Viet Thanh Nguyen discusses Nothing Ever Dies and his personal experiences in this interview for the History News Network.

The troubling weight of the past is especially evident when

we speak of war and our limited ability to recall it. Haunted

and haunting, human and inhuman, war remains with us

and within us, impossible to forget but difficult to remember.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, Nothing Ever Dies

The people of Vietnam and the people of America see the war fought in and over Vietnam very differently. For Americans, it’s the Vietnam War and for the Vietnamese, it’s the American War.

The United States lost about 58,000 troops in combat and was left with a nation politically torn asunder. But the war also left three million Vietnamese troops and civilians dead as well as killing nearly one million Laotians and about two million Cambodians when figuring in those Cambodians lost during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime. Many more were wounded and displaced. And much of Southeast Asia was devastated by the machinery of the war, by the bullets and bombs and chemicals and savage workings of modern, large-scale, industrialized military operations.

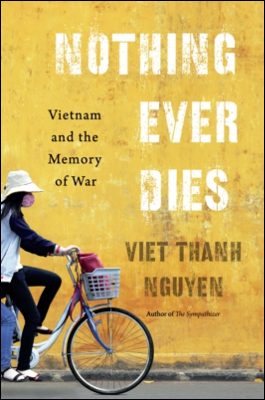

As Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen stresses in his new book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (Harvard),those losses of millions of people in Southeast Asia are largely ignored in the American version of events. Yet, he explains, the war in Vietnam is remembered primarily and uncharacteristically from the perspective of the losers, from the viewpoint of the Americans who possess the industry and power to put out their version of the war to the world. When it comes to the memory of the cruel war in Vietnam, the U.S. won that battle.

In Nothing Ever Dies, Professor Nguyen explores how the Vietnam War is recalled and commemorated in Vietnam, America, and beyond while reflecting on the ethics of memory: who tells the story of the war, how is the story disseminated, what is just memory, why the inhuman must be recalled with the human, and how war in general is remembered—and often forgotten. He reminds readers that all wars are fought twice—first on the battlefield and again in memory.

In his rigorous study, Professor Nguyen examines how the war shaped his own life as a Vietnamese refugee as well as the lives of his refugee parents and survivors on both sides. He also critically assesses the art, culture, literature, film, artefacts, memorials, cemeteries, and other manifestations that came out of the Vietnam War from both the United States and Vietnam.

While dealing with weighty ethical and cultural issues, Professor Nguyen planned Nothing Ever Dies for a wide readership, and his writing was informed by his award-winning fiction.

His novel The Sympathizerwon, among many awards, the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Literary Excellence from the American Library Association, and the Edgar Award for Best First Novel from the Mystery Writers of America. The Pulitzer Prize Citation read, in part, “A profound, startling, and beautifully crafted debut novel, The Sympathizer is the story of a man of two minds, someone whose political beliefs clash with his individual loyalties. In dialogue with but diametrically opposed to the narratives of the Vietnam War that have preceded it, this novel offers an important and unfamiliar new perspective on the war: that of a conflicted communist sympathizer.”

Again, with Nothing Ever Dies, Professor Nguyen brings a new perspective to the Vietnam War while considering memory and war and trauma as he reflects on the humanity and inhumanity of the humans on both sides of conflict and the inequities in who tells the story and who listens.

Professor Nguyen is the Aerol Arnold Chair of English and an associate professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. In addition to Nothing Ever Dies and The Sympathizer, he is the author of Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America, the co-editor of Transpacific Studies: Framing an Emerging Field, and his articles have appeared in numerous journals and books. He is also an acclaimed short fiction writer and his next book is the short story collection The Refugees, forthcoming in 2017. He was born in Vietnam and raised in America from age four.

Professor Nguyen generously talked about his background and his new book by telephone from his home in Los Angeles.

Robin Lindley: Did a specific incident spark your new book of reflections on the Vietnam War and how we remember war, Nothing Ever Dies?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: It took about nine years to do the research for the book, and about a year to write the book. I wanted to write the book and tell a story.

There wasn’t a single incident that got it started. It was really my experience as a refugee from Vietnam who became Vietnamese American and grew up caught between the history of the war seen by Americans and the history of the war as seen by Vietnamese. I tried to make sense of these different versions, both of which have their strong suits and shortcomings. I wanted to come up with a way to account for memory of the war in which you have these historical viewpoints.

Robin Lindley: Did you have an initial plan for the book? How did the book evolve over the years?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: I didn’t have a plan for the book. I threw myself into the research for those nine years with field trips to Southeast Asia and writing articles that explored theoretical questions that were of interest to me.

