[Lede translated by Google] One of the most significant literary events of the year was the arrival in Bucharest of the Vietnamese-American writer Viet Thanh Nguyen. The Sympathizer, his 2015 debut, won the author the Pulitzer Prize for fiction and was adapted into an HBO miniseries. Viet Thanh Nguyen writes about immigration, politics, war, and society, and is recognized as one of the most valuable authors in recent American literature. We invite you to read an interview with the author about his literary activity, but also about the role of the writer in society and other equally relevant topics for Observator Cultural.

Dear Viet Thanh Nguyen, it was a real pleasure to have you as a guest in Bucharest! It was the first time you have visited an Eastern European country so I have to ask you what were your expectations coming here and were they met or exceeded?

Of course, I was excited to visit Romania and Eastern Europe for the first time. As someone born in Viet Nam, I felt that I might have a few things that overlapped with Romania and Eastern Europe. First, a shared history of communism. Second, Viet Nam and East and Southeast Asia have been subject to stereotyping and Orientalist assumptions by the West, and it seems to me that Romania and Eastern Europe, while obviously quite different than my part of Asia, nevertheless are east of Western Europe and subject in their own way to a certain kind of fascination and caricaturing as being exotic and other to the West. I was aware of that history and wanted to come to Bucharest with no expectations except to learn a little about the city and the country, and I certainly did, from food to architecture to recent, postwar history.

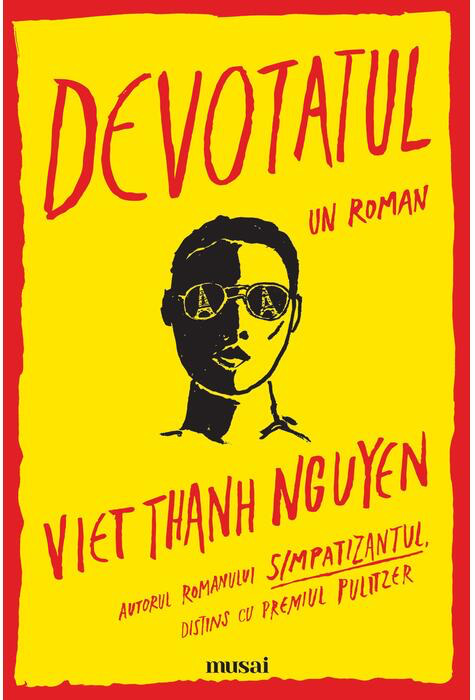

One of the main reasons why you came to Bucharest was the recent translation of your 2021 novel The Committed, the sequel to your Pulitzer Prize-winning The Sympathiser. Why did you feel that the story of your protagonist was not finished and that it required a follow up?

The Sympathiser was a novel about a communist revolutionary who becomes disabused of the communist revolution, but who isn’t ready to just become a capitalist. From a capitalist perspective, that’s the only solution to the failures of communism. But I was curious about what a revolutionary would do who still believes in revolution and who isn’t enamored of capitalism. He also thinks he’s hit bottom in The Sympathiser, but discovers that there’s even more depths to himself that he hasn’t understood. Hence, a sequel, where he struggles with ideas about revolution, and not only revolutions concerning states and capitalism, but gender and sexuality too.

The Sympathiser is about America and Vietnam, The Commited focus on France and Vietnam. You have stated that there is one more novel to come in order to complete a trilogy. What’s left to say from a cultural and political standpoint about these subjects that you need to write another novel?

If The Sympathiser was a spy novel where the action is also about the failures of the capitalist and communist revolutions, The Committed is a gangster thriller about how those revolutions are organized forms of seizing control of violence. What’s the difference between a gangster and a revolutionary, or a gangster and a statesman? The statesman has even more violence at his disposal than a gangster, because the state has a monopoly of violence, which it seized through earlier revolution. I think a third novel is needed—and it will be the last one—because one needs a synthesis after a thesis and an antithesis, which is what the first two novels represent.

In The Committed there is a French teacher who says to his Vietnamese pupils that by learning French language and literature they can become French as well. There is a rich tradition of cosmopolitan thinking that seeks to find how we can be citizen of the world. Do you think that the literature that creates a transnational frame of reference can contribute to the feeling of belonging to a global community, avoiding in this way the repetition of the tragedies of the last century?

