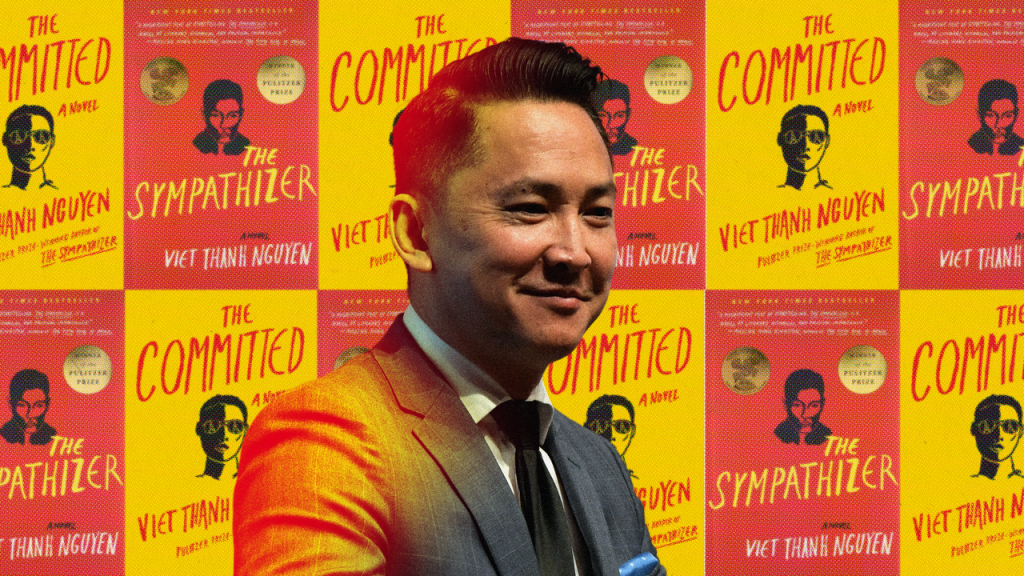

Viet Thanh Nguyen talks about creating a “James Bond” figure and more in this interview with Jean Chen Ho for GQ.

In March of this year, the fiction writer and cultural critic Viet Thanh Nguyen published The Committed, the highly anticipated sequel to The Sympathizer, his Pulitzer Prize–winning first novel. In Nguyen’s latest, readers encounter anew the half-Vietnamese, half-French former spy who now finds himself in Paris, reeling from the aftermath of his Communist reeducation. The year is 1981, and Vo Danh—still “a man of two faces and two minds,” if no longer a double-agent and political subversive—falls in with a local Chinese syndicate, for whose protection and affiliation he begins to sell hashish. The Committed is written in much of the same exuberantly heady, self-conscious style of satire that delighted fans of The Sympathizer, with perhaps even more punchlines (and unabashed punning) per page, efficiently delivered alongside post-structuralist feminist theory and Marxist critique. Beyond the slapstick and toilet humor, however, profundities of emotional consequence emerge: the earnest adolescent boy who masturbates with a squid carcass recalled in The Sympathizer has grown up into a man whose erections fail to appear—“a war wound,” he demurs—when anguished memories of a sexual violation resurface.

Nguyen is a University Professor at USC, where he teaches across three academic departments: English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature. Besides the two novels, he is also the author of The Refugees, a short story collection, and two monographs of literary theory and criticism—Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, and Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America. For all of his literary success, Nguyen has become the de facto public intellectual to read—and for many, to debate and flame, on Twitter—when it comes to Asian American identity discourse. “I’m a professional Vietnamese American now,” he quipped good-naturedly, when we spoke via Zoom on April 20th.

GQ: One of the many contradictions the narrator of The Committed deals with is the difference in theory versus lived experience. When he meets these high-minded, if a bit self-aggrandizing, Marxist intellectuals in Paris, he’s prompted to ask: have you ever actually lived through a revolution, do you know what that’s like? What is it about this tension that interests you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: My whole life had been shaped by these distinctions, because that’s what led to the war in Vietnam, and me becoming a refugee. And of course, I’m writing as an academic who’s only analyzed these social forces. I did live through a revolution, but I’m not sure it counts if you’re four years old. Those questions have preoccupied me, ever since college—the difference between theorizing a revolution and living a revolution.

