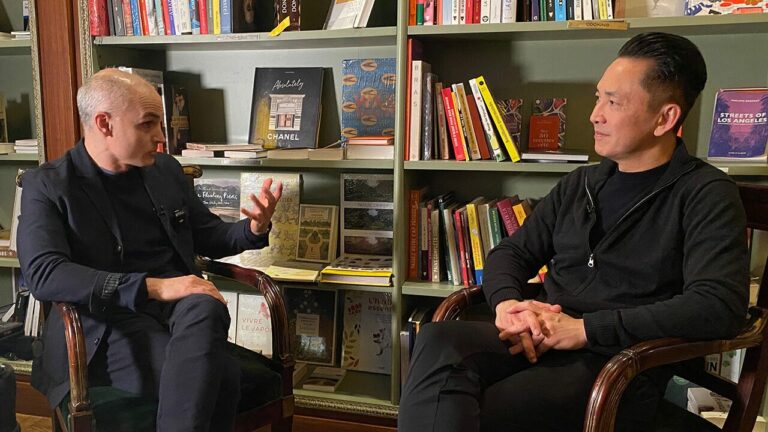

Nguyen joined host Kerri Miller on stage at the Fitzgerald Theater for the third conversation in the 2023 Talking Volumes season. Their discussion was candid and eloquent, poignant and funny, as they talked and shared photos from Nguyen’s new memoir, “A Man of Two Face,” for MPR News

Viet Thanh Nguyen has a critical mind.

He’s critic of populist politics. He’s a critic of history. He’s a critic of the country where he was born, Vietnam, and he’s a critic of the country he calls home, the United States. He’s even a critic of his own memories.

But Nguyen says his captious lens isn’t meant to blister. It’s simply meant to reveal truth. And if you write truthfully, you will likely offend.

Kelly:

Good evening everyone. Thank you for coming out on this night. Welcome to Talking Volumes. It’s so good to see you here, especially since it is rainy. My name is Kelly Gordon. I’m a producer at MPR News. I’m actually one half of the team that brings you book coverage, including Big Books and Bold Ideas every Friday. The other half, of course, being our host Kerri Miller.

I just wanted to come out and give you a few quick notes before we get started, but it will just take a second. So I wanted to let you know that after tonight we have one more Talking Volumes event in the 2023 season. It’s Margaret Rankle, she’ll be talking about her book, the Comfort of Crows. That’s next week. And we still have tickets available. So if you don’t have your tickets yet, go online, get them. We would love to see you next week to close out the season.

Of course, we’d like to send a big thanks tonight to our Talking Volumes season sponsors, Becker Furniture World and Great River Greening for their support in all things books. You can clap. I feel like there’s people who are like, I don’t want to Minnesota-nice this. And in fact, Great River Greening is in the lobby tonight handing out bookmarks, so be sure to go out and say hi to them and tell them thank you for all their support, what they do here in making this possible.

I wanted to give out a shout-out to, is there a group of students here from Luther College? There they are. You guys are so quiet. Thank you for coming. Luther is one of our educational sponsors. We appreciate you coming out and avoiding your homework. This is the best way to do it. A note too, that we are going to have an in-person book signing after the event. So if you are interested in that, once we get done, you can line up over here in this aisle and we will have an usher bring you up on stage when the time is right and you can get your book signed by Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Also, finally, last but not least, right, we wouldn’t be able to do any of this without our partner, the Star Tribune, and we have Zoe Jackson here tonight. Come on out Zoe. She is a race and immigration reporter of the paper. We’re so glad you’re here. Tell us a little bit about what’s coming up at the Star Tribune.

Zoe:

So we love collaborating with MPR on Talking Volumes at the Star Tribune. I had the immense honor of interviewing Viet earlier this year. He was kind and gracious, both about his writing and about the Twin Cities, which he gave a pretty good review, remarking that if you had to live somewhere in the Midwest, Minneapolis would rank very high.

So I just encourage you all to keep doing whatever it is you’re doing so Viet keeps coming back. You can find more books coverage from the Star Tribune online and in print. This Sunday’s books pages include a roundup of new horror novels just in time for Halloween, a review of the new Alice McDermott novel and a review of a book called Blood Ties, which is a mystery about missing and murdered indigenous women. So we have all sorts of stuff. Thank you so much for coming out.

Kelly:

Yeah, thanks Zoe.

Zoe:

Thank you.

Kelly:

Yes, of course. And with that, let’s get our evening started. I’m happy to welcome Kerri Miller to the Talking Volume stage.

Kerri:

Thank you, Kel. Hello, survivors of the monsoon. Oh my gosh, I don’t know. It never seems to fail that at least at one or two Talking Volumes, we get these torrential rains or snow. So I’m really happy you’re here and you made it out here.

If you were here for my Talking Volumes conversation a few weeks ago with Anne Patchett, and who wasn’t, really? You remember that we talked about how we inaccurately think of memory as indelible. I remember it, so it must have happened. The narrator in Anne Patchett’s novel says, “There is no explaining this simple truth about life. You will forget much of it.” That’s one of the ideas that our guest has explored in his fiction and essays and is now wrestling with in his new memoir that pull the tension between forgetting and remembering. The idea that we are shaped by things that we don’t remember, by experiences that we never had.

So in pursuit of these answers, we’re doing something a little different tonight. In fact, we’ve never done this before. As our conversation begins, the audience here at the Fitz will see photographs on a screen behind us and Viet Thanh Nguyen has shared them with us from his family albums, his family collection. And since we know that there will be a listening audience, we’ll do our best to describe the photographs in detail. You can also see the whole interview and the pictures on YouTube.

So let’s get started. Viet Thanh Nguyen’s new memoir is titled A Man of Two Faces, A Memoir, A History, A Memorial. He has never been on the stage of the Fitzgerald Theater. Can you believe that? Please give him the warmest of welcomes. Why haven’t you been to Talking Volumes before? What?

Viet:

I have no idea, but better late than never. And Kerri, it’s always such a pleasure to talk to you.

Kerri:

And you too. Thank you so much for coming. I want to say something real quick, Viet, about the photographs that we’re going to see through the interview. They come from your family collection, your parents, some of them are older than that. Tell us a little bit about this collection of photographs that has been passed down to you.

Viet:

Sure. My father was the family photographer. In retrospect, he was always the guy who was on top of technology. I remember in the ’80s, he had a VCR in 1982, very cutting edge. And then he had a video camera. Nowadays, you have your iPhone, but the video camera, you actually carried that on your shoulder. But he was actually taking home videos with this thing.

Kerri:

That was hot stuff back.

Viet:

It was hot stuff, right? You had to carry a suitcase with this video camera in it.

Kerri:

That’s right.

Viet:

But in our archive, what happened is that we came as refugees to the United States. So it was not as if we could just pick up photo albums and bring them with us. So I think the photos that we brought from Vietnam with just whatever was in my dad’s wallet. So we were lucky that we have a handful of photographs of my father and mother when they’re young and beautiful and glamorous. And then a photograph of my brother and myself that my dad had in his wallet when my brother was probably seven or eight and I was two. And that was the only photographic evidence I had of myself as someone living in Vietnam.

Kerri:

That really alters the way a family tells its story of itself, isn’t it? Because it’s very common for us to sit around and open family albums and kids get to learn about who they are through that experience of hearing about photographs. And you didn’t have most of that.

Viet:

I did not. And then I think we gradually obviously accumulated more because the moment we got to the United States, my father acquired a camera. So we have photographs of ourselves in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where we first stopped. And then eventually other photographs arrived from Vietnam. Those I didn’t include in the book, but that was how I found out that I had an adopted sister when all of a sudden this photograph showed up one day, I’m about 10 or 11, of this beautiful young woman who I did not have any memory of, even though I’d seen her when I was four years of age. And so that photograph of her, black and white, I carry in my mind always because it haunted me and the photograph symbolized that haunting of someone who had been left behind.

