For Asian Americans, among whom I count myself, the question of Palestine holds great relevance. And for writers, among whom I also count myself, the question of when to speak our conscience has always mattered. I want to address Israel’s war on Gaza and how it raises issues of self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity that have great meaning for anyone who has been classified as an “other” and for anyone who has sought to write through that otherness. This includes Asian American, Palestinian, Israeli, and Jewish writers—all of whom have grappled with what it means to be the monstrous other. Viet Thanh Nguyen writes for The Nation

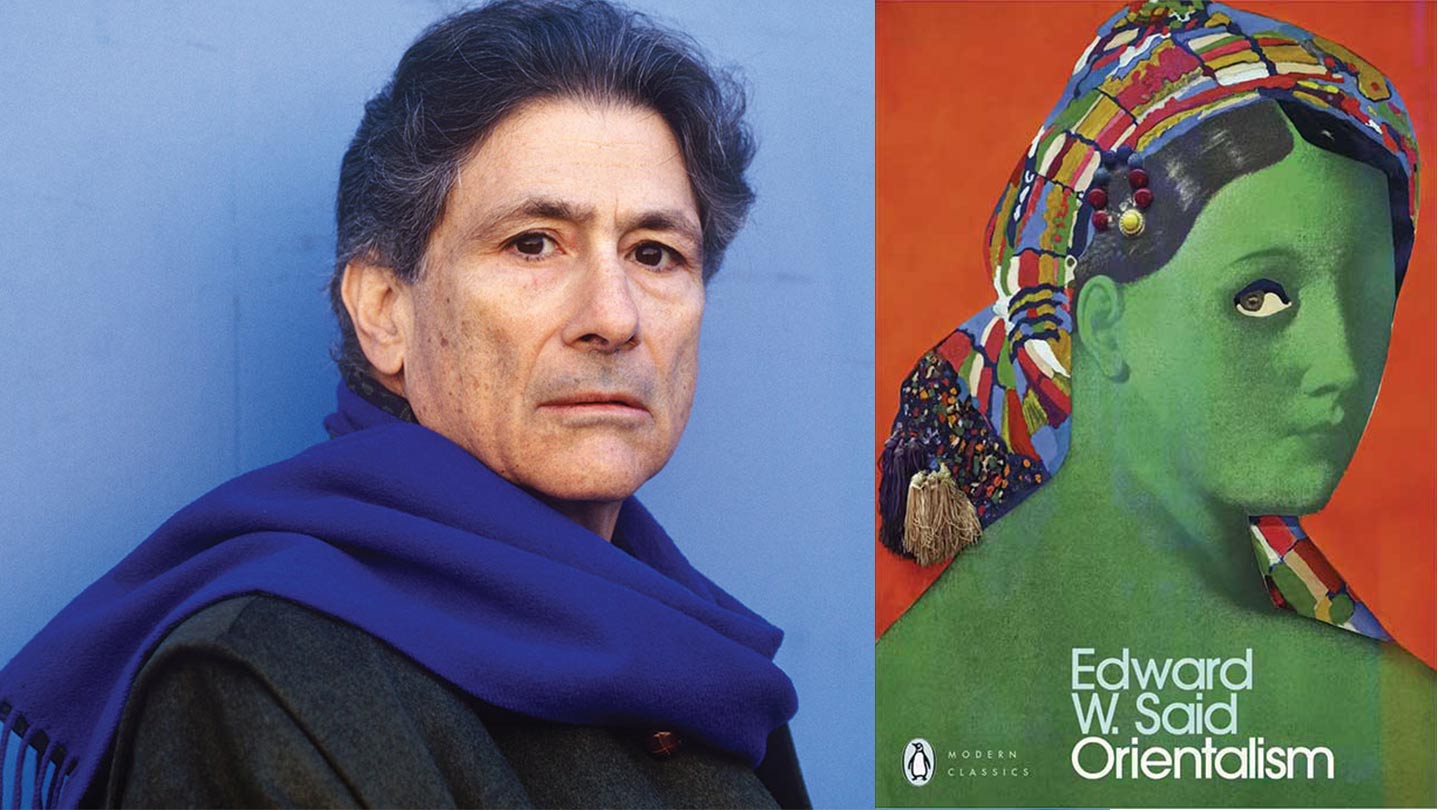

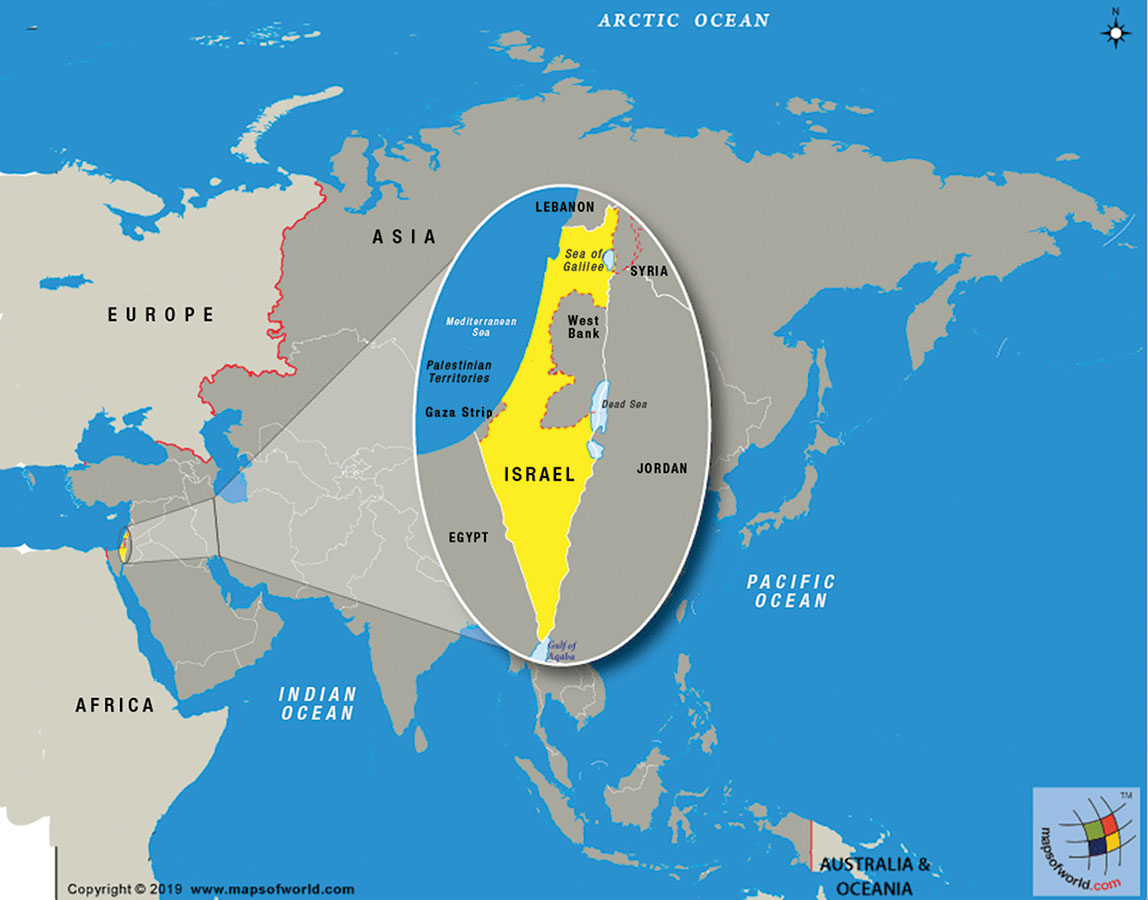

Asian Americans were once called “Orientals,” a term we rejected partly because we heeded Edward Said’s argument in his classic book Orientalism that the Oriental is an object and an opportunity manufactured by the Occident, a fantasy with very real consequences. For Asian Americans, the Oriental became a shadow to dispel, a double to destroy, a name to reject. But if Orientalism provided much of the intellectual energy that drove the growth of Asian American literature and culture, many of us forgot or overlooked that Said was Palestinian and claimed the Palestinian cause as his own. We Asian Americans appropriated his argument about Orientals, since his book did not for the most part deal with America’s Orient, found in Japan, China, Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam, which is to say, East and Southeast Asia. Said addressed Europe’s Orient, located in what Europeans called the Near East and the Middle East, and that some writers and scholars with ancestries in those areas now call, in an act of renaming and reclaiming, West and Southwest Asia.