I’m a believer in the power of literature specifically and culture in general to open us up to the world, to increase our empathy, to cultivate cosmopolitanism, and in all these ways prepare us for a world in which world citizenship is possible for the many and not just the few. However, we are still far from making such a world a reality, so I don’t want to overstate what literature and culture can do. The feeling of belonging to a global community is still a minority feeling, and it is experienced differently by writers and artists and travelers than it is by billionaires. Unfortunately, billionaires and the global corporate class have more power over the shape of our world than artists and writers. So even though artists and writers can help shape our imaginations and feelings for a more cosmopolitan world, I fear that tragedies old and new still await us as we, as a species, try to make that world actually exist.

In both of your novels, the masculinity of the protagonist is a very important theme and its deconstruction works brilliantly as a textual tool to analyse the consequences of political changes and of colonialism. Why do you think is gender a relevant filter in postcolonial research and in the analysis of contemporary society in general?

Patriarchy and heterosexuality are dominant forces in many and probably most parts of the world, and they shape the way that men rule much of the world and interact with women, and they shape how many women interact with the world as well. I don’t underestimate how much our notions of gender and sexuality, which are fundamental to our individual visions of ourselves and others, thus also infiltrate everything else, from the economy to politics to war. The rhetoric and posture and actions that we use in these realms is oftentimes implicitly and sometimes explicitly gendered and sexualized, and this is not simply metaphorical. Any attempt to change societies to deal with things like the economy, for example, but which don’t address how economic inequality and power is distributed unequally across gender and sexuality, is going to be deeply limited.

The Sympathiser is loosely based on the life of Phạm Xuân Ẩn, The Refugees is probably inspired by what have you seen growing up in Vietnamese communities. Do you ever feel remorse in borrowing elements from real people lives or do you think that this is necessary in representing these people?

I feel very little remorse, probably even none, even though I know that some Vietnamese readers don’t care for me or my work, and I am aware that the Vietnamese government won’t allow much of my work to be translated into Vietnamese. Writers have to borrow and steal from everyone we meet, and we have to speak the truth, even if we upset certain people or governments. That being said, my newest book, A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, A History, A Memorial, draws from the lives of my mother and father, and so it is very personal and this question of remorse becomes quite different. My mother has passed and my father is fading, so I will never have to confront whether they would be angry with me or not.

Speaking about representation, you have this quote on your Facebook’s bio: “Don’t be a Voice for the voiceless. Abolish the conditions of the voicelessness instead”. Do you think that the contemporary writers should tackle the major problems of their society? If yes, then I have to ask how, exclusively through their fiction or beyond that?

If writers don’t tackle the major problems of their society, what are they going to write about? Some writers will construe the major problems as economic exploitation, or imperialism, or racism, or sexism. Other writers will construe the problems as spiritual desolation, or alienation, or hypocrisy, or betrayal. Regardless, if a writer does not see their story, no matter what it’s about, as having some connection to larger challenge or problem in society, it’s hard to see how many readers will care. That being said, this doesn’t mean that the state should mandate that writers grapple with things, or that there should be a mandatory set of aesthetics. Writers have to figure out these issues on their own, which includes the question of genre, and even the distinctions between genre. A Man of Two Faces, for example, is written like prose but looks a lot like poetry in some places, and this is due to my feeling that this blend was the right formal response to how I felt my emotions, and my thinking about how the borders between genres bear some relationship to the borders between countries. I exist as the writer and person I am because the Chinese and the French and the Americans violated national borders and did whatever they wanted, and therefore as a writer I have the freedom and maybe even the obligation to transgress all kinds of generic borders as I attempt to write my response to the social and political issues that concern me.

Your writings are also one of the best analyses of the binary thinking of the Cold War that I have read. You criticise both communism and capitalism and you constantly argue that you don’t have to blindly chose for one of the two. How are you perceived in America and in Vietnam?

The literati in America seem to like me fine, given the prizes, honors, and invitations I’ve received. The conservatives and nationalists who have read me don’t like me, from what I can tell, but it doesn’t seem like most conservatives and nationalists read or at least read my work, so this hasn’t been much of a problem for me. The book banning that is happening in the United States mostly revolves around issues of blackness and queerness, and so my subjects are not as topical for the far right imagination. As for Viet Nam, what I have heard is that those who can read English—which already denotes a certain kind of class and education—like my books, partly because they offer a non-state sanctioned view on some contentious aspects of Vietnamese history. But since most of my work can’t be published in Vietnamese, my impact is limited there.

