction book of these pieces. And I agreed to do it, signed the contract, got my advance, but it was soon pretty clear that I could not just simply put together a collection. I needed a narrative for this book. And what had been happening is that I’d been going around the country for six or seven years, giving a lot of lectures around things that concerned me, like Asian American issues or race or American politics, American history. And the way that I would give these lectures to audiences would be to narrate a story. And the narration increasingly became more and more autobiographical, talking about my parents, myself, our journey as refugees, how we came to the United States, and how we intersected with these kinds of issues. And I realized that that was the narrative of the book, that it would have to incorporate all these autobiographical instances.

And I think the real thing that I seized on was how, at one lecture, I was speaking about my parents’ grocery store, and what they had gone through as these refugee shopkeepers, and I was overwhelmed by emotion, and I thought I had put all of this behind me. And so it was something that I thought, since I’d been so seized by emotion, and I didn’t know why, I’d have to go back and investigate that. And that then was the roots of this book turning into something much more personal and a memoir.

Michael:

So it was drawn from many of these previously given lectures and published pieces, and then added onto it and sort of built up from there?

Viet:

Right. It was actually a really fun book to write in a lot of ways, because I was able to go back to my childhood, go back to all of these childhood memories and experiences that I hadn’t thought about in a long time, and to get to talk about things that had been deeply meaningful for me, obviously for personal reasons, but also because there were moments of intellectual and political and emotional awakening in San Jose, at Berkeley, as a writer, as an intellectual, and so on. And that was fun for about two thirds of the book, which I wrote really quickly, the first two thirds. And then the last third was getting to the part of memory that I had chosen not to remember, either deliberately or accidentally. And the last third took me much longer than the first two thirds of the book to write, and the last third deals much more with what happened to my mother, who went to the psychiatric hospital at least three times in her life in the United States, two of which I remember pretty well.

And it was something that I’d actually written about as a college student when I was 19 for Maxine Hong Kingston in a nonfiction essay, and then I’d put it away and not thought about it for 30 years, or rather, when I did think about it, I totally misremembered it. I thought that my mother had gone to the psychiatric hospital when I was a kid, when in fact, when I picked up that Maxine Hong Kingston essay again 30 years later, I discovered she had gone when I was about 18 years old. But it was so disturbing to me that I had, once I put that essay away, my memory literally changed the facts. And for years and years I thought, this had happened to me much earlier, because that’s how I felt, so vulnerable and frightened.

And so the book is also then not just about finishing this narrative that I began when I was 19, but was not artistically and emotionally capable of finishing until now, but it’s also a book about the nature of memory, how we remember, and how we forget, certainly as an individual in my case, but also as a culture and as a nation.

Michael:

Had you realized that you had misremembered and forgotten parts of your mother’s experience before or after you wrote Nothing Ever Dies, which is about the memory of war in Vietnam?

Viet:

Nothing Ever Dies was a transformative book for me, because I wrote that… Again, sort of the same process. I mean, I’d written a lot of academic essays after my first academic book, and these academic essays had to deal with Vietnam and the war and memory. And I was really trying to stop writing like an academic, which is how I wrote my first book, Race and Resistance. And I was taking all these experimental turns in the writing with these essays. But when it came time to writing Nothing Ever Dies, the book, I had just finished The Sympathizer, and had about a year off before the book tour began for The Sympathizer. And so I decided to write Nothing Ever Dies from scratch as a narrative, taking all the ideas from the essays, but just writing it as a book in and of itself.

And so it was a very narratively driven book, even though there are academic ideas and arguments and so forth. And because it was narratively driven, I incorporated a little bit of my autobiography of myself and my family in there, and gestured at my mother. So, that was really when I started to flex this particular kind of writing ability or writing muscle, and yes, started to think about things that had happened to my family, but also specifically my mother. But I really only barely scratched the surface at that point in Nothing Ever Dies. So, I don’t think I even realized that I had changed the actual facts of things, but I certainly realized how important my mother’s story was to my own, and that was why I began gesturing at that in nothing Ever Dies, which is a book about war and memory in terms of Vietnam and the United States and other countries, but also hinted at the importance of war and memory for me as a person.

Michael:

Right. And no spoiler alert to people who haven’t read your memoir, but the war in Vietnam obviously is the major force in shaping your family’s life, and particularly the traumatic violence of war in the early ’70s, and your parents being refugees twofold, fleeing from the communist north in 1954, and then fleeing in 1975. So, I find that so fascinating that you’ve done this book about war and memory in Vietnam. Meanwhile, you as an individual are still wrestling with your experiences around memory induced into your family’s life by the wars of Vietnam.

Viet:

I think my feeling is that, for many people who have lived through some kind of traumatic experience, war for example, it takes a long time to process that information. You look at certain American veterans of the war and their encounters with their own past, it takes them multiple books to try to attempt to work through what they experienced. And I think that’s similar for me. And one of the points that A Man of Two Faces makes is that how we as Americans, and maybe people all over the world, conceive of war stories is extremely limited. We think of war stories generally as things involving men and soldiers and battles and so on.