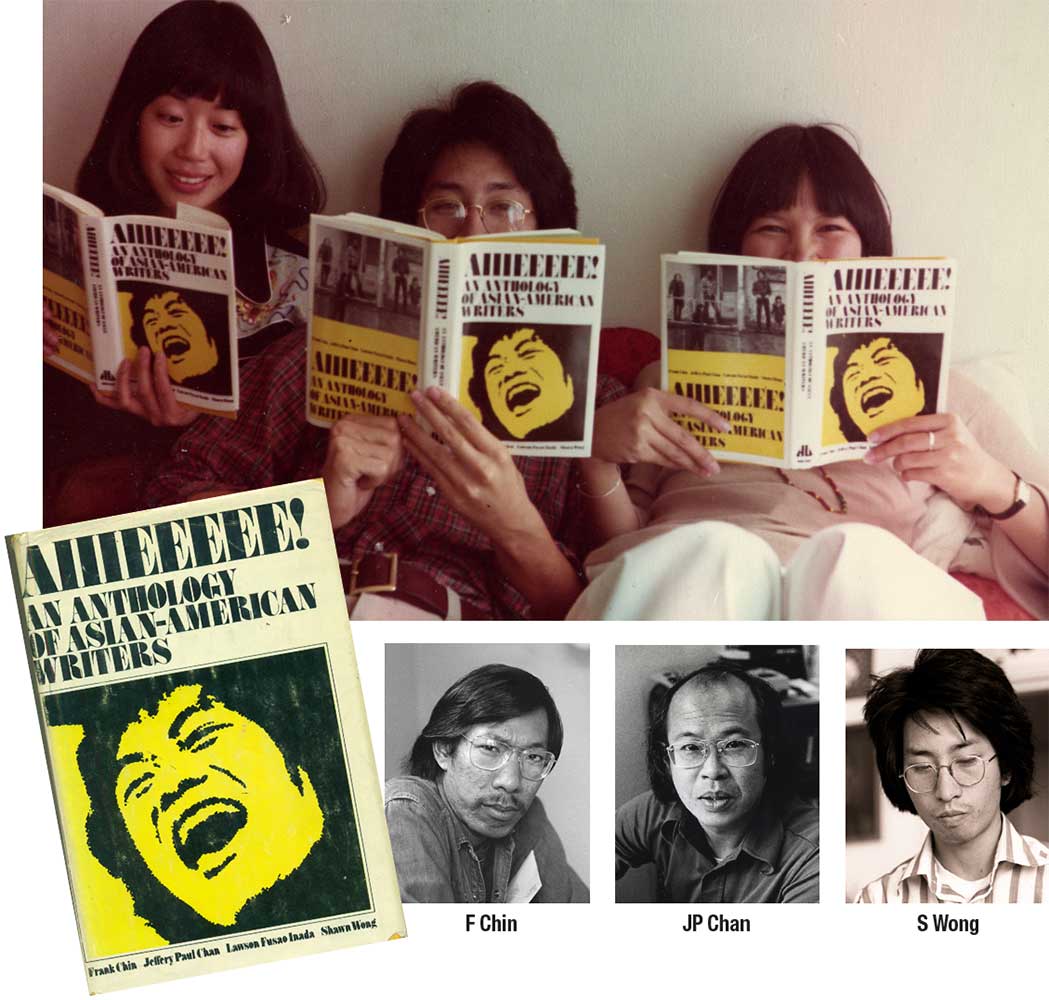

Orientalism appeared in 1978, four years after the publication of the most important anthology of Asian American literature, Aiiieeeee! The title comes from the death cries typically uttered by the Asian hordes killed by American firepower in American movies, which the anthology’s four young editors—Frank Chin, Jeffery Paul Chan, Lawson Fusao Inada, and Shawn Wong—turned into their rallying cry. The New York Times favorably reviewed Aiiieeeee! and presciently singled out for praise Chan’s short story “The Chinese in Haifa.” According to Shawn Wong, “Many reviewers could relate to Chan’s story only because it had Jewish characters in it. The story served as a cultural bridge to this brand-new thing called Asian American literature.”

Despite its impact at the time, the story has been mostly forgotten, possibly because it raised an issue many Asian Americans did not want to address or did not know how to: the significance of Israel and Palestine to Asian Americans. It is here, where Asian American literature and Jewish American representation meet over the issue of Israel and Palestine, that I will look at three key ways Asian Americans have organized ourselves, our politics, and our literature. In increasing order of difficulty, they are self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity. These three ways also resonate with other groups who have been subordinated, racialized, colonized, and so on.

Self-defense is needed to ward off efforts to kill or subjugate us, to reduce us to the bare life of a human animal. In defending ourselves, we also become the authors of our own stories. But the danger in self-defense lies in our becoming absorbed by our own victimization, and through insisting so strenuously on our humanity, becoming incapable of acknowledging our inhumanity—or the humanity of our adversaries.

Through self-defense, we seek inclusion into a larger community that has excluded us, such as the nation. But if we succeed in gaining entry, we may forget who still remains excluded as an other, and whether we, the included, now participate in and profit from the mistreatment of others.

Inclusion requires solidarity, as those who have excluded others now extend hospitality to the excluded. The excluded also need solidarity as they seek kinship with one another. But how far does solidarity extend? A limited solidarity, defining selfhood narrowly, keeping the circles of inclusion small and community identity uncontested, leads to the most acceptable politics and art in the eyes of the dominant society. An expansive solidarity, wherein kinship grows between unlikely others in an ever-widening circle, is much more dangerous, both to the dominant society and to ourselves.

