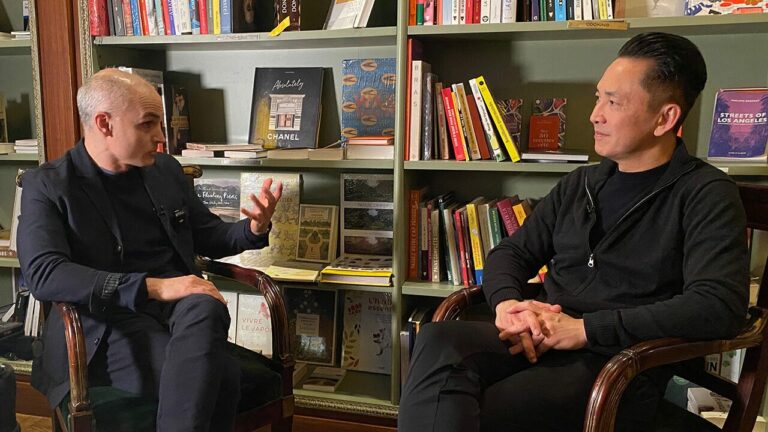

Viet Thanh Nguyen talks about The Refugees and his books with Barbara DeMarco-Barrett in this interview for KUCI.

Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, is my guest for the entire hour. He talks about his new book of short stories, The Refugees, and his nonfiction book–the bookend to The Sympathizer—Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War.

Read the transcript below:

Barbara D: Hello, and welcome to Writers on Writing on KUCI 88.9 FM. We’re broadcasting from the University of California Irvine campus. We’re on the web at kuci.org, and we’re on iTunes at College Radio. Today is Wednesday, January 18th, 2017. I’m Barbara DeMarco-Barrett, and my guest today for the entire hour is Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Viet’s novel The Sympathizer is a New York Times bestseller and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. It’s won many other honors, including the Edgar Award for Best First Novel from the Mystery Writers of America. He’s critic at large for the LA Times and has written for the New York Times, Time, the Guardian, the Atlantic, and other venues.

He’s here today to primarily talk about two of his books, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, which is the critical bookend to a creative project whose fictional bookend is The Sympathizer. He’s also here to talk about his short story collection, The Refugees, forthcoming in a couple of weeks from Grove Press.

Barbara D: Hi, Viet.

Viet Thanh N: Hi, Barbara.

Barbara D: Great to have you. Great you have you with us. Before we go on to your new books, we have to say a few words about The Sympathizer, of course. I guess mostly, I’m wondering if you were surprised with its success.

Viet Thanh N: Well, yes. Obviously, it was a very pleasant surprise, but I don’t think anyone can anticipate that a novel will do as well as that, so I’m obviously quite happy about it.

Barbara D: What were your expectations when you were writing it? I imagine it’s a big book, and I imagine it took a long time.

Viet Thanh N: Actually, it didn’t take very long to write. It took a couple of years to write, compared to The Refugees, which took 17 years to write and three more years to see publication. I think my expectations in writing The Sympathizer were pretty low because, in writing The Refugees, I was aiming for a larger audience. Ironically, in The Sympathizer, I was writing just for myself. I thought, “I hope I can find a very small, niche audience who will respond to this book as deeply as I felt while I was writing it.”

Barbara D:Now, Nothing Ever Dies came out a little while after The Sympathizer. I imagine it had been brewing for quite a while. It’s a wonderful book. It has me still thinking about some of the things I read that I want to talk to you about in a minute. Were you writing it concurrently with The Sympathizer? How did that go?

Viet Thanh N: Well, Nothing Ever Dies took me about 10 years to research. I was several articles from that book while I was doing that. At the same time, I was writing the short stories for The Refugees. Then I took a break for two years, from 2011 to 2013, to write The Sympathizer. After I was finished with that, we had 15 months before we were going to publish the novel The Sympathizer.

During that time period, I went back to Nothing Ever Dies, and I wrote the entire book from scratch during that 15-month period. The book that both preceded and came after The Sympathizer … All the research I did for Nothing Ever Dies deeply informs The Sympathizer. Everything that I learned about writing from The Sympathizer, I brought back into the actual writing of Nothing Ever Dies.

Barbara D: Okay. Take us into the process a little bit more of writing Nothing Ever Dies. When did you know you had a book, as opposed to, say, a collection of essays or long-form articles?