And one of the points of the book is, my parents’ stories are war stories, what they went through. They were never soldiers, but they were displaced as refugees twice, lost a lot, suffered a lot, witnessed a lot, arguably saw more than a lot of soldiers who never saw combat did, for example. And your average American soldier went to Vietnam for a year, and many of them, again, were guards at bases and things like this. Whereas every single refugee who has come to the United States from Southeast Asia has gone through something horrible by definition of being a refugee. And so the book really wants to assert the idea that the idea of war stories needs to be much more comprehensive, to account for everybody not included in the narration of combat and heroism and sacrifice.

And so I think for me to even grapple with that, it took more than one book. I started to deal with it in Race and Resistance when I talked about Le Ly Hayslip’s writings, for example. And then I wrote the short story collection The Refugees, and The Sympathizer, and then Nothing Ever Dies, and now this book. And each of them takes up the question of war and memory and other issues related to war and trauma from different angles, different fictional strategies, narrative strategies, foregrounding different kinds of theoretical and thematic elements that have been important to me.

Michael:

Yeah. And one of the things that comes out from the memoir is the post-war, the idea of the war never really being over. So, your parents as refugees made it to the United States, to Pennsylvania. There’s this trauma of separation early on where you and your brother are taken away from your parents and raised with foster families briefly, and then reunited. And then finally resettling in San Jose and creating this new life, following this “American dream” in opening up this Vietnamese market, yet they’re constantly dealing with the post-war, and specifically dealing with anti-Vietnamese sentiment in San Jose, and you talk about this with a sign that was put up. Was it at your parents’ store?

Viet:

So, the sign was nearby [inaudible 00:13:31].

Michael:

Nearby. Yeah.

Viet:

Yeah. And I think about how, in Nothing Ever Dies, I say something like how wars don’t end simply because we say they do. So, simply because there’s been a ceasefire or someone’s been defeated, and the historians say the war ended on April 30th, 1975, or pick whatever date for whichever war, for those who have survived a war, I don’t think wars end on those dates, and possibly never do end. So the idea of the post-war, it’s important in an official sense, but I don’t think the post-war ever really ends. I see that in terms of the impact on actual people I know, Vietnamese veterans of the war, for example, who are still deeply affected by this war, or by nation state politics. Joe Biden just visited Vietnam, and wow, is that an example of how the ongoing legacy of the war in Vietnam continues even in unspoken, muted ways in the relationship between Vietnam and the United States and China.

And so certainly in this time period that the memoir deals with, 1975, but very intensively in the 1980s and during my adolescence, the Vietnamese refugee community was deeply affected by the war in Vietnam. It was a living issue for them. It wasn’t even history. And certainly that was true for Americans who were working through the war in political speeches and in nonfiction books, and certainly in Hollywood, for example. And we as refugees were the living embodiment, in some ways, of the war for the Americans who encountered us or heard about us. And so, the majority of Americans didn’t want to accept refugees from Southeast Asia in 1975, for example.

And when we arrived in San Jose in 1978, and my parents opened their Vietnamese grocery store, our history as Vietnamese refugees from an American war intersected with these deep histories of anti-Asian exclusion and racism in the United States, and so we simply became the newest specter of Asian threat, economic and cultural competition to white Americans. And so that sign that was in a window near my parents’ store was another American driven out of business by the Vietnamese. And I encountered that when I was 10 or 12 years old.

And the fact of the matter was that, in downtown San Jose where my parents opened their business, it was a decaying downtown that the Vietnamese refugees came in and made better, because they opened all these Vietnamese businesses down there. So on the one hand, you could see it as revitalization. On the other hand, you could see it as a yellow peril threat, as this person did who put the sign in the window. And so that was one of my earliest exposures to the idea of anti-Asian racism, and it completely intersected with the history of the war that it brought us to downtown San Jose.

Michael:

Mm-hmm. So many things. I mean, one thing I noticed, the new history of Palo Alto, I’m forgetting the author’s name, but one of the points he makes is that many Southeast Asian refugees working in early Silicon Valley, manufacturing microchips and things, sometimes taking them home, are actually frequently making the hardware for weapons systems to be used in wars in Southeast Asia. And also, you mentioned Biden going to Vietnam recently. This book is a lot about memory, but a lot about forgetting. And one thing that I think has been forgotten recently is that Biden as a senator was stridently opposed to the resettlement of Vietnamese refugees in the United States in 1975. You talk a lot about Trump, whose name you won’t print in the book, it’s blacked out, but this is really a bipartisan anti-Asian sentiment, right?

Viet:

Absolutely. And one thing I want to stress here is that this book is deeply critical of a lot of things and wears its politics on its sleeve. I mean, the book is deeply critical of settler colonialism. It argues that the American dream is a euphemism for settler colonialism. I’m sure that’s going to make a lot of people happy. And so, it’s not a Democratic book. Again, if we look at the United States, part of the problem is, we tend to separate in the United States the domestic discussion from the international discussion. So we get partisan about the domestic issues in the United States as liberals versus conservatives, on issues of race, for example, and racial discrimination, et cetera. But these things are inseparable from the international dimension of American foreign policy and the military-industrial complex and American wars overseas. That I think makes a lot of Americans uncomfortable to try to make that connection.

