Ahead of an Inprint Houston event, author Viet Thanh Nguyen shares that and other revelations from his new memoir for Houston Public Media

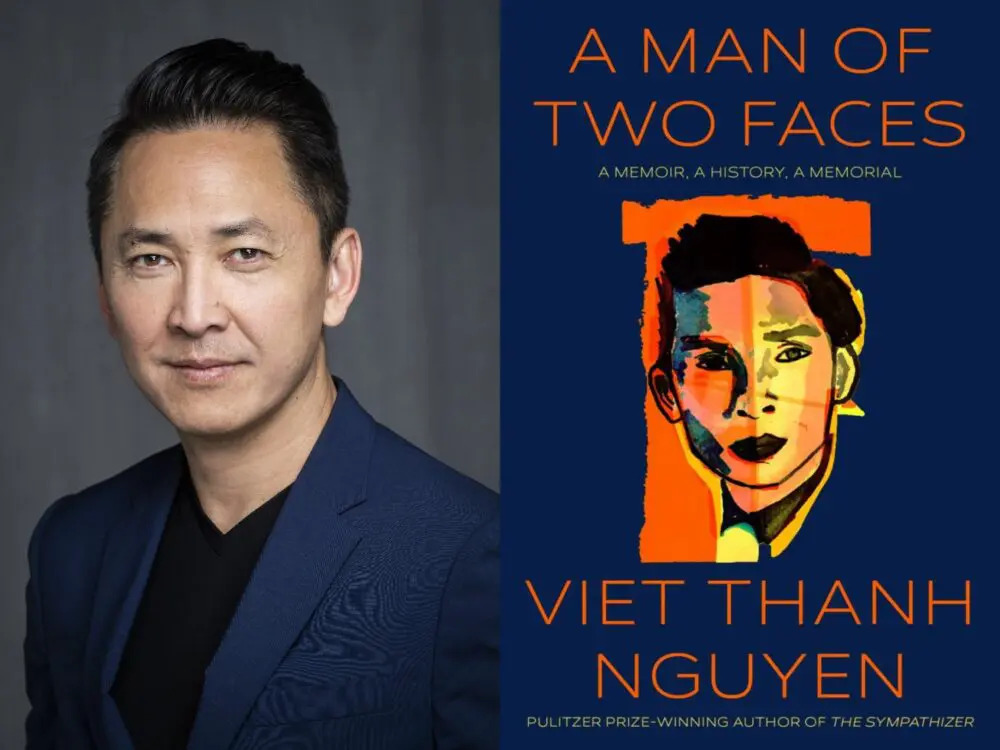

Issues of war – and the refugees it creates – are topics Pulitzer Prize-winner Viet Thanh Nguyen knows all too well. He came to the United States as a young child with his parents fleeing the Vietnam War. And that’s the subject of his new memoir, A Man of Two Faces, which he’ll discuss at an event with Inprint Houston on October 30.

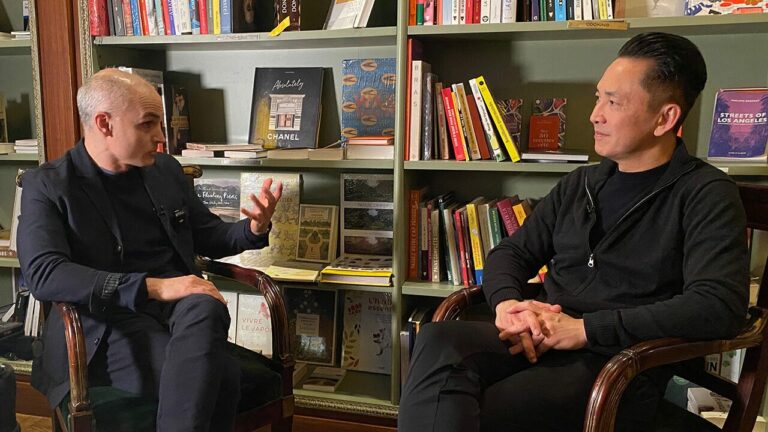

Nguyen won the Pulitzer Prize for his debut novel, The Sympathizer. In the audio above, in conversation with Houston Matters’ Michael Hagerty, the author says he was just four years old when he and his parents left Vietnam, and that he has no memory of his home country. He shares how he felt separated from Vietnam, as well as from his adopted home in the United States.