Viet Thanh N: Well, like I said, it took a decade to do the research for the book. I wrote these various academic articles along the way to process ideas and push me towards whatever the book was going to be. But during that entire decade, I had no idea what the actual book was going to be like. As an academic, the easiest route would have been to collect the articles and put an introduction and a conclusion on it and call it a book.

But I was increasingly thinking of myself also as a writer, and that option just looked less and less attractive to me. I really wanted to write a book that would tell a story and that could possibly shift the conversation for the general public about how it is that we think about the Vietnam War and how we think about war and memory in general. I knew that in order to do that, I really had to step back and think of the book as a whole. I just didn’t know how to do that until after I finished writing The Sympathizer. Then I realized I had the ability to then write this book as a story which could possibly appeal to someone else besides just an academic audience.

Barbara D: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Of particular interest to me … Well, there’s quite a bit, but I can’t talk about everything because we also want to talk about The Refugees. Of particular interest was the chapter on victims and voices. I think it’s in that one that you talk about the deep literary tradition of Southeast Asia. I am curious why that part of the world.

Viet Thanh N: Well, as a child growing up in San Jose, California, I was curious about my history, my past, what had brought me to the United States. I was always thinking about what kind of books I should be reading that would inform me more about that history.

My limitation was that I could only read in English. Through my teen years and then in college, I read everything I could find in English about Vietnam and about the Vietnam War. Part of the limitation of that was obviously that very little of this material was written about the Vietnamese point of view. The best that I could find were translated books from Vietnamese fiction and poetry, for example.

But then starting in the 1990s and into the 2000s, more and more Vietnamese-Americans started to tell our own stories in English. These books made an important intervention for me because in reading those books, first I could see that people were talking about Vietnamese-American experiences, but it also got me off the hook in the sense that I felt, when it came to writing The Sympathizer, I no longer needed to tell the Vietnamese-American experience.

Barbara D: Interesting. Then in the chapter on powerful memory, you talk about Michael Ondaatje’s novel The English Patient. Kip, who is actually perhaps … Well, is he my favorite character in that book? I don’t know. I love Kip. He’s Indian, and he has a realization about racism in the West and regarding Western technology and how it’s used against non-Western people. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Viet Thanh N: Kip is also my favorite character in that book. It’s a novel that is very beautiful and can be interpreted as a romantic love story and about the failures of European idealism and so on.

But the Kip character introduces a completely different dimension into the novel, which is the history of European colonization, in this case the British colonization of India. Kip’s role is as colonial soldier who’s brought from India to fight for the English in World War II. He’s a colonized subject, and his job, his task, is to defuse explosives and bombs, a very dangerous job.

Then one day towards the end of the war, he hears about the bombing of Hiroshima. He realizes that this nuclear bomb would never have been dropped on a white country. That flash of the bomb is also the moment of his decolonization, his realization that he’s working for a colonial army and a colonial government that would very easily have dropped the bomb on India if it needed to. I think he plays a crucial role in the novel because he prevents us from completely romanticizing Europe and the love story of the two other characters in the book.

Barbara D: Will you read a little bit from Nothing Ever Dies?

Viet Thanh N: Only the opening paragraph of Nothing Ever Dies.

Barbara D: Okay.

Viet Thanh N: I was born in Vietnam but made in America. I count myself among those Vietnamese dismayed by America’s deeds but tempted to believe in its words. I also count myself among those Americans who often do not know what to make of Vietnam and want to know what to make of it. Americans, as well as many people the world over, tend to mistake Vietnam with the war named in its honor, or dishonor as the case may be. This confusion has no doubt led to some of my own uncertainty about what it means to be a man with two countries, as well as the inheritor of two revolutions.

Barbara D: Thank you very much. That was Viet Thanh Nguyen reading from Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, published by Harvard University Press. What do you hope readers take away from this book?

Viet Thanh N: Well, I hope that they take away a different understanding of the Vietnam War. I think the American perspective on the Vietnam War has come to dominate global memory through the power of American culture because of Hollywood films and the power of American discourse because of global American power. The irony of the Vietnam War is that even though the North Vietnamese, or the Vietnamese communists, won the war, that perspective has been completely overshadowed.

The book is not really an attempt to say, “Let’s remember this war from the Vietnamese communist point of view.” The book is arguing that there are many different ways to remember this war besides the American perspective. Let’s talk about the American perspective or perspectives, but let’s also talk about the Vietnamese of all sides, the Laotians, the Cambodians, who were very deeply affected by this war.

