In the start of a new series reflecting on 75 years of the awards, Viet Thanh Nguyen writes about how societies and juries read and recognize literature for The Washington Post

The National Book Awards will celebrate its 75th anniversary at this year’s ceremony, on Nov. 20. To mark the occasion, The Washington Post has collaborated with the administrator and presenter of the awards, the National Book Foundation, to commission a series of essays by National Book Award-honored authors who will consider (and reconsider), decade by decade, the books that were recognized and those that were overlooked; the preoccupations of authors, readers and the publishing industry through time; the power and subjectivity of judges and of awards; and the lasting importance of books to our culture, from the 1950s to the present day. In this essay, Viet Thanh Nguyen — a finalist in 2016 for “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War” and longlisted in 2023 for “A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial” — looks back at the 1950s.

It’s tempting to think that literary awards go to the “best” books of a given year, and most tempting for the winners. As Saul Bellow said while accepting a National Book Award for “The Adventures of Augie March,” in 1954, “When you get a prize you feel very virtuous.” Bellow’s name still carries weight among readers, but many prize winners have been forgotten; conversely, many older books still read today never won awards in their time. Prizes sometimes predict a future member of the literary hall of fame; sometimes they’re simply given to the books that a majority of judges can agree on. Juries are not immune to the passions and prejudices of their times, so it’s no surprise that they can be both prophetic and fallible.

The worldliness of prizes, including what John O’Hara teasingly called the National Book Reward (of which he was the 1956 fiction recipient for “Ten North Frederick”), also make them an awkward fit with how many writers see their art. For Wallace Stevens, who won in 1955 for his collected poems, “awards and honors have nothing to do” with the life of a poet. “He does not accept them as a true satisfaction because there is no true satisfaction for the poet but poetry itself.” That same year, William Faulkner, who won the fiction prize for “A Fable,” said that writers are “doomed to fail,” because what they accomplish cannot match their aspirations.

From the vantage point of today, the awards from the 1950s are a mixed record, if measured by the current reputations of the 224 nominated authors (of 274 books) who were winners or finalists. Readers will know many of the names, but far from all. Let’s begin with the famous: William Carlos Williams was an eight-time finalist across categories during the ’50s, winning once for poetry; Stevens, Faulkner and Robert Penn Warren had three each; John Steinbeck, Rachel Carson and Hannah Arendt had two apiece. Most of the nominated authors scored only one appearance, including Mary McCarthy, Ezra Pound and Flannery O’Connor. Finalist recognition went to highbrow writers like E.E. Cummings (twice) and to middlebrow writers like Herman Wouk (also twice). Under which brow should a writer like Ayn Rand, a finalist in fiction for “Atlas Shrugged” in 1958, be filed? I have yet to read that novel, so I cannot say for sure.

I confess to having read only 12 of the books (although I have read poems by many of the poets) and to having heard of only 97 of the authors. Among those I had not heard of, to pick three at random: Ralph L. Rusk, nonfiction winner for “The Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson” (1950); Horace Gregory, poetry finalist for his “Selected Poems” (1952); and H.L. Davis, fiction finalist for “Winds of Morning” (1953). Then there are authors whose names I knew but whose nominated books I have not read, including: George F. Kennan, “Russia Leaves the War” (nonfiction winner, 1957); John Ciardi, “As If” (poetry finalist, 1956); and Paul Bowles, “The Spider’s House” (fiction finalist, 1956). I consider myself a fairly literary person, but these results indicate not only my ignorance but also how few of these books are still widely read, or even available to read.

Umberto Eco’s notion of one’s library as inevitably being composed mostly of books one has not read may be helpful here. “It is foolish to think that you have to read all the books you buy,” Eco wrote, and we might approach lists of literary award winners and finalists in the same spirit: They are aspirational, a log of what we could be reading and might yet read. These lists also remind us that we are probably overlooking work today that will be considered important in the future. Countercultural writers Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs are still read, but they did not merit notice from the National Book Awards in the 1950s. Neither did Isaac Asimov (“I, Robot”) or Ray Bradbury (“Fahrenheit 451”), foundational authors working in a genre that literary purists might have been prone to look down on as lowbrow and minor then, but one that is more esteemed in our time.

