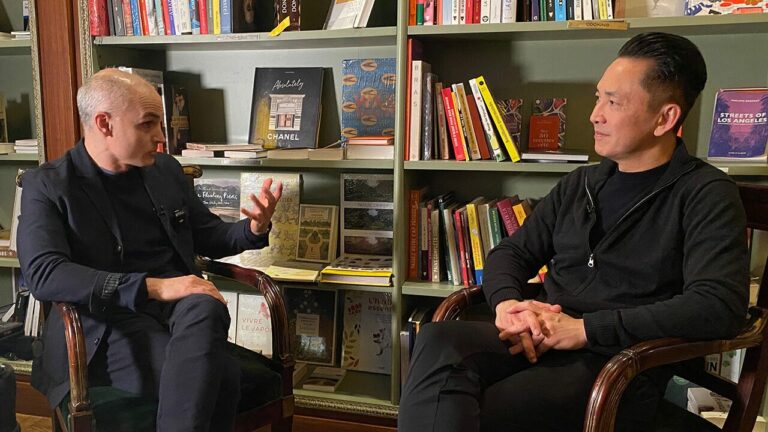

Pulitzer Prize winning author Viet Thanh Nguyen talks with CAAM’s Grace Hwang Lynch about his new memoir A Man of Two Faces. In A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial (Grove Press), Nguyen delivers a highly original, blistering, and unconventional memoir. He reflects on his own life as a Vietnamese refugee who eventually settles in San Jose, California. Reflecting on a youth shaped by images of Asian Americans, particularly Vietnamese Americans, on VHS tapes, Nguyen examines the role that Hollywood representation has played in shaping his consciousness and images a world where the stories of Asian Americans like parents are celebrated on the big screen. Nguyen also discusses the current state and history of Asian American publishing, his work in organizing the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network (DVAN), and the upcoming HBO Max series based on his Pulitzer-Prize winning novel The Sympathizer for the Center for Asian American Media

read below for transcript

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Hi everyone. I’m here with Viet Thanh Nguyen, the author of A Man of Two Faces. You may recognize him from his book, The Sympathizer, and he was also one of the experts in the CAAM funded Asian Americans documentary series on PBS. So thank you for joining me, Viet. It’s really great to see you and just wanted to see how it’s going for you to start off after your memoir has come out for about a week.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Hi, Grace. Great to be here with you. How it feels, it feels hard. I mean, this is a memoir and most memoirs deal with very personal things as this book does. It was difficult to write and it’s difficult to talk about because it requires going to a space of great vulnerability, which I’ve learned how to do a little bit over the last couple of years as I wrote the book. And now I’m learning how to speak to people about some very intimate subjects, both about my family and myself, but also about the country as a whole.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Yeah, I was particularly really interested in reading your book because I also grew up in San Jose around the same time as you did. I went to Berkeley, I took creative writing classes for Maxine Hong Kingston, and there were a lot of things that I felt were very resonant with me and then also a lot of things that were very different. And I think that this really dovetails with the idea that you’ve spoken about a lot about narrative plenitude and that idea of just having so much diversity within the Asian American population.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Sure. I think all Asian Americans are familiar with the opposite of narrative plenitude, which is narrative scarcity, which is when there are very few stories about us or whoever our group happens to be, whether that’s Vietnamese American, Asian American, and so on. And narrative scarcity is completely related to economic scarcity and the lack of political power and representation that Asian Americans have experienced over the last 150 years or so.

But we’re reaching a point where it seems like in certain places we’re starting to achieve some kind of narrative plenitude as Asian Americans in the subgroups. And I think literature is one of those places where there’s been a real explosion of Asian American writing in the past 20 to 30 years. And so now there’s a multiplicity of voices for Asian Americans as a whole, but also for particular groups like Vietnamese Americans as well. And so this book, A Man of Two Faces is certainly my story, my family’s story, but it’s also one version of the Vietnamese refugee and Vietnamese American story. Not to say that it’s all versions, but it’s one version of what it was like for myself and my family to come as refugees to the United States in the 1970s and to struggle with all the typical cultural, political, economic problems of the 1980s and 1990s for new Americans.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

