Host Philip Nguyen debriefs and decodes Episode 1 and then he talks to co-showrunners Don McKellar and Park Chan-wook. Don takes us through the process of adaptation and thinking about bringing this novel to the screen. Then the legendary Director Park explains some of the ways that he subverts tropes, skewers pop culture and respects an audience for HBO

Sympathizer Clip:

We will live to fight again, but, for now, we’re well and truly-

… fucked will work just fine.

Philip Nugyen:

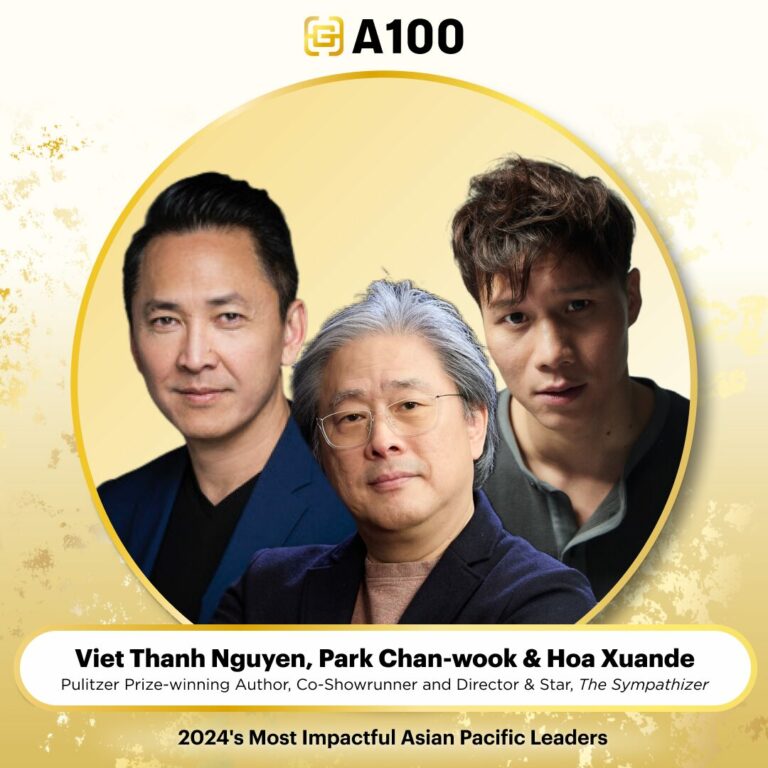

Welcome to HBO’s The Sympathizer Podcast where we are debriefing and decoding the new HBO original limited series, The Sympathizer, which is based on the Pulitzer Prize winning novel of the same name.

I’m Philip Nguyen, a scholar of Vietnamese American culture and, on this podcast, I’ll be joined by The Sympathizer’s creators, the cast and crew and, of course, author Viet Thanh Nguyen. After every episode we’ll go deeper into the characters, their motives, and how this espionage thriller/cross-cultural satire complicates what we know about the Vietnam War, aka the American War in Vietnam, and its depiction in US pop culture today. Looking at you, Hollywood.

Today we are diving into the very first episode titled, Death Wish. I’m talking with executive producers and co-showrunners, Don McKellar and director Park Chan-wook about their approaches to adapting the novel, and what to watch out for as the series progresses. Also, their feelings about durian.

But first, there will be spoilers. So if you haven’t watched episode one by now, go. Watch it right now. Stream it exclusively on Max, then come back and join us here on the podcast. We’ll be waiting for you.

Let’s recap some key moments from the first episode.

Sympathizer Clip:

[foreign language 00:01:51].

Sit straight. Now start again. Starting again is our very motto. Restart, recollect, re-educate, revolution and rewrite.

Philip Nugyen:

The series opens with the Captain in a re-education/prison camp being ordered to start over, to write another confession, which takes us to Saigon, winter of 1975.

Sympathizer Clip:

Claude asked me to meet him in front of the cinema. He was a fan of Charles Bronson. Yes, that’s right. I know that last time I’d said the movie was Emmanuel, but she was leaving. The movie was definitely Death Wish.

Philip Nugyen:

The Captain recalls his role in the capture and interrogation of one of his communist comrades, which in his undercover role inside the Secret Police, he’s forced to watch in a movie theater with American CIA operative Claude, by his side.