Lastly, again, the book is a meditation on why we remember, why we forget, what are the possibilities of reconciliation and forgetting after a very difficult, traumatic history that two or more sides may share.

Barbara D: Well, you came to the US as a refugee in 1975 and, after settling in a refugee camp, moved to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where you lived until 1978. I’m from that part of Pennsylvania. It was hard enough for me, an Italian-American. What was it like for you?

Viet Thanh N: Actually, I think it was actually not too bad for me because, at that age, I was four to seven years old. I was a child, so I wasn’t really aware for the most part of the difficulties that my parents were going through to establish a life for us. They were not just immigrants. They were refugees. They had lost a lot of things, materially and emotionally and certainly their country and their identities. I think for them it was a hard, hard time. That was one of the reasons why they eventually left Pennsylvania to go to San Jose, California, where it would be a more hospitable environment.

Viet Thanh N: But as a child, for the most part, I had a very pleasant time just being a child. My parents were able to create that space for me. But in returning as an adult some 25 years later and seeing what Harrisburg looked like through adult eyes and the neighborhoods that I lived in, which were lower middle class and very poor neighborhoods, I realized that I was very fortunate not to have grown up there.

Barbara D: Okay. As you said, your family moved to San Jose. They opened one of the first Vietnamese grocery stores, which you wrote about in your story War Years that’s in the collection. I have to say, War Years has to be one of my favorite stories of all time. It knocked me out. I don’t know. I guess the climax of the story was so emotional. Can you talk a little bit about writing that story and bring us into that?

Viet Thanh N: War Years is the only autobiographical piece of fiction I’ve ever written, and it’s about a family in San Jose where the parents run a Vietnamese grocery store on Santa Clara Street, which is the main downtown street. That is exactly what happened to my parents. I’ve changed some of the details and exaggerated the characters, but many of the incidents in that story really happened to my family.

The crux of the story is that they’re trying to make a living, and one day this woman named Mrs. Hoa comes into their store. She’s an anticommunist organizer. She basically blackmails, or tries to blackmail, the store owners into giving her money to fight the communist side. From the perspective of the store owners, especially the mother of the narrator, this is completely unacceptable because it’s a tremendous struggle to make any kind of money. Even though they also are anticommunists, they believe that the war is over. So underneath the story of the refugees trying to make a living, there’s another story about when a war is finally finished.

Growing up in that community in San Jose, I was deeply aware of the fact that even though the war was technically over in 1975, for almost all of the Vietnamese refugees who had come over as adults, the war wasn’t done. They were still emotionally affected by that war, and they carried the legacy, the trauma of that war, with them into their everyday lives and interactions with each other.

Barbara D: That story has so many visceral details and so many specific telling details. I didn’t realize it was really the only autobiographical story you’ve written. How did you remember all of that, down to Mrs. Hoa’s roots, her gray roots coming in, or her room in the house with the uniforms and how they looked?

Viet Thanh N: Well, interestingly, all those details I made up because Mrs. Hoa was a character I never met personally, but the details of the store, the market where the family’s making a living, with rice stacked in 50-pound sacks and flypaper strips with dead flies encrusted on them hanging from the ceiling and the various kinds of fruits and vegetables and all of that and the odor that they produced, that was the store that we lived in. I recreate other scenes of life, such as the house that we lived in two doors down from the freeway entrance on South 10th Street.

But in the case of Mrs. Hoa, what happened there was I think I heard my mother tell me once, “Yeah, there are these people who are asking for money for this anticommunist case.” I certainly saw that happening in Vietnamese community events, like the Tet Festival.

But the details of her life, like what she looked like, and this very crowded house that she lives in with eight or nine other people, and the garage has been converted into a tailoring shop, I saw those kinds of things in San Jose, where people would convert their homes into businesses. I knew that multiple families were living in these places trying to make a living. It wasn’t too hard to try to imagine how confined those [inaudible 00:15:31] houses must be and how desperate the working conditions must be for the people who lived in those homes.

Barbara D: At what point in writing The Refugees or putting these stories together, what point did this story come about?

Viet Thanh N: The story was challenging to write because I don’t like writing about myself autobiographically. All of the short stories I’ve written and The Sympathizer, I’ve done my best to try to create characters that are rather distant from me personally.