Science fiction was far from the only genre neglected by high-profile awards during the 1950s. Américo Paredes published “With a Pistol in His Hand,” John Okada wrote “No-No Boy,” Paule Marshall appeared with “Brown Girl, Brownstones,” Jade Snow Wong achieved success with “Fifth Chinese Daughter,” and C.Y. Lee shook up popular culture with “Flower Drum Song,” which became a Broadway musical and a landmark movie for Asian Americans. These works by writers of color helped push American literature to grapple with the complexity and heterogeneity of American experiences, but none were finalists for a National Book Award.

The equivalent of these books today might be more competitive for awards. The cultural landscape has shifted a great deal because of political and social transformations that became increasingly visible starting in the 1950s, such as the civil rights movement and the Beat Generation. Greater attention is now paid to diversity in literature, from the ranks of published authors and their editors to the composition of literary juries and the recipients of awards. While some decry this concern for diversity of various kinds, the symbolic power of book awards to address inequity was already visible in the 1950s, most notably for Jewish writers.

By my count, they made up 25 of the finalists, as compared with 42 women and only two Black writers, James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison, who won in fiction for “Invisible Man.” White men made up all the other finalists. Some Jewish American writers did not write books having to do with Jewishness, like Henry Kissinger (“Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy,” nonfiction finalist, 1958); some are now obscure, like Eli Siegel, a finalist in poetry in 1958 for “Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana”; and some notably dealt with Jewishness and became enduring names, like Bernard Malamud, winner in fiction for “The Magic Barrel” (1959) and finalist for “The Assistant” (1958). Were these writers being rewarded purely for literary merit? Or was the shadow of the Holocaust influencing the decisions of the judges, who might have become more sensitive or oppositional to the racist and antisemitic treatment of Jewish people that was more common before the 1950s in the United States?

Without access to the deliberations and thoughts of the jurists, we do not know. But the 1950s were an important decade in American Jews’ transition from being considered non-White in the early 20th century to being accepted as conditionally White. Literature played a crucial role, with Jewish writers like Bellow, Malamud and Philip Roth (fiction winner for “Goodbye, Columbus” in 1960) grappling with the ambivalent, fraught condition of Jewishness in American life. Today, when more than 90 percent of Jewish Americans identify as White and are generally seen as such, the urgency of rewarding literature by and about Jewish Americans seems to have receded, if the taste of the judges is any indication. So far as I can tell, only one or two Jewish writers have been shortlisted for an award this decade.