And so, when it comes to foreign wars and American attitudes towards remembering those wars, it is a bipartisan consensus that, number one, the U.S. deserves to rule the world. We’re the greatest country on Earth, because we have the greatest military-industrial complex of the world, and the wars that we wage are justified. And Democrats and Republicans are unified, in general, certainly in the presidents, to try to narrate the war in Vietnam as a failed but ultimately noble endeavor. And Biden is no different. And in fact, the way that Biden oversaw the American withdrawal from Afghanistan and his attitude towards the Afghans, I think pretty much seems consistent with his attitudes towards Southeast Asian refugees. And so the book tries to hold Americans in general accountable for their foreign policy and overseas actions and attitudes, from the very origins of this country, but when it comes to Asia, certainly through the Philippines, Korea, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and then to Greater Asia in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Michael:

Yeah. In the last third of the book, you have this section, I won’t read the whole paragraph, but it talks about when you’re at Berkeley and you start to learn an un-whitewashed history, and you say, it wasn’t you that were whitewashed, it was America that was whitewashed in its historical representation, and the editing and sanitizing of the wars of conquest that brought Asians and Pacific Islanders to the mainland of the United States. And you conclude saying, “Asians have never invaded America. It’s America that has invaded Asia.” And this sort of ties that yellow peril, Asian invasion hysteria and flips it and says, “The invasion is the United States.” Right?

Viet:

Absolutely. And there’s an anecdote I recount in the book about how in my high school, which was a primarily white high school, there were some of us who were of Asian descent, and we had no language for ourselves. So, we would gather in a corner of the campus and call ourselves the Asian invasion. And that was our self-referential, gently self-mocking labeling. We didn’t even know how to call ourselves Asian Americans back then.

But the point of the anecdote is that the power of propaganda and ideology is so strong that even a term like Asian invasion that we internalized is a manifestation of this idea, naturalized idea, that the United States is under threat by all kinds of forces, including Asians and the yellow peril. But in fact, it’s usually the United States going elsewhere, bombing in other countries and taking it as our right to violate other countries’ sovereignty and aerospace and things like that. And so, I think we as Americans absorb this narrative and political assumption of our place in the world, again, as the dominant power and force that is our God-given right. And it’s really, really hard, I think, for Americans on the average to try to overcome that narrative and to see their country from the outside, not as a country under threat by invading forces of various kinds, but also a country that is itself the invader in a lot of contexts.

Michael:

Mm-hmm. And again, something that is frequently forgotten about in the teaching of history and in popular historical memory. Not my classes, let me tell you. I’m one of the good ones, trust me. But just a minute ago you said that the book’s not a Democratic book, and I think you meant big D, right?

Viet:

Yeah. Big D. Yes.

Michael:

Not aligned with the Democratic Party. So, let’s get into politics. In the book you identify your politics as Marxist, but Groucho Marxist. And we’ve been talking about some really gut-wrenching issues, and especially the last third of the book is very emotionally powerful, but the book is also very delightful, and you are having fun. Could you talk about your discussion of Groucho Marxism and what that means to you in terms of a political sensibility?

Viet:

Yeah, I think the book is fun. Like I said, it was very fun for me to write the first two thirds, and there are a lot of jokes and so on and so forth in the book, and a general narrative tone of I hope scathing satire pervades the work. And I felt that it was very important for me to do this, because there’s obviously a lot of memoirs, a lot of histories out there that take a very serious approach to the very serious history that I deal with, and absolutely so. But there should be room for us to have fun as well, fun in a very meaningful sense, fun certainly to alleviate the pressure on the writer and the reader, but also fun in the sense of satire and using humor as critique, because these are important narrative and political tools that are manifest in my novels, like The Sympathizer and The Committed, for example.

And here in this book, I felt that part of what it means to be a refugee in this country, it’s not only to suffer feelings of tragedy and melancholy and all of that, but also to recognize the absurdity of our situation and the hypocrisy that has brought us here. Not just the hypocrisy of the United States, although that’s very important, but the hypocrisy of all the powers that have been present in Vietnam. From the French and the Chinese to the Vietnamese, everybody’s been corrupted by their own ideologies and their own pretenses.

And so when I say Marxism, I’m pretty serious in saying that I am a Marxist in the Karl [inaudible 00:24:23] Marxist sense, but only if we understand that the dialectic is between Karl Marxism and Groucho Marxism. I think both would benefit from each other. The Karl Marxists typically don’t have a sense of humor or self-awareness or irony, and that leads to terrible consequences. And then the Groucho Marxists are very funny, but if they were also Karl Marxists and have a class consciousness, they’d be even funnier, in my opinion. And so it’s that intersection between the two that becomes very important for me to do both at the same time, carry out a critique that is very cognizant of imperialism and warmongering and racism and so on, but a critique that’s also very scathing and funny at the same time.

