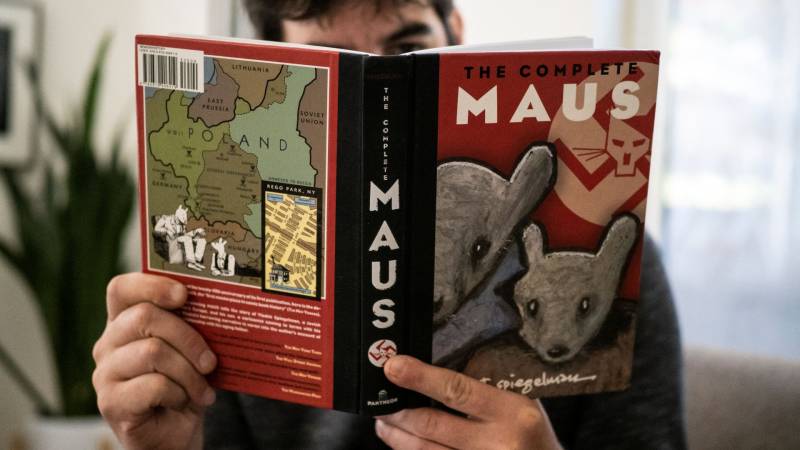

A Tennessee school board last week voted to remove the Pulitzer-prize winning graphic novel Maus from an 8th grade course on the Holocaust. And that’s just one of many examples of recent bans instituted by parents, activists, school boards and lawmakers. According to the American Library Association, it has seen an “unprecedented” number of book bans in the last year. But unlike previous waves of book bannings, this latest wave has a different tone and tenor; bans are often targeted at books that center on the experience of diverse characters or are written by authors of color. We’ll look at why book banning is spreading across the country and what might be done to reverse the trend with KQED Forum.

Speaker 1:

Did you know you’re listening to a podcast from KQED in San Francisco? Well, we’re having a pledge drive because 62% of our budget comes from listeners. So, give what you can at KQED.org/donate. That’s KQED.org/donate.

Speaker 2:

Support for KQED comes from Sutter Health, dedicated to making healthcare are accessible. From regular checkups to virtual visits to preventative screenings, the Sutter Health network is committed to helping patients stay strong and healthy, today and every day. More at SutterHealth.org.

Mina Kim:

From KQED in San Francisco, I’m Mina Kim. Coming up on Forum, a Tennessee school board last week voted to remove the Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel Maus from an eighth grade course on the Holocaust, the latest in a string of recent book fans. Other frequent targets have include All Boys Aren’t Blue, Genderqueer, and The Bluest Eye. The challenges and bans, which the American Library Association has called unprecedented in number, have been initiated by parents, school boards, even governors who’ve called for investigating and prosecuting school officials and librarians. We look at why book bans have been spreading across the country with speed and intensity, after this news.

Mina Kim:

This is Forum, I’m Mina Kim. A mayor in Mississippi is withholding funds from its public library until it removes books with LGBTQ characters from the shelves. Texas Governor, Greg Abbott has called for investigations and prosecutions for “pornographic school material”, while Texas State Representative Matt Krause has told districts to identify books for removal that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.

Mina Kim:

These calls for book bans by politicians and parents prompted writer Viet Thanh Nguyen to write a New York times opinion piece last week. Nguyen is the author of the Pulitzer Prize winning novel, The Sympathizer, and its sequel, The Committed. He joins us now. Welcome to forum, Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Hi, Monica. Thanks for having me.

Mina Kim:

Glad to be here. And it’s Mina, actually.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I’m so sorry.

Mina Kim:

No, no worries. So, your New York Times essay is titled “My Young Mind Was Disturbed By a Book. It Changed My Life.” What was this book?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

It was a novel titled Close Quarters by the American novelist, Larry Heinemann, and I encountered it in the San Jose Public Library area when I was about 12 or 13 years old. And it’s an novel about the Vietnam war. And I was very curious about the war because I was a Vietnamese refugee. And in reading the book, I was quite shocked and dismayed, because what happens in the book is that American soldiers kill a lot of Vietnamese people. And in the climax, they gang rape a Vietnamese woman. And I thought, “Wow, this is how we Vietnamese people are seen by Americans.” It was very upsetting to me, and I hated the novel and I hated Larry Heinemann for many decades.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

But what happened was that I reread the novel as an adult, as a writer, and I realized that Heinemann was right, because what Heinemann wanted to show was how war brutalized civilians, but how war also turned nice American boys into remorseless killers and rapists. And he didn’t want to give readers like me a way out by editorializing or sentimentalizing or humanizing the Vietnamese, because that was not how American soldiers saw us, and he just wanted readers to confront their own discomfort. And eventually, I had to.