These modes of self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity are all necessary, but they are also all double-edged. In the United States, these are the methods by which others have sought to become incontestably American. For Asian Americans, becoming American included a refusal to be Orientals. Finding that term demeaning, we named ourselves Asian Americans instead. Using this new name, Asian Americans wrote ourselves into being, seeking to save ourselves and the memory of our forebears from the forgetfulness of our descendants, the silences of our elders, and the violence, death, and erasure aimed at the Oriental. If the deaths of Orientals gave birth to Asian Americans, we in turn attempted to kill off the Oriental—symbolically if not literally.

The Oriental unsettles Asian Americans, but also disturbs the United States in even more profound ways in the postwar world than either the Asian American or even the Asian can, as we see in “The Chinese in Haifa.” Its protagonist is Bill Wong, who lives in the US. Wong’s wife has left him, and he is about to go fishing with his neighbor, Herb Greenberg. But on that morning, Herb is upset because his mother is about to go to Haifa, the third-largest city in Israel, and the news has announced, in Herb’s words, that “the Japs just bombed an Israeli airliner in Rome.” This incident is based on a real attackby the Japanese Red Army in 1972 on the Lod Airport near Tel Aviv, which killed 26 people, Israelis as well as some Christian pilgrims from Puerto Rico. “Goddamn Japs,” Herb says, describing the attackers as “three Japanese terrorists.” Perplexed, he asks, “What in the hell do the Japs have against us?”

To Herb, Israel’s existence is necessary for Jewish self-defense, and the Japanese attack is evidence of that need. Herb’s plaintive question implies that “Japs” and Jews should have no shared antagonism. Bill, puzzled, replies: “Japanese disguised as Arab guerrillas?” The shift from “Japs” to “Japanese” is Bill’s deliberate refusal to use such racist language. The change from Herb’s “terrorists” to Bill’s “guerrillas” is also intentional, as is Bill’s invocation of “Arab.” Herb, however, ignores these shifts as well as Bill’s confusion, which stems not just from hearing that Japanese in Rome have killed people bound for Israel, but also from Herb saying “Japs” to his Chinese American friend. Instead, Herb insists: “They were Japs, dressed like Japs.”

When I first read this story as a college student, years after it was written, I had never heard of any Japanese attacking Israelis, and I wondered why a collection of Asian American literature included a story about Chinese in Haifa. The anomalousness of the story, however, underscores the connection between Asian Americans and Jewish Americans as deviations from the American norm, two populations defending themselves against the pervasive and enduring anti-Asian racism and antisemitism that are embedded in the American grain.

Both communities also foreground the need for inclusion. Jewish Americans have sought to become a part of the United States with great effectiveness if not total success, given the endurance of antisemitism. But in 1974, not quite three decades after World War II’s end, Herb’s Americanness might have felt more fragile than his Jewishness. As for Asian Americans, we are increasingly included in the ethnic mix of the United States, but our vulnerability to symbolic and actual violence remains, as evidenced by the surge in anti-Asian sentiment during the pandemic and the need, 50 years ago, to scream in protest.

“The Chinese in Haifa” recognizes similarities between Asian Americans and Jewish Americans, situated inside and outside of the United States and Americanness. The story moves toward a tentative solidarity between them. Herb’s wife, Ethel, tells his Haifa-bound mother, “Maybe you can find Bill a nice Jewish girl, Mama, in Haifa.” Herb asks, “Are there Chinese in Haifa?” His mother says, “The Jews and the Chinese…they’re the same…. You know there are Jews in China, there must be Chinese in Haifa. It’s all the same, even in Los Angeles.”

That note of hopefulness belies the tragic unspoken histories of the Chinese and Jewish diasporas. If Herb’s unselfconscious racism mars that optimism, Bill responds in kind. He has been having an affair with Herb’s wife, and at the story’s end, Bill has his own racist daydream as he imagines Herb dropping off his mother at the airport: “A vague collection of swarthy Japanese in mufti crowding around Herb’s station wagon at the airport grew in [Bill’s] mind’s eye.” Someone normally in uniform is in mufti when they wear plain clothes, but a mufti is someone with legal expertise over Islamic religious matters. Is Bill fantasizing that Herb will be killed by pro-Islamic, antisemitic terrorists or guerrillas? Or is Bill sympathetic to Herb, who is about to be attacked by “swarthy Japanese” of the kind that once inflicted terrible atrocities against the Chinese?