Michael:

Mm-hmm. And the book tells the portrait of the artist as a young man, or at one point you say portrait of the artist as a young fathead, and you’re coming to political consciousness, radicalized at Berkeley, of course, time in Maxine Hong Kingston’s class, and as a student activist getting arrested. Fast-forward a couple decades, and you’ve made it. Right? You have a prominent chair at an elite private university in Southern California, a Pulitzer, Guggenheim, Genius Award. And you have this vignette in the book about finding yourself in the Ronald Reagan Room at this elite social club in Southern California. Could you talk about that, and reflect on your relationship to power? What’s it like to be the rebel who gets into these halls of power?

Viet:

Yeah. I talk about how, when I was an undergraduate at Berkeley, so for example in Maxine Hong Kingston’s class, she has told me that I was the worst student in her class. She’d give me B+, which is the Asian F. And when I was an activist… And my excuse to myself was, the reason I’m falling asleep every day in Maxine Hong Kingston’s class is because I’m so busy being an activist. Well, one of the things I was doing was storming the offices of the president and storming the faculty club and swearing to myself, “I will never join clubs like this.” And then of course, eventually was invited back to speak at the faculty club at Berkeley, and invited to speak at these extremely expensive private clubs in L.A. that I never even knew existed. And I have no desire to actually belong to these clubs. I mean, at least one of them offered me an invitation to apply, and I was like, “I’m glad you think I make that much money, but I don’t.”

Michael:

Also, you have a Groucho Marxist sensibility here, right? About clubs.

Viet:

Of course. I wouldn’t want to belong to any club that would have me. But I often accept, not always, but often accept these invitations to speak at very elite and exclusive spaces of capitalistic nationalist militaristic power, because I want to see what’s going on. Because, number one, I believe that the people who run these things are human beings. They’re not just faceless embodiments of the state or capital and so on, but they’re human beings. And as a writer, I want to know what they’re like and know their complexities. But also I just want to see what happens in these places. So, who knew when I went to this elite club that they would have all these paintings of great white men on their walls, including Clint Eastwood? I mean, that was interesting, that Clint Eastwood was right up there along with the presidents, for example, and the astronauts. Those kinds of details I just would not have realized until I’d been there.

Or that when I went there to one of these clubs to do a fundraiser for Harvard, I was the youngest person in the room, the only Asian, I was sat next to the oldest person in the room I’m pretty sure, he was about 97, 98 years old back then, very wealthy man who had flown bombers in the Pacific. And didn’t even look at me, but all of a sudden just announced to the table that it was justified that the U.S. had dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. I was like, “What occasioned this comment, except possibly me sitting next to him?”

So, that’s what it’s like to try to enter these halls of power to see what’s going on. And you mentioned all the awards, et cetera, that I’ve been lucky to get. And some people would say, “Well, you should be grateful. You’ve come to the United States, you’ve achieved the American dream. It wouldn’t have been possible except for us, great America. You should be grateful for everything you’ve got.” I am grateful for everything I’ve got. But as I say in The Sympathizer, maybe I wouldn’t need to be grateful for being rescued if we hadn’t been invaded in the first place.

And so, the book is about the complexities of that, that typically the narratives of the American dream demand total amnesia or selective memory on the part of the immigrant or the refugee or the newcomer to the United States. Forget what happened in your old country that we might’ve been involved with as Americans, or if you do remember, make sure you remember it as a narrative of American salvation, and then be grateful to the United States. That’s non-dialectical. To be a Karl Marxist/Groucho Marxist is to recognize the absurdities of a refugee winning the Pulitzer Prize or the MacArthur or Guggenheim or whatever, and then being trapped into silence because of his own gratitude. So, that’s not possible for me. I can be grateful, but I can be critical at the same time. That’s a part of the dialectic too.

Speaker 2:

At Southern Careers Institute, we believe in the power of education to transform lives. With dedicated instructors, hands-on training, and a supportive community, our students discover their potential and unleash their ambitions. Whether you’re pursuing a career in healthcare, technology, or business, SCI provides the tools you need to excel. Visit scitexas.edu and apply today. Southern Careers Institute. Learn it, do it, live it.

Michael:

Yeah. Talking about the inability of Americans to understand the dialectic, especially about the wars in Vietnam, makes me think of the history of the Vietnamese who resettled in, I think East Texas or Louisiana, as shrimpers, and they started working the bayou or whatever it is, wherever they pull shrimp out, which looks a lot like the Mekong Delta, and they got into conflict with white shrimpers. And the Klan went down there, and a lot of these guys that started fighting against these Vietnamese shrimpers over very real material things, like access to the shrimp fields or whatever they are, the fisheries, they’re Vietnam vets, American vets of the war. And they’re articulating racist and anti-communist rhetoric against these Vietnamese refugees who have fled the communist regime in 1975. And that complete inability of Americans to understand the nuances of history that they made, right?