Kerri:

I want to put up the picture of Saigon Moi. You have this powerful sense memory from the store that your parents owned in California. Describe what we’re seeing, if you will, and then we’ll talk about what it was like to be inside.

Viet:

This is a black and white photograph, probably from around 1978 to 1980 because we had just moved to San Jose, California from Harrisburg, thank God. And this is downtown San Jose, and it is a one-story strip mall grocery store called the Saigon Moi. And what happened is that my parents had come at the invitation of their best friend, Backwe, who had come to San Jose first and told them in Harrisburg, “You should come to California. There’s great opportunities, good weather.” They came out and they helped Backwe run her Vietnamese grocery store, which was probably the first one in San Jose.

Kerri:

Wow.

Viet:

And then about a year later, they opened the second Vietnamese grocery store, the Saigon Moi, about two blocks away. So I think the definition of friendly competition. And in the photograph, it’s just a very humble store, and there’s a sign above the store that says, “Mini Market, Saigon Moi, Oriental Food.” And that was how I grew up watching my parents work in the store every day of the year except Christmas and Easter, 12 to 14 hours a day. And then they would come home and I would help them process the food stamps, the aid the families with the AFDC coupons. And I was the accountant counting the money and doing the ledgers and everything like that.

But my parents never actually made me work in the store. And in the store there were all these so-called Oriental goods, so cans of Asian food products, 50 pound sacks of jasmine rice stacked to the ceiling, a butcher in the back working on the fish. And that was how my parents saved themselves and saved us by working so hard in that store and also sending a lot of money home to Vietnam because it was a hard time for our relatives back then.

Kerri:

I want you to go back to that eight-year-old boy, what it was like to the smells, the sounds, the texture of being inside that store, which seemed both mysterious and very familiar, because you were there a lot. What was it like?

Viet:

If you can imagine that there were these accordion gates in front of the store, my parents would close them and open them in the morning and the evening, they would creek. And then you walk in and there’d be yellow strips of fly paper. I don’t think people know what that is, but these sticky strips that would be studded with dead flies. And the sounds of the store, it would all be in Vietnamese.

The only people who came to the store were Vietnamese people. I still meet people today who remember going to that store because it was one of the centers of Vietnamese life where you could find your [foreign language 00:11:11] and your rice and [foreign language 00:11:14] and all these things that have very distinct fishy odor that non-Vietnamese people might find odd, but which I found to be home at the same time. And you have to tell you something, fish sauce might stink, but it’s not as bad as cheese, which I found very, very gross. We had no cheese in the store. And yeah, I remember it being a 100% Vietnamese environment, and I grew up with my parents telling me, you are 100% Vietnamese and the store really symbolized that.

Kerri:

You muse in the book, what would happen if I ate a chocolate covered cherry now? Would I remember all I have forgotten or tried to forget? It sounds like you’re almost reluctant to discover the answer to that.

Viet:

Well, it was a very difficult time. I think that downtown San Jose, if you go visit now, it’s kind of a nice place because of Silicon Valley and the tech money that came in. But in the 1970s and 1980s, the only people who wanted to open stores in this area were Vietnamese refugees. And you could walk down Santa Clara Street and there would be tons of Vietnamese stores, beauty salons, video stores, grocery stores, restaurants, cafes. And it was beautiful in one way, but in another way it was really hard because it was also very violent. So my parents were shot in their store on Christmas Eve, we were robbed at home at gunpoint. All of these things were, to me, associated with the life that my parents had to lead in this grocery store. So on the one hand, I could eat anything I wanted, and for some reason we had chocolate covered cherries in the store.

Kerri:

Are they Vietnamese or is that… they just carried-

Viet:

I have no idea why.

Kerri:

They just carried candy chocolate covered cherries.

Viet:

And so I would just eat boxes and boxes of chocolate covered cherries. And I loved that when I was a kid, but I was very afraid, I think I never wanted to eat them again after my parents shut down the store. And so it is a proustian thing to imagine that if I ate that candy, what memories would it bring back? Because I’ve spent a lifetime suppressing those memories because they’ve been so painful.

Kerri:

I want to talk about the violence that you came to associate with your parents’ work, but you also write about how you were very aware that it stole their vitality. It was so… running the store, long hours, so demanding, and you knew that even as a little boy, that they’d come home and they would’ve basically given it all to the business. What do you remember about that?

Viet:

It’s a classic refugee and immigrant story. The parents have to come to this country and then to survive they have to work as I described all the time, and they’re doing it for themselves and their children and everybody else who they might be supporting. But the emotional cost is terrible because then the parents don’t get to have time to spend with their kids. And so I was very lonely growing up. I couldn’t have put any of this into words, this was simply our life, and I never demanded of my parents spend time with me. That would be unheard of because I didn’t want to make their burden even more. And so it was mutual sacrifice that they were working and then I was just trying to take care of myself emotionally, and I think it was damaging. I think that for me, again, I survived by thinking this is the way it is for everybody and it’s normal not to be able to spend time with your parents and it’s normal to spend your life squirreled away into books and trying to fly away by fantasy from this world that we were living in.

Kerri:

Do you think your parents had any clue that, again, in making the American dream come true, they were really depriving mostly you, but your brother too?

Viet:

Well, my parents had no idea they were raising one of the most frightening creatures you could ever have in your house, a writer. Writers are frightening because our material is other people and oftentimes the people closest to us. And so I thought a lot about why it was so hard for me to write a memoir because a memoir is about telling the truth, but that means also potentially betraying secrets, betraying people, betraying the people that you love.

And yeah, no, I think my parents had any idea that when they dropped me off at the San Jose Public Library every weekend, that I was being exposed to all kinds of stories and ideas that they as Catholics would’ve found horrifying, but which played such a fundamental role in addition to the grocery store in their life and shaping me as a writer.

Kerri:

So how in acknowledging that many of these memories had been suppressed for so long and then making the decision that if you were going to begin this, you were going to tell as much of it as you could. So how do you reckon with that idea that there is betrayal in that? And there is also the question as to whether these are true memories or just perspective or some mix of dream and desire, and how do you work with that?

Viet:

Well, I think oftentimes people, I’ve met a lot of people who’ve told me, “I really want to write about a memoir about my family or my community, but I’m scared because I don’t want to betray them. I don’t want to air the dirty laundry.” And in fact, as a writer, whether you’re writing memoir or fiction, that’s your business. Your business is betrayal, I think. It’s not an easy decision. I’m not saying you should take it without a certain ethical and personal concern, which I do. But in the end, you have to betray things. And so for example, I also write a lot about growing up in a Vietnamese refugee community. A lot of Vietnamese refugees do not like me. In fact, I did an event recently and this young Vietnamese American woman came up and said, “You are the second most hated person in my household.”

Kerri:

Really?

Viet:

After Joe Biden.

Kerri:

My gosh.

Viet:

And it’s because I say certain things about our lives as Vietnamese refugees and the politics of the war and the United States and so on, that a good percentage of Vietnamese refugees would disagree with. And yet I think that this act of betrayal, as some of them would see it, is also an act of truth. And so I just have to reconcile that these two things cannot be extricated in so many ways.

And then of course, also, it’s not just me betraying truths about other people, I’m also betraying truths about myself as well. I mean, you don’t want to read a memoir where the writer simply criticizing other people, I have to criticize myself, and one of the most fundamental ways is the unreliability of my memory. And so this book is a memoir, but it’s also about the way that I experienced memory and how my own memories have changed over time to deceive me.

Kerri:

So do you feel like you crossed any rubicons and there was no going back, and now you’ve had to live with that?

Viet:

If that is true for Americans in general, or Vietnamese people in general, if I’ve crossed the rubicon, I really don’t care. If you’ve read The Sympathizer, you can tell I really don’t care. In that novel, I set out to offend everybody.

Kerri:

Explain what you mean. Yeah, explain what you mean.

