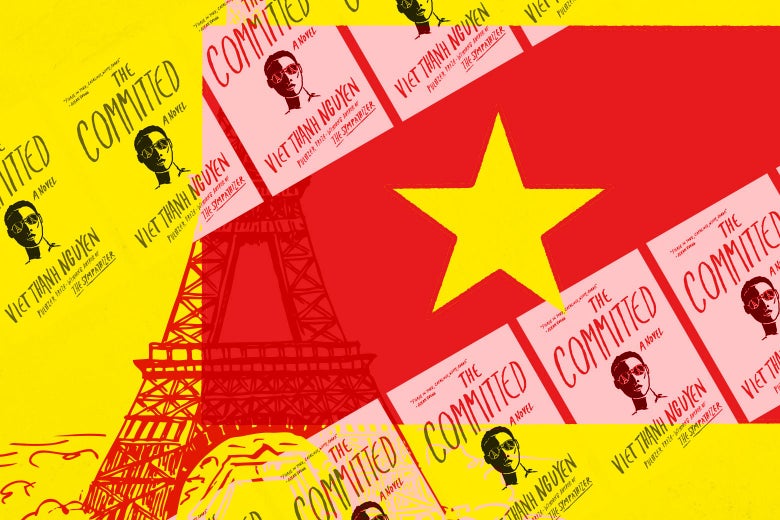

Laura Miller reviews The Committed for SLATE.

The last time readers saw the nameless narrator of The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s 2015 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, he had survived a psychically obliterating reeducation at the hands of the communist regime he had long served as a spy and was packed into a boat full of refugees, headed toward fresh hells. In The Committed, Nguyen’s new novel, he finally washes up in France in the 1980s. There’s a deliciously complex irony to this development, as there is in so much of Nguyen’s fiction. The Sympathizer, as Philip Caputo noted in his review for the New York Times, is one of only a handful of American novels about the Vietnam War and its aftermath that puts Vietnamese characters at center stage. With The Committed, Nguyen takes those Vietnamese to the dark heart of their postcolonial turmoil—and at the same time again denies Americans the spotlight we so love to hog. America simply isn’t where the action is. The American Dream, the narrator opines, is “as shallow, boring, and sentimental as a bad television show that had somehow become a hit.” But oh, France!

Powerfully influenced by the equally anonymous narrator of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Nguyen’s narrator (sometimes referred to as “the Captain” in The Sympathizer for his rank in the South Vietnamese army) now considers himself fractured into at least three parts. Before, he was just two, as a result of being the illegitimate son of a Vietnamese orphan and a Catholic priest. The epithet that most rankles him, “bastard,” has, in his eyes at least, less to do with his unwed parents than with his biracial identity. He feels accepted nowhere, and near the end of The Sympathizer he is sent off to almost certain death by the South Vietnamese general he has attended to so faithfully (and lethally) as an aide. At the airport, he finds out why. “How could you ever believe we would allow our daughter to be with someone of your kind?” the General asks him.What could be more French than a gangster novel of ideas?

Of course, the General does not know that his faithful deputy has, in addition to canoodling with his daughter, been regularly reporting on his counterrevolutionary activities via coded letters to an “aunt” in Paris. In The Committed, it is this woman the Captain stays with when he first arrives in the City of Light. The chicly assimilated Vietnamese “aunt” explains that it’s possible to become French, “but you must want to be French. You must look in the mirror and see a French person, not an Asian person or some other color.” For her, a book editor, this takes the form of smoking, fashionable radicalism, and casual affairs with an assortment of fatuous leftist intellectuals (including one known by the initials BFD, an evident and very funny parody of the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy, who goes by BHL).

The Captain no longer considers himself a communist, not after his Orwellian reeducation back in Vietnam: sensory and sleep deprivation at the hands of a commissar without a face, a man so disfigured by a napalm attack that he is unrecognizable as Man, the Captain’s former boyhood friend. Subjecting the Captain to this brutal ordeal to purge him of his faith in the revolution, Man leaves the narrator believing in nothing—that is, in a grammatical and ontological brain twister: that nothing is not only something, but it is the only thing worth believing in. This detached viewpoint belongs to his third self. “You may think that I am being a nihilist,” the Captain further explains, “but you could not be more wrong. While nihilists thought life was meaningless and rejected all religious and moral principles, I still believed in the principle of revolution.”