Viet:

Yeah. And the irony, of course, is that none of this is new. For example, Asian American soldiers served in the American military during the war in Vietnam, and you hear stories from some of them about how they were used, not as target practice, but examples in training camp and in Vietnam, as what the enemy looked like. So, the behavior of the American fishermen… [inaudible 00:31:57]

Michael:

Ignoring the fact that they’re Japanese American or Chinese American.

Viet:

Right. So, the attitudes of the American fishermen are absolutely no surprise at all. And it speaks to the fact that these Vietnamese refugees should have been seen as allies of the United States. They were. They were allies of the United States, or they were forced to be allies of the United States officially. But at the level of practice, they or we would always be no more than the little brown brothers, as the Filipinos were more than a century ago. So, allyship for the United States in regards to people from non-white countries has always been a function of paternal benevolence, which is itself deeply racist.

Michael:

Mm-hmm. And what you were saying a few minutes ago made me think of something that you wrote when you invoke Aimé Césaire and James Baldwin, if I could just read the short section. You write, “Part of me believes what Aimé Césaire wrote in 1955. ‘The hour of the barbarian is at hand, the modern barbarian, the American hour. Violence, excess, waste, mercantilism, bluff, gregariousness, stupidity, vulgarity, and disorder.'” And then you write, “It has been a long hour, but part of me also believes what James Baldwin wrote that same year. ‘I love America more than any country in the world. And exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.'” And then you then write, “[inaudible 00:33:32] your parents never criticized this country.” Could you reflect on that, why you invoke Aimé Césaire and James Baldwin in this contrast?

Viet:

Well, my parents too [inaudible 00:33:43] they were not political people, my parents, except that they were deeply anti-communist because of their Catholicism. But other than that, they stayed out of politics. And I don’t know if they ever said they were grateful to the United States. They were grateful to God. That’s who they said we should be grateful to for where we happen to be in the world. But they were not critical of the United States, or they never said anything like that in my presence. And so, it’s up to me and maybe to people generally from the 1.5 and second generation, to be more critical of the United States, because my parents did not feel like they were Americans. Even though they became American citizens, they felt themselves to be Vietnamese.

Whereas people like me, we feel this is our country, the United States. And so therefore, we as citizens, and for some of us who were born in this country, we have the right to be as critical of the United States as anyone else who is an American. And I quoted Césaire and Baldwin because they present two interesting contrasts as Black intellectuals. Baldwin as an African American intellectual who then became an expatriate in Paris, and died in… I believe he died in France. Or is that the case? I’m trying to remember [inaudible 00:34:58] in the south of France, and [inaudible 00:35:00] find out more about that. But he chose to exile himself for a while from the United States.

And Césaire was a part of the global Black diaspora, both very critical of the United States and various versions of French and American imperialism, but Césaire as being someone who was not an American was able to be, in some ways, unreservedly critical of the United States. Not to say that Baldwin wasn’t critical of the United States, but Baldwin still had to inflect his criticism in that passage by confessing a love for America. And I think a lot of people who are Americans have a very hard time getting over that attachment to the United States. It is our country. We have deep effective bonds here. We have been shaped by the image of America that the United States has broadcast to its own people and to the rest of the world. Someone like Césaire, whether or not he was ever affected by that, refused in the end to have any part of that American ideology. So I wanted that contrast there, not to just invoke one or the other, but to show these differing responses to the American image.

Michael:

Mm-hmm. So when you’re writing this book, we just talked about Cesar and Baldwin, mentioned Maxine Hong Kingston, who were some of your influences in writing this book?

Viet:

Oh, there are so many. When I was writing this book, I had such a long list of poets and essayists and nonfiction writers that I was trying to invoke or pull ideas from. And I was thinking about how, in writing this book, the reason why I resisted trying to call it simply a memoir, and the subtitle is, “A Memoir, A History, A Memorial,” and the reason I resisted a memoir in and of itself is that the idea of a memoir, at least formally, brings forth for many readers I think the idea that it should look a certain way. There should be blocks of paragraphs and quotation marks and a linear narration, and this book does almost none of that.

And the reason why is this. I wrote the book very intuitively, as I wrote Nothing Ever Dies very intuitively, I gave in to my feelings in writing this book. And in that sense, the reason why I did that is because I wanted the form of the book that sprang out of me to be an expression of the content. Now, the content of the book is about how history really messes us up, those of us who are refugees, our lives are blown apart, rendered into fragments. Our memories are destroyed and rendered into fragments. And so then the act of doing something like a conventional memoir that would put a linear narration and make everything very cohesive, to me is an act of fiction, ironically, in a book that would purport to be nonfiction.

So, a nonfiction work that would be true to my experiences and my memories and so on would formally be rather fragmented, and it would look that way on the page. And so, I think this book is actually very easy to read, and so many people have told me, but it does look different, because it uses willfully, whenever it wants to, right justification versus left justification. It has parts that look like poetry, it has parts where the typography suddenly expands or shrinks and so on. And so I was influenced by writers who had been experimental, because they had been shaped by history, that for example the borders of their communities had been overrun by the forces of history, by invaders and colonizers and so on. People like Gloria Anzaldúa in Borderlands/La Frontera, for example, or Don Mee Choi in DMZ Colony, or Claudia Rankine in Citizen and American Lyric, Mai Der Vang in Yellow Rain.