Viet:

Well, in The Sympathizer, I set out to offend everybody except the Pulitzer Prize committee.

Kerri:

Let it be known.

Viet:

Thank you. That novel is about the war in Vietnam. And in fact, many of my books are concerned with the war in Vietnam, but also the much longer history of French colonization, American occupation, so many political things and things about war. When you talk about those things, there are going to be sides. There are going to be people who just do not agree. And if I feel that my obligation as a writer and as a human being, is to tell the truth about all these sides. And when you do that, everybody will be angry about something. Everybody will be like, well, you pointed out the atrocity we committed. What about their atrocity? And this goes back and forth. And so if you write about war and you write truthfully, you will offend the partisans of every side. That was true for The Sympathizer, and I think it’s true for this book as well.

Kerri:

You seem pretty much undisturbed about that.

Viet:

Yes.

Kerri:

Yeah.

Viet:

Yes.

Kerri:

Why?

Viet:

I think I am a natural polemicist. I really don’t know why, where it comes from, but I think my theory is that I was born a Catholic. My parents are very devout Catholics, and they sent me to Catholic school my entire life from kindergarten through 12th grade with a very Jesuit education. And yet for some reason, I came out an atheist. But the one way that Catholicism has really stuck with me is that I like to suffer and I believe in sacrifice, and I believe in telling the truth even if you have to sacrifice yourself for it. And I believe in justice. And I think that all of those things are integral with my beliefs about myself and what I believe in, but also in what I think a novel or a memoir can do.

Kerri:

I’m wondering how much suffering you’re really doing Mr. Pulitzer Prize winning author on a book tour with a bestselling memoir. I don’t know.

Viet:

Well, you’re only getting the end result, but I like to say that I wrote and drew my first book when I was eight-years-old in the third grade, and the San Jose Public Library gave Lester the Cat a book award, which was my first taste of literary fame. And I’m forever grateful to the San Jose Public Library for setting me on the path to 30 years of misery-

Kerri:

That’s so true.

Viet:

In trying to become a writer. So yes, getting the Pulitzer Prize is awesome, no doubt about it. But there was 30 years of misery before I got to that point.

Kerri:

Okay. You say so. At the beginning of our conversation, you alluded to the fact that your father, the photographs that you had when you arrived in America were whatever he had in his wallet. And I wanted to talk a little bit about what you’ve described in the memoir about how your parents left Vietnam. In 1975, your father is in Saigon on business, and your parents’ village is captured by the North Vietnamese. What happens?

Viet:

This was March 1975, and we were the first town captured in the final northern invasion. And so all lines of communication were cut off, and my mother is left alone with her three children. My adopted sister who was 16, my brother who was 10, and myself who was four. And so she had to make a life and death decision and the decision that she made was that she was going to flee on foot with my brother and me, but not with my adopted sister, leaving her behind at 16 to guard the family property with the idea that we would come back, because I think she genuinely believed that, the war just gone back and forth for a very long time. And of course, we did not come back. And can you imagine being 16 years old surrounded by an enemy army and being tasked with guarding the family property, which she obviously could not do.

And then, so we fled on foot, and we eventually made it to the nearest seaport, Na Jang, caught a boat, made it to Saigon, found my father, and a month later did it all over again because the communist army arrived in Saigon. And we had a very harrowing escape story where my parents tried to get out through the airport, couldn’t do it, get out through the US embassy, couldn’t do it, made it to the docks. And then at the docks, which were overwhelmed with people, they were separated. My father, again, was separated, and my mother was left alone with us. And separately, on their own, they both decided to get on different barges without knowing what was going to happen to the other. And then we were lucky again because both barges were picked up by a US ship, and we found ourselves on this ship. And that was the story of our initial escape from Vietnam.

Kerri:

I mean, your mother had to walk with you two boys for how long? Days?

Viet:

187 kilometers through a landscape that was completely torn up because the South Vietnamese army had collapsed, so there were all these soldiers fleeing in addition to all the refugees fleeing, and obviously the North Vietnamese army was coming as well. So it was chaotic, it was horrifying.

Kerri:

Did your mother ever describe how she made this decision to leave the adopted daughter behind, and to take you two. Of course, you two were young enough that you had to be with your parents, but did she ever describe how she made this decision?

Viet:

No, she never brought it up, and I never asked her because sometimes my mother and my father would tell me stories, but mostly my mother about their pasts in Vietnam. And sometimes those stories were really horrifying. My mother, for example, one day I was probably 10, I was plucking gray hairs from her head for a nickel a strand thinking, how many of these strands of hair would I have to pluck in order to get the next Captain America? And then out of nowhere, my mother says, “I remember that there was a famine in our country in the north that killed a lot of people.” I don’t know if she said the exact number, but it was about a million. And-

Viet:

I don’t know if she said the exact number, but it was about a million, and she remembered dead people on the doorsteps in the village, and I said nothing because I did not hug her. I did not say anything. I just kept on plucking the hairs. Like everything else that I encountered in my parents’ lives that recalled the violence that they encountered there in the United States, I think I withdrew and became emotionally numb, and therefore I didn’t want to ask them questions because I think I didn’t want to know. And also I was afraid because I knew that they’d been through so much and I didn’t want to risk reawakening experiences that perhaps they didn’t want to talk about, that they hadn’t wanted to talk about it. Why should I make them talk about it?

I think that for so many of us who are refugees, part of what we experienced, especially my generation, the children and the grandchildren, were things that were said to us, but then the things that were not said, the silences, the absences, those carried enormous emotional meaning as well.

Kerri:

I mean, was it the unspoken, I don’t know, code or creed in your family that you did not ask, not even about the difficult things, but you really did not ask about what life was like, who had been left behind? Somehow that was communicated to you. You didn’t just decide that this could be painful, so I won’t ask. No?

Viet:

No. I remember my mother telling me also out of nowhere at the dinner table. Yeah, they came as refugees the first time from the north to the south when the country was divided in 1954. My mother was 17, my father was 21, they’d just been married and they had no money. And my mother said, “Yeah, when we first got to the South, I had to pick up Buffalo dung to try to make some money.” And my father said, “Why are you telling him that story? Don’t say that story.” And so there was times when it was very clear there were things that I was not supposed to know, or that if I did hear them, I wasn’t supposed to betray them to other people. The fact that my mother only had a grade school education, for example, that was an embarrassment, that was shameful. I was growing up reading The Sound and the Fury, and then I would come home and my mother would be reading the church newsletter with a magnifying glass and reading out loud very slowly as she tried to pronounce the words and everything.

And so I think that I absorbed this idea that if there were things that I was curious about, people that I was curious about, I would have to keep it to myself, but the information would leak out. Again, these photographs would arrive from Vietnam with the relatives. We had so many relatives that had not left the country. If I was to ask about all these people, there would be literally dozens of them, of stories, that I would have to understand. And I remember very vividly on my parents’ bookshelf, they’d had very few things on their bookshelf. They had no books on their bookshelf, not even a Bible.

But one thing they had was a photograph of my father and his three brothers. So he had left in 1954 with my mother’s family, but nobody else from his side left, which means he didn’t see anybody from his family for 40 years until he was able to go back to that village. And here was this photograph of my father and his brothers, and they were grown men. And it took me years to recognize, and in fact, that was impossible because my father had left when he was 21, and all of his brothers were younger than him. They were boys.

But this picture was four grown men. And I looked closer and I realized my father before Photoshop had taken two photographs, cut them apart and spliced them together, himself as an adult man and his 40s and his 3 brothers who had taken a photograph from Northern Vietnam and sent it to him. And when I saw that line between my father and his brothers, that just symbolized for me everything that he had been through and everything that I could not ask him about. What was it like to leave your entire family behind? How could I ask that question?

Kerri:

And where would you even begin, I guess. Because once you opened that door, it was frightening about what would come out.

Viet:

Yeah, I was frightened of the past and he didn’t want to talk about it.