Sympathizer Clip:

I think you’ll appreciate this. Not at first you won’t. You’ll lock all this up in a little box, but in the future, when you look in that box again, and you will, it’ll remind you that your contribution to this war has been substantial. So keep your eyes glued to the action. Be proud yourself, at least half as proud as I am of you.

Philip Nugyen:

The Captain spends one last nostalgic night with his blood brothers Bon and Man, as the North Vietnamese Army’s artillery shells draw closer in on Saigon.

For those of you who remember your high school history classes, you may recall that this day is often referred to as the Fall of Saigon. But really what’s in a name? Especially since a war by any other name would smell as sweet, as the sweet smell of napalm in the morning. For the Vietnamese, April 30th, 1975 was either about liberation according to the Vietnamese government or loss, according to the hundreds of thousands of refugees from Vietnam and Southeast Asia who escaped political persecution, en masse, by air, land, and sea in waves to destinations unknown, in pursuit of freedom.

In our story, the general tasked the Captain with selecting who will be evacuated on the American plane that Claude has arranged for them. This operation, IRL, or in real life, was called Operation Frequent Wind, where well-connected individuals evacuated alongside their former allies.

Another campaign, Operation Baby Lift, was marked by early catastrophe as a plane crashed and exploded on the tarmac, while evacuating orphaned babies and children split from their families.

At the airport, North Vietnamese missiles fall on the tarmac. Bồn’s wife and child are killed. It’s unclear whether Bồn and the Captain make it out alive.

And we’re just in episode one.

And now I’m excited to welcome our first guest, executive producer, co-showrunner and writer, Don McKellar. Don McKellar is a Canadian award-winning actor, director, writer, and playwright, and I’m so happy to talk about The Sympathizer with hm today.

Don, as we launch into this series, how’d you get involved in this? Why The Sympathizer? Why now? Walk us through that journey.

Don McKellar:

So I was approached, Niv Fichman, one of our producers gave me the book and he’d obtained the rights. He asked me if I’d be interested. At first, I thought, I read the book and I loved it first of all. Then he mentioned Park Chan-wook, the Park Chan-wook connection because I think Viet, the author of the book, his first choice for a director was Park Chan-wook. He’s a big fan. And I’d worked with Park Chan-wook. We’d written a script together a bunch of years ago, and there’s this, the parallel with what Park Chan-wook does. The intelligence and the sort of wittiness and this sort of cruelty at times, but also this sort of expanse of compassion.

Philip Nugyen:

As a child of Vietnamese refugees myself, born in the United States, growing up with a lot of the pop culture references that are made in the series, especially thinking about the timeliness of the series, this year will be the 49th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon. And next year we’re coming onto the 50th. So I think that there are a lot of aspects of the series that speak to what is it that we’ve learned from Vietnam in an American context? And what is it that still is left to be uncovered?

Don McKellar:

Yeah, you’re right. It’s already been the 50th anniversary of American withdrawal, and so this is sort of… Right now we’re in the 50th anniversary process, rethinking of the Vietnam lesson. And I think there’s certainly this feeling that it’s time for a reassessment, time to really process what happened there.

Philip Nugyen:

It’s taken about 10 years for this project to go from the initial publishing of The Sympathizer and its winning of the Pulitzer Prize, to being adapted into a television series. Could you speak a little bit about what that adaptation process was like? Are there images from the book that you can recall that you remember being, “Oh, I absolutely want that in the show.”? Or, “I need to do it.”?

Don McKellar:

Well, the book is full of really cinematic moments, for lack of better words. So yeah, when I read it was full of stuff that was very visual. There are these big set pieces that I was excited and immediately screamed, adaptation, to me. Like the airport sequence. And each episode is a big event, kind of.

Philip Nugyen:

Almost like a benchmark.

Don McKellar:

Yeah, that’s right. They all have a big community event. This is where the community is now. They’re all sort of theatrical, extravagant moments. So yeah, it was easy to think of things that would be cool on screen. The harder thing was to think of how do we convey the complexity of the book, the intelligence of the book, the sort of wittiness of the book without having just a voiceover quoting all the great lines from the book?

Philip Nugyen:

And I think in another way, it’s also a slightly controversial book, too.