Mina Kim:

And despite what an basically horrifying impression that book left on you as a young person, it sounds like you are really glad that, well, as you write in your piece, that you didn’t complain to the library or petitioned to have librarians take the book off the shelves, nor did your parents. Why was it important for you to make that point?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think it’s important because I’m as a parent right now, I also think about what my son is reading and what he’s encountering and what he’s dealing with. And of course as a parent, I want to protect him and be there for him for difficult moments, but I also realize that part of growing up for everybody is that there will always be moments where we encounter things without guidance or help from our parents or from other guardians, and that’s a part of maturing and learning had to deal with things.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

When it comes to things like books, I can’t imagine much more of a safer space than books for encountering hard lessons. It’s much easier than encountering hard lessons on the playground, for example. And so, at that time it didn’t even occur to me that I could complain. And even if I could complain, I don’t think I would’ve done it because I understood that part of the joy of books was learning things, learning new things, which could be uncomfortable. And because I was left to deal with it on my own, I did figure it out. That was far from the only book that made me question things and disturbed me in various ways. For better, for worse; it turned me into a writer. So, maybe the adults out there don’t want their children to become writers. I mean, it’s a legitimate point.

Mina Kim:

Yes. You have talked about, though, how books are inseparable from ideas and that’s what’s at stake. What do you see as the impact of removing books, banning books?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, the impact I think is precisely to prevent the discussion or even acknowledgement of certain kinds of ideas. And of course, the reason why that’s problematic is that in a democratic society, in a society with a strong civil society, we should be having discussions about ideas of all different kinds from the provocative and interesting to the difficult.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

And again, that’s how children learn. And of course they learn by looking at what their parents and adults are modeling. And they’re not stupid. I mean, they have iPhones. So, I’m sure they’ve heard about the book banning and about these books in particular, and what’s being modeled to them. What’s being modeled to them is that adults say, “We shouldn’t even be talking about certain kinds of things.” That’s a bad model to present. And if the adults in question are having serious concerns about certain kinds of ideas or texts or books and so on, I think it’s legitimate to have those concerns, but the response should be, especially on the part of a school board, to have things like a public forum, a public discussion and so on, and model a way of having dialogue for the children and the students.

Mina Kim:

What do you think are some of the motivations that are driving these recent challenges to books and calls to ban books? One of the lines in your piece that I was really struck by is you talked about how it seems that people are seeing a danger in empathy, and I was really struck by that. I think that’s in part possibly a motivation, but definitely also an impact. Can you explain that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Sure. I mean, I think there’s various motivations for banning books or banning ideas or preventing a certain words from being spoken, and it comes from all points of the ideological spectrum. But in this particular case, especially around the question of empathy, and with books like Maus for example; I mean, part of the reason why these books are so powerful is that they’re beautiful artistically, but they’re also very seductive in terms of their storytelling abilities. And part of the seduction from a powerful story is that the story gets us to empathize with the characters in a story. Therefore, we see the world from their eyes. We see history from their eyes.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

For this particular group of parents or this school board, I think the danger of empathy in this case is that they may not want their children to see the world from these particular eyes that, for example, Art Spiegelman is working through in Maus. Because if their children did see the world through the eyes of Jewish characters or Black characters or queer characters and so on, they may be sympathetic or empathetic to the plight of these particular types of characters, and therefore, the people in the real world. And if parents or politicians are opposed to these groups of people, they have a vested interest in not wanting their children to empathize or to be open to these people’s experiences.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

And of course, it’s related to the politics of the country as a whole. It’s quite obvious that we’re a divided country, we’re divided to various around various kinds of political and social issues. The country is undergoing tremendous change both now, but in the last several decades as well as different groups, such as Jewish Americans or queer people, LGBTQ people, have asserted their histories and their identities. And there are some people out there who don’t want to hear about these identities, or don’t want to acknowledge these particular groups’ histories and experiences, and they know that empathy is a key battleground for how to both open up society in a certain way, but also how to prevent society from opening up.

Mina Kim:

Yes. It’s an interesting point. By the same token as you’re describing how it can help us find empathy and relate to characters and expand our ability to love and appreciate others, that when you are targeting a book for being banned, the message can also be that you don’t have to understand this person or walk in their shoes. You can dismiss their experience as well, which I think is part of what you’re getting at here in terms of the danger.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I just want to say that, as I said, I’m a Vietnamese refugee, Vietnamese American, Asian American, person of color. I grew up going to the library and reading almost wholly books about white Americans, and I didn’t question that. I live in the United States. But it gave me tremendous empathy for white people. I think I know a lot about white people from reading all these books. That was the nature of Americanization.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

But in other words, that we who are newcomers, or we who are considered different by whoever in American society are always being forced to empathize with whoever the dominant population happens to be. And so of course, I think that there is a resistance to empathy in the reverse direction. People who have never been forced to empathize with people who are different from them, they resist that urge. And of course, honestly, I resent that resistance given that I’ve been required to empathize with the dominant classes my entire life.