Kerri:

You write, you do not remember if you remembered having a sister. You last saw her when you were four. And how long did your memories of her persist after that?

Viet:

I don’t think I had any memories of my sister. And that was why when that photograph showed up when I was 10 or 11, it was a shock, I think. And that was my first time I think hearing her name, [foreign language 00:29:58]. And of course, I didn’t ask any questions at the time. I was like, what was I supposed to ask my mother and father? Why did you leave her behind? How could I ask that? And so then I was haunted again by that absence, but also I think also haunted by something I couldn’t ask out loud, which is why me and not her? Why was I brought along and not her?

And I think for so many refugees and immigrants and people who have survived terrible things, there’s a sense of survivor’s guilt. There’s also a sense of what if, the alternate universes that we could have lived if history had just taken a different turn or if our parents had made a different decision. And I’ll never forget one time, a so-called friend said to me, “Oh yeah, there’s a rumor in the community that you’re adopted.” So I went home and I told my dad, and he got so angry. He said, “No, you’re my son. I’ll take a DNA test,” which we never had to do that because I believed him. But afterwards, my brother pulled me aside and he said, “Do you know why you’re not adopted? It’s because mom brought us and not our adopted sister.”

Kerri:

When your parents got into the United States, they get to a refugee camp, and they are told that it will be better if the family is separated. And before we hear the excerpt, tell us a little bit about the photograph that we’re going to see. And this is you in a tree. How old were you there?

Viet:

I imagine I was probably five years old or so. And I am in a natural setting in a park sitting on a tree trunk. It’s just me in a t-shirt, in a short sleeve shirt and shorts wearing flip-flops or sandals. And the photographer is very, probably my father. This is Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. We had left the camp around 1975, late 1975. And I remember this time with great fondness actually, because at this time my parents didn’t have a grocery store. They were not entrepreneurs. And so they worked nine to five, they worked as custodians in the local nursing home. And then my father went to work for Olivetti, a type writer manufacturer. And so they didn’t have very much money, but they had time. So we could do things like picnics and walks in the park. And I loved that time.

Kerri:

That looks so quintessentially American, doesn’t it?

Viet:

Yeah, from the mid 1970s with the floppy hair and everything else.

Kerri:

And little boy climbing a tree here.

Viet:

I was kind of cute back then, I think.

Kerri:

You were. Tell me about this, what happens when your parents decide that they’re going to go along with this advice that the family has to be separated?

Viet:

I had to speculate about that because I don’t know. And so what happened was that in order to leave the refugee camp, and there were 130,000 Vietnamese refugees who fled in 1975 and ended up in one of four refugee camps in the United States. 22,000 Vietnamese and some Cambodian refugees ended up in Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania. And in order to leave the camp, you had to have an American sponsor you. So there was no American willing to sponsor all of us. And so one sponsor took my parents, one sponsor took my 10-year-old brother, one sponsor took 4-year-old me. Apparently this was unusual even by Vietnamese refugee standards. Even Vietnamese refugees are shocked when they hear this story.

Kerri:

Really?

Viet:

Yeah. It didn’t happen to anybody else that we’ve ever heard of. And so I never knew why that was the case, and I had to speculate it about it because I never asked my parents either, so I had to speculate about it in the memoir.

Kerri:

I just can’t imagine your mother, your parents going through the escape, the separation, then the separation again, then another separation once they get to the United States. And yet you are ultimately reunited. How?

Viet:

Yes. How? I think it’s in the excerpt.

Kerri:

Okay, good idea. Right.

Viet:

Getting ahead of myself.

Kerri:

Exactly. Let’s hear the excerpt.

Viet:

“Someone is telling [foreign language 00:34:15] that their best option is to break up the family. Someone is telling them something to send their sons away with strangers. Something, something, something. Ma’s English is limited. Ba’s English is good enough to do business. So perhaps he completely understands what is being said or perhaps he understands most of what is being said. It is what he cannot understand, the missing 10 or 20% that confuses. Something, something something. Did Ba just hear right? Did this person say what he is thinking they said? [foreign language 00:34:54] nod, showing they’re listening, if not fully understanding. Something, something, something. Perhaps a fellow refugee translates, or perhaps the translator is one of those Vietnamese international students already in the United States who has volunteered to help. It takes minutes, perhaps hours for the reality to be absorbed into the mind and the flesh. Perhaps [foreign language 00:35:20] argue, perhaps one is for it, one against it. Perhaps both are against it. You cannot imagine both agreeing to the separation, but in the end they do.

Perhaps the sympathetic person helping them tells them that this is their best first opportunity to leave the camp. If they don’t take it, they might be stuck here for much longer. [foreign language 00:35:46] weigh the costs and benefits of staying in the camp with their sons, of leaving the camp without them. They rationalize the emotional damage that will be done to their sons, to themselves. Ma remembers how she left her mother behind and all her many sisters. Ma recalls your adopted sister all alone. What is her adopted daughter doing now? Ba thinks about how he left his father, brothers and sisters behind in 1954, the first time he became a refugee. He has not seen them since, and he turned out all right, didn’t he?

This is a war story. You imagine, but you do not feel what [foreign language 00:36:37] suffered because while you can imagine being separated from your son, you cannot feel what that feels like. The gap between imagining an emotion and feeling it is the distance between empathy and experience. The divide both writer and reader face as empathy brings them closer to others, but cannot make them into those others. Empathy cannot turn a son into his father and mother, even if the son is also a father. You do not have to make the decision that [foreign language 00:37:18] must. And in the end you turn out, all right, don’t you? Even branded between the shoulder blades with this mark of the other, you are the lucky one, separated for only a few months from parents who you feel are a part of you. Your brother, seven years older, doesn’t come home for two years, and that, your brother says is how we know mom and dad love you more.”

D’Lourdes:

(Singing). Thank you.

Kerri:

D’Lourdes. I’m struck by the lyrics and what a great fit they are to our conversation. How’d you choose the song?

D’Lourdes:

Well, I think it’s the most current and vulnerable one I have, and welcome to Cold Season everybody. But I wrote it a couple of months back, just getting older and kind of just mourning who you thought you’d be, how your life changed in the way that you thought it wouldn’t, and just accepting the melancholy of being an adult. And how …

Kerri:

Are you 23?

D’Lourdes:

I’m 25. I’m 25. I know, I know.

Kerri:

I feel your pain.

D’Lourdes:

I know. And it’s that I always have felt 25.

Kerri:

You have?

D’Lourdes:

At 13, I’m like, I’m in my 20s. I don’t know what you’re talking about, but then when you actually turn the age, you’re like, oh, I’m actually seven. I don’t know why I was rushing to get there, but …

Kerri:

Lovely to have you tonight. Thank you.

D’Lourdes:

Thank you so much for having me.

Kerri:

You’re listening to Talking Volumes at the Fitzgerald Theater with author Viet Thanh Nguyen, his new memoir is titled A Man of Two Faces, A Memoir, A History, A Memorial, and for the audience at home, we’re showing photographs from Viet’s family collection on a large screen behind us as we talk, and we’re doing our best to describe those pictures for listeners who couldn’t be here. You have been at the center of a literary brouhaha this week. You were scheduled to speak at the 92NY in New York. Was it last Friday?

Viet:

Yes. Just a few days ago.

Kerri:

When the event was abruptly canceled because of a letter you signed about Israel’s war with Hamas, 750 other artisan authors, I want to say, signed the letter. Would you talk about how the letter expressed something that you felt needed to be said?

Viet:

Yes. I mean, I signed it because I think it is important, as I mentioned earlier, for writers to commit to the truth as they see it. And I speak from a perspective of someone who is a refugee, was a refugee, feels like he still is a refugee in some emotional way, and came from a history of the war in Vietnam that was enormously divisive. I think many of the audience just judging from how old you appear, may actually have lived through that time period. But I teach 19 and 20 year olds and they have no idea. For them, the war in Vietnam, the American war in Vietnam is ancient history. They hadn’t even seen movies about the Vietnam War, for example.