Don McKellar:

Yes. And that’s one of the great things about the book is, it’s a book of ideas. It is not afraid of ideas and even controversial, even contradictory ideas. It’s about discourse and this idea that the stories are told from many sides.

And I think the lesson of the book is that we all have two faces. That these stories all contain these internal contradictions that we can’t avoid, and that’s part of life. And you may feel you have your side, but you also have the other side inside you. Do you know what I mean?

Philip Nugyen:

Totally.

Don McKellar:

And that’s sort of liberating, but it also demands a pretty good script.

Philip Nugyen:

Right, right. Especially, I mean, you mentioned, you say the word liberating, and I think in this context, I feel me as a Vietnamese-American, having seen the series, I feel liberated by it.

I think, as I think to maybe my parents’ generation, or the elder generation, that word liberation is very charged, especially as it refers to that particular day on April 30th, 1975.

Don McKellar:

Of course, it’s a loaded day. And everyone takes their sides of whether it’s a day of infamy or a day of liberation. And obviously just a lot of people when they see we have this communist protagonist telling the story right from the beginning, are going to get their hackles up.

Like why…? Finally they tell a Vietnamese story and they have a communist protagonist?

Philip Nugyen:

Right. They’re up in arms, already.

Don McKellar:

Yeah. But for those people, I just hope, first of all, that they watch the entire series.

Philip Nugyen:

Especially since I don’t think a lot of them have read the book either.

Don McKellar:

Yeah, maybe. But Viet is fearless. He’s sort of not afraid to offend anyone. And I think we offend everyone in a way, with this series. I just feel, I hope people see that the book is about those contradictions and the character is nothing, if not flawed, the central character. And it is told by that character under duress.

So the novel protects itself in many ways by its sort of postmodern conceits. But it also acknowledges that that sort of sophistication is also the central character’s fatal flaw. Do you know what I mean? He’s almost too smart for his own good, which is quite revealing of Viet to say, because he’s so smart and so fast.

But he also, the book is saying, “But ultimately, it comes down to…” I don’t want to give away the ending.

Philip Nugyen:

Right. And I’m thinking about how even his own memoir is named a Man of Two Faces.

Don McKellar:

Exactly.

Philip Nugyen:

Right?

Don McKellar:

He’s saying, but there’s two sides. I see the other side. He’s always saying, ultimately, “I see the other side.” And that’s really the lesson of the series, I hope.

Philip Nugyen:

Right. To see both the human and the inhuman, as he says, and not to see things as just in a binary way in this either/or, but as both, and.

Don McKellar:

That’s right. Yeah, no, yeah, absolutely, right. That’s the lesson, I think. That when you ask why it’s relevant, and when we talk about the polarized world right now, it’s trying to say, “See yourself from the other side.” It’s starting to say up to Americans, “Put yourself in the Vietnamese side,” which is something that they haven’t traditionally done.

Philip Nugyen:

Really, yeah.

Don McKellar:

And then see that that’s-

Philip Nugyen:

Not too comfortable.

Don McKellar:

… and then see that that side also has two sides.

Philip Nugyen:

Right.

Don McKellar:

And that those sort of divisions go on forever, because that’s what history has left us with. We’re fractured, and then if you allow yourself that sort of leap, then it demands this kind of empathy in return, and this kind of humility. And that’s, I think, ultimately where the book lands.

Philip Nugyen:

You talked a little bit about this collaboration with director, Park Chan-wook, internationally iconic and renowned, mentioned he was one of Viet’s first choices to direct the series. I mean, what was that like? Did you ever find yourself like, “I…” Just even talking about him? Like, I’m in fanboy mode now, Don.

Don McKellar:

Well, like I say, I’d worked with him before, and so when we first met, I remember talking to him and saying, “Director Pak this, Director Pak that,” because everyone calls him Director Pak. And then he sort of laughed one day and said, “You don’t have to call me Director Pak. My name is Chan-wook, and we’re equal.”

But still, I often call him Director Pak, because it just feels right, somehow. There is something intimidating about him. I don’t deny that. He has this sort of mastery, and sort of his actions and his decisions are definitive. But at the same time, he’s very kind and open, and he actually is very open to ideas.

I always know that I’ve come up with a good idea when he comes back… If he likes my idea, he’ll say, “I like it, but it should be like this.” He always takes it one step more, which is always a great moment for me. He always pushes it farther.