When did you know you wanted to write a memoir? Because you said, we talked about how difficult it is to write memoir, and you’ve written other kinds of books, you’ve written a novel and several novels, short stories, academic writing, so why do memoir?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think I’ve been warming up gradually to the idea of writing autobiographically. The origins of this book were in Berkeley for Maxine Hong Kingston’s seminar in 1991 when I was only about 20 years old, and it was an autobiographical essay about my mother going to a psychiatric facility. A very obviously terrible experience for her, but also difficult for me to witness. Then that was so difficult to write about, I put it aside for 30 years. In between, I did write little bits of autobiographical things and various kinds of essays and a short story and so on. And so I think I warmed up gradually over 30 years to feeling a little bit more comfortable writing autobiographically and then finally feeling that there was a narrative here, a story big enough for a whole book, certainly for me to grapple with what happened to my mother and to grapple with other questions about what happened to Vietnamese refugees in general. Because I think one of the things about my mother’s story, which is a very dramatic and epic story, is that she lived an extraordinary life to someone like me.

But when I compare her to other Vietnamese women of her generation, she probably lived kind of an ordinary life in the sense that many, many, many people of her generation, men and women, went through horrifying experiences. And I don’t think it lessens my mother’s story or anybody’s story to say that their struggles and so on are not extraordinary but ordinary. Because what that means is that they come from a whole group of people who are shaped by history, and the book deals with how do we draw the line between how we’ve been shaped by history and how we’ve been shaped by whatever is unique to us. And there’s a mystery there about trying to figure out our unique place relative to our individuality, but then also to this history that binds us all together.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Yeah, that’s definitely something, I don’t know if it’s something that Asian Americans particularly are always parsing what is unique to our own families or just our own particular uniqueness and what is a result of things that happen to our group. And then there’s the idea that also you talk about very much the theme of how you see people like yourself portrayed on movies and on the screen, and there’s kind of recurring sentence that you have. Something like, if a movie was made of my family, dah, dah, dah, dah, dah.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I grew up pretty much like everybody else watching movies and television shows in the 70s and 80s and seduced by the power of television and movies, but also by the power of books and stories. So in general narrative. And for me, I didn’t see myself in much of what I was watching or reading, which is not in and of itself a problem. I think that the power of art is that it should be able to speak to people who are very different from the creators of that art. So the fact that Jane Austin or Charles Dickens or Percy Shelley could speak to a Vietnamese refugee boy in San Jose, California is amazing. They weren’t thinking about Vietnamese refugees, and they shouldn’t have to. And the inverse applies, which is that us as Asian American storytellers, we don’t need to worry about whether people in England or India or Russia or whatever are going to read our work. We hope that if we create a beautiful enough work of art, it will speak to people everywhere.

That being said, there is also a dimension of seeing ourselves in narratives not made by us, in which we appear in ways that we don’t even recognize. And of course, these are racist, sexist stereotypes and the like, which are very common in the depictions of Asians and Asian Americans in mainstream media. And so I encountered that as well, and that shaped me very fundamentally because what I realized eventually was that growing up as this refugee in San Jose, California, I was saved by stories because I went to the public library, I read enormously, and that was my way of soothing myself or dealing with the traumas of the refugee experience that I watched my parents go through.

And then I was watching movies like Apocalypse Now and many other kinds of movies in which the Vietnamese and other Asians are depicted terribly. And I felt the power of stories to destroy me because I think these images were not just stories, and this is part of what it means to talk about narrative scarcity when almost none of the stories are about you, when images about you actually appear, they take on out-sized meaning. And this is a very common Asian American experience: destroyed by an image. And so I really do believe in the power of stories, but when we talk about stories being powerful, we have to acknowledge both dimensions, the salvation and the destruction. And so this book is very much about recording or talking about what stories did to me, but the book itself as a story is my attempt to grasp some of that power to save and to destroy through our own story.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Yeah, it almost seems like some of the passages where you’re referring, you refer to a lot of movies from the 70s and 80s that were just really awful depictions of Asians and also really shaped people who grew up during that time because those are the references that your classmates and the kids at school have, and they think that that is reality. And it seems like you’re rewriting some of those narratives in your references to them, and then also your kind of imaginations of what this movie made of your family might look like.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

One of the motifs, as you mentioned, is this idea that my parents’ lives are worthy of epic movies. And again, going back to this idea that they’re not extraordinary, they’re ordinary. What that means is your parents’ lives, the lives of so many other people of the prior generation who were immigrants or refugees from Asia, they’re all worthy of having stories and movies made about them. But of course, there are very, very few. And one of the jokes in the book is even if there was a movie made about people like my parents, it would probably be an indie movie made on a shoestring budget. But part of the point book is to imagine what life would be like if we as Asian Americans or any other population that’s rendered as a minority, had the power to tell our own stories with the most lavish means possible. And it’s not that that’s the most important thing.

I think poems, novels, memoirs, which are written for very little money and cost only the writer’s life, those are enormously important. But there is something about a $200 million Hollywood blockbuster that has an enormous impact as we’re well aware, that has a global impact. And so that’s not the only way to tell a story, through a Hollywood epic, but we know that that does transform perceptions. And of course, when we look at the landscape today, we have this glimmer of hope that maybe we’re starting to see Asian American access to these modes of production and representation. But we’re still a long way from white people because white people own the means of production and representation.

Right now, Asian Americans are finally getting to be actors and directors, but they mostly do not own the means of production and representation. So our struggle for representative equality and for narrative plenitude is not just about representations and stories. It is tied to a larger project of emancipation, about us having full economic political rights and opportunities as white people. And I think that’s one step along the way. There’s a more utopian vision beyond that. But I think the idea that we sometimes talk about in terms of representation matters is important, but it’s not enough. And with what you do in CAAM and what I do with my own arts organization, Diasporic Vietnamese Artist Network, these are efforts to not just tell stories, but to create the conditions for storytelling for others.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Absolutely. And now you also have an opportunity to put your story on TV with your adaptation of The Sympathizer. Can you talk about that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

It’s not my adaptation. It’s not my TV series. It’s our TV series at best, or their TV series at worst. But I have high hopes for this collaboration between myself, director Park Chan-wook who I think many people know, A24, which has huge numbers of fans and HBO, which is this gigantic behemoth, that this collaboration in the adaptation of the TV series for The Sympathizer can have an impact. Because even a good novel would be lucky to sell tens or hundreds of thousands of copies, and even a bad TV series could reach millions of people. So I’m hoping that it’ll be a good or very good or an excellent TV series.

The collaborative process has been really wonderful for me as an executive producer on the series, and as someone who’s read the scripts and given feedback and been on set a few days and has had conversations with Director Park about his vision for the movie. But it is a collaboration, and it is a collaboration that involves literally hundreds of people and tens of millions of dollars. So it’s way beyond what it means to write a novel. So that’s why I have to have a certain amount of hope, but also humility in the face of this process.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Well, I’m looking forward to seeing it. I mean, it sounds very, very promising. And you mentioned that definitely in the last few years we’ve seen a lot of Asian American memoirs, and it seems like in the past year and particularly quite a few Vietnamese American memoirs. Why do you think that is coming together at this moment?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, in fact, I think we’ve had a memoir as a key part of Asian American writing for a very long time. If we go back to Asian American literary history, the first …

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Maxine Hong Kingston, like we talked about.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I’m talking about late 19th century. You go back to the Eaton Sisters, Ana and Sui Sin Far, Sui Sin Far wrote, I think, oh, [inaudible 00:13:50] was the first Asian American writer writing in English. And one of her early books was her memoir, Me. And so we’ve been doing it for a long time. So I don’t know if there’s been a boom of memoir in particular. It’s just that memoir has always been a key component of Asian American writing through the 20th century. But I think for Vietnamese Americans in particular, one of the earliest books in English was Le Ly Hayslip’s When Heaven and Earth Changed Places, which became Oliver Stone’s Heaven and Earth. But yeah, I think that the younger generation, people my age, not too young, but younger generation, it takes a while to build up the wherewithal, the confidence, the ability, the emotional ability, the writerly ability to write a memoir. So maybe that’s why we’re seeing more of these Vietnamese American memoirs of the 1.5 Generation. It’s taken a few decades for us to process everything that’s happened to our families and community.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