And I’m citing people who are poets, who are nonfiction writers, who blur the lines as Rankine does, as Don Mee Choi does, as Gloria Anzaldúa does. They blur the lines because colonization and invasion have already blurred the lines. And so I think when writers respond by saying, “We’re going to do whatever we want, we’re going to blur the lines of genre, we’re going to blur the lines of form,” it’s not just an artistic experiment for art’s sake. It is a formal response to the historical realities of rupture, division, invasion, colonization, appropriation, and so on.

So, that’s the artistic intellectual answer I’m giving you. But really what it all boils down to when I was writing the book was, why not? Why can’t I do this? Why can’t I do that? There’s a very willful, playful, childlike impulse in writing this book, and it came out of the fact that I’m a father. I can see my children always implicitly asking the question, why not? Why can’t I do this? Why is there this boundary or that border? And they do beautiful fun things as a result, that we as parents may be sometimes irritated by, but oftentimes, in my case at least, struck by wonder and joy at what they’re able to accomplish.

Michael:

It’s how they learn. It’s how they learn.

Viet:

[inaudible 00:40:24] And so the book is very serious in a lot of ways, but it’s also, again, very childlike and very joyful and very funny in a lot of other ways. And all you as a reader have to do is just go into the book and give in. Don’t come in and say, “Oh gosh, there’s no quotation marks. Oh gosh, why is stuff right justified? Oh gosh, why does there appear to be what looks like poetry or stanzas in here?” Just don’t care and just read, just fall into the words, and I promise you, you’ll be swept away to the very end before you know it.

Michael:

I will co-sign that. I was swept away. It reminded me of something you did in I think The Committed, where the words start to literally take off from the page. And also Safran Foer. I don’t know if it was his first novel with Everything Is Illuminated, or the second one about 9/11, there’s a similar thing where the words start to fly around the page, and it makes you really wonder, can you control this novel? Can you control this memoir that I’m reading?

Could I ask you to say a few words on language? And if I recall this right, you write that when you were younger, you were worried about not being proficient in both English and Vietnamese, so you made a conscious choice to embrace English at the expense of tiếng Việt, Vietnamese language. Now, with the Pulitzer Prize on your shelf, I think it’s safe to say that you are a master of the English language and an acclaimed author. But in A Man of Two Faces, you keep reflecting on your mother’s weaker command of the English language, and I think you note that your father had not read The Sympathizer when you won the Pulitzer. And you also allude to your struggles with Vietnamese, and there’s a bit of a very interesting reveal at the end with the Vietnamese that you learned at home. Could I ask you to reflect on your experience with language and identity and what it means in this book?

Viet:

Absolutely. Very, very important to me, this question of language and identity. And as with many other Vietnamese refugee kids, I grew up with a conflicted relationship to the Vietnamese language. I [inaudible 00:42:35] came at four, and I like to say that I was fluent in Vietnamese at the age of four when I came, and I’m still fluent in Vietnamese now, at the age of four.

Michael:

As a four-year-old?

Viet:

Yes. It’s a slight exaggeration. In fact, I took it seriously enough so that I went back to Vietnam for seven months and studied formal Vietnamese at Vietnam National University. If by formally studying Vietnamese, you mean going to a bar and drinking lots of beer, that’s what I did every night to practice my Vietnamese. But I mean, it’s a very conflicted relationship to the Vietnamese language that I have, because language becomes the sign or set of signs of authenticity, of belonging, of love, emotion, and also of negative things like shame, for example. I experienced all those emotions through the Vietnamese language.

And I like to think of myself as being whitewashed ahead of my time, because in the 1980s, most Vietnamese kids my age knew a lot more Vietnamese than I did. And when I went to college and joined the Vietnamese Student Association, the meetings were actually often conducted in Vietnamese. But now I recently went to my university’s VSA, and it’s completely in English, and Vietnamese is only used briefly, even though a third of the students are actually international students from Vietnam. There’s been a total sea change in the relationship of Vietnamese Americans to the Vietnamese language and notions of authenticity. But back then, in the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, if you didn’t speak Vietnamese, you were not really Vietnamese.

And so I knew that, and yet at the same time, I could not make myself study Vietnamese with any devotion. My parents sent me to Vietnamese Catholic Sunday school, which was the quickest way to guarantee I would never learn Vietnamese. They hired people to teach me Vietnamese, and these people used the Bible. Another way I was never going to learn Vietnamese. And so I knew that if I did not keep up my Vietnamese and learn it, I would grow distant from my parents. I could see it happening in real time. And yet, I couldn’t will myself to study Vietnamese with any seriousness until I was well into my early thirties.

And what happened as a kid was, I’m pretty sure I subconsciously, and then very consciously, made this decision that I was going to, as you say, and as I say, master English, because that was the route to belonging in this country. And so again, I thought, I could be bad in both languages. I could be good in Vietnamese and poor in English, or I could be great in English and poor in Vietnamese. Those were my three choices, and I chose the last one, because I felt like I had to belong to this country.