The real plan for the book came about when I finished writing The Sympathizer. Then, I finally had the time to turn back to this big project, Nothing Ever Dies. I could have just collected the essays I had written and added an introduction and conclusion and called it a book, but that would have been inadequate because those essays reflected snapshots of my thinking over the years and they were very academic.

I wanted to write a book that would be coherent from beginning to end and that would appeal to non-academics as much as academics. The plan was simply to tell a story.

After all of this research, when I sat down to write the book over a year I knew that I would divide it into three parts and that there would be a symmetry to them with three chapters per part, and that it would begin with memory and with forgetting. That was the only outline I had and I just literally started writing each chapter from the first page to the last page without an outline. I wrote each in about a month and they have a narrative flow.

Robin Lindley: So your fiction writing informed the writing of Nothing Ever Dies?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: Absolutely. I learned how to tell a big story through the novel. When it came to Nothing Ever Dies, I trusted my intuition that I could depend on these storytelling skills, which I didn’t have during those nine years when that I was doing the field work and the research. Writing those academic articles was a real struggle and I [had to find] the story I was going to tell. I spent so much time thinking about the project and the ideas, that when it came to writing Nothing Ever Dies, most of the ideas I had already processed so it was just a matter of telling individual stories in each of those chapters and that was relatively easy.

Robin Lindley: It’s a powerful book of reflections on war and memory and what happened in Vietnam. At the beginning of your book, you state that you were born in Vietnam but made in America, and you describe through the book ways that the Vietnam War has shaped your life. You arrived in America in 1975 when you were only four years old and you were immediately separated from your family to live with a host family.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: That’s right. I lived with them for a summer.

Robin Lindley: Do you have any memories of Vietnam?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: I have some fragmentary, episodic memories. I have no idea if they are reliable or not. They’re just images and I can’t trust their authenticity. Really my narrative memory begins in the refugee camp in Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania. My ability to begin to think about my own past begins through that traumatic experience.

Robin Lindley: What do you recall about the camp and living with your host family?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: What I recall about the camps are barracks. It was probably not a difficult time for a four-year-old but it must have been a difficult time for my parents. It was probably fun for me because I was still with my parents.

The difficult part for me was being taken away from my parents and sent to live with two sponsor families. That was emotionally devastating. I had no idea why that was happening.

The first sponsor family I was sent to didn’t know what to do with me. And I was four years old. I was probably screaming and crying a lot. I have a three-year-old son right now. If he gets separated from me, he could throw a fit. I can imagine how difficult it was for this sponsor family, a young couple, to deal with a little stranger who couldn’t be soothed.

Then I was moved to a second sponsor family that had other kids and I think they were probably better equipped to handle someone like me who was four years of age. But I was still missing my parents and was cognizant of the fact that I was a guest in this household. I remember being taken once to see my parents. They were living in an apartment. I had to leave, and I was screaming my head off as a result.

Robin Lindley: How long were you separated from your parents?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: A few months. We arrived in the camp in May 1975 and, by the fall, I was back with my parents.

Robin Lindley: Was your father a combatant during the Vietnam War?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: No, my parents were merchants and my father did not have to serve in the military.

Robin Lindley: How did they survive the war and make their way from Vietnam? They must have left at the time when Saigon fell.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yes. My parents are smart, pragmatic people who are good at business. They were actually able to thrive economically during the war, which other southern Vietnamese people could do too given the war economy. They escaped Vietnam during the last months of the war, in March and April 1975.

My mom, my brother and I were living in our town of Ban Me Thuot in central Vietnam in March 1975 when the final invasion happened. My dad was in Saigon on business, and we were cut off from my dad. My mom had to make this life or death decision on her own to flee our town after it was seized by the Communists and walk downhill with many other refugees from this highland town to Nha Trang , which is a seaside port, a journey of about 150 kilometers that was not an easy trek. We grabbed a boat from Nha Trang to Saigon and found my dad. Within a month, the Communists took Saigon too. We fled on the last day out of Saigon on a barge.

Robin Lindley: That’s an incredible story. You mention that the war is still very alive for your parents.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yes, I think it’s alive for everybody who was old enough to remember that experience. I have not met a single Vietnamese American who lived through that time with a conscious memory who isn’t deeply marked by those days in some ways.