Throughout both novels, I’m constantly trying to figure out how to combine the serious and the satirical. The idea being that the satire will help the serious stuff go down more easily. You can have a very serious conversation between two people on a revolution, the theory versus the practice, and we do that all the time in academia. In this case, however, if the whole novel was characters having these conversations, that would be a bit dry. So, I had to figure out how to spin the conversation, throw some laughs in. My task as a satirical novelist is to find the comedy that’s always present in human contradiction.

Colonization is what’s happening in the United States, it’s arguably what drives the US to do what it does, both domestically and abroad. To me it’s a word that gives shape and connection to the many different kinds of problems happening that are interconnected, which I think many people would like to say are not connected.

I’m thinking about what you just said, using humor to make the theory go down easier. One of the ways you do this in The Committed is around what it means to be a woman and an intellectual; the intersection of gender, in particular, with race and class. In the novel, the narrator begins to contemplate his relationships with women in a way that challenges his previous views, and actions, from The Sympathizer. What animated your thinking around these conversations he has with his aunt, and on his reflections with regards to sex and women?

[The Sympathizer] is a novel told from the perspective of a man who enjoys women. In writing the novel, I discovered that I was maybe enjoying it too much—I myself was implicated in the pleasure of his gaze, his treatment of women. So I felt that part of what The Committed had to do was to pick up on this thread that’s fundamental to the narrator’s life, and mine too—heterosexual men’s attitude toward women, and how deeply it’s tied to a certain kind of masculinity. We would call it “toxic masculinity” now, in which a lot of men participate either explicitly or vicariously. It saturates so much of our lives. I wanted to take that on in The Committed.

But the narrator couldn’t just suddenly become a feminist. That’s not realistic. That would’ve been me, the professor, stepping in and saying, this is the “logical” response: feminism! So given the constraints I had set up—that it’s first-person, seen from his point of view—he would be challenged by people who were feminists, such as his aunt, and that we would see the limits of his own vision, even as he’s struggling to try to understand what his problems are around his sexuality, his masculinity.

I want to go back and ask you about how you said you were enjoying the sexual elements of writing The Sympathizer a little “too much.” One of the pleasures of reading The Sympathizer, and The Committed, is that the narrator has a lot of fun. He’s a heterosexual Asian man who enjoys women, and we’re allowed to judge him for that as readers, but there’s also a lot of joy in reading this character and all the trouble he gets into. It’s not often that we see this kind of literary figure.

That was very deliberate, to create a character who could be “James Bond”—albeit a bad James Bond—but a James Bond figure. Why can’t Asian men do this kind of thing? Hopefully it was fun for readers. It was fun for me. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be criticized. The narrator is wracked by contradictions. Yes, sex is great. Sex is fun, if both parties are consenting. And yet the underlying fact is that it’s impossible to separate consensual pleasure from other components of violation and misogyny. He had to confront the rape that took place [at the end of The Sympathizer]—it’s part of the same system in which his pleasure is embedded.

You write in many different rhetorical modes. You’re a professor and a fiction writer, you write op-eds, you make political commentary. As a public thinker, how do you make sure that your work continues to describe what’s true in this specific historical moment, but continues to generate a politics for a future that you’d like to see?

When we see repetitions—repetitions of anti-Asian violence, repetitions of American warfare in foreign countries, repetitions of Black people being killed by police—what we’re seeing is repetitions of systemic, structural violence and exploitation. I’ve been searching for a language, a method, for how to deal with these things, since I was in college and became an “Asian American.” Writing and engaging with these ideas in different forms has allowed me to refine my thinking about these systemic issues, these repetitions and cycles. To give it a name, which for me is “colonization.”

In The Committed, there’s a lot of emphasis put on colonization, because it’s what happened in Vietnam. Colonization is what’s happening in the United States, it’s arguably what drives the US to do what it does, both domestically and abroad. To me it’s a word that gives shape and connection to the many different kinds of problems happening that are interconnected, which I think many people would like to say are not connected. That’s part of the divide-and-conquer strategy of colonization, to say: “your group is here, your group is there, you have different issues. Anti-Asian violence is not related to anti-Black violence, and neither of these things is related to warfare overseas.” When in fact, in my mind, they are connected.