Mina Kim:

Can I ask you how you handle problematic or racist work at home with your own kids, as you’ve been talking about how you think about it a lot in terms of what you present your own children or what you allow them to look at and how?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I think what’s important to acknowledge here is that, for example, I have an eight year old son. I’m not bringing home Mein Kampf to him, okay? So in other words, when we say the word, something like racist, for example, or sexist; it’s a broad brush. And I think that in a lot of circumstances, it’s very difficult to say of a book, for example, that it’s utterly and wholly racist or utterly and wholly sexist and so on. And in fact, a lot of works are probably very complex in terms of what it is that they present.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So, the example I talked about in the essay for the New York Times was Tintin, the comic book series from the Belgian artist Hergé which I’d read when I was a child in the San Jose Public Library. I love the books. They’re beautiful, they’re very compelling to read. I introduced my son to them and he loves them too. And of course rereading them as an adult, I realized, well, Hergé was a product of his times. The books are replete with racist and colonialist images, but those images do not say everything about his work. Like I said, the books are riveting in terms of storytelling and they still are.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So instead of telling my son, “Oh, we should not read these books because of these particular kinds of images,” I tell him, “Look, I’m glad you enjoy them. I enjoy them too. But I think we should at least notice how Chinese, Native Americans, Black Africans are being depicted here and why this might be problematic.” What I want him to know is that these images have existed historically, and they still exist today.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

So for example, I bring him to France quite often. The Native American representations in Hergé from the 1950s are still there in France. The depictions of Black Africans, which are really atrocious, are still being seen in parts of Europe and are not being questioned. He’s going to see those images on his own eventually. I’m glad that we’ve had this discussion now so that when he does see them, he knows how to make sense out of them.

Mina Kim:

Yeah. I really liked your point that you do try to put it into context, but that you also try to make sure that he has access to other stories about people that Hergé has misrepresented, which I think is a really important point.

Mina Kim:

We’re talking with the Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, which won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. He’s also a professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature at USC. We’re talking about the recent wave of book bans, a trend which the American Library Association is called unprecedented, and I want to invite you, our listeners, to join the conversation.

Mina Kim:

(866) 733-6786 is the number to call. Has a book you grew up reading, been banned? What’s your reaction to that? Curious also how you deal with difficult or problematic books as a parent or a teacher. We’ll have more after the break, stay with us. I’m Mina Kim.

Speaker 5:

Support for this podcast comes from Stanford Continuing Studies, now offering over 140 online courses in all subjects. Spring registration is underway and most class is start the week of March 28th. Registration at ContinuingStudies.stanford.edu.

Mina Kim:

The battle over books is heating up and that’s what we’re talking about this hour on Forum. I’m Mina Kim, and we’re talking with Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature at USC.

Mina Kim:

Nguyen wrote the recent New York Times oped, “My Young Mind Was Disturbed By a Book. It Changed My Life.” You, our listeners, are invited to join the conversation. Has a book you grew up reading been banned? What was your reaction to that? What are your thoughts or questions about this recent wave of book bans? (866) 733-6786 is the number. (866) 733-6786. You can get in touch on Twitter or Facebook or Instagram at KQED Forum. You can email us, forum@kqed.org.

Mina Kim:

I want to bring into the conversation now Elizabeth Harris, a reporter for the New York Times. Harris covers books and publishing for the newspaper. Elizabeth, thanks so much for being with us.

Elizabeth Harris:

Thanks for having me.

Mina Kim:

So, could you put in context for us the scope of these book bans across the country? You’ve reported that they’re at a pace not seen in decades. Who or what is driving these book challenges and bans, this pace?

Elizabeth Harris:

Sure. So I mean, book challenges are really a regular feature of school board meetings. They come from the left, they come from the right, they come from a lot of people who don’t see this as a political or partisan issue at all. They’ve been around for a very long time. But the inquiry and the politicization that’s happening right now does feel really different to people who track these sorts of things.

Elizabeth Harris:

As you mentioned at the top of your show, I mean, some state governors are making an issue of this in Texas, in South Carolina. In Virginia, it was part of the race for governor. It appeared in campaign ads. So, that level of attention on it is different.

Elizabeth Harris:

It’s appearing in state legislatures. There’s some legislation that have been introduced in different parts of the country. There’s a bill in Oklahoma that would essentially ban… Let me just make sure I get this right, it would prohibit public school libraries from keeping books that focus on sexual activity, sexual identity, or gender identity in the library. That’s new.

Elizabeth Harris:

Another piece of this is, traditionally we think of this as an issue where someone watches, sees their kid bring home a book that they personally find objectionable, and then they bring it to the school or the district and it unrolls from there. But a big part of what’s happening now is parents are seeing lists circulating on social media of Google Docs and spreadsheets of books that people consider, some people consider to be problematic. And they might have quotes pulled, one paragraph of a 200 page book pulled out that people find objectionable, or one or two squares of a graphic novel.

Elizabeth Harris:

One thing that leads to is that a certain number of books are being challenged all over the country. So there’s, let’s see, what is it? All Boys Aren’t Blue has been targeted for removal in at least 14 states.

Mina Kim:

Wow.

