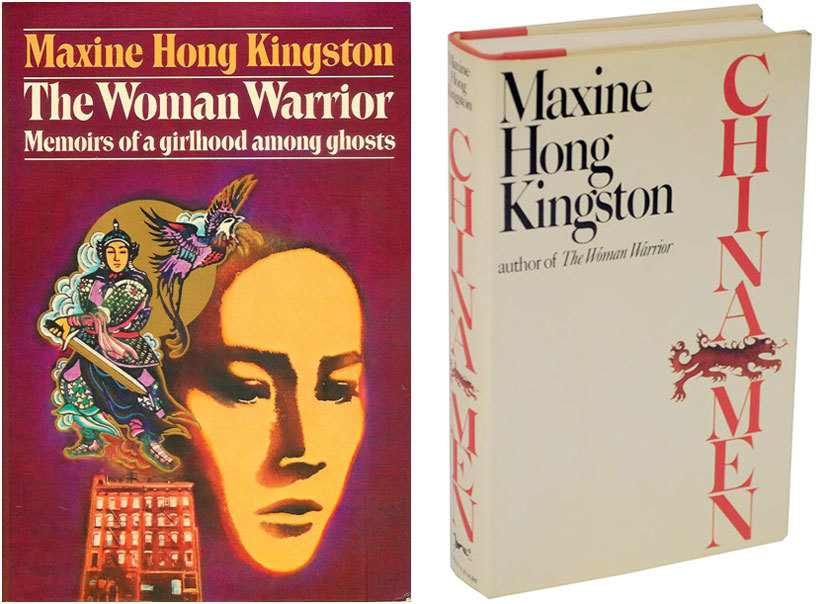

Released this spring by Library of America, Maxine Hong Kingston: The Woman Warrior, China Men, Tripmaster Monkey, Other Writings brings together Maxine Hong Kingston’s two classic, genre-defying memoirs, The Woman Warrior (1976) and China Men (1980), and her 1989 novel Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book. The book’s editor is Viet Thanh Nguyen, whose debut novel The Sympathizer won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in Fiction. His other works include another novel, The Committed; The Refugees, a short story collection; and two works of nonfiction, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, and Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America. A former student of Maxine Hong Kingston’s at the University of California at Berkeley, Nguyen is the Aerol Arnold Chair of English and Professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California. Nguyen answered our questions about Kingston and her work via email for the Library of America.

Library of America: Even as The Woman Warrior and China Men are now acknowledged classics, they continue to elude categorization. Earlier editions presented both books as memoirs but it’s increasingly common to see them referred to as novels. Kingston has stated, “This confusion really makes me feel good.” Can you speculate as to why she might feel that way?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think The Woman Warrior and China Men foreshadow a trend we see increasingly today, which is the book that refuses easy categorization in an established genre. For example, “autofiction” is rather popular today, a genre that blends fiction and autobiography. Arguably, The Woman Warrior and China Men are autofictions, where a character named Maxine (in The Woman Warrior) may or may not be Maxine Hong Kingston the person or the author, and whose life, real and/or imagined, mixes with her memories and made-up stories of family members. China Men also features family members, but who knows what is fact and fiction in the tales that the author weaves about them?

For both of these books, “memoir” and “novel” (or “fiction”) are inadequate, or confusing. Kingston is not shying away from that confusion and embraces it, because, I think, the inadequacy of traditional genres to her lived experience is an expression of how so-called minorities may find traditional genres insufficient, in different ways, to cope with their lives and histories. Kingston, for example, has mentioned how she had to make up details of her parents’ lives in her books in order to obscure how they came to the United States, since they were undocumented.

Meanwhile, as the American-born daughter of Chinese immigrants, she had a filtered, changed, possibly distorted version of “authentic” Chinese culture, leading her to adapt Chinese culture to her own needs and perceptions. This led to the controversy over her use of the Fa Mu Lan legend in The Woman Warrior, with her critics accusing her of getting the facts wrong, while her defenders argued that the immigrant and diasporic experience transforms Chinese culture and erodes notions of origin and authenticity. In that environment, the “fiction” of the immigrant experience trumps the “fact” of the homeland, and Chinese legend is reworked as Chinese American myth.

LOA: It’s fascinating to learn that Kingston originally conceived of her “mother-book” (The Woman Warrior) and her “father-book” (China Men) as a single vast work. How does China Men complement or extend our understanding of the lives depicted in The Woman Warrior?

Nguyen: The Woman Warrior opens with the justifiably famous scene of the no-name aunt who commits suicide in the family well after an unspeakable transgression. From there, the book looks closely at the lives of daughters, mothers, and women in Chinese and American societies, setting a template for a good deal of Chinese and Asian American literature to follow, most notably in Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club. I wonder why Kingston hasn’t gotten more credit, especially from her critics who are Chinese American men, for foregrounding the lives of Chinese immigrant men in China Men. I don’t think of China Men as being a compensatory work for The Woman Warrior but, as you say, a complementary work.

While there is a single-volume edition of both books, it’s not widely available, and I wish there would be a more accessible paperback, maybe even a standard or scholarly volume, that included both books, to better realize Kingston’s original ambition. Because what we see in China Men is not only a focus on men and their specific experiences, but a more explicit focus on the law. The Woman Warrior’s predominant gesture at history is through legend, the Fa Mu Lan story among others, while China Men’s gesture at history is through its important section on the racist American laws directed at Chinese immigrants. These laws shaped the lives of Chinese immigrant men by turning them into second-class people whose lives were more vulnerable to violence, terror, exploitation, discrimination, and early death.

