Viet Thanh Nguyen entered a world immersed in restlessness and violence. The author was born in South Vietnam in 1971, years after his family fled North Vietnam. With the fall of Saigon in 1975, the family had to leave home behind yet again, moving into a refugee camp in Pennsylvania and later settling into San Jose, Calif., where his parents opened a Vietnamese grocery store—Andrew Dansby interviews Viet Thanh Nguyen for Houston Chronicle

Nguyen — who discusses the book with Houston writer Bao-Long Chu at an Inprint Houston event on Oct. 30 — took a different path, picking up degrees in English and ethnic studies and becoming a professor at the University of Southern California. In 2015, he released “The Sympathizer,” a novel of diligent prose and heady thematic content as the author probed issues of identity, war, displacement, colonization and assimilation. “The Sympathizer” earned Nguyen a Pulitzer Prize, followed by a MacArthur Grant and a Guggenheim Fellowship.

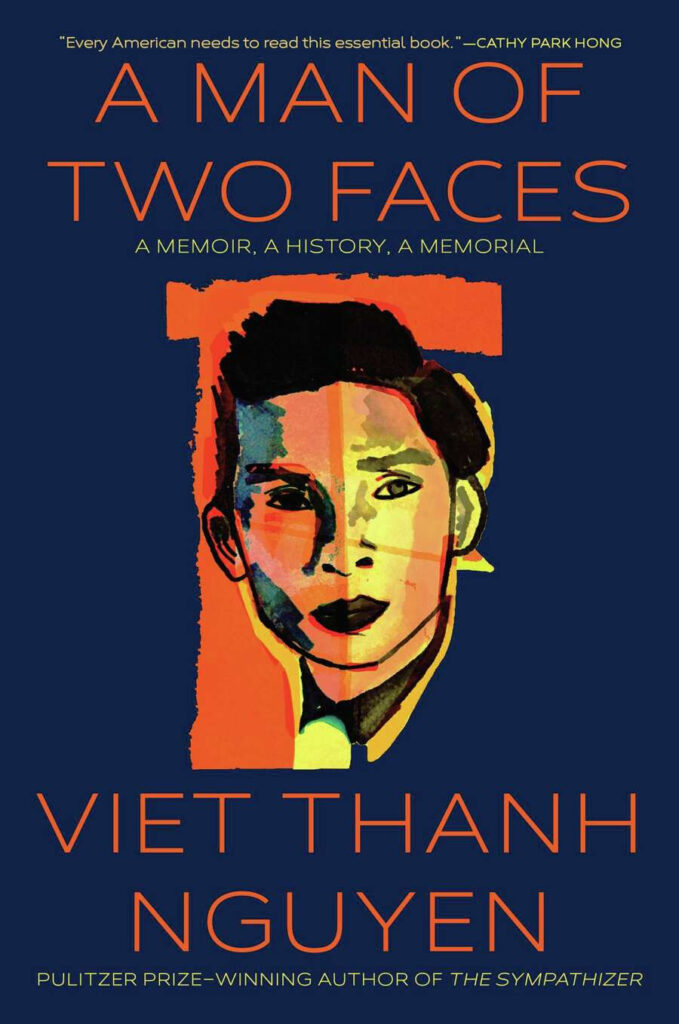

A sequel, “The Committed,” followed in 2021. Nguyen’s new book is “A Man of Two Faces,” which is aptly subtitled “A Memoir, A History, A Memorial.” The book feels like an updated counterpart to Ralph Ellison’s “The Invisible Man,” except Nguyen uses memoir instead of fiction to frame his story as a character who feels perpetually on the periphery. In “A Man of Two Faces,” Nguyen takes a fragmented approach to form, stitching poetic passages into longer, contemplative remembrances to tell a story about him, his family and two cultures twisted together through violent conflict and a barbed aftermath.

Q: True to the subtitle, there are so many pieces of this book that felt like they could’ve been the center of an independent book. The memoir, the history and the memorial to your parents. Was the editing process a labored one?

A: I knew I wanted it to move quickly and to cover a lot of material. Someone could write about the complications of American history, and it would’ve been a worthwhile project. But that’s been done. I was inspired by other forms besides historical writing. I’ve written a lot on Twitter. I read a lot of poetry. Those forms informed the quickness and the punchiness of it. The stylistic ambition of it was to not make the reader feel overwhelmed with footnotes and things like that. To make some poetic points. To provoke the reader into thinking and some poetic feeling.

Q: The sense of time in the narrative felt swirling, rather than set along a rigid line.

A: I think we’re conditioned, perhaps by our industrial lifestyles and watches, to think time is linear and forward-moving. Not just individual experiences but also collective and national experiences as we think of our history as moving toward some greater perfection. But when we’re freed from the watch and immersed in experience, it’s not linear. My life comes back to me in bits and pieces. So, there wouldn’t be linearity when I come in and construct a story about my past. Likewise, nations have a linear narrative. But between our noble and powerful ideals about democracy, freedom and exceptionalism, there are still these ugly sets of facts — conquest, genocide, exploitation — where another story can be true at the same time. We talk about history repeating itself: Those cycles exist because we haven’t resolved them.

Q: Did you feel more hemmed in writing in memoir form? I ask because with your novels, you can pour yourself and your thoughts into a character, but you also have great leeway with that character.

A: That’s a good question. A fictional character allows me to project my own disguised views through that character. To work in a memoir was a challenging experience. Part of the point of a memoir, to me at least, is learning that the hardest person to get to know is yourself. To get to know myself better, I had to do this mental trick for a while, which was to pretend I was a fictional character. To speak to myself using this voice of my own invention, the Sympathizer, to tell my story. Hopefully, part of the energy of “A Man of Two Faces” comes about from the same force that’s in the novels.

Q: We think of fiction as the place for an unreliable narrator. But there was a line — “You remember a kind man sharing milk with you or perhaps you just remember Ma telling you this story” — that made me think all of our personal narratives have a degree of unreliability, especially as time passes.

A: I think for many of us, until we’re forced to confront the possibility that we’ve made up facts and memories, we never question them. But our understanding of the past changes. We want our narratives to have cohesion. One thing in this memoir was me confronting how I’d deceived myself about my mother’s entry into a psychiatric facility when I was 18. But I left a paper trail. I wrote an essay about it when I was 19. Later on, I’d tell myself something else as an adult. But because I left this paper trail, 30 years later, I could look at that essay and realize this happened when I was a young adult. That I’d lied to myself. Not deliberately. But it was some form of self-protection. I could construct a case against my own false memory.

Q: This book made me think about that notion, perhaps one that needs revision, that there are two plots: man goes on a journey, and stranger comes to town. You’ve kind of absorbed both here.

A: Well, I think you got to something there. Certainly, I’m intrigued about the story of my arriving in the U.S. I was this stranger arriving, and then I went on a journey. The narrative of both is a story about being an outsider and then a quest to prove something. So the stranger finds out something about the stranger. The idea of a hero on a quest is about solving some external problem he can only do with some understanding of self that occurs on the quest. That’s what makes the journey so compelling. That’s why I called it “A Man of Two Faces.” An internal investigation took place. Not only through the heart of myself and my family, but also through Vietnamese communities and through the heart of the United States as well. We arrived as strangers, so I think we can tell America something about itself. There’s an insight you can only get from strangers.