Elizabeth Strout, Jennifer Egan, and other best-selling authors are revisiting beloved characters from their prize-winning novels for Vanity Fair.

After Andrew Sean Greer won the Pulitzer Prize for Less in 2018, his agent issued a single warning. “Literally, she said, ‘You can’t write a sequel to a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel,’ ” Greer recalls. This month, he launches Less Is Lost, the sequel to Less, about an author named Arthur Less on a road trip across America. He joins four other Pulitzer winners and finalists who have recently done their own serializations.

Of major prizes awarded to American authors of literary fiction, the Pulitzer has a particular gravitas, due in some combination to its institutional backing (Columbia University), its longevity (the first awarded to a novel was in 1918, more than three decades before the first National Book Award for fiction and more than 60 years before the Pen/Faulkner), and the you-can’t-sit-with-us hauteur with which the board reserves the right not to award a prize at all. “There are no set criteria for the judging of the Prizes,” the Pulitzer website declares. The fiction prize is awarded to “distinguished fiction published in book form during the year by an American author, preferably dealing with American life.” This leaves a rather broad field.

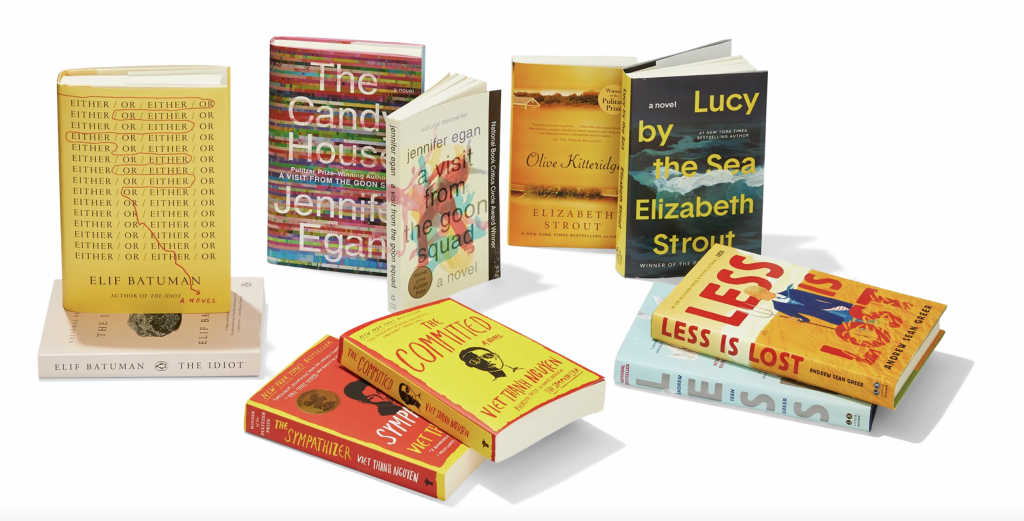

The five books in question are accordingly varied. Viet Thanh Nguyen, who won in 2016 for The Sympathizer, released The Committed in March of last year. The pair tell the story of the son of a Vietnamese mother and French Catholic priest as he serves as both a communist mole and a double-crossing underling (in the first) to a Vietnamese general, then escapes to Los Angeles following the fall of Saigon and (in the second) decamps the underworlds of SoCal for those of France. In April, Jennifer Egan came out with a companion to her genre-busting 2011 winner, A Visit From the Goon Squad, a formally inventive story cycle centered on the music industry. The Candy House turns various of that book’s minor figures major, continues messing with form, and zeroes in on the tech world. Elif Batuman’s Either/Or arrived last spring as well. Its narrator, Selin, an undergraduate at Harvard in the ’90s who thinks about sex in The Idiot (a finalist in 2018), finally has it. And now Elizabeth Strout gives us Lucy by the Sea, not just a sequel but a crossover: The writer-narrator of Strout’s My Name Is Lucy Barton (2016) and Oh, William! (2021) flees Manhattan with her ex-husband (and titular focal point of Strout’s last book) at the start of the pandemic to settle in fictional Crosby, Maine, hometown of Olive Kitteridge, the spiky antiheroine of Strout’s 2009 winner.

While Greer wasn’t aware of these books back in 2018, he might have directed his agent to other data. Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent, the 1960 winner, was the first in a series of six; Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, which won in 1986, the first of four. Philip Roth’s novel The Ghost Writer was a finalist in 1980; five Nathan Zuckerman–narrated follow-ups later, American Pastoral was the 1998 winner, after which Zuck returned three more times. John Updike won in 1982 and again in 1991 for the third and fourth books in the Rabbit tetralogy (plus a novella). Sure, this is a scant handful, and the Pulitzer board has awarded the prize (under the designation of novel from 1918 through 1947 and fiction after that) to 95 books, with 87 finalists, so for five authors to join the ranks of the above sinners in such close proximity is notable, particularly given that there is some anxiety about even employing the word.

“I’m supposed to call it a follow-up,” Greer tells me, “and not a sequel.” At first I chalk this up to a malaise over sequels, captured succinctly in a tweet by the writer Elizabeth Bruenig: “we’re living after the end of culture…nothing but reboots, sequels, copies of copies, simulations and nostalgia/kitsch until the sun burns out.” This isn’t the problem, though. It’s more a question of marketing: Greer’s newest book is a stand-alone, he says. One needn’t read the first to enjoy the second. In publicity material, Batuman’s book is billed as a “continuation,” Egan’s a “sister novel.” (“It’s about people writing sequels?” Batuman asks of this article. “That includes me!”)

In this cohort, it’s tough to impose a taxonomy. “Autofiction kind of lends itself to sequels because you’re the same person,” Batuman says, and it’s true that four of the books have characters who resemble their authors. Egan is the outlier here. “There’s a lot of me in there,” she says, “but not in the form of characters.” All of the authors in question started writing their follow-up long before the pandemic—except Strout, who wrote in feverish real time. “I had to try and get something down to remind myself that this was what my mind was doing at that point,” she says. “I mean [Lucy’s] mind, which meant my mind at that point.” All—Batuman, Egan, Greer, Strout, Nguyen—say that their revisited characters felt particularly compelling. But what author isn’t beguiled by their protagonist?

What is true and distinctive of all five authors is that each one wrote their follow-up during the reign of Donald Trump. “I didn’t think of it as a political book,” says Batuman of her experience writing The Idiot. Advance copies of the book “came out right around the pussy grabbing stuff, when we thought Trump was finished, and then it turned out he wasn’t.” She began to reconsider her first novel and decided to write Either/Or as the #MeToo movement swelled. Greer, whose protagonist bumbled Americanly abroad in Less, began a road trip through the Southwest in November 2016 and—inspired but heeding the warnings—started writing a brand-new draft with a brand-new central character, which never fully cohered. By 2018 he realized hapless Arthur Less was just the reluctant driver for the job.

“In the West, typically, when someone who’s a communist becomes disillusioned, they become liberal Democrats, they go flip in the exact opposite direction,” says Nguyen of his narrator. “I felt that if I just left the novel at that point, that’s what a lot of readers would assume, that he would just embrace the West, or America, or whatever. And I thought that that wasn’t his future.” Colson Whitehead, whose The Underground Railroad won in 2017, had planned to follow it with a humorous heist novel, “but then,” he said, “like a lot of people, after Trump got elected, I had to wrestle with where are we going as a country.” He postponed his other project and instead, three years later, released The Nickel Boys, another sober novel addressing systemic racism, which also won.

Whatever one might say about prizes—about the intrinsic peculiarity of ranking dissimilar artistic projects to select one as “distinguished” above all others—the Pulitzer illustrates a certain aesthetic and moral consensus. Great authors are early but good publishing is slow; if a book is timely, it’s because its creator was prescient. Egan, who started drafting The Candy House while she was on her Goon Squad book tour, but set it aside and only returned to it years later, puts it this way: “It almost felt to me like what I had was more relevant in 2016 than it had been in 2012, 2013, when I wrote it.” It was, she adds, “very odd.” But “this is what fiction writers do. We’re just soaking up all of the various strains and moods around us and writing from that, and obviously all that has happened also arose from those same strains and moods.”

So how to know when to call it quits on a theme? Strout already has a nice collection. Batuman has set plans to revisit her narrator at least once more—though next time, Selin will likely be in her 30s. (If Batuman were to stick with the year-by-year timeline, she says, “She’d still be buying her first Ikea futon, and I’ll be dead of old age.”) Egan has other projects in the works but doesn’t discount tugging again the threads in Goon Squad and The Candy House. “Three,” she says, “is a wonderful number.” By the time Nguyen began writing The Committed, he knew it would be the second in a triad; now that he’s beginning to conceptualize the final installment, he’s running into existential hurdles. “I’m debating whether he lives or dies,” the author says of his nameless narrator. “And so if he is my alter ego, it is a meditation for me….”

What, then, of our most recent—and first post-Trump—winner? “My characters tend to live book-length lives,” says Joshua Cohen, author of The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, in response to whether a follow-up is in his future. “Not that I kill them off, rather I’m afraid I exhaust them, or they exhaust me, and we both exhaust the reader. Each book is a chance to make the world anew—the world from a voice—and if I’m going to repeat myself, and repeat my blundering, I’d prefer to do so in private and not in literature. It’s only on the page that I—that all of us on this one trashed earth—get a do-over.”