Kerri:

Really?

Viet:

And so that feels like ancient history. But for me, from my understanding of it, from the American perspective, it was deeply divisive for Americans. I characterized it in one of my books as a civil war in the American soul. And in The Sympathizer, I characterized the war as a tragedy, not because it was right versus wrong, but right versus right. Both sides so passionately committed to what they believed in. And when the world is divided in that way, into us versus them, it’s an absolute binary where our side is good, their side is evil, they commit atrocities, we conduct humanitarian warfare. When they kill civilians, it’s because they’re evil. When we kill civilians, it’s an accident. We would never intend to do that. So I see so many echoes and parallels with what’s happening in Gaza and Israel and Palestine and in this current conflict with what had happened earlier.

That doesn’t alleviate the pain and the horror that everyone is experiencing from the first massacre committed by Hamas to the airstrikes being carried out by the Israeli Air Force. And then the much longer history of occupation as I perceived it, that took place before. And I feel that the role of art is not to take sides, is not to judge whether one side is good or one side is evil, to say that we are human and they are inhuman. And when we’re living through a war, that’s what we’re tempted to say. We’re human. They’re inhuman. My perception, my argument, my belief is that in fact, we are human and inhuman at the same time that everybody, every side is capable of committing and doing terrible things.

And when we deny that inhumanity within us and we project that inhumanity onto our enemies and our others, we actually are not doing anything to stop wars. We’re only perpetuating the cycle of that war. And so that’s what I hope that that letter captured. And then I also wrote additional messages on Instagram to frame what I wanted to sign that letter. And I think the reason why I wanted to sign that letter is because I believe that art is actually one of the things that could help us even to imagine an end to war by making us recognize, again, not this duality between good and evil and human and inhuman, but to recognize the inhumanity within our own humanity.

Kerri:

What I’m puzzled about the reaction, the cancellation of your event, although I know it was moved and you ended up doing it anyway in New York. I think we want perspective, we will want a lot of different dimension on something that is unfolding day to day. It is chaotic and confusing, and I want to know what a lot of different people think, including artists and authors. And I’m puzzled as to the reaction on this letter, which is in a sense, I don’t know, your perspective would be valuable, keep to your writing, you don’t have a role to speak on this. I mean, that’s what it sounded like to me. How did it sound to you?

Viet:

It sounded to me, I mean, much of the reaction to the letter by people who didn’t like it is couched in very specific, I think US dynamics around Israel, Jewish Americans, and the kind of political climate that we have had for a while where for some people, any criticism of Israel is construed as antisemitism, which I don’t believe to be the case. It’s not to say that antisemitism doesn’t exist, it does, and that some criticisms of Israel can be antisemitic. That’s absolutely possible. But again, when we think about when we divide the world that immediately between us versus them, we homogenize both sides. And those sides are actually not homogenous. It’s not as if Hamas represents all Palestinians. There are many Palestinians who would tell you, we don’t agree with Hamas.

And when we talk about Israelis and Jewish Americans, I don’t think we can homogenize either because there is an Israeli left that says many of the same things that are actually in that letter. And there are Jewish American progressive voices that will say many of the same things that are in that letter. And then of course there are Israelis and Jewish Americans who completely reject that letter. That’s exactly what a discussion is supposed to bring out, and that’s what art is supposed to bring out. I think that was really, really unfortunate. I would’ve been happy to show up in the 92nd Street Y, and if people were in the audience and said, “We disagree with you and all these other writers signing this letter.” I’d be like, “Okay, then let’s talk about why.” But again, I think that the political environment around Israel and the United States is actually so censorious that it tempts me to speak up more for Palestinians and for Israelis because in a sense, the entire United States is geared to side with Israel at this moment and has been for quite a while.

Kerri:

I guess I thought we learned some of this lesson after 9/11 when there were things that couldn’t be named and couldn’t be criticized. And there’s been a lot of retrospective on that and rethinking and reflection on that. But here we are again in some ways.

Viet:

I remember very clearly that President Bush immediately afterwards said, “It’s us versus them,” and you had to choose. And there was nothing original about that, surprisingly. And there’s nothing original about what’s happening now. In fact, Israel going down the path that it’s doing is going to kill enormous numbers of Palestinians, which it already has, about 5,000 in addition to the 1,400 or so Israelis who have also died during this conflict so far. But you can easily see that Israel continuing down this policy of us versus them is only going to lead to even more fatalities, certainly for Israelis, but an even greater number of Palestinians.

And so I think it is the role of artists to say, wait, it is not us versus them. Let us remember the humanity of the people who are going to die and who have been dying. Let us remember the humanity of the Israelis and the soldiers and so on. Again, I go back to my experience studying the Vietnam War so closely. If we talk about soldiers, their humanity is destroyed too when they’re asked to go out and kill people. And then the ripple effects of that will ripple …

Viet:

And then the ripple effects of that will ripple through their families and their children. It’s not just the soldiers who are damaged. It’s their loved ones as well. And it’s not just the soldiers who are traumatized and whose humanity is eroded. It’s the soul of the nation that’s eroded as well. I think the war in Vietnam really did tremendous damage to American culture, American humanity, and in many ways for a while, the lessons that the United States learned from the war in Vietnam for two or three decades was, let’s not do this again. Or at least there was enough opposition to say, let’s not do this again. It was a bad war. And now again, it’s history. And I think the United States, at least at the level of the government, military, political leadership, bipartisan leadership, has gotten all the wrong lessons from the war in Vietnam so that now the lessons of the war in Vietnam for the American military and political establishment is how can we wage better wars based on what we’ve learned from the war in Vietnam?

Kerri:

I want to talk about the language that you use of refugees. You very deliberately, you are specific in thinking of yourself as a refugee and not an immigrant. Let’s describe the photograph that’s behind us.

Viet:

This is the photograph that my father carried in his wallet of my brother and me. And again, I think my brother was probably eight or nine years old and I looked like I was about two. And it’s a black and white photograph. It’s really creased and crumpled because it was in my father’s wallet and it’s just my brother with his head on my head leaning his head against mine and with his hand on my shoulder. And I just want to point out that my head at two years of age is as big as my brother’s head, and he’s seven years old. I have an enormous head. Okay? And that has stayed a constant in my life. But I have no memory of this moment. I have no memory of this photograph. And when I was growing up, I would go visit other Vietnamese refugee homes, and in every household there would be these black and white photographs that people had carried with them from Vietnam and they would be photographs of themselves, but oftentimes they’d also be photographs of the people who had been left behind.

And so to me, these black and white photographs symbolized histories, symbolized absence, symbolized haunting. And I feel when I look at this photograph, even though my brother and I are both alive, I’m haunted by this past, I’m haunted by who we were as children and that we were probably happy children from what I’ve been told and that I have no memory of this. And so when I became a father and my son turned two and three and four, it was my occasion to look at him and finally think about myself at that age, which for decades and decades I refused to do because I think as a refugee, the lesson I learned is you never look back. Because if you look back, you can be trapped in your past and in all the horrible things that had happened and the people that had been left behind. So you must look forward, forget the past, don’t feel, keep moving forward. That’s how we would survive in this country.

Kerri:

So those boys are refugees. Even as adults, they’re not immigrants?

Viet:

Well, that’s a complicated question and a complicated answer. We are a country of immigrants. That is a part of the mythology of the United States. Even in a xenophobic time, even xenophobes would still say, “We’re great because people want to come here as immigrants. We may not want them, but they want to come here. And that’s proof of how great of a country we are.” Refugees are a completely different story because refugees are the unwanted, they are subhuman, they are a crisis. And yes, we take in refugees, but they’re not the same as immigrants. Immigrants come here by choice. They come through legal programs and so on. Refugees just flood our borders and so on and so forth.