Philip Nugyen:

So, our listeners, the listeners of the companion podcast, at this point in time, they would have watched episode one, an introduction to The Sympathizer series. I want to ask you this question, Director Don, about-

Don McKellar:

You don’t have to call me Director, please. We’re equals.

Philip Nugyen:

Thank you. Thank you. I’ll remember that when we talk to Director Pak. But as we start the series, what was it like to think about where you start? And how you introduce each of our characters, right, because we’re introduced to them and we are with them along their journey, right?

Don McKellar:

Yeah. Okay. So some of our earliest discussions, Director Pak and myself, were about first of all, the narrative device of the film, because as you know, the novel is told first person and this story is told in flashback. And we learn that it’s being told in a re-education camp. I can say that because we reveal that right off the top.

And the book, it’s told under duress. That was one of the things we wanted to say, right from the beginning, that because that seemed very fresh, and of course, stories told under duress, stories told by people who have had their confessions tortured out of them are not reliable, just by nature. They wouldn’t be allowed in court.

So that, right from the beginning we’re saying this, “Be wary of what this guy’s telling you. He’s telling it from one side, he’s beyond unreliable narrator. He’s the narrator who can’t tell the truth.”

Philip Nugyen:

Right. And so we’re raising all of the yellow and red flags right now.

Don McKellar:

Yeah, exactly. Right, exactly. And that was something we wanted to do right from the beginning. So we did that and then we thought, “Let’s start with the Communist spy.” The reasons why we start there will become more clear as the series continues, but we wanted to raise the question in the viewer’s mind, “Why does the Commandant want him to start with that incident? What is it about the incident in the cinema that is important for the Commandant?”

So once we decided on that, which is a moment which raises these sort of moral and ethical questions for the Captain, that sort of set the groundwork for the entire series, then that allowed us to work out, build out. And, of course, we had to end at the evacuation, at the Fall of Saigon, as the book does to us.

Sort of the most memorable think moment in the book, and also probably the moment that maybe historically, people have in their head. If they know anything about Vietnam, they probably know those images of April 30th, of the helicopters, and the evacuating people and things.

Philip Nugyen:

And this very cinematic moment.

Don McKellar:

Yeah.

Philip Nugyen:

I will say there’s a lot of prickliness that you’re working through, right?

Don McKellar:

Of course.

Philip Nugyen:

But like a durian, beneath that prickliness, it’s a beautiful custard with a not so beautiful scent, and it becomes a way to advance a narrative for the first episode-

Don McKellar:

That’s awesome.

Philip Nugyen:

… to say the least. So with my final question for you, could you share your thoughts on durians? Were those real durians on set? Which supermarket did you go to, to get them?

Don McKellar:

Yeah, people… it’s funny. Okay, so you recall viewers that the general tells the character identified in the book as the Crapulent Major not to eat durians in the interrogation process, and the durians are going to reoccur in this series. They are a kind of symbol, the prickly and foul smelling fruit, but tasty fruit.

Philip Nugyen:

Tasty.

Don McKellar:

I like them. I don’t know, do you like-

Philip Nugyen:

Of course.

Don McKellar:

Do you?

Philip Nugyen:

They’re a delicacy.

Don McKellar:

It’s not a given.

Philip Nugyen:

No, yeah.

Don McKellar:

A lot people-

Philip Nugyen:

Especially when they’re frozen, I will say.

Don McKellar:

Oh, yeah. That’s the sort of easy way to eat them, I think.

Philip Nugyen:

Right.

Don McKellar:

If you want to try it for the first time, I would say the frozen version.

Philip Nugyen:

Yes. It helps with the smell if you’re not used to it.

Don McKellar:

It contains the smell of it. And you’re right, there is a prickly element to this series. I mean, I think that it’s not a metaphor I’ve ever thought of, but I do hope that if people find those prickly aspects off-putting, or they have a smell associated with some incident in the story, maybe because of their history or their family history, that they allow themselves to taste the fruit.

When it comes to April 30th, of course, we knew it was a significant day. I mean, we had, of course, Vietnamese writers in the room, but also our cast members. Almost everyone had a story, a connection with that day. And everyone had a different take on it.

But it’s a loaded day, right? And I think, hopefully, by the end of the first series, you think whatever my associations are with that history, I’m able to be moved and feel empathy for the humanity of these people and what they endured.

Even though this guy is telling me it is, this communist who pretends not to feel that. I hope people allow themselves to step back and see the bigger picture.

Philip Nugyen:

And to give it a chance.

Don McKellar:

Yeah.

Philip Nugyen:

Thank you so much-

Don McKellar:

All right.

Philip Nugyen:

… Director Don.

Don McKellar:

Okay, thank you.

Philip Nugyen:

All right, now y’all, I have got to hold back my fanboy self a little because we’re going to be talking with executive producer, co-showrunner and writer, director Pak Chan-wook. For those who don’t know, Pak Chan-wook is a renowned South Korean screenwriter, producer and filmmaker, known for bold, colorful cinematography, black humor and dark subject matter in his films, which include Old Boy, the Handmaiden, and Decision to Leave.

In addition to his roles on The Sympathizer as executive producer and co-showrunner with Don McKellar, Pak Chan-wook directed the first three episodes of the series, and I am so thrilled to speak with him today, along with our interpreter, Jae-hoon Chung.

Director Pak, my first question for you for this first episode of the series, which we all have just watched, I want to ask you, what was it about this story that resonated with you? And could you share with our listeners how you were introduced to the novel in the first place? And were there any moments from that novel that inspired you to take the helm as a director of the series?

Pak Chan-wook:

[foreign language 00:21:09]. So one of the producers on our project is Niv Fichman, and I’ve known him for many years even before this Sympathizer. And he called me out of the blue, and he told me that there’s a original novel that we want to adapt into a TV show.

So he told me, “Can you actually read the original novel and think about it?” So I went to the bookstore and fortunately, it was already translated into Korean language. So I bought the book and I read it, and as soon as I read it, I made a decision that I would like to be involved in this project.

And also not only that, as a Korean, there are a whole lot of similarities between us and what the Vietnamese went through. Not only the Korean history, but in terms of wider spectrum, in terms of the Asian history, and also the story revolves around the East and West, the relationship and the ideology conflict between the socialist and the capitalism.

All that is to say as a Korean, it didn’t feel like this is someone else’s story. It felt like I resonated with it very much. So I made a decision right away to participate in this project.

Philip Nugyen:

I want to ask you about something that the author, Viet Thanh Nguyen had said, Director Pak, what he calls “the propaganda of pop culture”. And for you, in the director and co-show runner role, as you were adapting the series, could you share a little bit of your thoughts about how this series either is a part of that propaganda of pop culture, or speaks against it? Especially thinking about the political motivations that are in the novel and how the series, I anticipate will be very, very mainstream.

Pak Chan-wook:

Pop culture is [foreign language 00:23:17]. I would like to define that while our show is a study about the propaganda features within the American pop culture, it also went beyond that and it approached about the propaganda in a meta sense.

We also attempted to not leave a trace that was about defending one side or the other.

The story is talking about how an individual or a group that has fell into a trap of dogma or ideology, actually can fall apart from their original intention and commit such cruel act. And in doing so, how it might leave out lives of individuals.

We try to look carefully of every single one of them and portray them with care.

In terms of commenting about the propaganda, our fourth episode is actually centered around that idea. The episode portrays satirically and critically about the auteur, who is played by Robert Downey Jr., who is actually making a movie about the Vietnam War.

Which is not to say we are criticizing about such ideology, whether one is bad, or if all the ideologies are bad. That is actually why we end the series with the mind that says, “Despite everything, I hope for the revolution.”

Philip Nugyen:

I want to ask about what drew you to using flashbacks and flash forwards as a way to frame the Captain’s experience, as well as to draw parallels between life in Vietnam and life in the US? Especially as we see the ways in which he develops as a character, right? As well as in a more introspective way, the significance around using these bilingual voiceovers that we’re introduced to the series with, as a way to get into his head as he’s re-narrating or re-writing his story?

Pak Chan-wook:

[foreign language 00:25:57]. So the thing is, the framework had been originally set in this original novel because this takes place in re-education camp as the Captain writes his confession. And of course, we can go about changing this framework, but I thought this confession as a frame was actually a strong suit in this novel.