The story provides no answer as to whether the attackers are terrorists or guerrillas, and gives no prescription as to whom one should feel solidarity with, or a desire to be included with, as Herb and Bill both take a stand of self-defense. The modes of self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity overlap, contradict, and potentially confuse—then and now. It is telling, for example, that Bill says “Arab” but never “Palestinian,” even though the Japanese Red Army was affiliated with Palestinian liberation efforts. His silence on Palestine foreshadows the way that Asian American consciousness will exclude Palestine, since Palestinians do not seem to be Asian. But European Orientalism was transferred to the United States when the US replaced Britain and France as the world’s foremost imperial power, and in the American imagination, Palestinians specifically, and Arabs and Muslims in general, are Oriental.

Said’s afterword in Orientalism focused on these Orientals and their representations in the late 1970s. American representations of Arabs and Muslims depicted them mostly as terrorists, with the occasional chance to be good Orientals. The good other is willing to die for the West, while the bad other is willing to be killed by the West. This dichotomy is central to how the Occident imagines its Orientals and the West its Asians. This binary between good and bad others involves both anti-Asian racism and Western colonialism. In response to this racism, people of diverse backgrounds, called both Asians and Orientals, assembled in the United States under the inherently incoherent name “Asian Americans.”

The Asian American task of self-defense is made easier if we exclude the world outside the United States and the question of colonialism. Hence, “The Chinese in Haifa” would have been much more comforting if the Japanese terrorists or Arab guerrillas were removed. The result would be a more familiar tale about America’s interethnic tensions and possibilities, about how the despised can despise each other yet learn to live together, whether as Chinese American and Jewish American neighbors or as Asian Americans who can overlook the differences between being Chinese and being Japanese. But Jeffery Paul Chan’s insistence on referring not only to Jewish Americans but also to Israelis and Arabs reveals that what happens inside America’s pluralistic society, often posed as a problem of race and racism, cannot be separated from war and colonialism.

For Asian Americans, the outside is Asia. We fear being associated with any part of Asia when that part clashes with the United States. World War II turned Japanese Americans into “Japs,” while today, the possibility of war with China has already provoked a surge of anti–Chinese American feeling that could quickly morph into anti–Asian American feeling. This fear underlies Bill Wong’s uneasiness over Herb’s use of “Japs” and the possibility of being indiscriminately painted with an Oriental brush, just as Herb might feel the same, marked by Jewishness, Israel, and the threat of violence and death.

This sense of peril also provides a unifying experience for Asian Americans—a shared history exacerbated by our concern that most of the world does not know our nation’s record of anti-Asian violence: lynchings, massacres, and brutal expulsions when white people felt there were too many of us in too close proximity. Confinement to ghettos that white people sometimes burned down. Laws preventing us from owning land, obtaining citizenship, or testifying in court, even as eyewitnesses to the murder of our friends by white people. Government decrees preventing us from immigrating to this country, making the Chinese the first illegal immigrants in American history. Signs saying “No Dogs or Filipinos Allowed.” Ruthless exploitation of bodies and labor, from Chinese workers building the railroad to Japanese and Filipinos toiling in the fields to Asian women laboring in sweatshops. The perpetual perception of Asian Americans as foreigners, the acceptability of anti-Asian jokes and slurs, the routine murder and rape of Asians in American movies and on television, all preparing the ground for the actual killing of Asian Americans. Not least of all, America’s wars in Asia, which killed millions of Asians, from the Philippine-American War of 1899 to the post-9/11 forever war waged in Iraq (West Asia) and Afghanistan (Central Asia).

These deaths of Asians and Asian Americans, in the past and potentially in the future, ironically enable the lives of Asian Americans, bringing us together in our defiance. Creating literature is one of the most important ways we’ve sought to shake off the Oriental double, defend ourselves, and fight for inclusion. Through literature, we give voice to our rightful place as Americans. However, as American power projected itself globally over the postwar world, Asian American literature became a subset of imperial literature. Is this why many of us are now silencing ourselves on the question of Palestine, because we are part of an imperial America?

Iwas saved from being an Oriental when I encountered Asian American literature and politics in college. I was shocked to discover I knew nothing of Asian American history and its violence. Renaming myself as an Asian American, I became an activist at age 19, motivated by my tremendous conviction that Asian American literature and politics enabled us to seize control of our own stories, separating them from the racist narratives that stripped us of humanity and subjected us to the terms of bare life: exclusion, imprisonment, exploitation, death. Our literature rattled the imagination, our movements shook society, each one clearing the way for the next.