And so I’ve met so many Vietnamese refugees and other refugees from other countries who don’t call themselves refugees because they’ve learned from a very young age or after very little exposure in this country, do not call yourself a refugee. People will not understand. If you introduce yourself as a refugee at a cocktail party, no one will know what to say to you. You introduce yourself as an immigrant, and Americans will be like, “Well, hopefully, welcome to our country. And tell us about how you achieve the American dream?” That’s a story that people want to hear. So refugees learn to call themselves immigrants in this country.

At the same time, I’ve met so many Vietnamese refugees who also, at least to themselves in their own language in Vietnamese, or at least with other refugees, will call themselves refugees. Even if obviously I’m no longer a refugee by fact or by law, I feel like I will never cease being a refugee because I have never ceased feeling the emotions that we’ve been through, the trauma that we’ve experienced. And so many Vietnamese refugees have read my books and they’ve cried and they’ve come up to me and said, “God, I have tried not to think about these emotions for 30 or 40 years. I’ve tried to assimilate into the society. I tried to move forward.” But when they read these stories, my stories and the stories of other refugees, all those emotions that they have tamped down for so long, all those feelings, they come back out. And that’s how you’ve never stopped being a refugee.

Kerri:

What do you think your parents would think of that, or think of that? Because it sounds like it was all about giving you that immigrant story and not raising boys who would forever think of themselves as refugees with all the pain and loneliness that goes with that.

Viet:

Well, again, a very complicated story because again, when I was growing up, my parents would always say, “You’re 100% Vietnamese.” We only spoke Vietnamese. We only ate Vietnamese food. We only went to Vietnamese language mass. And so I don’t think they thought of themselves as immigrants. They never wanted to be Americans. When they said Americans, they meant other people, not us really. We were always Vietnamese. We were never Vietnamese Americans. That was never even a word or term that I heard of until I went to college and we invented that term, my generation, for ourselves.

And then 20 years after they arrived in the United States, the United States reestablished relations with Vietnam. And actually my parents took the earliest opportunity, around 1994, ’95 to go back to Vietnam. And then they came back and over Thanksgiving dinner, my father said, “We’re Americans now.” Again, a classic refugee or immigrant story. When refugees or immigrants come to this country, or probably any other country, they hang on to that moment that they left, 1975 in our case. Vietnam is frozen in their memories and their feelings. Our language was frozen. If you go back to Vietnam and you speak 1975 Vietnamese, people will immediately know you are not one of them because the vocabulary changed. The word for airport is different. So if you arrive at the airport and you say, [foreign language 00:57:10], everybody will know you are a 1975 Vietnamese person.

Kerri:

Really? Wow.

Viet:

Because now they call it [foreign language 00:57:17] instead. And so we always thought of ourselves, I don’t know if the term my parents used was refugee or immigrant. We were certainly not Americans. But then of course, when you go back to Vietnam and you see that the country has changed in 20 years, and now 40 and 50 years later, it’s changed even more. You recognize how much of an American you actually became.

Kerri:

And were they comfortable? So then 20 years later, they wanted to embrace that. And what did that mean?

Viet:

I think it was always an ambivalent embrace. I think what they encountered in 1994 and ’95, you have to understand, Vietnam had suffered through tremendous deprivations after the war, partly because of the government’s collectivist economic policy, but also because the United States had waged war by other means, by imposing a boycott on Vietnam for 20 years and making life very difficult for the government and the people. And the Vietnamese government had only in 1987 declared that they were going to turn to the market economy. And so my parents came in ’94 and ’95, it was still a very poor country. And all of my relatives are poor. And so my parents went back to the village and it was as they had left it, I think in 1954.

Kerri:

Wow.

Viet:

And so that’s how I think they felt themselves to be Americans because they realized they can’t go back. They live in suburban San Jose in tract home. How are they going to go back and live in a place without running water, which is where my uncles were living, I think, at the time they were still living in the same compound that my paternal grandfather had built. And so then I think that they still called themselves Vietnamese by the time my mother died, but they were buried… my mother has been buried in an American cemetery with a Vietnamese section. They’re buried in the Vietnamese section of the American cemetery, but nevertheless buried here. I asked my father a couple of years ago, “Do you want to go back to Vietnam one more time?” He said, no. I think he’s done. He recognizes that his journey will end here in the United States.

Kerri:

And he is at peace with that?

Viet:

I think so, yes.

Kerri:

Is there any way to assess whether some of your feeling of being a refugee and not an immigrant is also some kind of guilt about being one step removed from this experience that your parents, not having had to go through the privations and the things that they endured and suffered? Is there anything to that?

Viet:

I was a refugee too. I mean, I was brought over when I was four years old. I went through the fall of Saigon, but I don’t remember any of that experience. And so can I be an eyewitness to history? In the memoir, I say I’m an eyewitness to my parents and what they went through. And I think that in the book I constantly stress civilian stories can be war stories too, because that’s what I witnessed. My parents were not soldiers. They never went through war as combat soldiers, but the war touched every aspect of their lives.

And I’m pretty sure my parents saw more horrible things than some soldiers did. Because I know a lot of American soldiers went to Vietnam and they never saw combat. They were on a Navy ship or they were guarding a base. They never saw combat. But you know what? Every single refugee who has come to this country, if you ask them, has a horrifying story to tell you. By definition, if you are a refugee, you have survived a horrible experience or you haven’t. There are all these refugees who never made it, all these refugees who never made it. Either they were captured, they were sent back, they died at sea, they died in minefields. They never made it. And then the ones who did make it had to go through these harrowing experiences and they get to this country. And then most of them did not talk about these experiences with their American raised children because how are these American raised children going to understand?

And so in fact, even if I don’t remember, the experiences my parents went through in that grocery store and the Vietnamese refugee community that I grew up in that was so deeply traumatized, those in fact are refugee experiences that I was immersed in. So I feel I can claim that eyewitness experience to that refugee experience and that is also a refugee experience because there are so many children who are refugees and they are so damaged by what they’ve been through. And most of them, if they survive that experience, will try to look forward and not look back, but they will have internalized that damage.

Kerri:

I thought we could put the photographs of you and your mother. That’s an incredible picture. Let’s describe it. She’s in a tunnel of trees and holding your hand. This is in Vietnam?

Viet:

This is a black and white photograph that my father undoubtedly took, and it is in a rubber plantation outside of our hometown of Ban Ma Thuot now called Buon Ma Thuot in Central Highlands, Vietnam. And my mother is probably in her late thirties in this picture. And she’s statuesque, her hair is in a bouffant. She has black sunglasses on, she has a purse on her shoulder. She’s wearing an [foreign language 01:02:45], the Vietnamese dress for women. And she is twice my height at the very least. I’m probably three years old. I’m wearing a white short sleeve shirt and pants and I’m holding her hand. I have no memory of this photograph. I have no memory of this experience. And yet to me it seems like I’m deeply in love with my mother. She is my world as I’m holding her hand at this point. And I know because my children, my son is now 10, but he did the same thing when he was three. My daughter is three right now, I’m hopefully her whole world to her as well, along with her mother.

And so I can project those feelings back onto this moment and about how this was such a wonderful moment for me. And this is the opening photograph of the book because it symbolizes memory for me. It symbolizes that I went through this experience, I had this love, and yet I can’t recall it.

Kerri:

You write, “Childhood photos are imbued with poignancy, parents knowing that what they remember, their child may not. As for ma, what did she remember?” A question you ask yourself almost every time you think of her now. Why?

Viet:

I grew up very self-centered. I thought about myself all the time. And if I ever thought-

Kerri:

Don’t we all?

Viet:

Yeah, well me maybe more than most because I’m a writer. But when I would think about the trauma of our experiences and so on, I would think about what did it do to me? Not so much what did it do to my parents all the time. But then when I became a father, my son, when he turned four, it was around 2017 and this was the time of the Trump administration’s border policy of the southern border, destroying families, separating children from their parents, putting them in detention centers or cages in some cases, losing children in this system. And that was my first occasion, I think, to really think deeply about what it must have been like for my parents when their children were taken away from them when I was four.

