“For our Ultimate L.A. Bookshelf, we asked writers with deep ties to the city to name their favorite Los Angeles books across eight categories or genres.” Based on 95 responses, Boris Kachka, Carolyn Kellogg, David Kipen, and David L. Ulin presents the 16 most essential L.A. literary novels, such as “The Sympathizer” by Viet Thanh Nguyen for the LA Times.

…

Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson, 1884

Raised in Amherst, Jackson was a widely-read travel writer, novelist and poet. Marriage took her west, where she saw that Native Americans were subject to tremendous injustices. Her scathing nonfiction account of U.S. policies had limited reach, so she wrote “Ramona,” an interracial romance set in Southern California designed to turn popular sympathies to Native Americans’ plight. It was indeed a huge bestseller. Although it chronicled land theft, racism and murder, the idyllic descriptions of the natural landscape resonated so much that “Ramona” is widely credited with sparking L.A.’s tourism industry. Noted 20th century critics dismissed the book, but recent scholars have revisited it as a muckraking romance. — CK

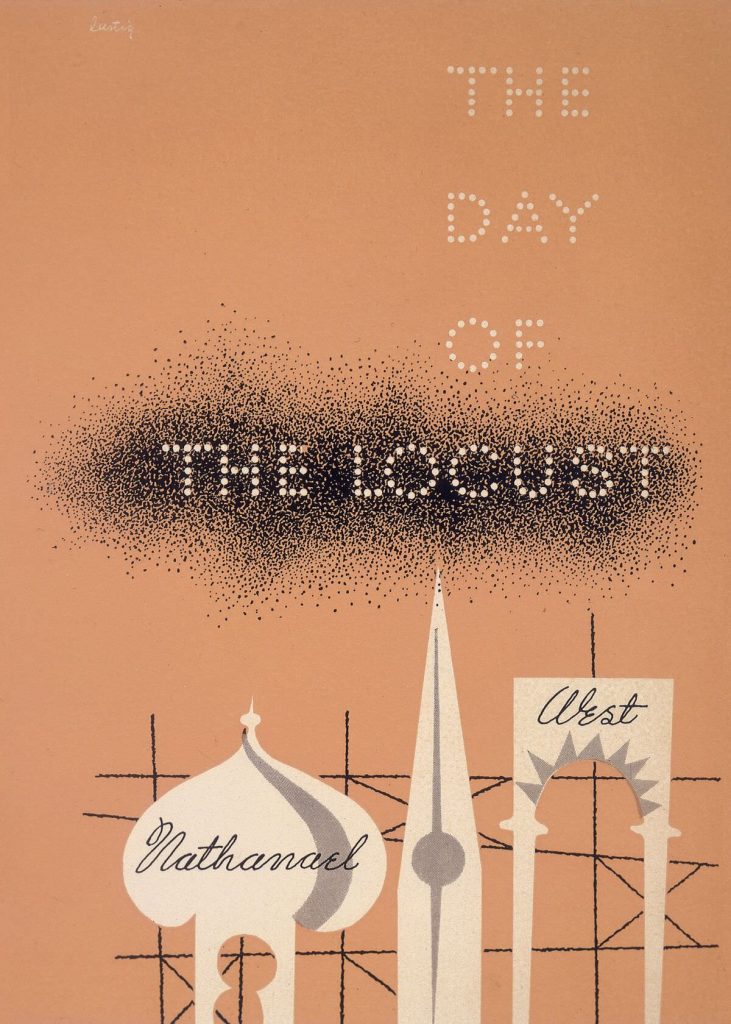

The Day of the Locust by Nathanael West, 1939

West’s final novel (he died the year after it was published) is a Hollywood masterpiece, a scabrous, pointed satire of the movie business and its considerable discontents. Revolving around a scenic painter named Tod Hackett, it imagines the city ending in a conflagration, and its gimlet-eyed look at the industry’s hypocrisies and contradictions is both of its moment and ongoingly relevant. “I can’t turn north from Sunset into the hills,” says Ivy Pochoda, “without this book popping into my head — every single time.” — DLU