The process of writing the story was challenging because I had to adopt a first-person narrator that was quite intimate with me. While I was doing that, I also had to try to get enough distance in order to write a story that made sense. It couldn’t simply be a catalog of everything that happened in my family. I had to pick and choose the details and arrange them in a certain way so that the narrative would be shapely for the reader and that the climax would make sense.

While many of the things in that story actually happened, it was the introduction of Mrs. Hoa, which I made up, through that I was able to give the story shape. Even the final confrontation between the mother and Mrs. Hoa, the revelation of the white roots that we see in her scalp, those were things that it took quite a while for me to try to figure out and insert into the story to give it a proper narrative.

Barbara D: It sounds like you revise and revise and revise.

Viet Thanh N: Writing short stories is extremely difficult, at least for me. Anybody who reads The Refugees can probably read that book in a few hours, in a day at the most, but it took me 17 years, 1997 to 2014 and three more years to see it published. The stories typically took at least 10 to 20 drafts to write because they did require a lot of polishing, a lot of reshaping, a lot of cutting.

The challenge for me in writing short stories, unlike in writing a novel, is that I have a lot to say, but in a short story, you have to say less. You have to say more with less. That was not a natural inclination for me. The story that really typifies that is the opening story, Black-Eyed Women, which I started in 1997. I finished in 2014. That story took somewhere around 50 or more drafts to accomplish. It was really, really a difficult experience.

Barbara D: Yeah. Well, I’m glad to hear you’re a reviser, very glad.

Viet Thanh N: Well, I think all writers are revisers.

Barbara D: Well, you know, although some writers really want it to happen fast and want to send their work out fast and get published fast, and sometimes too fast.

Viet Thanh N: Well, that was something I had to learn. Certainly when you’re young, or when I was young, I had ambitions that I could sit down and write, and then I’d be famous. That’s naïve. It’s also potentially very dangerous because if that had actually happened, if I had … I wasn’t that talented, basically. It took me a while to discover that I was not that talented. But if I was that talented, and I did simply just write very easily, and fame would have come to me quickly, it probably would have made me into a very messed-up person at a young age.

Instead, because I wasn’t that talented, I had to take decades to learn how to write. Not only was that an important thing for me as a writer in a technical sense, but it was important for me as a writer in an emotional sense, in the sense that it taught me humility in the face of writing and my own ego.

By the time Sympathizer came about, and the book got all this success and everything, I was able to handle it. It was very nice to get all these awards and recognition, but I was mature enough by that time that hopefully it didn’t change me in a fundamental way as a writer or as a human being. In that sense, it was a blessing in disguise to be a writer who had to learn the craft and who had to struggle with revision and with acquiring all the abilities necessary to write.

Barbara D: Where did you learn to write like this because it sounds like writing wasn’t your first choice? Can you talk a little bit about that? It sounds like you put in the years, but how did you learn to write like this? You have such a grasp over fiction and nonfiction. It’s kind of unusual. I think most writers excel in one or the other.

Viet Thanh N: Well, I think writing was always a first choice. That’s certainly what I wanted to do as a child, as a teenager, when I went to school in college. But what happened to me in college was that I discovered I was distracted by becoming a critic, by becoming a scholar, and being very politically active. Those things were easier to do than writing fiction. So when I graduated from college, I went to get a doctorate in English instead of going into a creative writing program.

At the same time, I hadn’t given up on creative writing. I took a few creative writing workshops and discovered I hated creative writing workshops and decided that while writing fiction was still really important to me, I wasn’t going to do it through school. I was going to learn the craft myself. That’s partially what took a long time. It took something like 20 years to learn how to be a fiction writer because I was also engaging in another profession as a scholar and as a teacher. I’d only write on the side.

There’s no secret to what happened. It was really just simply writing the stories of The Refugees over 17 years taught me how to be a writer in a very slow, tortuous way. What happened was really mysterious. I can’t really account for it. I just kept working at it long enough and was able to write these stories well enough to get them published in various venues.

But the real breakthrough was when my agent told me, “Your short story collection is good, but if you want to be published in New York, you have to write a novel.” I said, “Fine,” so I sat down to write The Sympathizer. Even though I’d never written a novel before, all that experience in writing the short stories had prepared me so that I felt like I was breaking through a wall and discovering my natural form in The Sympathizer, which is one of the reasons why it only took a couple of years to write that book.

I think of that moment in the Karate Kid where Ralph Macchio is being forced to do wax on and wax off, doing these pointless chores. He was really upset by that until he discovers that the whole point of that is to get him ready to be the Karate Kid. I felt that that was what had happened to me in writing the short stories.