And I remember my first memories, my first real memories are of that moment when I was taken away from my parents in that refugee camp and I was howling and screaming because I didn’t understand that this was being done supposedly for our own good. When you’re four years old, you only understand the abandonment and the fear and the terror. And unfortunately that’s sometimes what memories are made of, the scarring, the burning of fear and terror into us. And so when my son turned four and I thought about what those families were going through at the southern border, I thought they will never forget what has happened to them. Never.

Kerri:

That’s right.

Viet:

And if I was a parent, I would be so deeply traumatized by having my child or children taken away from me. I couldn’t even imagine what it would be like if my son was taken away from me for any reason. And so yeah, I mean, I think sometimes, for us to understand our childhoods, some of us do have to become parents so we could see ourselves through our children. And I’m not a sentimental person. I’m not telling everybody in your audience to become parents. No, no, no. A good percentage of your audience should not become parents. Unfortunately, we don’t know who. But for me at least, becoming a father was enormously beneficial in helping me develop that sense of compassion and empathy for myself, but also for my children and for just all children as a whole.

Kerri:

One last question before we hear the next excerpt. What if you had the power to create an image from your childhood that you don’t have? What would it be?

Viet:

Wow, that’s an incredibly hard question. What image would I have? I think I would like to have an image of all five of us, my parents, my brother and me, my adopted sister. I don’t have any of those images in my head. I don’t have any of those images as photographs. There must have been a time before April or March, 1975 when we were all together at the dining table, for example, in the house and we were all smiling. I would love to see that picture.

Kerri:

Would you read another excerpt?

Viet:

Sure. I am Ma’s descendant. What does it mean to write my mother’s obituary, my mother’s story, to claim dissent from her, especially since Ma would not want me to write about her this way? Not that she ever forbade me, she trusted me, whose books she never read but was proud of anyway. And since she never consented to this story written in a language she had difficulty reading, am I betraying her? If I do betray her, can I be loyal at the same time? Her life is epic, and yet quotidian, deserving to be told and known according to me, if not her.

Her story matters because she is Ma, but it also carries weight because it resembles those of many other Vietnamese refugees. Heroic as she is to me, perhaps Ma is not exceptional to anyone but those who love her. But saying my mother may be more typical than exceptional is no loss. When I hear stories of other refugees and what they survived, or not, I am immediately captured by their gravity. Not the same as Ma’s, but similar. Not exceptional, but common. Not stereotype, but history. Each one deserving a story. Each one with potential to be portrayed and perhaps betrayed.

I write about math because I believe stories matter. But if stories can dismember as much as save, what does my version inflict on her? If I remembered everything about Ma and wrote it down, is it betrayal?

Kerri:

DeLordes. Thank you.

DeLordes:

Thank you.

Kerri:

You’re listening to Talking Volumes at the Fitzgerald Theater. I’m Kerri Miller. We’re here with author and memoirist, Viet Thanh Nguyen. His new memoir is titled, A Man of Two Faces: A memoir, A History, A Memorial. Let’s raise the lights and we’ll go out into the audience for some questions. You have a question, raise your hand. We have people with microphones. Do we have somebody up on the upper balcony up there? Yes. Okay. You people too. If you have questions, microphone’s behind you. Okay. Right there on the left-hand side. The student from Luther College. Hooray.

Speaker 1:

Anyways, my name is [foreign language 01:13:12] and I usually go by Michelle. Anyway, and I’m obvious from Vietnam, you can tell. But anyway, I’m from Luther College and I’m joined with the group here for the light interview, and I really enjoy it and appreciate it.

Kerri:

We’re glad you came.

Speaker 1:

Yeah. Anyway, I was really interested in light to get to know you as more like your writing journey. And I know that your debut novel, The Sympathizer was such a huge success. And I’m sure this bring you a lot of change, your writing career and your journeys. And I really want to ask you about your writing journey post this milestone. And have you ever experienced what is so-called sophomore syndrome and how the sympathizer affect or help you reshape or navigate yourself or your writing style in your writing journey?

Kerri:

Wow.

Viet:

Thank you for that question. Cool.

Kerri:

Those are some heavy questions there.

Viet:

A question about writing writers love questions about writing. Before The Sympathizer, I had written a short story collection called The Refugees, which took me about 17 years or so to write. And every single moment was miserable in writing that short story collection. That’s how I learned how to write. Now, if you read it, I think it’s a wonderful experience to read because no one wants to hear about the writer suffering, but I did suffer writing that book. But I couldn’t sell it, couldn’t sell it. And so when it came time to write a novel, The Sympathizer, I decided that because I had written the refugees worried about what other people thought, agents, editors, reviewers, but also my fellow Vietnamese people, I decided with The Sympathizer I was going to write that book for myself. That was enormously liberating and it made The Sympathizer a very different book than the The-

Viet:

… liberating, and it made The Sympathizer a very different book than The Refugees. And then I was very lucky, it was successful and so on and won the Pulitzer Prize. And at that moment, I thought, you brought up the sophomore slump, the second book issue, and I thought, what am I going to do with the second novel? Am I going to try to win another Pulitzer Prize? But then if I thought about it that way, I would be worried about what other people thought. And I thought, I have won one Pulitzer Prize. That’s enough. Colson Whitehead didn’t think so. That guy got two.

But I thought winning the Pulitzer Prize actually should not make me anxious about winning more prizes. It should set me completely free to write whatever I wanted to, which is how I wrote The Sympathizer. And so in fact, when I wrote The Committed, the second novel, it wasn’t the next book I wrote after The Sympathizer. I’ve written other things. But in writing The Committed, I also did not care what anyone thought. And so with The Sympathizer, I tried to offend the Americans and the South Vietnamese and the victorious North Vietnamese. And then when I finished that book, I thought, who else is there left to offend? The answer obviously was the French. And so yes, The Committed is set in Paris. And I have to say the French actually have taken it very well. They’ve actually taken it better than a lot of Americans took The Sympathizer.

Kerri:

That’s funny. Right over there on the main floor.

Ken Williams:

Hi, my name is Ken Williams. I’m also a refugee from Vietnam. We escaped in ’75. Thank you for sharing your story and bringing up a lot of traumatic memories as well. I would like to know about your journey with your TV show on HBO, how that came about, how that’s been working with very famous actors and yeah, where the status is with that?

Viet:

Well, now I can say things like, I do get to have lunch with Robert Downey Jr. Which has actually happened.

Ken Williams:

What’s that like?

Viet:

Oh, it was really cool. I mean, the first time we had lunch was when he and Sandra Oh, who was also cast in the TV series as Ms. Mori, they took the actors and the directors and myself and the producers out to lunch at one of the… I think the Beverly Hills Country Club or the Bel Air Country Club, whatever, I would never normally be invited into one of these clubs if it wasn’t for Robert Downey Jr. And then the second time I went to the set and they were shooting in the mountains above Los Angeles, and he said, “Oh yeah, come have lunch with me.” Or not him. His assistant said, “Come have lunch with Robert.” And so Robert had his own trailer, of course, and his own chef, of course. And so it was him and me and his assistant. And it was like, wow, that’s pretty cool because the only reason my son cares about TV series is because Iron Man is in it. And Robert did sign a poster of Iron Man for my son.

And he also signed another thing, which is something I can’t reveal yet. I can’t reveal the item, but if you read The Sympathizer, there’s another book within the sympathizer called Asian Communism and the Oriental Mode of Destruction. Well, the prop department produced that book and it’s authored by Richard Head and Director Park Chan-wook’s genius idea was he was going to cast one white actor to play all the white guys in the book. And so that’s Robert’s role, and he plays Richard Head among other characters. So he signed the book as Dr. Richard Head.