Ask the Dust by John Fante, 1939

Fante’s second book is, along with “The Day of the Locust” and “The Big Sleep,” one of three novels published in the same year that marked a turning point in the way we write or think about Los Angeles, the emergence of the city it would become. The story of Arturo Bandini, a young writer living in a hotel on Bunker Hill, it has an almost hallucinatory intensity, and its portrayal of downtown Los Angeles during the Depression, as well as the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, are brilliant and profound. — DLU

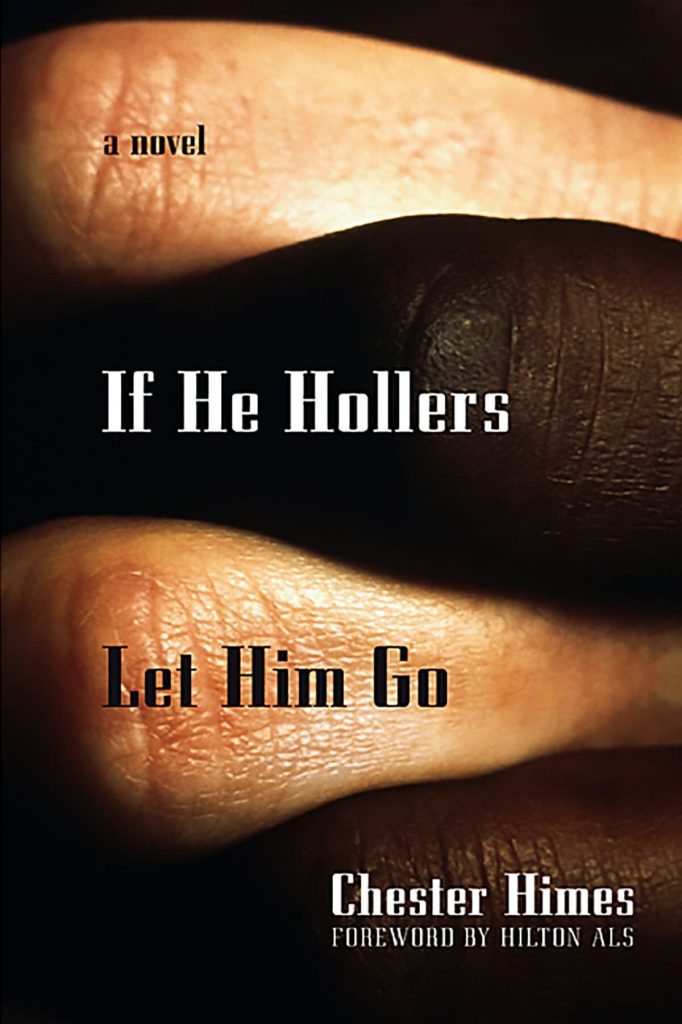

If He Hollers Let Him Go by Chester Himes, 1945

Himes’ debut novel was written out of the author’s experience in World War II-era Los Angeles, which he would later describe as having “shattered” him. The first-person narration is propulsive, driven by rage and loathing, and the portrait of the city as racially virulent is especially compelling, given the myth of Southern California as a land of opportunity. “A bitter bite out of redlined, racist Los Angeles,” says Greg Goldin — and he couldn’t be more correct. This is one of the city’s ur-texts, a precursor to the work of writers such as Wanda Coleman and Walter Mosley. — DLU

The Slide Area by Gavin Lambert, 1959

The British author, best known now for his novel and film “Inside Daisy Clover,” started out as a film critic. After moving to Los Angeles to work for director Nicholas Ray (they also had an affair), Lambert had access to the city’s film colony. In this underground classic, a screenwriter witnesses the hopes, confusions and corruptions of fame, from an aspiring starlet to an over-the-hill grande dame whose heirs await her demise. Lambert also writes with a keen eye for the city itself. — CK