For my parents, they were forever distrustful of Communists. They didn’t like Communists before, and they certainly didn’t like them after 1975. They were trepidatious about returning to Vietnam, but they did so in the early nineties at a time when relations were re-established between the two countries. They didn’t like their two visits back because Vietnam was still a poor country in the nineties. And my parents had a huge emotional and financial burden supporting many of their siblings in Vietnam from the 1970s through the 1990s. After the second visit, my dad over Thanksgiving said, “We’re Americans now.” He had never said that before.

Robin Lindley: Your writing on memory and war is remarkable. I’ve talked with historians and even some neuroscientists about how we remember traumatic events. Do you think we somehow inherit the traumatic memories of war from our parents?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: There’s a hypothesis that memories can be physically carried in the body. That’s something creative writers have always suspected—that somehow the body retains memory in a metaphorical way and a physical way.

I can clearly see that second generations can inherit the memories of the generation that preceded them if the story has been articulated. For example, if the story has been told in an explicit way, that memory can be carried.

Also, memories are particular. They can be sedimented into the ways people behave and into the ways they treat other people in the family and even in silence. All of these things shape family interactions and shape characters.

People I think do inherit memories even when they don’t know they do. Sometimes they do know it and often that history becomes a reflex that’s manifested in how people behave in families and treat each other badly or refuse to talk about certain things. This is a way trauma, even if it’s not horrible, can influence people’s lives.

Robin Lindley: My father survived horrific combat and serious wounds as a soldier in New Guinea in World War II. My mother once said he never wanted a son because he feared a son would have to go through another war. I was subject to the draft during the Vietnam War, but ultimately did not have to serve.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: As with the example of your father, I certainly have heard of many instances of children wrestling with the silences of their military fathers usually. They go on a quest of what their fathers experienced because they know there were experiences that somehow shaped their own lives even if their fathers never talked about them.

Robin Lindley: In your book, you stress that the United States, the loser of the war that shaped your life, has told the world its story of the war rather than the victors who usually supply the story of most wars.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: It goes in two directions. The wound to the Vietnamese here is partially self-inflicted. In 1975 they had a moment of triumph that most of the rest of the world admired and they had a great degree of goodwill and they really bungled that with their postwar policies. They lost the moral legitimacy that they were so good at acquiring during the course of the war. That undercut the power of the Vietnamese revolutionary story.

But then they were also up against this massive American machinery: the military-industrial complex and its corollary of economic embargo and the power of the American culture industry including Hollywood. All three of them worked to contain the Vietnamese capacity to transmit their story in whatever fashion. At the same time, America promulgated and propagated their version of the past through channels that the rest of the world was familiar with, and most obviously Hollywood.

Although some of us may sneer at Hollywood for the kinds of stories that it tells or the individual movies that it produces, collectively the power of Hollywood is significant in achieving popular perceptions of history. We have the Hollywood version of the Vietnam War, which is seen over the world including in Vietnam.

When I mention the history of the war, people inevitably ask have you seen this American movie or this other one, typically Apocalypse Now or Platoon. I would always run into American memories of this war and try to combat them because they were so prominent in people’s understanding even if these people opposed the Vietnam War. Even if people disliked the role of America in the Vietnam War, their understanding of that role is shaped by American pop culture.

Robin Lindley: Many people don’t realize the cost of the war. We lost 58,000 and that loss still haunts us. But three million Vietnamese, many of them civilians, died in the war. In the book, you note that the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., is 150 yards long, and a similar memorial to the Vietnamese dead would be nine miles long. That’s truly staggering.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: I hope that’s correct. I got that figure from the Welsh photographer Philip Jones Griffiths, a well-known photographer during that time.

Robin Lindley: You stress that the United States had the power and the machinery to put out its version of the Vietnam War.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: The terrain of memory between the Vietnamese and Americans is completely related to the machinery of the war itself.

One of the great ironies of this great ironic war is that you had three million Vietnamese dead and 58,000 American soldiers dead. The American capacity to inflict that asymmetrical damage on another people is directly connected to the American ability to also wage an asymmetrical war of memory, to foreground that memory of 58,000 dead and erase the memory of the three million dead.

Many Americans are aware of American losses and unaware of the scale of what Southeast Asians went through. That’s what it means to live inside a military-industrial complex, or to live inside a war machine that you accept so you accept the narrative put forth by this complex or this machinery.

Robin Lindley: What do you mean when you use the term “weaponized memory?”

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: Memory can be turned into a weapon in a military-industrial complex. The memory of this war can be turned into a weapon, by Hollywood for example, in terms of ideologically persuading Americans and the rest of the world to see the history of this world in this fashion. Then that prepares Americans most particularly to think in a certain way that makes them ready to fight another war or to accept the fighting of another war.