Barbara D: Interesting. I think on that note, we’re going to take a short break, give you a moment to take a sip of water. We’ll be right back, so stay with us. We’ll be back with more Viet Thanh Nguyen in just a minute. Don’t go anywhere.

Speaker 3: (singing)

Barbara D: Welcome back to Writers on Writing on 88.9 KUCI-FM in Irvine, broadcasting from the University of California Irvine campus. We’re on the web at kuci.org and on iTunes at College Radio. This show should be joining the podcasts that are up on our site at penonfire.com. If you go to iTunes and subscribe to Writers on Writing, when it is podcast, you will receive notification of that.

We’ve been with Viet Thanh Nguyen. His books are The Sympathizer, Nothing Ever Dies, and The Refugees. He’s going to be here at UCI on January 25th and again on February 3rd. Check out the UCI website for more info, or write to me at penonfire.com. Next week, we have a speaker series event. You can also find info on that on the website. Let’s bring him back on.

Hi, Viet.

Viet Thanh N: Hi, Barbara.

Barbara D: Before we took a break, you said it took a long time to learn how to write, but you hated writing workshops. I’m wondering if you ever considered an MFA program.

Viet Thanh N: Well, I did. When I was graduating from college, I had to make a choice between whether I wanted to apply for law school, writing programs, or English doctoral programs. I just did an assessment of myself about where most my talents or abilities lay at that point. It was pretty clear that I could get into a top English doctoral program, but not a top MFA writing program. I was a model minority. I was only going to go the very best graduate programs that I could get myself into. That was this rational decision that I made.

Maybe I would have learned how to write short stories faster if I had gone through the MFA program, but I don’t have any regrets about that because I think that the other path that I chose to become a scholar and to be very deeply immersed in the scholarly tradition produced me as a very different kind of writer than almost everybody else who’s [inaudible 00:28:20] most people who have gone through an MFA program because I bring everything I know from criticism, scholarship, and theory into the writing of fiction. I think, especially in the case of The Sympathizer, that’s produced a very different kind of book.

Barbara D: Interesting. Yeah. Great answer. I want to talk more about your stories. Another one that knocked me out was The Americans. The change at the very end was … It was so masterful. I’d love to hear you talk about The Americans and how that story came about.

Viet Thanh N: In writing The Refugees, the first ambition was to write about Vietnamese people of all backgrounds. The second ambition was also to talk about them in relationship to people who are not Vietnamese.

This is what happens in the Americans. It’s a story that’s not from a Vietnamese point of view. It’s from an American gentleman’s point of view. He’s older, and he’s a veteran. He used to be a B-52 bomber pilot. He’s also black, although that’s only mentioned very briefly once, but that fact really shapes the entire story.

In The Americans, the story is that he finally returns to Vietnam, a country that he bombed, some 40 years later with his Japanese wife. They’re there to visit their daughter, who is now in Vietnam teaching English to Vietnamese children. It’s a story about confronting the past, both this pilot being finally forced to think about the implications of what might have happened during his bombing runs, and then also confronting his daughter and their very fraught and difficult emotional relationship as well.

Barbara D: What about I’d Love You to Want Me? Will you talk a bit about that story?

Viet Thanh N: I’d Love You to Want Me is about an aging Vietnamese-American couple in Orange County. They’re on the brink of a happy retirement when the husband begins to descend into dementia, into Alzheimer’s, and starts calling his wife by another woman’s name. She is unsure of whether this is simply a sign of dementia, or whether this is some secret from his past that’s emerging.

Viet Thanh N: I wrote that story because I wanted to challenge myself. I wanted to write about Alzheimer’s. I’m also very deeply interested in themes of memory and forgetting. This allowed me to talk about those themes at a very personal level for these two characters. I’m also fascinated by aging and by older people. We’re all going to end up in this situation, most of us who make it that far. It was an exercise in imagination and in empathy.

Viet Thanh N: Even though all the stories involve Vietnamese people in one way or another, most of these people are not like me. They’re older than me, or they’re from different backgrounds, or they’re different genders or sexual orientations and so on. Each of those stories also required me to exercise imagination and empathy. That’s what I try to do in all these stories, is to get away from myself and to see the world through the perspectives of people who are rather different from me despite sharing this common ethnic or national heritage.

Barbara D: Will you read from The Refugees?

