Michael Upchurch reviews The Committed for the Seattle Times.

Few novels have catapulted their way into the American literary canon as quickly as Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning debut, “The Sympathizer.” Its place there seems as assured as Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” or Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22” — books whose disorienting absurdities it echoes.

Narrated by the bastard son of a French priest and a teenage Vietnamese housemaid, it’s a tale of masked identity and marathon subterfuge. Its nameless protagonist, a communist spy embedded in the South Vietnamese military, suffers from what he calls a “weakness for sympathizing.” He’s a shrewd actor who’s been playing a role for so many years that he’s no longer certain who he is.

Such was the power of “The Sympathizer” that the news of a sequel to it may excite two reactions. One is: “Can’t wait!” The other: “Is that really a good idea?”

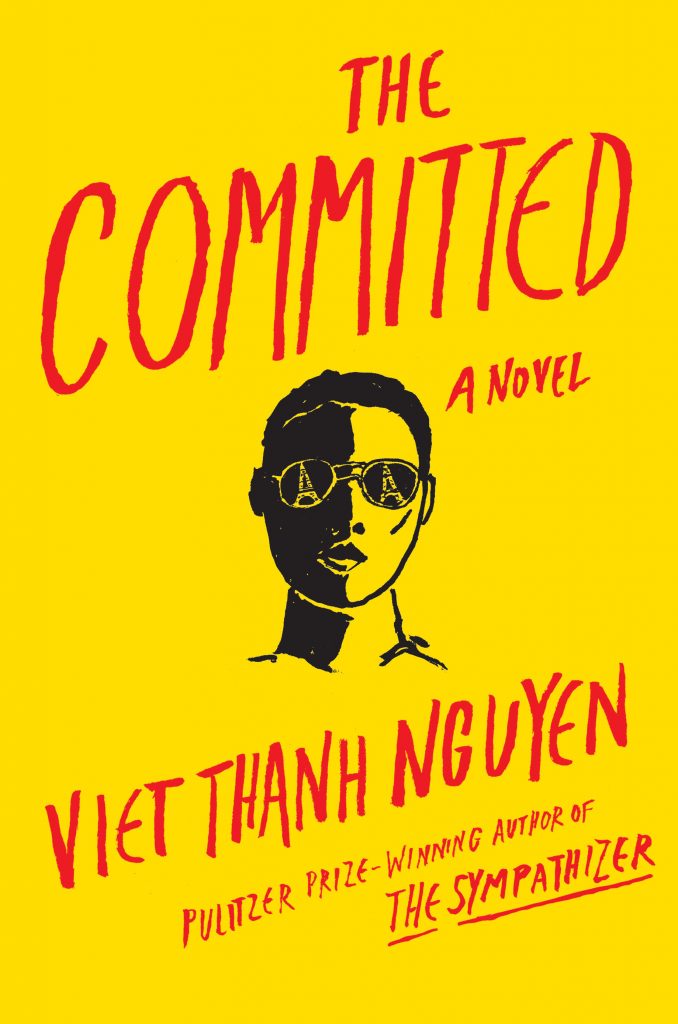

“The Committed” (the title is a pun on both allegiance to a belief and institutionalization in a psychiatric asylum) takes place in Paris six years after the ordeals that Nguyen’s anti-hero underwent in “The Sympathizer.” It contains brilliant writing, perverse insights and Tarantino-esque action sequences. Its wit is bitter; its pain is palpable. But it’s also less fluid in feel than “The Sympathizer,” as though its narrator — rather than being a fully animated and unpredictable character — is now a useful construct on which Nguyen can hang intellectual concepts.

As “The Committed” opens, Nguyen’s narrator is “dead” in some sense. He has, he says, “two holes in my head from which leaks the black ink in which I am writing these words.” After intense tortures in a Viet Cong reeducation camp (chronicled in “The Sympathizer”) and two years in a refugee camp in Indonesia, he and his lifelong friend Bon have wangled their way to Paris, where they fall in with a Vietnamese expatriate community whose mix of political persuasions — Francophiles, armchair communists, anti-Viet Cong militants — makes a mockery of the lethal conflict in their homeland.

Nguyen’s narrator has acquired a passport name, Vo Danh. At the same time, his identity and beliefs have been shattered. He’s subject to “unexpected bouts of blubbering” and is continually visited by the ghosts of those he’s killed. He’s clearly cracking up. Still, he has to make a living.

His solution is to go from his “dubious profession as a spy” to an “even more dubious apprenticeship as a gangster.” He and Bon become drug dealers, and it isn’t long before Vo Danh develops a drug habit himself. In this addled state, he repeatedly confronts existential questions.

“For most of my life,” he reflects, “I had constantly and desperately believed in something, only to discover that at the heart of that something was nothing. So why not give nothing a chance?”

Though he feels empowered by the “nothing” he has embraced, his cynicism, especially concerning human connection, is complete. Wedding rings, he quips, are “the most meaningless symbol in the world.” Cuddling, he adds, is the “most unnatural and shocking of sexual positions.”

Throw in some good old-fashioned sexism (“did two women talking to each other without a man present make any sound?”) and scorched-earth atheism (religion’s promise of an afterlife is pure “marketing genius”), and you have a character with few viable paths or exits before him.

Nguyen leavens his narrator’s grim outlook some scathing humor, whether it’s Vo Danh’s mystification as to the appeal of French rock star Johnny Halliday (“a taste the rest of the world could not acquire”) or one of his drug-dealing colleague’s comments on the dimwitted crew he’s joined. “‘Nuance’ is not in their vocabulary,” the fellow says. “Hell, ‘vocabulary’ is not in their vocabulary.”

There’s a mordant appeal to these proceedings, and the writing can be brilliant. Still, gangsters, drug deals, femmes fatales and shootouts aren’t always as interesting as the divided sympathies and warring convictions that powered Nguyen’s remarkable debut.

Many readers will likely agree with book’s indictment of colonialism’s legacy. “One can get away with mass murder and wholesale looting of countries and continents,” Vo Danh reflects, “if one handles oneself with a splash of élan, a dash of finesse, and gallons of hypocrisy and selective amnesia.” But that doesn’t mean “The Committed” has the same power to surprise that “The Sympathizer” did.

One telling moment as to what’s amiss comes when Vo Danh responds to a description of his French priest father as “a colonizer and pedophile.”

“When you talk about me like that,” he wryly laments, “I feel like a symbol.”

What the reader is left with is a convincing, if overstated, vision of a “broken world” where “the problem was violence and the solution was violence.” It’s a worthy read, even it falls short of the impact of its predecessor. Newcomers to Nguyen should also be aware that, as hard as Nguyen works to backfill details, they’ll need to read the first book to grasp what’s at stake in the second.