And then through that, and especially through the act of writing fiction, I could not only belong to this country, but I could own this country. This was my way of fighting to belong. There’s so many things that are problematic about what I just said, because nowadays I would [inaudible 00:45:30] this idea that anyone can master a language. I don’t think I’ve mastered English. I just did the Audible recording for this book, and there were moments where I was like, I can’t even say the word iron, for example, or the sound engineer would say, “That’s not how you pronounce insidious.” [inaudible 00:45:45]

Michael:

Yeah. I think the Pulitzer Prize Committee would disagree [inaudible 00:45:49] with all due respect, come on.

Viet:

Right. [inaudible 00:45:51] But it’s not mastery, right? It’s not mastery. And the very idea of mastery, of ownership, of belonging, all these things [inaudible 00:45:58] invested in, in my teens and twenties and even further, are deeply problematic terms, both in terms of our relationship to a language, but our relationship to the United States. And I think immigrants are lured with this idea that you can master English and therefore master being an American. You can own the country and belong to it, with all of the problematic implicit baggage of settler colonialism and being inheritors of genocide and enslavement that that entails.

And the book grapples with all of that, too. What does it mean to arrive as a Vietnamese refugee on settled land? We came to Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, something I didn’t think about for 40 years, but it’s totally problematic. And so the book is an encounter with trying to grapple with the mastery of America and the language, and then unsettling all of these efforts at settling in this country.

Michael:

Yeah. And we don’t have time to get into it, I want to be respectful of your time, but one thing as a historian of Vietnam that I appreciate is that you critique American settler colonialism, yet you also note that Vietnamese history is a history of settler colonialism. And the town where you were born was a settler town, where ethnic Vietnamese were living up in the highlands. But that’s a conversation for another time, but including that complexity in there, I greatly appreciate it. Can I ask you who you write for? Or maybe you don’t write for anyone. But who do you write for?

Viet:

I think ever since The Sympathizer, I can honestly say I write for myself first [inaudible 00:47:40] foremost.

Michael:

In the book, you’re addressing yourself for most of it.

Viet:

Right. Yeah. And The Sympathizer was written purely for myself, and I created a man of two faces and two minds as the protagonist, who was a mask for me. I mean, I’m not him, but many of the ideas and emotions he experienced were mine. And in this book, A Man of Two Faces, I felt that the only way I could really write this book, because it was so personal and so intimate, was to create some distance from myself. And so I pretended that I was The Sympathizer writing this memoir of myself. That’s partly why it’s called A Man of Two Faces. And much of the book is structured as a dialogue between me and myself in the narration.

So, the first audience is myself, because I think that I have certain kinds of convictions, political and artistic and personal, that I have to be true to. And so my first reader has to be me, as a judge of my own work. But then after that, it gradually expands. And so yes, in the book, there’s a very deliberate address to Vietnamese Americans, and it’s an echo of Maxine Hong Kingston who, on page five of The Woman Warrior says, “Chinese Americans.” She’s explicitly talking to Chinese Americans. And I think those of us who are so-called minority writers, we have to be very self-conscious about who our audience is, because if we are not, it’s so easy to fall into the assumption that is so deeply held by so many people that our audience has to be white people. And I think even for a lot of non-white people, we’ve internalized that so much, we [inaudible 00:49:15] even know we’re talking first and foremost to white people.

So, I think you just have to be very explicit, at least to yourself, about who your audience is. And my first audience after myself and after my wife is Vietnamese Americans, and then it’s Asian Americans, and then it’s Americans, and it’s the whole world. Because as a writer, I feel myself to be a writer of all these communities. I’m a writer just for my own sake and in the broad sense, but I’m a Vietnamese American writer, an Asian American writer, an international writer. In France, I’m classified in one bookstore as an Anglo-Saxon writer. In other contexts, I’m introduced as an American writer when I’m overseas. All of these identities and communities and audiences are important to me.

Michael:

Mm-hmm. And you recount how at one point someone, I think it was a prominent scholar, asked about your work being translated into English.

Viet:

I don’t know if that was a prominent scholar. That was an editor whose name I [inaudible 00:50:12] came out.

Michael:

Oh, the editor. Okay.

Viet:

This person had certainly heard of it, and he was just making small talk, or emailed me, I don’t know what it was, and said, “So, what’s it like being translated into English?” And I was like, “Oh my God.” It’s one of many little indignities that are hardly unusual for writers of color in the United States.

Michael:

Yeah. Yeah. I could talk to you forever, but we need to be respectful of your time. Two questions before I let you go. These are the standard New Books debriefing questions. Can you suggest two books for the audience? Things that you love.

Viet:

From the entire bibliography of the world to recommend to the audience?

Michael:

Things that you, just off the top of your head, you want people to read.

Viet:

That’s such a hard question. It’s actually one of the questions I hate the most, is… [inaudible 00:51:06]

Michael:

Is it really?