Viet Thanh N: I’m going to read the first paragraph of the book, which is from the story Black-Eyed Women.

Barbara D: Okay.

Viet Thanh N: Fame would strike someone, usually the kind that healthy-minded people would not wish upon themselves, such as being kidnapped and kept prisoner for years, humiliated in a sex scandal, or surviving something typically fatal. These survivors needed someone to help write their memoirs, and their agents might eventually come across me. “At least your name’s not on anything,” my mother once said. When I mentioned that I would not mind being thanked in the acknowledgments, she said, “Let me tell you a story.” It would be the first time I heard this story, but not the last. “In our homeland,” she went on, “there was a reporter who said the government tortured the people in prison. So the government does to him exactly what he said they did to others. They send him away, and no one ever sees him again. That’s what happens to writers who put their names on things.”

Barbara D: I love that. I love that it’s a story about ghosts, and it’s a story about a ghostwriter. How did this story come about?

Viet Thanh N: Well, it was a very difficult story to write because the original premise of this story was about two lesbians. They’re in a relationship. Then one day, the ghost from the past shows up, the former lover of one of these women, who did not make it out of Vietnam, but died on the boat trip out of it.

That was a very complicated story because it involved a romantic love triangle. It involved ghosts. It involved lesbians. I could not figure out how to make it work. That’s why it took over 50 drafts because I’m a very plot-oriented writer. I wanted to make the plot function, and it wasn’t. The only way I could figure out how to solve it was to add more plot to it.

It just kept growing, growing, growing, getting more and more complicated until finally I put it aside. I wrote The Sympathizer. Then when I was finished, I came back to this story in 2014. I decided finally that I understood that less is more, so I threw out most of the story and began only with the premise of a woman who is visited by the ghost of not a lover but her brother, who hadn’t made it out of Vietnam. The other part of the triangle is their mother. Their mother believes in ghosts. The daughter, the narrator, the ghostwriter, despite her occupation, doesn’t believe in ghosts. She’s forced to confront, literally, her past in the form of this ghost.

The origins of that idea are that, for Vietnamese people, many of us, not me personally, but many of us do believe in ghosts, both scary ghosts but also benevolent ghosts, ghosts who make the final visit after their death in order to say goodbye to their loved ones. That’s the kind of ghost this story is about. It’s not a horror story. It’s actually a love story among family members involving return of a ghost.

Barbara D: I love that you let stories sit. Again, you’ve talked about this earlier, but it seems that the longer you let a piece sit, the more it comes into focus for you, the writer.

Viet Thanh N: I think inevitably, that’s true. You gain perspective on what you’ve written, what you’ve struggled with. In this story, again, I probably wrote 20 or 30 drafts in a year or two. I was simply too close to that story. I really needed to just sort of not think about it for a decade or however many years I let it lie fallow.

Again, when you’re a young writer, I don’t think, I would not have wanted to hear this. As a young writer, I could barely imagine a year or two, much less 10 years or 20 years. If someone had told me it would take me 20 years to write a short story collection, I would have probably not written that short story collection.

One of the most important skills that a writer can acquire is patience, the ability to wait and to come back, and to be able to be one’s own editor. That’s partially what distance and time allows you to do is to look at your story, not from the perspective of the writer that you are, but from the perspective of the editor that you need to be and to gain some kind of objective distance from what has taken such an emotional and aesthetic toll on you.

Barbara D: Do you have readers for your work during this time?

Viet Thanh N: My most reliable reader is my wife. Unfortunately for her, she’s read everything, and not just the final, polished version, but everything. It’s creaky drafts. If you could just see what these stories looked like when I was writing them in the 1990s, you would feel tremendous pity for her because they were awful. She’s been very, very important to me.

Then I’ve had occasional readers here and there. I had one important reader for The Sympathizer, who’s a friend of mine who’s a playwright. But for the most part, I don’t have writing groups. I don’t have writing groups that I can rely on. I don’t have a writing network that I can rely on, so I’ve learned how to be self-sufficient as a writer. That’s possibly another reason it took me so long to write these short stories.

Barbara D: How did you arrange the stories in the collection?

Viet Thanh N: There’s a narrative in the arrangement of the stories. Black-Eyed Women is about a Vietnamese-American writer and the visitation of a past upon her through this ghost. Fatherland, the last story, is about a young Vietnamese-American woman who returns to Vietnam to meet her half-sister who’s Vietnamese. The story’s told from that half-sister’s perspective.