Elizabeth Harris:

And so again, that’s been on a lot of those lists that have been circulated. And some of them are by parent groups, some of them are by activist organizations like No Left Turn in Education, which have a particular agenda and that kind of thing. So, those are how it’s changed now.

Mina Kim:

Yeah. What you’re describing really sounds like a coordinated effort with a strong political apparatus backing it up. I know that two groups have been mentioned at the forefront of these attacks, Moms for Liberty and No Left Turn in Education, who you also noted as well in your piece. Can you tell us about them?

Elizabeth Harris:

So, Moms for Liberty, there’s an umbrella organization and then lots of local chapters around the country. I spoke to one of the founders of the umbrella group, and she was saying that they don’t distribute lists themselves, but the local chapters do, and I saw a number of those lists.

Elizabeth Harris:

What she was saying is, their concern is twofold. They don’t want parents to be attacked for asking if books are appropriate for their children, and then the main theme that you sort of articulated to me was a concern about sort of sexuality, basically, and books about sexuality and parents. Either things that some parents don’t think is appropriate for their children at all, or might only be appropriate in a sex ed class, for example, just being on the shelf in the library.

Elizabeth Harris:

And for Moms for Liberty and for a lot of Republican politicians as well, this issue is being framed as a parent’s rights issue, and every parent has the right to direct the upbringing of their own child, and so parents should be making these decisions as opposed to schools. And then on the other side, people are saying, “No, I would like educators and librarians to be making decisions about curating a collection of books that reflects the entire community,” and that kind of thing.

Mina Kim:

School libraries, though, they already have mechanisms in place, right, to stop individual students from checking out books that parents disapprove of?

Elizabeth Harris:

Yeah. A lot of places you can, if you really don’t want your child reading about, I don’t know, witchcraft, whatever it is; you can give a list to the local library and the kid can’t check it out. So yeah, that does exist.

Mina Kim:

Yeah. This sounds like it goes beyond. And then also what’s been really striking is the effort among some of these politicians, governors, lawmakers; as you describe, efforts that have gone as far as bringing or trying to bring criminal charges against librarians, educators. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Elizabeth Harris:

So, there have been some complaints that have been brought to sheriff’s offices basically, and they then get referred to local prosecutors who have to decide whether or not to charge anybody. In one case in Wyoming, this happened with library employees. And in Florida, it actually happened with a book itself.

Elizabeth Harris:

When I spoke to free speech advocates and lawyers, they weren’t concerned that these sorts of charges were going to stick. It’s an incredible long shot. But when I spoke to librarian and groups that supply librarians and things like that, they were saying that it doesn’t really matter, ultimately, if these are incredible long shots as charges, right? Because if you live in a community and suddenly you are publicly accused of pedaling pornography to children, that in itself is sort of punishment enough, and also just sort of the specter of having to maybe defend again charges of maybe having to hire a lawyer is very frightening for people. And some people see this as just primarily an intimidation tactic, and possibly an effective one.

Mina Kim:

But it sounds like it’s already having an impact as you say. Well, we’ve got some calls coming in. Let me go to Lisa in San Francisco. Hi, Lisa.

Lisa:

Hi. So, what I’m wondering is, maybe some of these bans are actually having an ironically opposite effect. I remember as a child, my mother tried to ban me from reading Mad Magazine, for instance, and all I did is I just went over to my neighbor’s house and read it there. And I noticed that Maus has skyrocketed now to the best sellers list on Amazon.

Lisa:

I mean, I’m very much against these bans. I’m very pro first amendment, but it seems to me, it may have ironically the opposite effect of bringing way more attention as being a disapproved piece of literature. A lot of kids, especially middle schoolers and high schoolers, they like to do the opposite of what the authorities are trying to impose on them. Do you see what I mean? [crosstalk 00:22:49]

Mina Kim:

I do see what you mean. Let me see if Elizabeth is also seeing the same thing. I know you need to leave us, Elizabeth, but have you been seeing that it’s having that effect?

Elizabeth Harris:

It really depends. There are some books that’s true for, like Maus. It is a big book, right, and people have heard of it and they can go on Amazon and immediately go find it.

Elizabeth Harris:

Individual books don’t tend to get big headlines about them, right? So, Maus gets banned and people are going to go buy it. But most of the books this happens too aren’t aren’t books everyone’s heard of, and they’re not going to lead CNN or whatever, whatever level of attention Maus got. So, I would say that it does happen and it can happen, but I don’t think that’s a common occurrence necessarily. But I would actually be curious to hear what your other guests think about that. They might know more than me.

Mina Kim:

Viet Thanh Nguyen, have you heard that as well in terms of just the impact of these bans sometimes just making them even more enticing in the public market?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I don’t have a quantitative sense of this, but of course typically the book bans bring attention to the most famous works that we have, like Maus, like Fahrenheit 451, like Beloved. Those books don’t need additional sales encouragement. So, I think it might be accurate, because for example, the list in Texas is about 800, 850 books. I don’t imagine the overwhelming majority of those books are seeing a major boost in sales that would just reflect the nature of the book industry in general. So, there probably for the mid-list author and so on or non-popular books, it’s probably more of a detriment than a boon.