Viet:

Yeah, because my mind just automatically goes blank. And what I’m going to do is I’m going to pull up my Excel sheet of books that I have read, Michael, and you can ask me the next question while I look at the Excel sheet to remind myself [inaudible 00:51:20] that I’ve read recently that I have not [inaudible 00:51:22].

Michael:

The next question, and the standard question we always ask at the end is, what are you working on now, and what can we hope to see from you next?

Viet:

I’m giving six lectures at Harvard called The Norton Lectures, and I have to actually turn those lectures into a book. So, that’s [inaudible 00:51:39] I’m desperately trying to write these lectures before I give them. And so, that’s been preoccupying me. And then after that, then I hope I will get around to writing the third and final novel of the Sympathizer trilogy. And one other thing, I finished a children’s book with the artist Minnie Phan called Simone that’s coming out in May of 2024, about a Vietnamese American girl confronting wildfires in California. That was a lot of [inaudible 00:52:06] to do.

And now to get to your previous question about books I recommend, well, there are so many, but let me just cite two radically different works. [inaudible 00:52:17] I’m really trying to read all the Norton lectures that I can, so I had a lot of fun reading Jorge Luis Borges’s This Craft of Verse, his Norton Lectures. I felt that I learned so much from that book. And then I also had a lot of fun reading Fae Myenne Ng’s Orphan Bachelors, which is her memoir, and she had written a novel, her first novel Bone in the early ’90s, about second generation Chinese Americans and their immigrant parents in Chinatown, that had just blown me away. And she’s had this lifelong career project of working on the issue of Chinese immigrants and Chinese Americans, and Orphan Bachelors is her memoir of growing up in San Francisco Chinatown as the daughter of these Chinese immigrants.

And in many ways, it’s related to A Man of Two Faces, because she’s grappling with what it means to be Chinese, American, and immigrant, but also what is the very nature of this country that would do something like the Chinese Exclusion Act, and by extension, the creation of an entire orphaned bachelor Chinese immigrant male community in this country?

Michael:

Mm-hmm. Fantastic. Yeah. I also remember a couple of years ago you tweeted out, I forget the author’s name, but the novel is Interior Chinatown.

Viet:

Charles Yu. Yes. Very, very funny book that Charles is turning into a TV series.

Michael:

Oh, awesome. You tweeted that out and I read it, and I love that book. So that’s a…

Viet:

Yeah. [inaudible 00:53:45] are reliable.

Michael:

Okay. Thank you so much for talking with me today. I really appreciate you taking the time for this.

Viet:

Thanks so much, Michael. It’s always fun.

Michael:

Okay. So, this has been a conversation with a Viet Thanh Nguyen about A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial, out with Grove Atlantic in 2023. I’m Michael Vann of Sacramento State University, and this has been an episode of New Books in History, a channel of the New Books Network. Thank you for listening.

With insight, humor, formal invention, and lyricism, in A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2023), Viet Thanh Nguyen rewinds the film of his own life. He expands the genre of personal memoir by acknowledging larger stories of refugeehood, colonization, and ideas about Vietnam and America, writing with his trademark sardonic wit and incisive analysis, as well as a deep emotional openness about his life as a father and a son. At the age of four, Nguyen and his family fled his hometown of Ban Mê Thuột to become refugees in the USA. After being removed from his brother and parents and homed with a family on his own, Nguyen is later allowed to resettle into his own family in suburban San José. But there is violence hidden behind the sunny façade of what he calls AMERICA™. One Christmas Eve, when Nguyen is nine, while watching cartoons at home, he learns that his parents have been shot while working at their grocery store, the Sài Gòn Mới. As a teenager, films about the American War in Vietnam such as Apocalypse Now threw him into an existential crisis: how can he be both American and Vietnamese, both the killer and the person being killed? As his parents age, he worries increasingly about their comfort and care, and realizes that some of their older wounds are reopening. Profound in its emotions and brilliant in its thinking about cultural power, A Man of Two Faces explores the necessity of both forgetting and of memory in the life story of one of the most original and important writers working today.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is most famous for his novel The Sympathizer which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and scores of other awards. His other books include Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (a finalist for the National Book Award in nonfiction and the National Book Critics Circle Award in General Nonfiction), Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America, the bestselling short story collection The Refugees, and The Committed, a sequel The Sympathizer. He co-authored Chicken of the Sea, a children’s book, with his then six-year-old son, Ellison. HBO is turning The Sympathizer into a TV series directed by Park Chan-wook of Oldboy fame. For a day-job, Dr. Nguyen is the Aerol Arnold Chair of English and a Professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. Dr. Nguyen has been the recipient of many fellowships including the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundations. But most importantly, this is the third time I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing him for the New Books Network. Search through the back catalog to hear us talk about his novels and, my favorite Viet Thanh Nguyen Book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War.

Michael G. Vann is a professor of world history at California State University, Sacramento. A specialist in imperialism and the Cold War in Southeast Asia, he is the author of The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empires, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (Oxford University Press, 2018). When he’s not reading or talking about new books with smart people, Mike can be found surfing in Santa Cruz, California.