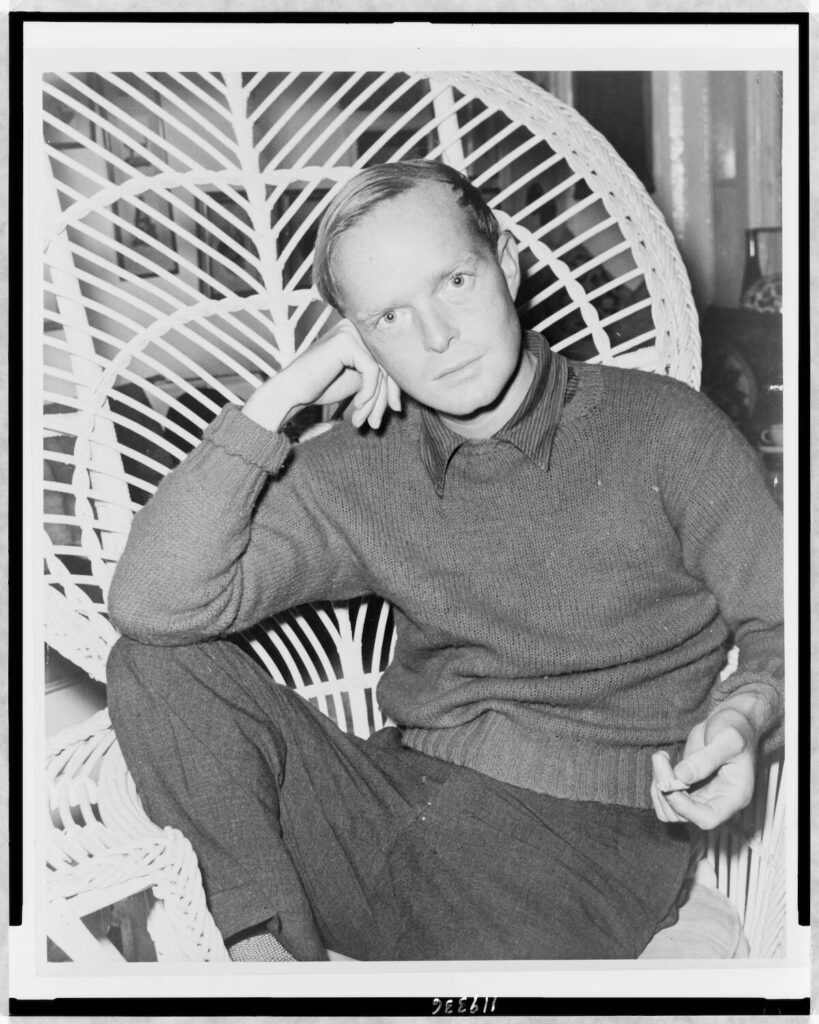

The finalists of this decade (who include non-American authors in a translated literature category, which did not exist in the 1950s) look radically different from those of seven decades earlier: By my count, there are 54 men, 42 women and three nonbinary people; about half of the authors are White, and the rest — American or international — are Black, African, Asian, Latino, Middle Eastern, Arab, Native or Pacific Islander. Several are queer, compared with only one openly gay writer in the 1950s, Truman Capote, a finalist for his novel “The Grass Harp” (1952). For some critics, this shift away from the dominant Whiteness, maleness and straightness of the 1950s indicates the troubling triumph of a suspect diversity. The ’50s, they might argue, were a time of perhaps less tolerance but greater objectivity about artistic accomplishment.

The liberal deification of minority trauma and representative “voices for the voiceless” undoubtedly exists, as Percival Everett’s “Erasure” (2001) scathingly depicts. The novel (recently adapted into the Oscar-winning “American Fiction”) includes a hilarious satire of a prestigious literary prize that looks suspiciously like the National Book Award, with an overwhelmingly White jury that votes unanimously — except for the lone Black judge — to reward a novel by a Black writer that dwells excessively on Black pain and dysfunction. But the opposite of this trauma porn scenario — the supposedly universal aesthetic standards of the ’50s — could also be seen as the genteel literary equivalent of White supremacy.

By mid-century, racial engineering through immigration law had altered the American population. In 1882, the United States excluded the Chinese from entering, and in 1924 the government shut down all Asian immigration while greatly limiting other immigrants from non-Western countries. Not until 1965 would the bans on Asian immigrants, and the low quotas on other immigrants, be fully lifted, allowing White people more than 80 years to inhibit economic, cultural and political competition from immigrants. If the Chinese immigrant population had continued its trajectory from 1880, when it accounted for 9 percent of California’s population, and if Chinese men had been allowed to bring wives from China and form families, then by the 1950s there might have been a large pool of second- and third-generation Chinese American writers to compete for awards.

This is exactly what has happened since 1965, with at least a dozen Asian American writers among the finalists in the 2020s.

Race probably affected not only who became writers but the decisions of judges. In their survey of 35 years of National Book Award decisions, Alexander Manshel and Melanie Walsh concluded that “when a majority of the judges in the room were people of color … the shortlist becomes significantly more diverse.” That majority has happened only five times in National Book Award history. And the reverse is also true: “When the jury was composed of only white judges, they selected a white winner every single time.” Ellison appears to have been the only judge of color in the 1950s, serving once. The overwhelming majority of judges were men, with perhaps one or two women in each of the years for which we have the rosters. If the gender composition of those juries foreshadowed the subsequent decades, the results were predictable: Fiction prizes have been awarded to women only 24 times.

One of the major themes of literature by writers from minoritized populations is the erasure and silencing of those who are dominated, both past and present. That theme extends to how societies and juries read and recognize literature. While some of the National Book Award winners and finalists are undoubtedly phenomenal works, the lists from which they are drawn inevitably include between their lines the potential for alternative literary histories, composed of those who might have won and those never nominated. Even these alternate lists are a palimpsest, layered over a haunting possibility: the books that might have been written by those who were suppressed before they even had the opportunity to find a voice.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Sympathizer” and the memoir “A Man of Two Faces,” among other books.