Mina Kim:

Yeah. The lower profile books really can get hurt by this. We’re talking with Viet Thanh Nguyen, and also Elizabeth Harris, a reporter for the New York Times. Thanks so much for talking with us, Elizabeth. Really appreciate you giving us some context here.

Elizabeth Harris:

Thank you.

Mina Kim:

I’d like to bring into the conversation now, Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America. Suzanne, thanks so much for being with us.

Suzanne Nossel:

Thanks for having me.

Mina Kim:

So, people have noted that the last time they saw book bans with a very high degree of intensity was in the 1980s. You have said that these are not the challenges of yore. Can you talk about what you’ve noticed about these challenges and how they’re different?

Suzanne Nossel:

Sure. I mean, some of the points we’ve touched on, but I think that the main thing to understand is these are not spontaneous outpourings from concerned parents in particular communities. This is part of a systemic effort. It’s not the Red Scare, but here at PEN America, we’re calling it the Ed Scare because it is a state of maneuvers, including more than 120 bills that have been introduced in state houses across the country to ban certain material from school room and even higher education curricula. These are materials that deal with issues of race, racial justice, how slavery is taught in courses on American history. And so, it’s a frontal assault on the freedom to think. And these book bans have hit a nerve where I think those who are trying to pull back on the consequences of demographic change in this country and the rise of a more progressive and understanding approach to racial and ethnic differences, the embrace of different narratives, people being able to see themselves as fully American regardless of background; there is a potent backlash that has been mobilized against this.

Suzanne Nossel:

We see it in the efforts to curtail voting rights. We see it in these curriculum bans, and we see it in book bans. That’s an issue, it doesn’t hit the pocket book, it hits the book bag. So, it’s very personal for parents and communities across the country. I think those who are trying to orchestrate this backlash have seized on it because it could hit so close to home.

Mina Kim:

So when you say it’s a response to demographic shifts, you mean that the content of the books that you’re seeing really targeted for banning at this point are books that center basically marginalized groups.

Suzanne Nossel:

I mean, overwhelmingly that’s the case. The Maus incident got so much attention because so venerated, and for good reason, but the overwhelming bulk of the books that are being targeted in these bans are books by and about authors and characters of color or LGBTQ, transgender in some cases. So, books that reflect this evolution in our demographic, that bring forward stories that have not been told, identities that haven’t been fully recognized or embraced.

Suzanne Nossel:

There’s a second related piece, which are narratives that are more critical about American society, that talk more about the role of slavery. And a lot of this was energized by the pushback against New York Times’ 1619 Project, and its effort to elevate the place of slavery throughout American history and through the present day. And some historians dispute it vigorously, but the idea that should be banned, and that was the subject matter of a lot of the initial curriculum bans that we saw introduced in state houses last year; that that narrative has to be suppressed, that that account of American history if it is credited is going to run counter to the belief systems, the political power that is held by a certain group.

Mina Kim:

Well, Paul writes, “Someone needs to remind these “conservatives” that they’re against cancel culture and censorship. And if they’re truly in favor of “freedom”, they should not be denying the right to read to those parents who want their kids to do so. If they want to tell their own kids to avoid some titles, they should do so, and let other parents make their own decisions.”

Mina Kim:

Let me go to caller Colin, in San Francisco. Hi, Colin.

Colin:

Good morning. I disapprove of book bans, but I also feel that Maus is actually not age appropriate material for school children. And particularly the way that the graphic novel, Jews are portrayed as mice, the Germans as cats, and then the Polish characters are all portrayed as pigs. And to me, I think that dehumanizes a whole class of people and also ignores that, yes, there were Polish people who persecuted Jews during the second World War, and then there were also others who sheltered Jews at the risk of their own lives. And I don’t think school children have the context to understand what a complicated time that was, and in the cartoon format to just portray a whole nationality is a species of animal…

Mina Kim:

Colin, do you mind if I, not to put you on the spot…

Colin:

I just don’t think that’s appropriate for school children.

Mina Kim:

Yeah. I’m just curious if you think the book should be banned from school library shelves and school curriculum, like actually banned.

Colin:

I don’t feel that it’s appropriate for children even at the… Perhaps at the level of sixth grade and higher, it could be accessible. There’s a lot of other dark stuff in the graphic novel too, like mass suicide, that I feel for school children that’s really difficult thing to process.