So yeah, you can imagine it’s a very weird experience because when you’re a writer, you write in solitude most of the time. And then this TV series, I think it costs $100 million, or so I’ve been told, involves hundreds of very talented people. It’s a collaborative enterprise. And so it’s not really my TV series, it’s our TV series or it’s their TV series. And it was a very long process to get it made because when the novel won the Pulitzer Prize in 2016, there was interest, not enough interest, but there was some interest. And I remember the first producer I worked with, an Asian American woman, super talented, did a lot of great stuff. We were on the same page. She went out to try to get it made and we wanted to do a TV series. And at the time, we were thinking what to model it on? And we thought Narcos, because Narcos was a hit and it cost about $50 million and it was a foreign language kind of thing.

Ken Williams:

Oh yeah. So good.

Viet:

And so she went out, she tried to get it made, she came back many months later and said, “You know what? For this budget, this kind of TV show, what I’m hearing from the studios and producers is, well, we would need to get someone like Keanu Reeves to be cast in this.” And I thought, that’s kind of racist because Keanu Reeves is not even Vietnamese. He’s mixed race, but that’s it. And then at the time, Narcos didn’t have anybody famous in it. It had Pedro Pascal, who’s now famous, but back then it had nobody famous. So you can make Narcos for $50 million, but if you do an Asian language production, we have to have Keanu Reeves in it?

And so it took so many years of just meeting with so many people. And finally we landed Park Chan-wook, who’s the director of Old Boy, and The Handmaiden and Old Boy was a big influence on The Sympathizer. So I feel that everything just worked out. He has the visual style, the political sense, the aesthetic sense, the understanding of colonialism and war to make this TV series. And when we got Park Chan-wook, we got A24, which young people love. Everybody loves A24. I mean, it’s such a hot production company. And then when we got A24, we got Robert Downey Jr. And we got Robert Downey Jr., we got HBO.

Kerri:

Wait a minute, is it a series or a movie?

Viet:

It’s a TV series.

Kerri:

Great.

Viet:

Seven episodes. We think it’s going to happen. And it’s done. They’re editing. We think it’ll air in April.

Kerri:

This is exciting. I’d read about it and then there seemed to be no news about it.

Viet:

By the way, I mentioned Sandra Oh and Robert Downey, Jr. Those are the actors you will know. But I do want to emphasize that everybody else, almost everybody else is Vietnamese. Okay? And for those of you who are Vietnamese, you will recognize Nguyễn, the MC of Paris by Night, our Hollywood. And Kỳ Duyên, our most famous South Vietnamese actress in there. But then everybody else are new actors. Hoa Xuande one day from Australia plays The Sympathizer, for example. And so the thing about a TV series versus a book is that if you write even a good or a great novel, you’d be lucky to sell 10 or 50,000 copies. If you make even a terrible TV series, you’re going to get millions of people to watch it. So whatever this TV series is, at least we will do something to center all of these Vietnamese faces, these Vietnamese bodies, these Vietnamese stories, these Vietnamese voices, and hopefully that will make some difference to Americans and people the world over, but to Vietnamese people as well.

Kerri:

And what about The Committed? I mean, come on. That’s cinematic too.

Viet:

The Committed. I sure hope so. But anyway, so I mean, it depends if the first season is successful. And if it is, then hopefully we will have a second season set in Paris. And it will not be like Emily in Paris. Okay?

Kerri:

Which I haven’t seen.

Viet:

Me neither.

Kerri:

Wait, is there anything… anybody up there? Come on you people in the balcony there, you have no questions? Really? All right, back down here.

Speaker 2:

Hi. I was so moved by your descriptions of your family, and it made me think about a friend of mine who is a refugee from South Sudan, and he’s sort of in the part of the refugee experience of working the 14-hour days and he’s driving Uber. And I guess I was curious what you think about the types of ways that this country could be set up to give people more time and space and not have to be in that zone of working, working, working? And just, I guess the sort of societal structure that we could offer? And then also on a personal level, how do we support people who come to this country in those kinds of circumstances?

Viet:

There’s a line in the memoir where I go, because my parents helped to gentrify downtown San Jose. And then they were gentrified out they were so successful. And the line from the memoir is, “The business of America is driving other businesses out of business.” We’re a capitalist country. So in fact, in order to answer your question about how do we treat refugees better, how do we ensure that they don’t have to do this terrible grind in order to survive? The answer is not about refugees. That’s the language of the refugee crisis. Refugees are a crisis. What do we do to help them? To solve them? What kind of dangers do they pose to our society? When in fact, what you just described is an American problem. The reason why refugees have to work like that is because Americans have to work like that. So how do we help refugees? We have to help ourselves. We have to build a society that is based on love and empathy and sharing and socialism, my God.

Because if we don’t do that, we actually are never going to be able to help your friend or all the other refugees because that’s exactly the experience of working class and poor Americans. And that’s where most refugees end up is in poor and working class neighborhoods. I don’t think they’re doing anything different than poor and working class Americans except they’re marked by their otherness because of their color, language, religion and so on. But their suffering is American suffering. So to alleviate refugee suffering, we have to alleviate American suffering.

Kerri:

I think we ought to note that when you write the word America in the memoir, you have the trademark symbol for it, which goes to I think what you’ve just described.

Viet:

I capitalize America every time the word appears-

Kerri:

Yes, you did.

Viet:

… and I do the trademark and I capitalize the American Dream and trademark it as well. And the reason why is because we as a country are completely brainwashed by the word America and by the phrase the American Dream. There is no innocent way to say these words because it doesn’t matter whether you say them ironically or unironically, the point is we all say it. And when we say it, what we do is we center the idea that we are the greatest country on earth and that we own America. I mean, we literally own America. We own the property and the land, but we also own the idea of America. That’s why all the other Americans from other American countries are so resentful whenever they hear Americans calling themselves, this is America. And the reason why I do that to the word in trademark is because every time you see the word America and American Dream, I want you to think twice about what that means.

Kerri:

Yeah, I did.

Viet:

And I think that it’s so hard for Americans not to think of themselves as the greatest country on earth. And that has terrible and pernicious consequences in so many ways. In reference to the previous question, if we’re already the greatest country on earth, we don’t have to do anything different to help other Americans. And if we’re the greatest country on earth, that gives us the right to do things like invade any other country when we want to or fire drone missiles into any other country when we want to, that’s our God-given right. If anybody fired a drone missile into this country, it would be an act of war and we would try to destroy them. But we get the right because we are America to do that to everybody else. And we don’t think about it twice.

Kerri:

I mean, you know how dangerous it is even for, well, especially for politicians to try to poke at the mythology of what America is. Even Barack Obama hesitated to do that, who could try to open up conversations about who we think we are and identity. He didn’t even mess with this idea of the greatest country on earth and the American Dream. I think we don’t want to hear it, right?

Viet:

Most Americans don’t want to hear it. Again, it doesn’t matter if you’re a Democrat or Republican, whether you say it unironically as a flag-waving American, or whether you say it ironically as a liberal who believes that we should be a multicultural country. Even when you do that, you still believe that this country as a multicultural country is better than every other multicultural country on earth. And in the book, I do say that the American Dream is a euphemism for settler colonialism. I mean, we wouldn’t have the American dream if we hadn’t colonized this country. And we are still, from the perspectives of indigenous peoples, colonizing this country. That’s a hard reality for many Americans to confront.

Kerri:

Question right up there on that side.

Speaker 3:

Hi. As a Palestinian son of refugees, I’m just wondering at what point do you think other writers and artists are going to have the bravery, the humanity to stop and say, it’s time to call for a ceasefire. It’s time to call for peace, not just in Palestine, but elsewhere. Do you think there’s a threshold that non refugees, that people that haven’t been suffering their whole life or haven’t known suffering through their parents or their family, do you think that there’s a threshold at which most people will start to just see what’s going on?

Viet: