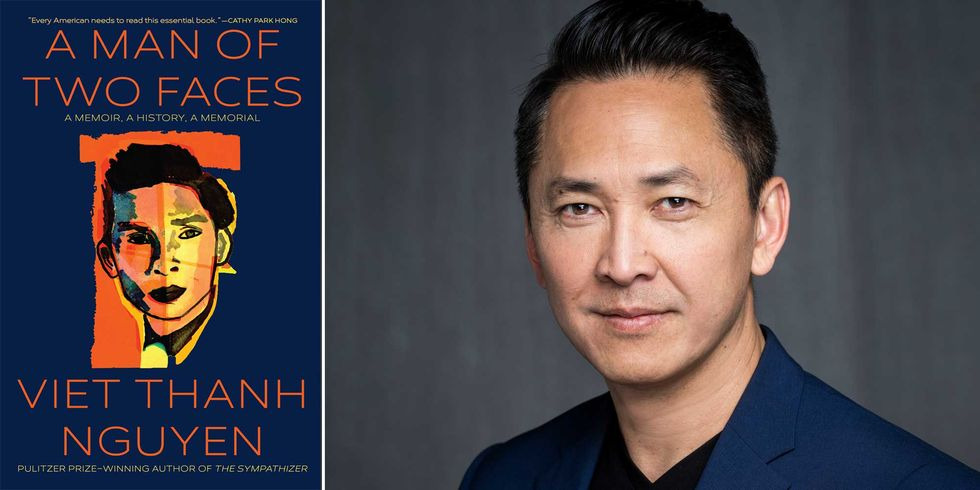

Viet Thanh Nguyen probes the primal rift in A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, a History, a Memorial. Gary Singh reviews Viet Thanh Nguyen’s memior, A Man of Two Faces for Alta Online

When Dionne Warwick won her first Grammy in 1968 for the song “Do You Know the Way to San Jose,” no one could have predicted that the fall of Saigon seven years later would trigger a massive influx of Vietnamese refugees. Among them was a hardworking couple, soaked in Catholicism, who opened one of San Jose’s first Vietnamese grocery stores in a decrepit downtown while raising two sons.

One of those sons was Viet Thanh Nguyen, who left the city after high school, became radicalized at Berkeley, found solace in critical theory, and eventually won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel The Sympathizer. Nguyen’s collection of short fiction, The Refugees, features a story called “War Years,” based on experiences growing up in his parents’ store, at Fifth and Santa Clara Streets.

In the early 2000s, the city of San Jose purchased the grocery’s building by force—the Nguyens sued to get a fair price—and the parcel became an unused parking lot until a 28-story residential skyscraper was built there, with a shiny new city hall directly across the street.

Nguyen’s new book, A Man of Two Faces: A Memoir, a History, a Memorial, deftly processes the psychological scars left by this history. The opening chapter is called “Do You Know the Way to San José?”

Nguyen was separated from his parents at the age of four, after the family first landed in Pennsylvania. Once they reunited, they came to San Jose. Colonization, war, forced displacement, childhood separation, and the loss of one’s country, Nguyen observes, are not mere “obstacles” to be overcome. “A handful of bad memories can be more indelible than a lifetime of good memories or mediocre ones,” he writes. “We notice the scar, not the skin. Being taken away from your parents is burned in between your shoulder blades, a brand you do not usually see until you examine yourself with the mirrors of your own writing.”

A Man of Two Faces pursues in heroic fashion the redemptive power of the writing life. If you are going through hell, write your way through it, which is precisely how Nguyen’s inventive formal structure comes to life. Much of the book is addressed to “you”—that is, the narrator writing to himself or, perhaps, his other face. Sometimes, as previously fictionalized in The Sympathizer, it’s the Karl Marx face corresponding with the Groucho Marx face. At other times, it’s the present-day narrator writing to his younger self, as when he recalls first watching Apocalypse Now: “Are you the Americans killing? Or the Vietnamese being killed?”

On the page, Nguyen plays with typeface—font sizes, center and right justifications, the name of the 45th U.S. president redacted with black rectangles. America is often spelled in bold uppercase with a trademark symbol: AMERICA™.

This intuitive, intrinsic sense of play energizes and animates the narrative while raising certain essential questions: Who is the real “you” to whom the author writes? Is he addressing only himself? Does the reader, in identifying with the “you,” become the second-person recipient? Or the second face? Or both? In writing to this “you,” Nguyen remembers—or “re members” or “dismembers”—both his current and previous selves. In the process, he comes to identify his inner conflict not as one of ethnicity or identity. The cliché immigrant condition, in which “minorities” are stuck between two cultures or somehow alienated from themselves, he suggests, is a falsehood. These issues arise not because there is an innate division between East and West, but because the colonization and conquest that brought the West into the East continues. As Nguyen wrote in his nonfiction study Nothing Ever Dies, all wars are fought twice: once on the battlefield and the second time in memory.

His inner crisis, therefore, is one of politics, not identity.

“You struggle with a political crisis, because the French brutally colonized Viet Nam,” he writes, “with AMERICA™, China and the Soviet Union taking sides in the resulting civil war between Vietnamese people with different visions of independence, sending you and millions of others into the diaspora, where you are left to re member yourselves.”

The solution, A Man of Two Faces insists, is not to become more Vietnamese, or more American, or to open a fusion restaurant. Rather, the only answer to colonization is decolonization. It is not enough, Nguyen argues, for minority writers to achieve “representation” in the literary canon or the vast vanilla hipsterdom of Hollywood. The goal should be what he calls narrative plentitude.

And then there’s the matter of the book as a memorial. As A Man of Two Faces progresses, Nguyen interweaves a heart-wrenching, multilayered tribute to his mother and the path she took to arrive in San Jose. In a series of deeply emotional chapters, we see the narrator grapple with whether he’s betraying her by spilling the details of her life and its effects on the family. Nothing but love pours off the page.

When the memoir finally circles back to the San Jose of his youth, we don’t know exactly how to make sense of the inept city-redevelopment czars who destroyed the family market. Nguyen even includes photos of the long-gone market, as well as of the shiny new skyscraper, currently the second-tallest building in town.

“This tragical farce or farcical tragedy is why your Karl Marxism needs your Groucho Marxism,” he writes, emphasizing that his parents and other Vietnamese refugees were so successful in gentrifying a downtown neighborhood 40 years ago that San Jose needed to gentrify it even further once the tech industry offered the city’s best shot at recognition. Now everyone knows the way to San Jose because it is a bedroom base for Silicon Valley.

For Nguyen, however, writing, as imperfect as it must be, is where he finally finds home. We can almost smell the blood and ink blend on the page as he moves through his recollections, or re collections, and in the process, works his way through the hell of memory, back to the city of the Dionne Warwick song.•