Mina Kim:

Thanks Colin. Viet Thanh Nguyen, do you have a reaction to what Colin is saying as well? Just as a parent of a school-aged child? The ban, I believe with Maus was in eighth grade curriculum in Tennessee.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Eighth grade curriculum. Well, that would be what about 13, possibly 14 years old? Honestly, I think children at that age are really capable of dealing with a lot. I may not be the best example of this. Like I said, I became a writer because of my exposure to things that I probably shouldn’t have been reading according to some parents at that age, but I read some difficult things at that age, not just Larry Heinemann’s Close Quarters, but for example, I read Voltaire’s Candide when I was around that age. I read All Quiet on the Western Front.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I don’t think that being exposed to these kinds of things is irreparably damaging to children. And again, I think that what’s really happening is parents are afraid of having the conversations with their children. Why, in this case with Maus, for example, does the artist decide to use animals to represent particular kinds of peoples? That’s a great question to have, and I think that a 13 or 14 year old child or student, young person, would have an incredible conversation with their parents or with their peers exactly around that kind of issue. And then all kinds of magical things can unfold at that point around the question of both history, but also around the question of art and artistic decisions. So, I’m actually in strong disagreement with our caller on this one.

Mina Kim:

Well, Tony writes, “I imagine that now Maus has been banned, every eighth grader will find a way to read it.” We’re talking with Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, professor at USC in English and Comparative Literature. Also, Suzanne Nossel is with us, CEO of PEN America. And after the break, we’ll actually meet an author who has written a book that was recently banned. So, stay with us for that. We’re talking about book bans that are sweeping the country at the moment with great intensity and learning more about the origins and motivations. We’ll have more after the break. Stay with us. This is Forum, I’m Mina Kim.

Speaker 2:

Support for this podcast comes from Sutter Health, dedicated to making healthcare accessible. From same day appointments to virtual visits, the Sutter network strives to provide patients with whatever treatment they need, always. More at SutterHealth.org.

Mina Kim:

Welcome back to Forum, I’m Mina Kim. We’re talking about the recent wave of book bans, a trend which the American Library Association has called unprecedented. You, our listeners, are with us; giving us your questions, your reactions. If there’s a book that you are reading that’s been banned, what’s been your reaction to that? What are your thoughts or questions about what’s going on with regard to books in this country, and what larger issues that it’s trying to address?

Mina Kim:

(866) 733-6786 is the number to join the conversation. (866) 733-6786. Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram is where you can post thoughts online at KQED Forum. You can email us, forum@KQED.org. And joining me now is Ashley Hope Pérez, an author and writer of the book Out of Darkness. It’s a young adult novel. That’s been banned by a Texas school district and placed on lists of books to be banned. Ashley Hope Pérez is also an associate professor of comparative literature at Ohio State University, and a former high school English teacher. Thanks so much for being with us.

Ashley Hope Pérez:

It’s my pleasure.

Mina Kim:

First, can you tell us what your book is about, Out of Darkness?

Ashley Hope Pérez:

Yeah. Out of darkness is a historical novel that tells the story of a young woman, a young Latina from San Antonio and a Black American boy in East Texas, and it’s a love story that takes the 1937 New London School Explosion as a backdrop. So, it certainly delves into challenging themes that readers are put on notice of the minute they open to the first page, which takes them to the aftermath of this explosion. So, you’re seeing the bodies of children right there at the start. And one of the reasons that I frame the book the way that I do is so that readers have a sense from the beginning of what the thematic intensity of it is.

Mina Kim:

What have the attacks against the book then been like, what have they been saying about Out of Darkness?

Ashley Hope Pérez:

I mean, I’ve been called pedophile, a groomer, all the things. I’m a survivor of sexual trauma, and so those kinds of remarks are really hurtful. But at the end of the day, especially as a former teacher myself, I’m just aware of who this harms and it is… I became an author of young adult fiction because of my students, and in large part because of how little representation there was for them in our high school library. So, the notion that after this hard won diversification of the stories that are available to young people being rolled back by parents who are not concerned about what their own child is reading, but actually want to restrict what other kids are reading, and more importantly, want to signal who’s in control and whose stories matter. And I think that what affects me most about these attacks, aside from the ugly messages and phone calls that I get, is simply the harm that they do to the people who should be at the center of decision making in schools, and that’s the students.

Mina Kim:

How did you find out your book was banned?

Ashley Hope Pérez:

Well, the wonderful PEN America folks let me know about the first ban, and has since been banned in, gosh, about six or seven places and put on review in many, many other places. So, now it’s almost an ordinary thing to open my email and see, for example, this morning it was removed in Georgia in the school district. So, I just take on the news and do my thing of trying to signal what parents who want young people to have access to diverse literature can do.

Ashley Hope Pérez:

But I do want to speak just briefly if I could to the point earlier about the notion that, “Well, young people can find these books. Maybe it makes them more enticing.” And the fact is that for some students, the school library is the point of access to books. I had students when I was teaching in Houston, Texas who worked 30 hours outside of the school day, who were caregivers, who were parents. Some kids didn’t have bus fare to the public library, and the school library was the place for them. So, that school library needs to have the books that meet their needs.

Mina Kim:

I’m going to go to some calls that were coming in, inspired by what you’re saying, Ashley. Meera in Berkeley, thanks for calling. What would you like to share?

Meera Sriram:

Hi. Thanks for bringing up this discussion on KQED. So, I’m a children’s author. I write picture books for children, young children, and I had a picture book called Between Two Worlds: The Art & Life of Amrita Sher-Gil come out last year in fall, and the book is a biography, the life story of a very underappreciated artist, a biracial artist, Amrita Sher-Girl.