Read below for transcription.

Craig Cohen:

This is Houston Matters. I’m Craig Cohen. Last week, more than 700 writers called for a ceasefire in Gaza and an open letter published in the London Review of books. One of those writers was Pulitzer Prize winner, Viet Thanh Nguyen, who was supposed to speak later that week at 92, NY, formerly known as the 92nd Street Y in New York. It’s a 100 50-year-old Jewish organization. As NPR reported Tuesday, a few hours before the reading was set to take place, the event was canceled. Nguyen held an event at a Manhattan bookstore instead. That move, that postponement or cancellation, however it was characterized based on Nguyen’s criticism of Israel led some 92 NY staffers to resign. The organization tells NPR it’s pausing upcoming events while taking “time to determine how best to use its platform.”

Issues of war, and the refugees it creates are topics Nguyen knows all too well. He came to the United States as a young child with his parents fleeing the Vietnam War, and that’s the subject of his new memoir. It’s called A Man of Two Faces. He’ll discuss it at an event with Imprint Houston on October 30th. Nguyen won the Pulitzer Prize for his debut novel, The Sympathizer. In conversation with Houston Matters, Michael Hagerty, the author, says he was just four years old when he and his parents left Vietnam and that he has no memory of his home country.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

But I do remember the refugee camp that we ended up at Fort Indian Town Gap in Pennsylvania where there were about 22,000 Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees. And in order to leave the camp, we had to have Americans sponsor us, but there was no sponsor willing to take all four of us in my family. So one sponsor took my parents, one sponsor took my 10-year-old brother. One sponsor took me at four years of age, and of course at that age, I wasn’t really able to comprehend why I was being separated from my parents. So my earliest memories are of howling and screaming as I’m being taken away in confusion. And that was really where my memories and my idea of the country begins.

Michael Hagerty:

Yikes. That had to be so traumatic.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think that I thought it wasn’t traumatic. I think myself, along with so many other refugees who had been through so many things, and I’m not comparing my experience to what many other people have gone through, but I think for many people that I’ve known who are refugees, they’ve had to look forward in order to survive and not look back and to treat their traumas as something either normal or something that shouldn’t be spoken of. So for me, that was in my own way what I had to do as well is to pretend that that was just a fact of my life and that it was very minor because I was brought back together with my parents a few months later. But in fact, I think it did do some emotional damage on me, and I like to say that it gave me the requisite emotional damage necessary to become a writer.

Michael Hagerty:

Well, that’s handy, at least. You said your family was reunited. You grew up in San Jose, California. What kinds of realizations did you have about what America was then as someone who was growing up there and trying to figure it all out?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah. It was a very confusing adolescence for me because I was growing up in a very Vietnamese household. My parents liked to say that we were 100% Vietnamese, and I was also growing up in a Vietnamese refugee community. And yet at the same time, I couldn’t escape American culture because I was reading English language books. I was a total book nerd, comic book nerd. And I was also watching a lot of TV, that was all English, all the standard stuff that everyone else was exposed to in the United States. So I felt very American because of my education and popular culture, but yet also Vietnamese because of my home. So that was a real conflict and probably a very typical one. But in my case, I felt like in my parents’ household and Americans spying on these Vietnamese people in their customs and outside of my parents’ house among Americans, I felt like a Vietnamese spying on Americans. So that sense of duality, not unusual, but in my case, I took that sense of duality and I’ve infused it throughout my writing.

Michael Hagerty:

There’s so many stories out there of different ways that people experience versions of that, but feeling like you don’t belong in any one community. Some part of you does, but you don’t totally. You have one foot in, one foot out everywhere you go.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah, that’s very uncomfortable for a lot of people, for obvious reasons. I think many people would rather just feel like they’re always at home, that they completely belong wherever they happen to be. And I think that’s wonderful. That hasn’t been my fate, but as uncomfortable as that sense of duality often is for me, it’s also been very productive as a human being and as a writer. As a writer, of course, having a sense of duality means that I’m constantly aware of what other people are thinking, how they’re seeing, and I want to see through their eyes and feel what they’re feeling. And that’s very powerful for a writer. But I think it’s also very powerful for a human being to have that sense of empathy and that awareness that one’s point of view is not the only point of view out there. And that oftentimes we should be making ourselves uncomfortable by thinking about what other people are thinking and feeling and seeing. And that’s especially crucial in times of division, conflict and war.