And by doing so, many times when you’re translating literature work into a visual medium, then you have to abandon what goes on in the protagonist’s head. But because we can use by embracing this confession framework, not only can I use the confession, but also I can use the Captain and his conversation with the Commandant, sort of like a Q&A. So that I was able to use that many times and I was able to use that to make a moment out of it by using those moments as a flashback gateway.

And not only that, we went about using drawing from Viet’s very excellent prose. We were able to borrow his writing and also use some of his dialogues, but also on top of that, that Don and I came up with new lines as well.

We tried hard to avoid making a voiceover that is too explanatory or too on the nose, but at the same time we were very conscious about making voiceover so it will make you laugh or make you sad, and use this voiceover and embrace it as a device in terms of the filmmaking.

So we went about using this voiceover so we can go to the past or move forward to the future in a free way. And we also went about being playful about using the transitions, not only visually but also auditorily. And we thought about how to use right timing in terms of editorial. And I strived hard to make how to go about using the flashback in multidimensional way.

By doing that, I actually embraced how it interrupts in the storytelling, and how we can go to the past or present or the future as much as we want, and anytime we want in terms of the editing of the episode. So I actually use this device as a filmmaking or TV edit device.

In other words, it wasn’t about fooling the audience, presenting the story as a real story, but I went about making it so they are already know that this is a made-up story. For example, the story progresses and the voice interrupts and the voice says, “Wait a minute, you said something else the last time,” and then the image freezes and then we rewind, and then when it picks up again, we introduce a totally new information.

That’s sort of the format we went about achieving.

[foreign language 00:29:44]. And actually the reason why the voiceover is so interesting is because the Captain uses dual language. So we have the Captain, whenever he’s thinking by himself is spoken, or he’s thinking in English. And there’s a very deep meaning behind this. Because in fact, when he’s writing the confession, the text itself is written in Vietnamese.

So when he’s writing the confession, he’s writing in Vietnamese, but when he’s thinking he’s speaking or he’s thinking in English. So I won’t go any further than that, because it might be a spoiler. But this is intentional device that we used in order to portray the duality of the Captain, his essence.

So yes, and at the same time, when we have the conversation between him and the Commandant, the questions and the conversations, those are all happening in Vietnamese. So for the viewers, really paying attention to when the English is spoken and when we switch to Vietnamese, that’s something you should keep your eyes on, to understand the meaning behind the series as well.

[foreign language 00:31:12]. So think about it. For example, for American dramas or film, there are many work where there are foreigners or non-Americans, but they speak in English. For example, we have Nazi officers speaking in English, and even though they’re speaking amongst themselves, the thing is they speak in British accent, which is so silly. And it has been accepted for so many years.

So The Sympathizer, if you look at it, the viewers will be pondering and it will give them a chance to think about a challenge this mannerism that had been happening for so many decades.

Philip Nugyen:

Dr. Pak, I am sure you get this often, but that is brilliant. It makes so much sense, especially for folks that may understand both English and Vietnamese. Thank you, Director Pak for giving us some of that insight.

I want to ask you about Robert Downey Jr. playing multiple roles. In the first episode we’re introduced to Claude, and later we’ll be introduced… I don’t want to give too much away, but to the professor, the congressman, and the auteur. Would you be able to tell us about how you came up with this idea for Robert Downey Jr. to play all of the white patriarch characters, and how that meta-textuality or symbolism comes out throughout the series?

Pak Chan-wook:

[foreign language 00:32:44]. So when I went about writing this show, all of the characters or each of the characters that Robert ended up playing, they were very important, on each on their own terms. At the same time, I obviously wanted to bring life into them, and I wanted to portray the characters extremely well. But the thing was, the running time, or I should say the screen time for each of the character was very limited.

And while I wanted a great actor to portray these characters, because they were so short in terms of the screen time, I worried that no one would be able, or no one would be willing to take the job. So I went about dissecting the differences and the common things they shared amongst the characters. And even though their jobs may be different, and even though each and every one of them might have different characters, at the same time, I learned that they were representation of America’s imperialism or American ideology.

So they were just sharing one body with many different faces. So in the essence, they were all in the same one individual. So my next question, my next step, was how to go about portraying this idea effectively and accurately to our viewers. So my thinking was it shouldn’t be that the critics watch this many, many times and figure this out. My hope was that viewers will watch it and immediately they would understand the idea that I was going for, which led to this one single individual actor playing these various characters.