As our populations and political power grew, so did our literature from its English-language origins in the late 19th century. Imagine our surprise a few years ago when the French newspaper Le Mondewrote about the success of Asian American literature in the early 21st century and used our name: “Asiatiques-Américains.” But if some of us managed to squeeze onto the great bookshelves of the West, perhaps it is because we are not perceived—at the moment—as engaging in a hostile takeover. In France, those of Vietnamese descent are treated well, partly because of the perception that we work hard and desire inclusion, but also partly because we are not Algerian, North African, Arab, Muslim, or Black, a parallel to the situation in the United States, where Asian Americans are who we are partly because of who we are not—Indigenous or Black.

In France, as in the United States, the question of solidarity looms for those of Asian descent. By identifying with other Asians of different origins, we practice a solidarity aimed at inclusion. This solidarity was once radical, as the descendants of people who fought one another during World War II—Chinese and Japanese, for example—came together as Asian Americans. While this newfound similarity is important, if we settle for it and exclude those who still do not seem like us, it becomes limiting. The question is whether we can continually practice an expansive solidarity with others whom our country excludes, subordinates, and targets the most, both inside and outside our borders.

If Asian Americans decline expansive solidarity, we signal that we are not going to take over, that we know our place—that is, until we reach some unknown point when there are too many of us, as once upon a time there were also too many Jews in the Ivy League schools. A great comic novel in the manner of Philip Roth could be written about the plight of Asian Americans at Harvard or similar institutions and how these places embody power. The immigrant themes of aspiration, assimilation, and anxiety are present, the standard dilemmas of the ethnic nouveau riche, from an earlier generation of Jewish Americans to their ethnic successors, Asian Americans.

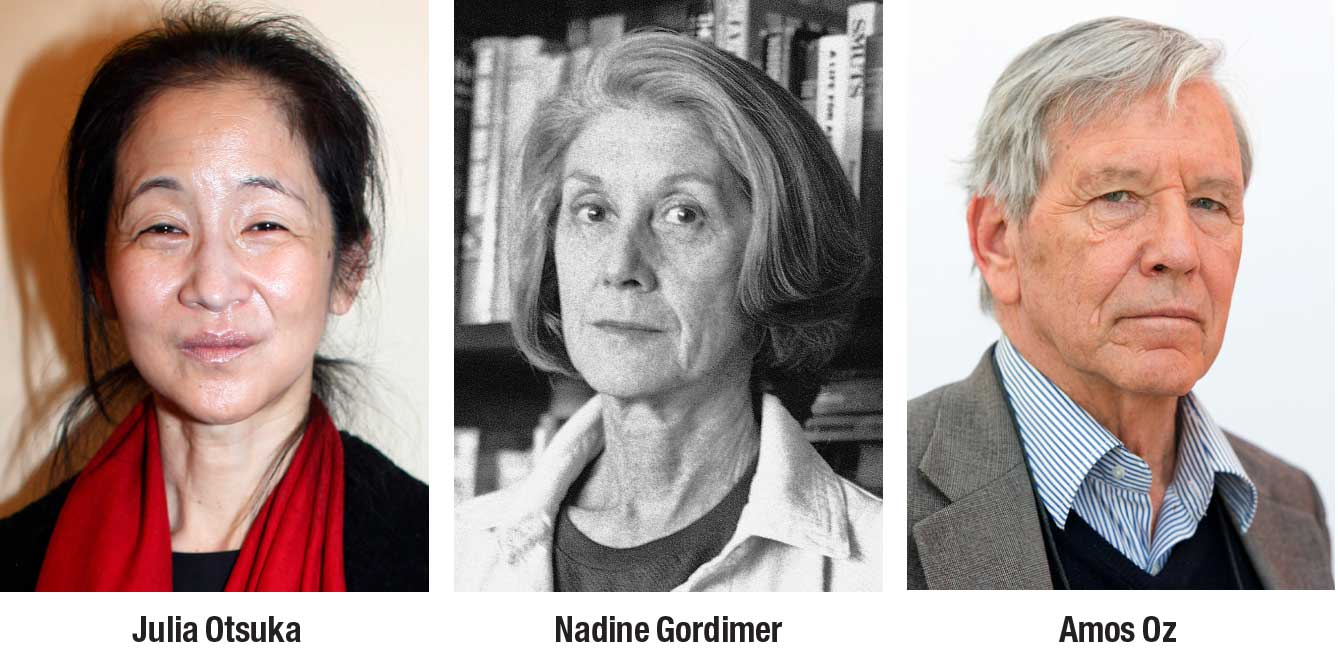

But words like “ethnic” and “immigrant” pad the hard foundations of enduring antisemitism and anti-Asian racism, as well as racialized and colonizing capitalism. To speak of capitalism without racism or colonialism exiles their embarrassing necessity in the same way that some can forget how enslavement, genocide, and exploitation enriched the West. Joseph Conrad, in Heart of Darkness, described the colonizers’ process of enrichment: “They grabbed what they could get for the sake of what was to be got…robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale….” Imperial conquest created the mass migration of fearful and hopeful Asians to the United States, where they encountered anti-Asian violence. The novelist Julie Otsuka described the danger that other Americans saw in the Japanese immigrants of the early 20th century: “We were an unbeatable, unstoppable economic machine and if our progress was not checked the entire western United States would soon become the next Asiatic outpost and colony.” How, then, to stop our progress? In the Japanese American case, through the incarceration camp, which demonstrated the arbitrariness of the law and how the state could take away rights and lives at any time.

Anti-Asian violence and Asian American death are dominant themes in Asian American literature, providing the basis for singular sorrows but also for more capacious grief, if we think about how we relate to others subjected to similar violence, how our Asian Americanness would not be possible without the land taken from Indigenous and colonized peoples. Our contradiction is exacerbated by the following problem: If the Oriental is a monstrosity, is our reviving it and renaming it the Asian American any less monstrous? Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, and Filipinos never called themselves “Asian” until they came to the United States. When these different parts could speak to each other in English, the Asian American body became animated. As that body grew, and as its capacity for speech became ever more vigorous, that body with its new name no longer seemed so ridiculous to other people and, most important, to Asian Americans themselves, as well as to those who had not yet heeded the call to become Asian American.

In the wake of the war in the former Indochina, those who sought self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity as Asian Americans include Vietnamese, Cambodian, Laotian, Hmong, Thai, Indonesian, Malaysian, and Burmese. Along with the East Asians who migrated before them, these Southeast Asians experienced European and American interventions into their countries via war and colonialism, and similar anti-Asian treatment upon reaching the US. Overseas colonialism and domestic racism have also compelled South Asian immigrants from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, and more to say that they are Asian Americans. That self-recognition—that willingness to take on a name—is the difference between being labeled Oriental or Asian against one’s will and seeking identification as an Asian American.

This identification with a group is self-defense. But the desire for identification can also lead far beyond the mere demand for inclusion, to a politics of expansive solidarity across seemingly huge differences. The incoherence of Asian America lies in the gap between the acceptable politics of limited solidarity and the potentially more radical politics of expansive solidarity. To be included, Asian Americans have to contain ourselves, daub on the makeup of assimilation to hide our seams and our monstrousness, learn what is acceptable to do and say and what is not. But to engage in a politics and a literature of expansive solidarity requires opening the self to others and saying what should not be said.

Here, the silence on Palestine in “The Chinese in Haifa” matters, and it points toward the Asian American ambivalence about how far Asia or the Orient extends, which is to say how far self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity extend—and to whom. Asia is the world’s largest continent, extending from Turkey to the west and Japan to the east, from Kazakhstan to the north and the Maldives to the south and Indonesia to the southeast. Israel and Palestine are in Southwest Asia. The geography opens a critical question: What if they, Israelis or Palestinians, identified as Asian and eventually Asian American? If the question seems absurd, that is because claiming affiliation via Asia or the Orient itself, so enormous and heterogeneous, might already seem absurd. And yet the absurdity has been outweighed by the tragedies of racism and colonialism, which have driven numerous people and their descendants from one corner of Asia to ally with people and descendants of a different corner. Are these alliances any more absurd, or less tragic, than the Jews and the Chinese of Los Angeles, of Haifa, of China, finding common ground?

Self-defense, inclusion, and solidarity are not mutually exclusive or linear stages of becoming Asian American or some other kind of other. They exist simultaneously as different, sometimes conflicting impulses. For example, we recognize Pacific Islanders and Native Hawaiians as part of our necessary coalition, even if they are not Asian American. The existence and survival of Kānaka Maoli, CHamoru, and Samoans should trouble Asian Americans, and Americans as a whole, reminding the United States itself that it is a settler colonial country violently assembled through conquest, in this case of numerous Pacific Islands and Hawaii. The more American we become, the more we may affirm this country’s settler colonialism with our silence about how we can be citizens and colonizers at the same time. The condition of our belonging, our inclusion, is our silence.