City of Night by John Rechy, 1963

In this striking first novel, Rechy stakes out a previously under-recognized territory, that of gay hustlers during the late 1950s and early 1960s, “the world of Lonely America squeezed into Pershing Square … downtown now trapped in the City of lost Angels.” Rechy was writing autobiographically, but he was also aspiring to speak to (and for) a community that had long found itself catastrophically marginalized. “A stark hustler novel,” notes Carolina A. Miranda, “— one that inspired a tune by the Doors — chronicles the underbelly of Hollywood, where the only stars are embedded into the ground.” — DLU

Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion, 1970

One of the most beloved works of Angeleno literary fiction was written by a famous essayist. The story of Maria Wyeth’s disintegration, her freeway drives and her longing for her daughter, “captures the morally lost and unmoored feeling of the Californian creative class,” writes Jordan Harper, making it “both a time capsule and timeless.” Charles Finch adds: “The way Hemingway thought all American novels originated with Huck Finn, all L.A. novels originate with ‘Play It As It Lays.’ The simultaneous inward intensity of feeling and outward diffidence, the emotional and moral dangers of simulation, the hot alien beauty of the city … it superannuated ‘The Day of the Locust’ and gave either a template or at minimum an inflection to the fiction that came afterward.” — BK

Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis, 1985

“People are afraid to merge on freeways in Los Angeles,” Ellis declares in the famous opening line of “Less than Zero,” which Stephanie Danler says “belongs on this list forever and ever.” The privileged, sun- and cocaine-soaked teens of Beverly Hills use ennui to mask their fear of connection, but the book is as brave as it is bratty. It peeled back the Republican, Reagan-era sheen of Los Angeles to show beautiful rich kids who were not all right — and who, like the heroes of noir and punk, were more inclined to self-destruct than to ask for help. — CK

Golden Daysby Carolyn See, 1986

Who other than See would write an end-of-the-world novel with a happy ending? The story of two friends who met in the early 1960s, the book is a social novel and also, in its way, a social satire, until it turns into something else. The key to the narrative is See’s decision to imagine a nuclear apocalypse as a kind of reset, in which we can cast off the vanities of society. The result is a fantasia about “a race of hard laughers, mystics,” who “lived through the destroying light, and on, into Light ages.” It ends with its own affirmation: “Believe me.” — DLU

The White Boy Shuffle by Paul Beatty, 1996

No one takes satire farther, higher, lower or deeper than Beatty. His debut, an upside-down bildungsroman about the rise of Gunnar Kaufman from a Santa Monica scion of sellouts (“the whitest Negro in captivity”) to revolutionary poet doomsday cult leader, earned only one more vote for this list than his fourth novel, “The Sellout.” “Beatty’s humor is often the top note of discussions about his work,” says Michael Jaime-Becerra, “but settling there ignores the nuanced, wide-ranging social critique, nestled here in Los Angeles, that drives the work forward.” Dana Johnson adds: “He’s surprising and original, always.” — BK

White Oleander by Janet Fitch, 1999

What is it about mothers, murder and the Santa Ana winds? In a rollercoaster ride through the city’s foster system, via the child of a magnetic narcissist, Fitch nods to influences ranging from West to Didion while expanding the social strata — poor, working class, wealthy exiles, Hollywood perfectionists. Pico Iyer praises the novel “for catching not just the feeling and fragrance of L.A. but its fractured families and drift with rare lyricism and warmth.” Pamela Redmond considers it “a successor to Chandler and Ellroy in showing the dark bloody heart of LA.” — BK

Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon, 2009

Carolina Miranda loves “everything about” Pynchon’s stoner detective novel, especially “a circular plot that is so Los Angeles — you travel and travel and travel and you end up right back where you started.” The story begins and ends around Manhattan Beach, renamed “Gordita Beach” in honor of all the things P.I. hero Larry “Doc” Sportello loves best: non-nutritious foods, chubby babies and voluptuous femme fatales. We’re in the early ’70s, so Gordita inevitably suggests a kind of Fat City too, ripe for the plundering of rapacious real estate combines. It’s ideal for Pynchon’s recurring tragicomedy of America as the perfect wave that got away. — DK

The Barbarian Nurseries by Héctor Tobar, 2011

As a kid, Tobar watched his father deliver the L.A. Times; later he wound up writing for it before moving onto books. Signal among them is this cult novel fast outgrowing its cult. “The Barbarian Nurseries,” which Tod Goldberg calls “a broiling evisceration of suburban malaise,” tells the story of Araceli, an Orange County domestic worker. A crisis takes her on a frightening, picaresque odyssey across Southern California, including an encounter with an undocumented teenage girl that every legislator in Washington should read. The last chapters lead up to an impeccably calibrated, unsentimental ending that’s equal parts bitter and sweet. — DK

Elsewhere, California by Dana Johnson, 2012

Part of the Great Migration, Avery’s family moves from the south to South L.A., then to West Covina, and she tries to make sense of it all as a painter and assemblage artist. “Simply the best evocation of what it is like to grow up in Los Angeles that I know,” writes Lou Mathews. Aimee Bender cites it “because of how it moves between worlds/neighborhoods via language.” And publisher Dan Smetanka sums it up: “An L.A. artist’s entire life revisited in one day, as if Mrs. Dalloway traded in her flowers for Dodger tickets.” — CK

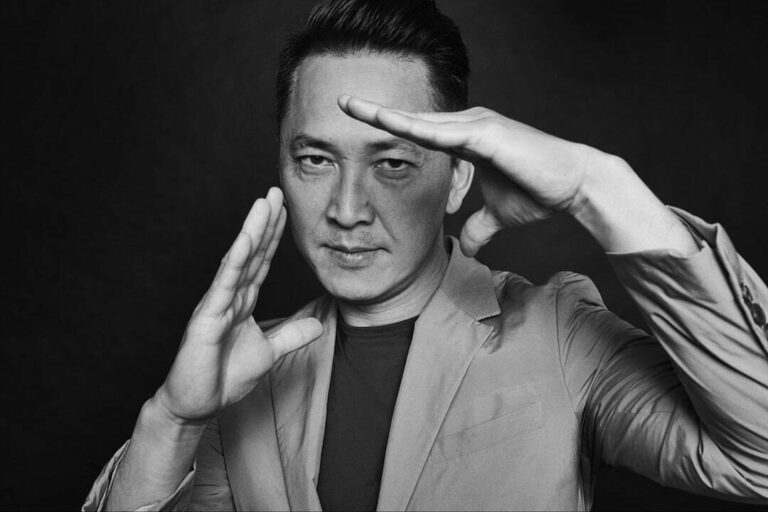

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen, 2015

“I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces,” Nguyen’s narrator says at the opening of this espionage thriller that is also an immigrant story, a satire of Hollywood and an inversion of colonialism. “I am also a man of two minds,” he continues, cluing us in to the truth that every immigrant sometimes feels like a double agent. This Pulitzer Prize-winning novel about a mole reporting on his fellow Vietnamese Angelenos to the Viet Cong is important for many reasons — not least, says Maria Hummel, “for its artful portraiture and eye on the way Hollywood manufactured perceptions of the Vietnam War.” – BK

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu, 2020

Willis Wu is only Generic Asian Man in the television crime serial that bounds his life, but he hopes to become something more. In this hilarious, heartbreaking novel, he lives with his family and friends in a cheap hotel above a Chinese restaurant, where people from a variety of nations are all labeled “Asian.” Yu explores stereotypes, racism, pop culture and the stories we tell through Wu’s experiences in a simulacrum of Hollywood. Narrated mostly in the form of a screenplay — Yu wrote for “Westworld” and “Lodge 49” — “Interior Chinatown” won the 2020 National Book Award for fiction. — CK