What exactly this means, and how it’s possible to live by such a philosophy while psychologically fractured, is the subject of The Committed. The Captain gets a job in “the worst Asian restaurant in Paris,” a front used by a gangster known only as the Boss, a Vietnamese of Chinese descent. The Captain pitches his “aunt’s” friends to the Boss as a potentially lucrative market, and in no time he’s selling drugs to professors and politicians. This he considers a downfall, not because of the drugs, but because he worries he’s “becoming a capitalist, which is a matter of bad morals, especially as the capitalist, unlike the drug dealer, would never recognize his bad morality, or at least admit to it.” This work leads him into violent encounters with a rival French–Algerian gang and a convalescence in a brothel where the Senegalese bodyguard reads Frantz Fanon and watches intellectual talk shows all day. The Captain serves drinks at an event much like the grotesque racist orgy in Invisible Man, but in this version, the Boss has cameras hidden everywhere, collecting blackmail material on Paris’ white elite.

None of this, you may notice, sounds like the behavior of someone who believes in the principle of revolution. The Captain’s dilemma is that he both loves and hates the French, his nation’s (and the Algerians’ and the Senegalese’s) colonizers. They are so charming, and they are such tyrants. So many of the concepts he has taken up in order to dismantle their power—from Marx and Althusser to Julia Kristeva—come from the same European cultures that created the colonialism that brutalized Vietnam. The French Catholic priest who never acknowledged his paternity was also the benefactor who saved his mother’s life during the Japanese-imposed famine of World War II. Also, the French make such excellent baguettes, and the Captain is very fond of cognac. Finally, what could be more French than a gangster novel of ideas?

In The Sympathizer, the Captain’s great skill and abiding shortcoming was right there in the book’s title: his ability to sympathize with both sides in the Vietnamese civil war. This makes him much like a novelist, who must fully imagine the interior lives of his characters, even the villains. In The Committed, the Captain similarly disappoints everyone by refusing to sign on unreservedly to any enterprise: France, Vietnam, organized crime. Even his allegiance to revolution seems dubious, despite his protestations—for what is he doing to further the overthrow of the existing order? His devotion is, in truth, entirely personal. Throughout both novels, the Captain’s decisions are driven by a desire to protect his best friend Bon, to whom he swore a blood oath as a boy. But Bon, who accompanies the Captain to France and who lost his father, wife, and son to the North Vietnamese, wants nothing more in life than to kill communists, having no idea that his friend secretly was one.

Absolutism is always reductive, and therefore, like the inability to sympathize with one’s enemies, is an anathema to art. While the Captain has a bit of a feminist awakening in The Committed, he is mostly a cynic, and he has been ever since The Sympathizer. This is the heart of his charm, which in this reader’s opinion is more potent than that of the French. I could never entirely believe the Captain as an ardent communist, and in The Committed, he is free to let his sardonic flag fly. He’s at his funniest when pointing out the absurdities around him, such as a “culture show” designed to celebrate Vietnamese traditions, “even if staging a culture show was really an acknowledgement of one’s cultural inferiority. The truly powerful rarely need to put on a show, since their culture was always everywhere.” To the Captain’s mind, such a show should focus not on folk dances but on what his fellow Vietnamese truly excel at, such as gambling, smoking, drinking coffee in cafés, and “gossiping about our friends and relatives, whom we loved to backstab even more than stabbing our enemies, whose backs were harder to reach.” He observes that the French love American jazz “partially because every sweet note reminded them of American racism, which conveniently let them forget their own racism.”

“Ah, contradiction! The perpetual body odor of humanity!” the Captain proclaims. “No matter our nationality, we all got used to the aroma of our own contradictions.” This is a less exalted notion of humanity than the ideologies he has dabbled in, but a more truthful one. It’s a view ill-suited to either a revolutionary or a gangster, but it is exactly what’s called for in a writer.