“The Chinese in Haifa” tentatively brings up colonization by mentioning “Arab guerrillas.” Guerrillas must be fighting against something, and this revolt of Arab guerrillas disrupts the anti-racist consensus that brings Asian Americans and Jewish Americans together, a unity that renders Palestinians invisible and inaudible. The ultimate silencing is death, and America’s support of Israel is inextricable from the deaths of Palestinians, the poet Mahmoud Darwish argues in Memory for Forgetfulness, his memoir set during the Israeli siege and bombardment of Beirut in 1982. Darwish says of Palestinians that “America still needs us a little. Needs us to concede the legitimacy of our killing. Needs us to commit suicide for her, in front of her, for her sake.” Describing the Israeli shelling of Beirut, Darwish could be narrating the Israeli attack on Gaza 42 years later: “I don’t want to die disfigured under the rubble. I want to be hit in the middle of the street by a shell, suddenly.”

Given the silence on Palestine in “The Chinese in Haifa,” it is fitting that Darwish brings up Haifa at the end of his memoir. Haifa, which he calls “the Dove,” is a city from which most of the Arab population was expelled by Jewish forces in 1948. Haifa symbolizes all that was lost, so much so that one Palestinian fisherman in Darwish’s telling attempts to return by rowing a boat from Beirut to Haifa. “A week later, the sea brought his body back to the coast of Tyre, back to the rock where he used to gaze at the Dove.” In another instance, Darwish asks a fellow Palestinian where he hails from. “Haifa,” the man says. But: “I wasn’t born there. I was born here, in the refugee camp.” To be from somewhere but not born there describes an exile that descends generationally, leading to an existence, Darwish says, “in a middle region between life and death.” Caught in this zone, Darwish concludes his memoir by saying, “I don’t see a dove.” Haifa is beyond reach or sight, as is everything else a dove might symbolize.

Expansive solidarity might help rescue us from the sadness and despair found in Darwish’s memoir. I end with two writers who embrace expansive solidarity as they deal with Israel and Palestine. In Nadine Gordimer’s Writing and Being, she describes being an other in her own country, apartheid-era South Africa—a feeling of alienation inseparable from the isolation of becoming a writer. Having rejected apartheid and her own implication in it, Gordimer criticized her white-ruled society, a stance complicated by being the daughter of European Jewish immigrants. Consider, Gordimer asks, how immigrants such as her parents could come to South Africa and open a store serving a community of Black miners. A generation later, the immigrants and their children have become upwardly mobile and moved on. But the Black miners remain where they are. The problem, Gordimer understood, was one of racism and settler colonization, both of which enabled her and her immigrant parents to profit, their Jewishness offset by whiteness.

Gordimer invokes Amos Oz of Israel as another writer critical of his own society. She focuses on his novel Fima, whose titular character she describes as carrying “both the embittered history, millennia of persecution, of the Jewish people, and the embittered history of their Occupation by conquest of land belonging to another people, the Palestinian Arabs.” Despite having been written 30 years ago, the words of both Gordimer and Oz are still depressingly relevant. Oz depicts Fima, an outlier among his fellow Israelis, saying, “We’re the Cossacks now, and the Arabs are the victims of the pogroms.” Fima continues: “Can a worthless man like me have sunk so low as to make a distinction between the intolerable killing of children and the not-so-intolerable killing of children?” In one charged symbolic moment, Fima comes across a cockroach in his kitchen and raises his shoe to smash it. But while examining the cockroach, “he was filled with awe at the precise, minute artistry of this creature, which no longer seemed abhorrent but wonderfully perfect; a representative of a hated race.” He leaves the cockroach alone. For Gordimer, “the hated race, persecuted and confined, is Fima’s own. He is himself the cockroach; and so are the blacks, and at [this] moment in history, in the Occupied Territories, the Palestinians. And he himself…is the hater, the persecutor, the one with the hammer, the raised shoe.”

Human and inhuman. Victim and victimizer. Expansive solidarity helps us recognize that we can be both in turn—even at the same moment. By practicing this solidarity, Gordimer could conclude her book on a quietly triumphal note: The struggle against apartheid had won, and she could finally claim her country. For her, inclusion could be achieved only by ending apartheid and settler colonialism rather than agreeing to them; otherwise, inclusion entailed an erosion of one’s soul and art. Gordimer’s expansive, radical solidarity is actually a defense of the self, her own self and the ethical, political, and artistic integrity needed to be a writer of her kind.

I return to my own otherness. Being Asian American is not the only dimension of myself. It is just one aspect, born from defending myself and others seen to be like me. But my Asian Americanness matters less than my ethics, politics, and art. Together, they constitute a repository of a stubborn otherness that resists the lure of a domesticated otherness satiated by belonging. For Asian Americans, inclusion is crucial but complicated when it means belonging to a settler and imperial country that promotes the colonization and occupation of other lands. What is the worth of defending our lives if we do not seek to protect the lives of others? As for whom we should feel solidarity with, the answer is simple albeit difficult: whoever is the cockroach. Whoever is the monster.