Michael Hagerty:

Yeah. Imagine as a writer handy to have experience from more than one perspective. So you can write about both of those

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think absolutely. I mean, the business of being a writer, at least a prose writer of fiction and nonfiction is that you have to create characters. You can’t just be writing about yourself all the time, even if you may disguise yourself, you still have to create characters who are different from you. And sometimes that means creating characters who are very different in the sense of being of a different age or nationality or religion and so on. But I also think about how oftentimes the people who are the strangest to us are the people we live with, our parents, our families, or in the national context, the neighbors across the border. We are very familiar with our neighbors and our family, and yet this is sometimes where the deepest conflicts lie. So that capacity for empathy is something that is challenging for us to exercise for people who are far away in some circumstances, but also oftentimes quite challenging to exercise empathy for the people right next to us.

Michael Hagerty:

I know growing up you experienced some of the violent, darker aspects of life in America, your parents, namely on a particular Christmas Eve, what happened there?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I was nine years old and my parents had opened perhaps the second Vietnamese grocery store in San Jose. And that Christmas Eve, I was just home with my brother who was about 16, and I was doing what nine year olds do, which is watching cartoons waiting for my parents to come home. My brother gets a phone call and then when he finishes, he comes out and says to me, “Mom and dad, I’ve been shot,” and I didn’t say anything. I imagine now looking at my own children, if they were to receive news like that, how do you expect a nine-year-old to react to something like that?

So I think my reaction was numbness, shock, literally speechlessness. And my brother said, “Why aren’t you crying? Why aren’t you saying anything or doing anything?” And of course, that was also understandable for a 16-year-old to be equally perplexed as well. But I think for me, from what I took away from that was the sense that this is what our life was like. My parents were, thankfully, they only had flesh wounds and they were back to work the next day or the day after, and we never talked about it again. We all just had to live our lives, move forward, not look back, not talk about what it is that had happened to us.

And in order to cope, I don’t know, I can’t speak for my parents, but in order for me to cope, I just had to act as if all these things were simply a part of our normal lives. And it would take me a very long time to be able to confront what that violence meant for my family, certainly. But then also for the experience of Vietnamese refugees who had gone from a war torn country to come to the United States where many of them were also subject to further episodes of violence.

Michael Hagerty:

Yeah. I mean, what did that mean for your family or how did it shape how you or your parents saw life in America, how they operated from then on?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

My parents had been in survival mode their entire lives. They had been born in the 1930s in northern Vietnam. And what that meant is that they experienced 40 years of famine, colonization, warfare, and becoming refugees twice in 1954 and 1975. And they had relatively little education, and they basically worked their way up from very little as people with rural origins to becoming merchants in Vietnam and then losing all that and doing it all over again in the United States. So for them, I think it was survival, just work, work, work, believing God, sacrifice and have faith that everything will come out all right for themselves and their children and their relatives at home. And three out of the four of us made it, my father, my brother, myself. We made it in the sense that we’re intact physically and psychologically.

My mother was a heroic, brave woman. She was a wonderful soul. And then she went to the psychiatric hospital in 1975, soon after coming to the United States because her own mother died. Can you imagine being separated from your mother and not being there when she passed away? And then she went to the psychiatric hospital again when I was 18 or 19, and the third time when I was an adult, she went there and she never recovered. She was ill for 13 years after that, before she passed away.

So when I look at a fate like my mother’s, I think what happened was what happened to her simply what happens to any individual because of their psyche, their body, and so on? Or was she hammered by history and by everything she had endured. And my father had gone through many of the same things, but he didn’t end up in a psychiatric hospital. So I’ve spent much of my life thinking about questions of fate and history and how some of us are lucky and some of us are not.