But that also led me to think about setting this limit, imposing limits, so we wouldn’t be going about using too much of prosthetics or VFX, so that each of the characters will be drastically different, so that the audience would understand and right away know that they are one and in the same actor played by one individual.

And it required a great skill, great acting ability in order to portray this without going over the limit, which required a great superb craft and skill.

Philip Nugyen:

I want to ask about one thing that you mentioned in an interview with the academy about your film, Decision to Leave, which employs this sort of contemporary communication technology. You had mentioned that you wanted to use a fountain pen instead, and a fountain pen is what our Captain uses for spy craft in this series. Is that intentional? Is there some continuity there and the broader scope of your work? And before we get into the language aspect of the series too, right, the role of writing as a part of this meta-textual narrative?

Pak Chan-wook:

[foreign language 00:36:05]. So in terms of writing device writing, with the fountain pen on the paper, I feel like that is the most elegant and beautiful action. In terms of a sound and in terms of the appearance, and also in terms of the color of the ink, it’s a very great device to use to capture in film.

For a Decision to Leave, I couldn’t really afford to do that because it is set in 2020, modern era. However, in terms of The Sympathizer, yes, it was based in 1970s, so we could have afforded to do that, but we weren’t really able to freely explore it, because even though there are a whole lot of writings happening at the re-education camp, I don’t think they would allow them to write in fountain pen, because it’s quite expensive and it could be a weapon. And I thought about maybe, perhaps pencil? But, if they were to write so many pages of confessions, then that will require knife in order to sharpen the pencil, then that will become a weapon as well. So unfortunately, we had to resort to using very uninteresting ballpoint pen.

So I dare say, the show is actually about the writing, because obviously it’s about him writing the confession in terms of the format of the show.

[Foreign language 00:37:56]. And in the very first episode and within the first line, he mentions the rewrite. And I don’t think this is spoiler, but also at the end of the episode, there’s a mention of rewrite again.

So just like how we open the show and how we close the show, I think it implies the writing is very important in the show. I think writing, the acting of the writing is very meaningful in that it’s an individual reflecting about his life, his identity, his misdeeds, his sin, is something that the act who goes about reflecting upon his life, who actually goes about writing these things.

And it’s not only about whatever incident that had happened, it’s more about what had been omitted, why such incident had been omitted, or actually, how he would switch the order of the story and the format. That actually has much more meaning as well.

So it is not only about what is written in each individual sentence, but it’s also about the structure of the sentence and what is omitted in the sentence. So having said that, I think I believe The Sympathizer show, it reflects how important the act of writing is.

Philip Nugyen:

Thank you, Director Pak, as I sit here writing notes with my fountain pen to evoke that sense of what it means to listen and to commit to memory the stories that I’m hearing, right? And as a way to sort of connect to the past, I think. As you’ve demonstrated, you’re a master time traveler yourself.

Director Pak. I just want to thank you for the time, and I’m so honored, appreciate you and your work. My last question is for the first episode, were the durians on set CGI? Or did you have to deal with the smell?

Pak Chan-wook:

[foreign language 00:40:16]. So actually that was not CGI, that was props and it didn’t smell. But even if it was a real thing, I wouldn’t be disgusted by the smell, to be honest with you.

Philip Nugyen:

And I hope in that spirit, everyone listening to this podcast and watching the series, continues to watch the series and understands all of the delicious custard that lays under the prickly outside of the durian.

Thank you so much, Director Pak, for joining us on the official Sympathizer companion podcast, and congratulations.

Pak Chan-wook:

Thank you. Bye.

Philip Nugyen:

Wow, and that’s a wrap on episode one of The Sympathizer Podcast. Many thanks to showrunner Don McKellar and director Pak Chan-wook for joining us today.

We’ll see you all next time when we’ll dive into episode two with actor Hoa Xuande, who plays the Captain, executive producer from Team Downey, Amanda Burrell, and The Sympathizer author himself, Viet Thanh Nguyen.

In the meantime, stream new episodes of the HBO Original Limited series, The Sympathizer, Sundays exclusively on Max, and subscribe and listen to the podcast after every episode of the show on Max, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Don’t forget to enjoy that durian smell and taste altogether.

The Sympathizer Podcast is produced by the Mash-Up Americans for HBO.