There’s an arc in the story collection from arriving to the United States as refugees, then the struggle with being a refugee in this country and building a life here, and then finally the return to Vietnam and the perspective of the Vietnamese people in Vietnam as they look at these Vietnamese-Americans coming back.

Barbara D: Interesting. I’m curious. Because you write so well in different genres, will you talk a bit about finding the context for your ideas? Do you know, when you have an idea, if it’s a novel, a short story, an essay, a narrative for a nonfiction book? How does that happen for you?

Viet Thanh N: I think in writing the short stories, I had a hard time figuring out what idea was good for a short story, and what idea might be good for a novel. Many of the short stories in The Refugees could potentially, if I expanded them, they could become novels, for example, or short novels. At the same time, because many of those ideas could be that complicated, it was hard then to cut them down to the level of a short story.

But after I was done writing The Refugees and I was asked by my agent to write a novel, the first thing that came to mind was spy novel. I had a plot that I was really … I was able to come up with that plot fairly quickly. I think after a protracted struggle with writing, it became a lot easier for me to figure out what kind of a story might emerge from an idea. It became a lot easier for me to figure out how to work quickly with some concepts.

By now, it’s actually very easy for me to write book reviews and short essays and op-eds that are a thousand or two thousand words long. I can crank those out in a few hours. It might be the case that if I were to return to the short story form, I could write short stories more easily now, but I have no idea because I don’t ever want to write another short story again after the experience I went through with The Refugees.

It seems to me that with novels, I’m much more confident about that. I’m writing the sequel to The Sympathizer right now. It fills me great excitement and not as much dread as I would have for writing short stories partially because I have these ideas, and I think I know how to translate them into the form of a novel and its chapters and its organization. All of that comes about from having gone through the experience of writing a novel.

Barbara D: Regarding the sequel, do you outline? Do you have the plot plots already in your mind, or the major conflicts? How does that go for you in writing a novel?

Viet Thanh N: Well, in writing the short stories, I would just have an idea. Then I’d jump into writing the story and have no clue where I was going. That’s partially why it would take me so long to write each of these stories. I had to figure out all the different elements as I went along.

When it came time to write The Sympathizer, I thought, “I’m not going to do that. I’m going to have a very clear plan.” So I came up with a two-page synopsis for the novel. That synopsis was fairly accurate up until the last third of the book. But even in writing that synopsis, I knew that the conclusion that I had come up with was not really what I wanted to write, but I had to have a target that I would aim for. I hoped that, as I wrote the novel, I would understand what the ending was. That’s pretty much exactly what happened.

Having that outline was really crucial because I did map out the general arc of the plot, the major characters, where the major turns of the plot would be, the climax, and so on. That was really crucial because the novel was also supposed to function as a thriller and a spy novel, and the plot had to make sense.

In writing The Committed, I just took that concept of plotting and really exaggerated it because instead of a two-page synopsis, I have a 20-page synopsis and 50 pages of single-spaced notes. Partially the reason why I have all that information is that while I was writing Nothing Ever Dies, I was taking all these notes about what I thought might be in The Committed, whereas with The Sympathizer, I had a very skeletal plot to work from. I filled in the details as I went along. In The Committed, I have the opposite opportunity or problem, which is I probably have too much information in the 25-page synopsis. As I write the novel, I probably have to take out ideas as I go along.

Barbara D: Interesting. Well, you know, as well as being a writer, you’re an active professor. You’re all over the place speaking and taking part in conferences. Do you have a really regimented writing schedule? How do you get all this writing done?

Viet Thanh N: Well, The Sympathizer, I wrote in two years. I was very lucky. I had a fellowship. Actually, the fellowship was to write Nothing Ever Dies. I decided, “Well, I’m not going to do that. I’ll use the fellowship to write my novel instead.” Then I had sabbatical time as well.

During that time, I wrote four hours a day, and I went to the gym every day. The hour that I spent running on the treadmill at the gym was actually really crucial to the writing process because that’s where I figured out what I was going to write the next day. That was a very magical time for two years.

Maybe I’ll get that time again, but the reality of it is that what my writing schedule really looks like is what I did for most of the time that I was an academic, which was try to find an hour here, two hours there, a few days out of the week when I wasn’t writing scholarship or teaching, and do my fiction writing in the cracks of time, and then spend much more time in the summers.