Michael Hagerty:

This is Houston Matters. I’m Michael Hagerty. I’m talking with writer Viet Thanh Nguyen about his new memoir, A Man of Two Faces, which reflects on his experience coming to the United States as a refugee, fleeing the Vietnam War. He’ll be in Houston to discuss the book at an event with Inprint on October 30th. So for immigrants and refugees who may have gone through something very difficult or even traumatic to get here, why do you think there is often silence from the older generations about what they went through?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think silence is a major theme of Vietnamese refugee culture, but probably have a lot of refugee and immigrant cultures.

Michael Hagerty:

And human culture too.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Human culture as well, yeah. Well, I mean, for example, I mean, I’ve met quite a few children of American war veterans, and that’s also a common experience. Dad came home, didn’t talk about the war, and instead took it out on us. So I feel that history ripples through our emotions and our bodies, and if we don’t confront them, then the ripples continue through our children and our grandchildren. For refugees and immigrants in particular, I think there is certainly language and generational and cultural barriers because American raised or American born children are going to see the world differently than their parents and grandparents, and they’re going to express themselves differently. They want to be able to talk about things and their parents and grandparents may not, and I think the parents and grandparents may not because number one, they might likely have been deeply traumatized by what they saw or witnessed or did, and they don’t have a language for it.

Trauma and therapy and counseling, this is not a part of a lot of refugee and immigrant cultures. So people are just left to deal with their trauma on their own. So I think it’s not uncommon then for refugees and immigrants to suck it up and just feel as if, number one, even if they did talk about it, would these children understand who these alien children who are Americans basically, or if they did talk about it, would it just reawaken their own trauma? Or if they talked about what they went through to their kids and grandkids, would they just be passing on the trauma? So there’s various reasons why I think the people who survive these experiences may not want to talk about that.

But one of the unfortunate consequences is that the children and grandchildren are left in a state of befuddlement. Again, not understanding, not being able to articulate whether what they have gone through as children or grandchildren is unique to them and their families or is a product of history. And that is a very signature feature of peoples who have been through horrifying histories.

Michael Hagerty:

Writing stories down, writing a memoir might not be for everyone, talking about it might not be for everyone, but what did writing this and reflecting on all this do for you? Did you have any realizations about your own story or about your parents even as a result of putting this down on paper?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think for me, what I realized is that I don’t know myself. For example, the story I told about my mother going to the psychiatric hospital when I was in college, I wrote about that in college actually. And then that was so painful to write about it, put the essay aside for 30 years. And then when I picked it up and read it again in preparation for writing this book, I realized for the past 30 years, I’ve been telling myself, “My mother went to the psychiatric hospital when I was a child,” because that was how I felt, young and terrified. And then I read the essay and I realized she went to the hospital when I was 18. So even as an adult, my memory played tricks on me. My memory changed the story, changed the actual facts in order to protect me, I think.

So that realization led me to understand how deceptive memory is and how we can deceive ourselves very, very powerfully. And that is true not just for individuals, but for families, cultures, nations as well. The act of self-deception is constitutive of so many groups of people. So it was an important experience to write the memoir to excavate myself as deeply as I could. But also in writing this memoir, I really wanted it to be much more about my parents, or at least as much about my parents as about me. And everything I’ve told you has indicated how unique and extraordinary my parents were in overcoming so many things. But at the same time, I’ve talked to so many Vietnamese refugees and about their parents and their families, and the common refrain is they’ve all been through this. My parents’ stories are not extraordinary. They’re actually pretty typical of a lot of Vietnamese people of their generation.

So the book is about that too. And I don’t think acknowledging that somehow that my parents are typical rather than extraordinary, takes away from their story at all. In fact, I think it makes it deeper when we realized that an entire generation of people have gone through horrifying things and that this was normal for them and for their children and for their grandchildren. So I hope that in writing the memoir about my parents, I’m also writing about this entire generation of Vietnamese refugees and what they went through.

Craig Cohen:

Pulitzer Prize winning author, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s new memoir is called A Man of Two Faces. It’s about his experience growing up in America as a refugee of the Vietnam War. He’ll discuss the book at an Inprint Houston event on October 30th. He spoke with Houston Matters, Michael Hagerty.