If you look at the Vietnam War and the subsequent wars the United States has fought after that, you have to take into account not just the military-complex itself, but you have an ideology that operates and, in that case, the use of memory to support military endeavors overseas is crucial.

The United States government has been working hard to control the memory of the Vietnam War in certain ways, and that works in conjunction with how culture reflects a similar effort.

Robin Lindley: It seems we’re in a kind of “Forever War” now in the Middle East, and you trace our imperialistic conflicts back to the 1898 war we waged in the Philippines. And war continues now in Iraq and Afghanistan. Have we learned lessons from Vietnam?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: The lessons out of the Vietnam War for Americans have been two-fold with positive and negative lessons.

In the two or three decades after the Vietnam War, the negative lessons prevailed. It was seen as a bad war that was divisive for Americans and imperialistic in its conduct overseas with a devastating effect on Southeast Asians. The lesson was that the United States shouldn’t get involved in offensive wars and shouldn’t be in other countries in this fashion anymore. The negative lessons were the result of popular perceptions and memories of the war.

There were also positive lessons in that American policymakers and the military who looked at this war recognized it was a failure for the United States. But they looked at it to figure out how not to repeat those mistakes. By that, they didn’t mean not to go into other countries but how to develop policy and strategy to overcome obstacles. This idea that there can be a positive lesson extracted from the failure of the Vietnam War to rehabilitate the American military and American foreign policy has now become prominent to the government and the military and is persuasive to the general American population.

Robin Lindley: You also use the term “restorative nostalgia.” That may apply to the Trump campaign and the idea of making America great again—whenever the greatness was—maybe a time before the Civil War for his supporters.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: That’s not my idea. It was the idea of Svetlana Boym in her book The Future of Nostalgia. Reflective nostalgia is looking at the past with the irony that we know we can’t simply return to a Golden Age. Restorative nostalgia is the belief that we can restore that Golden Age. It’s a dangerous kind of nostalgia obviously because in most cases we can’t get back to that age. I think that figures like Trump play on that idea that there once was a better time period and if we do certain things we can restore that history. It’s not unique to the United States but it certainly arises whenever there are moments of crisis and transformation as we have right now.

Robin Lindley: There seems to be an American tendency to forget our history and perhaps look forward while ignoring the past. What do you hope historians take from your book on war and memory?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: It’s interesting to me that historians have been reading this work and receiving it well so far. I don’t quite have the words to speak about it because I never thought I was writing a historical account, but it seems some historians think I have written a historical account, which is great.

I’ve learned a lot from reading historians. As a literary critic, I work in a field that doesn’t tell stories whereas historians, at least a certain stream of them, haven’t given up on telling stories. I have learned a lot from the historians’ ability to tell a narrative. In turn, I hope that I’ve brought certain historical sensibility about storytelling as well as a literary critical sensibility to it—an awareness of how it is that ethics and aesthetics and industries play a role in shaping stories both in terms of how these issues are critical to a storyteller but also in terms of how they shape the conditions of production and reflection for stories.

I divided the book into three sections, ethics, industries and aesthetics, because I think each of them are inadequate in terms of accounting for how we remember, but each of them is absolutely necessary. So, the book isn’t just about the ethics of memory, for example, but it’s also a book that draws attention to how ethics are shaped by industrial and economic conditions and how the way that we tell stories and how we receive stories—in historical accounts too—are shaped by our sense of aesthetics. All three of these things are in play and affect our capacity to both understand history and to tell history.

Robin Lindley: And you stress that the weak and the poor are often voiceless or don’t have a significant role in determining our memory while there’s also unequal access to the tools and industry of memory in our society.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yes. Those political concerns have always been important to me. I haven’t been able to separate my scholarly work from my aesthetic work or from my political concerns.

I have been an activist since college and these questions in politics and in storytelling have been crucial to me. That’s why I keep drawing attention to who has access to the ability to tell stories and who has access to power in a given society.

I look at the conditions of emergence of stories and that’s important because you don’t often see who has the capacity to even tell their stories in the first place. That sensitivity grows from what we started talking about on the origins of this book: growing up as a Vietnamese refugee in the United States, I was very aware of who had the ability to tell stories. Certainly Vietnamese refugees didn’t get to tell their stories in the American context.

And in the context of the Vietnamese refugee community, people like me—Americanized Vietnamese raised in the United States—our stories weren’t getting heard by the older generation who weren’t interested in listening to us.