That’s pretty much been the experience after The Sympathizer is that my writing schedule is four or five days out of the week, when I’m not teaching or doing administrative work, that I’ll find a couple hours a day to write a thousand words. That’s fairly frustrating because I want to spend more time, but as long as I can get those couple hours a day in, then I’m a reasonably nice human being to the people around me.

Barbara D: We have a few minutes left with Viet Thanh Nguyen. His books are The Refugees and Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War and The Sympathizer. Can you talk a little bit about how to write yourself out of something that’s not working? Have you had that experience in either writing The Sympathizer, Nothing Ever Dies, or The Refugees, where you just don’t know what to do?

Viet Thanh N: Well, in the case of The Refugees, the clear example is Black-Eyed Women. I think that I wrote myself into a corner that I couldn’t get out of after 20 or 30 drafts. I couldn’t see my way out of the complications of the plot. Again, being able to put aside the project for enough time, so that I could return to it and make some kind of an assessment of it, was really crucial.

What that means is that my way of dealing with complications in my writing is always to have multiple writing projects. I could put aside Black-Eyed Women and then turn to another short story, or I’m writing The Sympathizer, and at the same time that I’m writing The Sympathizer, I’m also thinking about Nothing Ever Dies in the back of my mind, so that when I finish The Sympathizer, I can turn immediately to Nothing Ever Dies.

That’s, for me, a really crucial part of the writing process. There’s no lag time. There’s never a time when I’m not working on a project. Even after I finish writing a book, I don’t stop and say, “I’m going to take a two-week vacation.” Instead, I turn to the next book, and because I’ve been thinking about it and taking notes, I can immediately jump into that project. I think having alternatives helps to avoid getting trapped because if you have no other alternative, you’re only writing on one project, there’s nowhere else to go if you stop writing. Then I think I would feel very guilty if I stopped writing, and that story that I couldn’t get myself around would just obsess me and haunt me. It’s nice to be able to have something else to do besides just the one writing project.

Barbara D: I’m guessing that during those times you keep social media and other time-sucks at bay.

Viet Thanh N: Well, after winning the Pulitzer, it was obviously great, but the terrible thing about it was that for eight months, I didn’t get any fiction writing done. That was because I was responding to all these requests for my time for interviews or op-eds. I was doing it to myself too. It was a very distracting time. It was really hard for me to focus on writing fiction, so I turned to writing op-eds and also to social media. I was very active for eight months, cultivating my Twitter feed and my Facebook profile and all that kind of stuff.

That is a kind of writing. It was just very distracting kind of writing, but it kept me engaged with people. It made me think that I was still doing something. There is some utility to that because I was using this platform of having won the Pulitzer to make certain kinds of political and social points to a larger audience who might not be reading my fiction. But it is quite a relief now to tone that down and to get back to writing the sequel to The Sympathizer, which I’ve been able to do over the last two weeks.

Barbara D: Can’t wait to read that. In closing, I wonder if you have any last words or any words of wisdom for the fiction writers listening.

Viet Thanh N: Patience. I think that’s a very hard thing to learn because again, when you’re younger, I think it’s hard to be patient. You’re naturally impatient. You want to move forward and get ahead. I think writing is a long game for most of us, unless you’re incredibly talented. Writing is something that you have to live with and cultivate. You have to learn how to deal with rejection and probably even worse than rejection. You have to deal with obscurity. You have to deal with people not caring about what you’re doing. You have to learn how to be patient in order to live with yourself, to watch yourself grow and to acquire wisdom. It takes age and experience.

I think that’s actually very crucial for writing. Writing is not simply a technical exercise. Learning how to do different technical things in writing is obviously crucial, but I see a lot of young writers, and they can do that. They can write stories, but they don’t have wisdom or maturity. That means that there’s a whole layer that’s missing to their writing. That’s something that you’re going to acquire through time.

Barbara D: Viet Thanh Nguyen, thank you so much for being here.

Viet Thanh N: Thanks, Barbara. It was a pleasure.

Barbara D: You’re welcome. That was Viet Thanh Nguyen. His books are The Refugees, Nothing Ever Dies, and The Sympathizer. If you haven’t read any of them yet, it’s time. It’s really time. These stories really knocked me out. As I’ve said, one of them, the War Years, is really on my list now of my favorite stories of all time.

Anyway. We’ll be back next week. If you want to know more, please visit penonfire.com. I’ll see you soon. Stay in the chair.