Meera Sriram:

And it was sad to see that one day, my editor actually emailed me saying that an organization that collaborates and curates with school libraries decided to drop a huge purchase of copies of her book because some of the librarians were afraid of parent backlash in response to image in one of the spreads in the picture book, which depicts a naked woman.

Meera Sriram:

I was really surprised. I’m like, “Where’s is the naked woman in the book? I don’t even know.” And I was frustrated in the beginning. And then I realized, the image that they were talking about is actually a cave painting, a second century cave painting of the Ajanta Ellora Caves in India that was a huge inspiration for the artist. So, there’s a spread that shows the artist wandering around the caves and how that inspired her future paintings. And I just wanted to bring this up and say that technically my book was not banned, but just how the close mindedness and ignorance of gatekeepers and adults are coming in the way of children learning about this phenomenal early 20th century artist. So, yeah, I just wanted to share that. Thank you.

Mina Kim:

Sorry that happened to you, Meera, and thanks for sharing your experience. With regard to children, Kate writes, “In all the articles and conversations about the current rash of book bannings, there is a glaring omission; the voices of the students. I wish we could hear from the middle and high school students in the communities where these uninformed adults are making these decisions, especially the queer students and the students of color whose identities are being targeted and suppressed. Also, shout out to San Jose Public Libraries. Like Mr. Nguyen, that’s where I did some of my most formative and radical childhood reading.”

Mina Kim:

Viet Thanh Nguyen, you said you noticed that your son noticed these book bans as well. What has his reaction been to that or his questions and concerns around it?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Oh, no, actually my son has not noticed.

Mina Kim:

Oh, I’m sorry. I thought you meant people are opening social media and reading it, but maybe it’s not your child. But I don’t know if you have any thoughts on student voices as a professor?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

I think the student voices are absolutely critical. And again, I think so many parents underestimate the students. I mean, I work with college age populations, but there’s parallel issues here where students will come sometimes talk to me about the things that they can’t talk about with their parents for whatever reason.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

And of course, we’re living in an age where parents, some parents and some politicians, are freaking out about what’s in the library, for example. And yet, they allow their children to have iPhones or whatever. I’m much more worried about what my son has access to on the iPad that I give him access to for 30 minutes a day.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

There is a reason to curate and to be concerned, but I don’t think books are the most dangerous types of media that our children have access to. So again, it goes back to the question of moral panic. It goes to the question of scapegoating certain kinds of things as an excuse for dealing with other kinds of social, political, personal issues. Again, I think the telling sign books in particular that are being targeted versus other kinds of media.

Mina Kim:

Ashley Hope Pérez, have you heard from students? As you were mentioning earlier, for some, the school library is their only point of access?

Ashley Hope Pérez:

Oh, absolutely, and yes. I mean, I’ve had the privilege of speaking with some students and coordinating with some banned book clubs. I mean, students are livid, right? This is such a patronizing and frankly insulting stance to take. I think that the message I hear from students over and over is that this is what our lives contain; challenge, difficulty. This is not something that we’re only going to encounter in the pages of book. And I think that what students want are spaces to grapple with difficult issues, not spaces where they’re denied access to those difficult issues.

Ashley Hope Pérez:

Another message I hear from students is that they would like to see these parents, rather than being distressed about a book that depicts racism, be distressed about racism out in the world and do something about that. I think that that’s really a core problem in these attacks on books is that the parents are reacting to the books in the ways that we wish they would react to those problems in the world; sexual abuse, rape, all the kinds forms of harm that young adult authors and other authors strive to grapple with as the human experiences that they are.

Mina Kim:

And Suzanne Nossel, you have been hearing about students mobilizing against these book bans, right?

Suzanne Nossel:

Yes. We’ve been working with students. We held a teach in December to equip students to push back. We’ve got resources on our website to enable students to make the arguments, and they’re some of the most effective spokespeople. In Newark, Pennsylvania, it was really the students who got a very comprehensive ban turned around through their activism, and this is a real opportunity. The rising generation sometimes its very skeptical of principles of free speech. They see it as a smoke screen for hatred. They’re very concerned, rightly, about bigotry and bias and stereotyping and free speech sometimes seems like it just protects all of that.

Suzanne Nossel:

And so, I think these issues can galvanize the new generation. We do free speech institutes for young people to teach them about what’s at stake, even if you might agree with the ban of a certain book. Say, like the caller, you don’t think Art Spiegelman’s Maus is appropriate for a seventh grade career curriculum, but what’s going to be banned next, and who’s got the power to decide, and do we want politicians and school boards overriding the judgment of teachers and librarians about what should be on the shelf?

Suzanne Nossel:

And so, this is a real opportunity, I think, to engage a rising generation about the stake that they have in free discourse, freedom of the thought, and of free society.