I’ve always had an emphasis on who can tell a story and who can’t, and who’s going to listen and who won’t, and why the storyteller must also be aware of possibly being implicated in suppressing or ignoring other stories that are out there.

Robin Lindley: You have visited Vietnam several times and explored the cruel history of the war. Do you feel a kinship with the people of Vietnam as a Vietnamese refugee raised in the United States?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: In Vietnam, I felt I was both Vietnamese and not Vietnamese. I felt I was Vietnamese inside, and when I return to Vietnam, people certainly treat me as Vietnamese. But I’ve also been treated as an American or at least a foreigner with Vietnamese origins. The context is so important in terms of how they treat me. That’s why I’m not really comfortable in Vietnam. That’s partly because I’m not a Vietnamese Studies person. Vietnam is not my specialization.

I have friends and acquaintances who have gone back to Vietnam to establish careers there so they are greatly committed to the country and to living there. I spent a year there looking at difficult parts of Vietnamese history and culture and I’m still in a position of being outside Vietnamese culture at the same time and there are benefits and drawbacks to that and ambivalences that I put to use in Nothing Ever Dies.

Robin Lindley: What was your sense of the Vietnamese memory of the war that you found when you visited all of those places of remembrance: the cemeteries, memorials, battlegrounds?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: It confirmed that these Vietnamese memories of the war are important. They’re important to the people of Vietnam and to tourists who go to Vietnam. They’re important because they keep alive a version of the story isn’t heard globally.

It also confirmed to me that their memories are particular and exclusive just as American memories are particular and exclusive in the concern about what Americans underwent. The memories that are visible in Vietnam are expressed in a particular Vietnamese point of view. But the memories there are not even inclusive of all Vietnamese people—certainly not inclusive of foreigners such as Americans, but also exclusive of South Vietnamese and Vietnamese refugees who remember this war. Being aware of that, I can’t wholly endorse what the Vietnamese put forth as memory, even though I see it as important.

I think a lot of Americans feel sympathetic to the revolutionary Vietnamese cause and are critical of America going to Vietnam and embrace the victorious Vietnamese version of memory. But I can’t do that because I can see how those memories are also deeply ideological and limited as well.

Robin Lindley: From what you wrote, it seems that, rather than a socialist utopia, Vietnam now has a caste system and problems with inequality like we do.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yes. I don’t know exact statistics but I think Vietnam is a society with vast social and economic inequality that rivals or is greater than the United States. Perhaps the greatest irony of this war is that you have a Communist Party that fought for independence and equality and arguably neither of those things exist in Vietnam. Encountering that on my trips was so important because I am trying to think through the question of whether this war was worth it.

On one level, as an idealist, I think this war needed to be fought to give Vietnam freedom. But if the outcome is this kind of inequality and hypocrisy, there’s a crucial question at work through this book. When I was in college, a question I posed to myself in looking at the history of this war and the idea of revolution was what would I do in the place of those people? Never being able to answer that question myself, the only way to look at it was through the costs and consequences of this war for the people who were committed to it.

Robin Lindley: You have a fascinating construct of the humanities as including the inhumanities. You also deal with the other—how we saw Vietnamese as the other and how the Vietnamese saw Americans as the other. We tend to dehumanize or ignore the other. What do you see as a true war story? You discuss the version set forth by American novelist and Vietnam War veteran Tim O’Brien.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’m a humanities scholar, and so much of our work in the humanities is geared nowadays toward its celebration or its defense. We justify our work in the humanities by talking about literature and art and culture, and I believe in that. But, at the same time, I believe that is a limited notion because it doesn’t get to what I think of as an uncomfortable reality, which is that much of human behavior that we witness over the history of civilization is not an aberration but an outcome of the civilization itself. So we are short-sighted if all we do to celebrate the humanities is to think that something called inhuman is outside of that.

From my perspective, looking at this war and at other wars it was human beings that produced these actions so any meaningful humanities project has to acknowledge that the inhumane exists and that inhumane actions and their consequences have to be subjects of the humanities as well. That’s why I call on the humanities to include the humanity and inhumanity simultaneously because both are innate within us.

That’s what I think a true war story should deal with. Obviously, Tim O’Brien has a definition for what this entails. My definition is somewhat different than his because I want to talk specifically about the simultaneity of the human and the inhuman and how that is denied in focusing only on the soldier.