These laws also prevented the immigration of most Chinese women, which is arguably a genocidal attempt by the U.S. government to prevent the formation of Chinese families. The distortion of the life chances of Chinese immigrant men inevitably affected the Chinese immigrant community as a whole, and shaped the relatively scarce population of Chinese wives, lovers, and daughters. The ripple effect of those laws would be evident in The Woman Warrior, where Chinese immigrant women and Chinese American women would grapple not only with Chinese patriarchy (as other Americans might focus on) but also with an American racism that also assaulted the Chinese family. Gender and sexuality would be inseparable from race and nationality—understanding this is part of the cumulative effect of reading these two books side by side.

LOA: Kingston’s novel Tripmaster Monkey: His Fake Book is arguably her most audacious work, honoring as it does Walt Whitman; the spirit of the 1960s counterculture; and a host of East Asian cultural and artistic traditions. How would you describe Tripmaster Monkey to someone who’s never read it?

Nguyen: Tripmaster Monkey is a Great American Novel, but it’s also a Great Asian American novel, and the overlap between these two is part of what makes Tripmaster Monkey so powerful. Featuring a bohemian, counter-cultural Chinese American playwright/loudmouth in Wittman Ah Sing, the novel centers Asian American culture of the 1960s and shows how saturated it is with the politics of protest, rebellion, and experimentation that characterized the youth, popular culture, and new social movements of that decade.

Naming its protagonist after Walt Whitman and evoking his poem “I Sing the Body Electric,” as well as Langston Hughes’s line “I, too, sing America,” Kingston creates an antihero who descends from the complexities and contradictions of the United States. On the one hand, the democratic aspiration of Whitman; on the other hand, the critical rejoinder from Hughes, featuring “the darker brother” who is denied American opportunities. Tripmaster Monkey is about a United States that should include and acknowledge Asian Americans, and is also about Asian Americans as embodiments of democratic energies that the country needs.

At the same time, the novel is a lot of fun, full of casual drug trips, language play, idealistic optimism, youthful foolishness, and assertive pride in the history of Asian American accomplishments, from literature to Hollywood. A reader can learn a great deal about San Francisco, Berkeley, the 1960s, and Asian America from this novel.

LOA: Library of America’s Kingston volume includes “Cultural Mis-readings by American Reviewers,” her determined, entertaining 1982 essay about misconceptions of her work by critics. Do these sorts of misunderstandings still occur with regard to her work—and, by extension, the work of subsequent Asian American writers?

Nguyen: Perhaps not so much with Kingston’s work anymore. She’s an icon by now, the winner of many major awards, a canonical figure in American literature. She might be misread in different ways, as any writer can be misread, but it would take considerable ignorance to misread her work in regard to Asian American issues. I think critics know they need to do their homework, relative to her.

That being said, cultural misreadings of Asian American work as a whole probably still do happen. Anecdotally, some Asian American writers, established and aspiring, have recounted how their work has been rejected in that mostly unrecorded world before publication. The rejection slips, the face-to-face comments that express misunderstanding in some way or another. And once books are published, especially from newer writers who are not yet protected by reputation and readers’ familiarity with their work, ethnicity, or history, the potential for misunderstanding or misreading is there. Sometimes this is manifest as incomprehension or oversight of some critical element of the work or the background from which it springs; and sometimes this is manifest positively, perhaps through reading the work or the author as being representative of their culture or community, whatever that is. How often are white writers taken as representative of their culture or community, whatever that is, versus so-called minority writers?

The burden of representation, which too often falls unfairly on the shoulders of so-called minority writers, is a result of misunderstanding, often by the so-called majority but sometimes by the Asian American writer’s “ethnic” community as well. That’s how Kingston ended up feeling not only misread by other Americans but by some Chinese Americans as well. That kind of misunderstanding—feeling pressured by one’s own “ethnic” community—definitely still exists.

LOA: Lastly, a human-interest question. What is it like to have Maxine Hong Kingston as a writing teacher? (In Hawai‘i One Summer, she gives us a tantalizing glimpse: “I tell the students that form—the epic, the novel, drama, the various forms of poetry—is organic to the human body.”)

Nguyen: I’m a teacher myself, and I have hope that while education is sometimes immediately felt, at other times it is experienced as a delayed effect. Sometimes the teacher is not ready for the student, and sometimes the student is not ready for the teacher. The latter scenario is probably a fair description of me when I was nineteen or twenty and sitting in Maxine Hong Kingston’s creative nonfiction writing seminar at UC Berkeley. To be admitted was a huge privilege; there were only fourteen students. And yet, every day, I would walk into class, sit a few feet from Kingston, and every day—I fell asleep.

It wasn’t Kingston’s fault. I was tired from being up late, studying and doing political activism. And I was probably suffering from my own emotional issues, as my journal from that time records, and as I wrote about in my essays for Kingston. Thirty years later, I’ve finally gone back to writing about what I was going through then. Kingston couldn’t help me then because I wasn’t ready to be helped. I had to learn how to be a writer before I could go back and listen to her work and her teaching.

When she says that form is organic to the human body—I feel that. So much of my best writing comes not only from my mind, but also from my body. From feeling and pursuing feeling, from letting the writing emerge organically from some place inside of me that I’m not fully aware of. The formal decisions I make are often only semi-rational, sometimes irrational, which I don’t mean in a negative way. As a teacher, I don’t think I can teach students how to listen to their body or how to let go of their rationality, just to name two things that could be useful to writers. I can only say these things and point the way, as Kingston did for me and other students.

She showed the way, and it would take me a very long time to find my way. That’s partly what it means to be a writer—each of us has to find our own way, even if we’re lucky enough to have someone show us the way.