You have written extensively about war. Your novels don’t feature the actual fighting, but its consequences. Do you think that the public discourse and the representation of war is another battleground, a more subtle one? It is this the case with the Russo-Ukrainian War?

War and its representation are totally different matters. I wouldn’t even dare to guess what a soldier or civilian or refugee who has gone through war feels like. I have heard and seen an AK-47 being fired for fun very close to me and it was terrifying, even though that gun wasn’t aimed at me. I extrapolate that by a thousand and imagine the bullets aimed at me or hitting people close to me and I assume that my imagination can in no way approximate the physical and psychic pain and trauma that war and terror can sow. That being said, representation is a different matter. Everyone who lives through an experience will die one way or another, and after they die, there’s nothing left of what they’ve experienced. What we have left is representation. It’s still possible, therefore, for something like a poem or novel to tell us something meaningful about war, even if they are not written by people who’ve actually experienced war. Because, in the end, after everyone who’s lived through that experience is dead, all we have are these representations, and if they feel truthful to us, that’s what counts. I’m gratified that people who have survived the war in Viet Nam and the refugee experience have told me that they think my work does actually capture some elements of those experiences. In terms of the Russo-Ukrainian War, there are these actual experiences that matter tremendously to the people undergoing that war, but the rest of the world only sees that war through representation, which is why the war of representation actually matters a great deal. There are mutually competing propagandistic narratives out there, from Russia to Ukraine to the USA and NATO, and it would be naïve to think that any of these narratives are somehow the unfiltered truth of what’s going on.

The TV adaptation of The Sympathiser is promoted as HBO’s next big hit. There are many writers that are very sceptical towards adapting their writings. What do you think this project will add to the understanding of your novel? What were the biggest challenges in making this TV show?

The biggest challenges are artistic, because so many people are involved in making a TV show versus a novel, and cultural, because the United States has had such a deeply ethnocentric view of the war in Viet Nam, and my novel contradicts that view. So it was important to me that I trust the team which so far has built the TV show, beginning with my producer, Niv Fichman of Rhombus Media. He did movie adaptations of Jose Saramago’s Blindness and The Double, and this track record was persuasive to me. He’s also not American, an additional and important factor, as Americans are signficantly limited, on the average, in approaching their war in Viet Nam from a non-American point of view. Niv brought Park Chan-wook on board, a director I greatly admire and whose vision overlaps considerably with mine. His classic Oldboy, for example, was an inspiration for some of the aesthetics in The Sympathiser. Niv and Director Park, together, brought A24 to option the novel, and A24 has an amazing track record in TV and movies, including those dealing with Asian Americans (most recently, the Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once). I don’t know if the TV series will add understanding to my novel, but I felt it was an important opportunity to make a TV series out of the novel because a novel only has so much reach. Even a great novel might only reach tens or hundreds of thousands, while a bad TV show can still reach millions. The representation of the war in Viet Nam has been deeply influenced by American movies, and so using an American entertainment mechanism like HBO might make some impact on this kind of representation, which is also a global representation, given the dominance of American soft power.

Your memoir, A Man with Two Faces, will be published this autumn. How did you feel telling your own story after writing for so many years about communities and nations?

Terrified.

In the last years, a lot of workers from South Asia came in Romania to. So far, there are no really coherent movements against them and I don’t feel that there are very strong hostile feelings towards them also. As a person who wrote very much on this theme and who knows both these societies so well, what do you think we can do to live toghether peacefully?

Conflict arises from scarcity or the perception of scarcity. We have to create societies capable of sharing resources, first among their own citizens and residents, who would then feel more generous and hopefully less scared of foreigners and strangers. In societies with ineconomic inequity, those with more are often willing to demonize foreigners and strangers in order to distract the attention of those with less. Those foreigners and strangers can be enemies in war, or the migrants and refugees who are treated as invaders. This is where literature and the arts play an important role in creating empathy for foreigners and strangers, because, in the end, we are all foreigners and strangers to each other, and even to ourselves. But literature and the arts have limits. We can create empathy in literature and the arts, but we, as writers and artists, cannot create the will in society to conquer fear, to resist demagoguery, and to welcome others.