Mina Kim:

We’re talking with Suzanne Nossel, CEO of PEN America, Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of the Pulitzer Prize winning book The Sympathizer, Elizabeth Harris has joined us earlier, is a reporter for the New York times covers books and publishing for the newspaper. Ashley Hope Pérez is with us, author of Out of Darkness, a young adult novel that has been banned and is on a list of books to be banned in different states across the country, and you are listening to Forum. I’m Mina Kim.

Mina Kim:

Let me go to a few more calls. Ian in Santa Cruz joins us. Hi, Ian. Thanks for waiting.

Ian:

Hi, thank you so much. So, I just want to support what Suzanne just said about a free society. I grew up in South Africa under apartheid, and I remember when the police came to my parents home to look for books. We weren’t allowed to read.

Ian:

When I was 17, I bought a James Baldwin book. They searched my suitcase at the airport because I’d been in Zimbabwe, in those days Rhodesia, and I was strip searched and they found this book. I didn’t go to prison because I was white and because my parents knew people, but that was the society we grew up in, and that’s the society that we are embracing when we start down this path of banning books, because banning books is just the beginning of the authoritarian repression and control.

Ian:

And I would submit that kids that are reading the newspaper or watching TV and seeing the the George Floyd tape over and over again, and listening to the ex-President talking about racist prosecutors who are People of Color and all of that; if you’re going to ban books, they’re being exposed to that. That is much worse. That’s like listening to the speeches that were given by the dictators in the 1930s in Europe and people were being exposed to that.

Ian:

So, I think that the discourse that Suzanne is advocating, it’s about time that we started getting more bold in the society to prevent this indication of what can come. And if we’re not careful, we are going to land up where South Africa was in the 1960s, and it’s a horrible place to be.

Mina Kim:

Yeah. Ian, thank you for sharing that experience. Suzanne Nossel?

Suzanne Nossel:

Yeah. Just to say, I really appreciate that comment. Here at PEN America, we do a great deal of work on free expression issues around the world, pushing back against the repression of press freedom, book bans, the arrests of writers and poets and countries across the world. And so to see these trends in our own country and this borrowing from the authoritarian playbook that the caller speaks about is really disturbing.

Suzanne Nossel:

Tactics like in Virginia, the creation of a tip line urging parents to call a hotline and report on teachers and educators who may be pushing ideas that are considered suspect; that’s right out of the Stasi in East Germany during the Cold War.

Suzanne Nossel:

Particularly free speech has been an issue in this country that at its best incarnation has risen above politics, and there have been impassioned defenders of free speech on the left and on the right. This is something to me that we need to come together on. Even if there are people who think, “Well, the censoriousness on the left has gone too far, and so we’re justified by pushing back in these ways because they’re trying to ram forward certain new ideas that we reject or orthodox ideologies.” But these measures, I think by any criteria, are just at odds with the freedom of thought and the first amendment protections that we treasure. And so, I think we’ve got to wake up and see that and recognize where this could lead and activate within communities to stop it now.

Mina Kim:

Ashley Hope Pérez, do you have ideas for our strategies to stop this trend?

Ashley Hope Pérez:

I think really helping students organize, and not be stop from reading by these removals. I’ve been working with teachers to find creative ways to make books that are being removed visible. So, they can’t have the book in their classroom, but some art teachers have been making these miniature books that they can make a display of, and then students ask about them and they can get information about where else they can find them. I would love to see someone organize a way to connect people who want to donate money for books with students in the communities who want a book that’s been banned, but can’t get it another way, so that we can make those connections.

Ashley Hope Pérez:

But I think that the student voices, for example, in school board meetings are incredibly powerful and effective, and I hope that adults who care about their young people being prepared for the century that they actually live in will encourage them to speak about what these books mean to them and what their removal means to them. Because when parents show up to school board meetings calling books that are about queer kids filth, or books that are about Black and Latinx kids garbage; they are signaling something to students who share those identities, and they are signaling that they don’t belong, that they’re not welcome; and that is an incredibly painful message to hear from your neighbors.

Mina Kim:

Viet Thanh Nguyen, last comment from you about the impact of this trend not being stopped or reverse soon in your mind?

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

Well, I would reinforce what Ashley said, that the students have a lot of power today. Young people especially. This is the age of digital media. They could organize not just in person but online. So for example, when I get requests from high school students saying, “Hey, we love your book. Our class is reading it. Will you come and talk to us?” I say yes, because I think it’s an incredible opportunity to speak to young people as an author, and it’s very easy to do on Zoom. So, young people out there, organize, do Zoom events, ask your favorite author, ask the author you’re curious about to come and speak to you, promise that you’ll read their books; and I think a lot of authors will respond. If parents and school boards aren’t willing to have the dialogues, the students themselves can initiate those dialogues.

Mina Kim:

Viet Thanh Nguyen, Suzanne Nossel, Ashley Hope Pérez, thanks to all of you for talking with us today about book bans, and thanks to our listeners for their thoughts and experiences. You’ve been listening to Forum. I’m Mina Kim.