O’Brien’s version of the true war story, which is a great version, focuses on the soldier and what happens to him. I think that’s a very dominant way of thinking of a war in the United States and in most other societies as well. But if we think of war as both an event and an endeavor simultaneously we’re bound to understand that it’s [about more than] the soldier fighting. By focusing on the soldier we’re denying how war is only made possible with the complicity of civilians, and that society itself produces soldiers and produces wars and it’s about the individual and the society as well.

I spend a lot of time in the book talking about not only soldiers but about the boring stuff. What civilians do. How technologies work. How fantasies work. How movies and videos contribute to a true war story.

The most difficult thing for the general public to wrap its head around is its complicity in the war machinery. They think of war as carried out by soldiers and do not think about how they themselves are a part of that machinery.

Robin Lindley: You discuss American books and films about the Vietnam War in discussing memory. You seem especially moved and disturbed by the movie Apocalypse Now. How old were you when you first saw it and what were your impressions?

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think I was about ten years old. We had a VCR when it first came out and we didn’t have that many movies then, in the 1980s. So after watching Star Wars a dozen times, I watched Apocalypse Now. It was very intense and traumatic to watch and I didn’t understand much of what was going on in that movie but I did understand that it had something to do with me and with the United States. The horrific actions that I saw were carried out against people who were like me. It left a scar on me that troubled me for a very long time.

I use that film as a symbol of how American representation works when it comes to the war. There are many other books and films that do this same work, but I use this film because so many people know it.

Now I have more distance from the film and I teach it in class. I admire it technically as a powerful and significant work of art but I’m still very critical of it because it comes to stand in for American subjectivity and how it works when it comes to remembering the war. It shows Americans who think of the war as a bad war but also makes it just about themselves at the same time. That’s the kind of trick of memory that is ironically crucial to how Americans conduct themselves in foreign policy. They acknowledge the bad things that result from American foreign policy but still make the policy something about Americans and not about other people.

Robin Lindley: You express that idea powerfully. You also mention that you read Larry Heinemann’s novel Close Quarters when you were very young. He graphically details atrocities committed by American troops in Vietnam.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: That was a powerful book for me. I read it when I was 12 or 13, much too young an age for a book like that. Its depiction of things American troops were doing to Vietnamese civilians, murder and rape and so on, deeply affected me and scarred me. I’ve never forgotten it. I really hated that book and I hated Heinemann for what I thought was a negative depiction of Vietnamese people.

I made a special point of re-reading that book before I wrote The Sympathizerbecause I wanted to see if my adult feelings about that book were the same as my adolescent feelings. I found that they weren’t. I was still horrified by what was shown but I understood what Heinemann was doing as a novelist. He was saying if we really want to understand what Americans did in the Vietnam War, we have to show it, and we have to show it graphically and without sentiment or apology or excuses. When writers do that, they are not offering comfort to their readers. That leaves readers in an uncomfortable place. As an adolescent, I couldn’t deal with that. As an adult, I think he made the right decision. I learned a lot from reading his book and I thought he was right.

I’m also concerned about terrible things done by people who aren’t uniquely terrible people. I want to make the reader confront that. In order to do that, I can’t give the reader a way out. So I think Close Quarters is a novel that holds up well. It is a true war story and it continues to deserve a wide audience.

Robin Lindley: You begin your book with Dr. Martin Luther King’s sermon about the Vietnam War at the Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967. He had turned his attention from civil rights to war, poverty, militarism and materialism. He mentioned that all suffering is connected—a point you make in your book. He also said that if the United States is poisoned, part of the autopsy must read Vietnam.

Professor Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think that was a very powerful speech. I’ve read it many times and teach it in my Vietnam War class to study the war and his analysis of American society but also to understand what it means to memory in the United States.

I asked how many of my students had heard of the “I Have a Dream” speech, and everybody had, but I asked how many had heard this speech on Vietnam, and almost no one had. It got me to think about why this is the case. It’s an incredibly insightful and important speech and it’s not taught to them in high school. It gets them to understand that American society itself can be propagandistic and ideological and can encourage a memory of American character in a way that is flattering to Americans themselves. And this speech is not a flattering depiction of the American soul or psyche.

I take inspiration from his courage and how that speech cost him many friends. I take inspiration from his rhetoric and his style as well. So all of the elements of that speech were important to me and that’s why I wanted to start my book with those insights and the words and the style as well.

Robin Lindley: Thank you Professor Nguyen for sharing your insights on memory and how stories about the past are told and who tells the stories. And congratulations on your thoughtful and illuminating book Nothing Ever Dies.