You write a novel, you reach a certain kind of person. It’s one thing to give a lecture to a university audience, which is a friendly audience, for the most part. It’s another thing to go to West Point, or now, weirdly enough, I get invitations from corporations to give talks. I wrestle with that. On the university lecture circuit, you’re talking to people who generally tend to belong in your world view. But isn’t it just as important to talk to a West Point audience, or to different corporations, because they are really the ones who need to hear me say, “We’re living in an age of colonization”? I’m still trying to figure it out, how to perform to different audiences as a part of this political work.

So how do you shift when you talk to someone at West Point? Or to people who work at a big corporation?

I try not to change the message. I have to adjust a little, to the audience. So at West Point, for example, I started off with a “Go Army, beat Navy” joke. I was told to do that by a West Point alum, and it worked, there was applause. So you make certain concessions to the audience. But at West Point, I said: “America is a beautiful country and a brutal country.” The culmination of the lecture was, “You’re all ‘patriots’ here. But we need to recognize that this is a country born out of genocide, slavery, and colonization.”

I try not to shift the message for the audience, but I do try to change the parameters of jokes, or the narrative. They can agree or disagree.

What’s your writing routine?

I’m not a writer who writes every day, but my strategy is to always have multiple projects. The moment I’m done with a novel, I’m ready to start the next novel. When I’m done teaching this semester, I’ll be working on this nonfiction book. And when I’m done with that, hopefully by the end of the summer, I have tons of notes for the third installment of The Sympathizer trilogy. So I’ll get to that right away. I don’t know what other writers do, but when I finish something, I’ll celebrate for a day, then I’ll go right back to writing. There’s always a project.

Can you talk a little about the nonfiction book project?

I just had an interesting conversation with Lee Isaac Chung, the director of Minari. He said that he’d done other movies before, but Minari is his most personal. It’s his only autobiographical film. He said that for a long time, he didn’t want to do autobiography, because it didn’t seem very interesting, life growing up in rural Arkansas. And then he ends up making this incredibly powerful movie. I feel the same way. I grew up well into adulthood thinking I had a boring life. Who wants to hear about my life? I don’t. And then I wrote an autobiographical story in [the short story collection] The Refugees. It was very hard to write. And now, there’s a lot of my life in these op-eds, in the speeches I give. I’ve turned my life into a narrative as a vehicle for delivering these messages about colonization. So I think the momentum of all that has pushed me into writing this nonfiction book, which is only partly a memoir, and a lot of it is politics, and cultural critique.

For much of my life, I thought my life was boring, probably as a way of normalizing and coping with the elements that were particularly difficult. A lot of refugees I know, we just contain it, like: “Yeah, that happened,” and you just go on. But as a writer, you recognize that you need to go there. Everything that I’ve denied has been emotionally powerful for me, it’s compelled me to be a writer and an academic.

It was just announced that The Sympathizer will be adapted into a TV series, directed by Park Chan-wook. Are you writing the adaptation? What’s your role in the creative process?

When I first came to USC, I had a colleague in the Classics department who sold a screenplay, about the Greek gods. So I also thought, I can do that. I wrote the screenplay, and it sucked. It was so bad. But it taught me two things. One, I read a screenplay writing manual and I learned plotting, which I still use constantly. The other thing it taught me is that I don’t want to write screenplays. I’m just focused on writing novels now. So I’m not writing the adaptation for the series. But I am getting an executive producer credit, which I think I deserve because I’ve attended so many meetings and talked to so many people, trying to make this happen!

Last question, which you can decline to answer…but it just so happens to be 4/20 today, and the narrator in The Committed sells and smokes hashish. Are you celebrating the holiday?

Well, thank you for reminding me! The drug deals and hashish scenes in The Committed are certainly based on things I’ve witnessed…and now of course in California, marijuana is legal. In fact, you can have it delivered to your door like pizza. I think I have some, high up in a kitchen cabinet, but it’s probably more than a year old. Who knows if it’s still any good? With kids, teaching, and writing novels, who has time? I’m too busy to get high. I guess some writers can work when they’re high or drunk. I can’t do it!