What about DVAN? Diasporic Vietnamese Artist Network? I would think that collective community has played a role in that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I sure hope so. The roots of DVAN go back to Berkeley in the early 1990s when I was a student there and my fellow Vietnamese American artistically inclined friends, and I looked around and didn’t see a Vietnamese American arts organizations so we started our own. Melodramatically called Ink and Blood. And over the decades, it evolved gradually into the Diasporic Vietnamese Artists Network, which now nearly 30 years later is a 501(c)(3) with staff and budgets and things like that. But the impetus behind that organization again was this idea that while it’s absolutely crucial that artists do their work individually and so on, it’s also important to foster a community of artists so people don’t feel alone. And also to foster opportunities for a new generation of writers and artists. And I think that’s what DVAN has done in a variety of different ways. And I’m particularly excited about how we are building new communities. We just did a residency in France where we brought 10 Diasporic Vietnamese writers from all over the world to [inaudible 00:16:00].

Grace Hwang Lynch:

That’s amazing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Yeah. And built new relationships and hopefully are also helping to transform the French literary landscape because this idea of organizing or cohering around an identity is not popular in France. We have Vietnamese American literature here, Asian American literature, but in France you don’t have that kind of a thing. So all of a sudden now there’s Diasporic Vietnamese writing in France, and the French writers of Vietnamese descent are like, “Wow, that’s actually not a bad thing.” So I have high hopes for the future for those kinds of collaborations. But then also we’re opening opportunities I hope for people who are very young in their 20s and 30s. And you talked about how we share this bond of growing up in the 70s and 80s, being exposed to these horrifying movies and things like that. I think people of a younger generation may not have that experience, and thank God they don’t have that experience, but they have a different generational experience.

They’ve seen different kinds of Asian and Asian American representations. They don’t necessarily have the same hangups about war, refugees, the immigrant experience. And I think that’s a good thing. And I don’t know what that means because it is a different generational experience. So I think the task of an organization like DVAN, maybe for CAAM and other arts organizations is not to dictate what a new generation does, but to provide the opportunities and the networks and the spaces and resources for them to do what they want to do and will see a whole new set of visions arise. And that will hopefully point us in a new direction.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Great. Is there anything else you’d like people to know or would you like to say anything about what’s happening next for you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I mean, A Man of Two Faces. I gutted myself to write that book, but I think it’s actually kind of fun to read from everything I’ve heard because there is quite a bit of humor in the book. And I was thinking of Anthony [inaudible 00:17:51]’s after parties, the short story collection where he says, he talks ironically about the sob stories that Asian immigrants and refugees and …

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Trauma. The trauma stories.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

They’re obligated to tell. And so there’s a lot of that in this book. But he’s very humorous about talking about the sob stories. He’s very ironic. And this book too, likewise, ironic and comically aware of what it means to be an immigrant, a refugee telling these kinds of stories. So much so that I summarized a plot of The Sympathizer in one star reviews from amazon.com because there are a lot of haters out there and I’m perfectly fine with that. But what else is coming up? I have a children’s book coming out in April called Simone with the artist, Minnie Phan. It’s her idea about a Vietnamese American young girl confronting wildfires. And I took that idea and I wrote a whole story about it. Minnie’s illustrations are incredible. It’s a beautiful, beautiful book. And I’m actually very, very excited for that to be my next book.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

That’s great. And maybe that’s the story that our children’s generation, those may be more defining crises of their lives as Asian Americans rather than some of the stories of arrival and homeland stories that maybe shaped our lives or our parents’ lives. So that’s really interesting.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Sure. Trading one horrifying experience for another horrifying experience.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Yes, I guess so.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Grace, it’s been great talking to you. Thanks so much for hosting me.

Grace Hwang Lynch:

Yes, thank you so much, Viet. Good luck with everything.