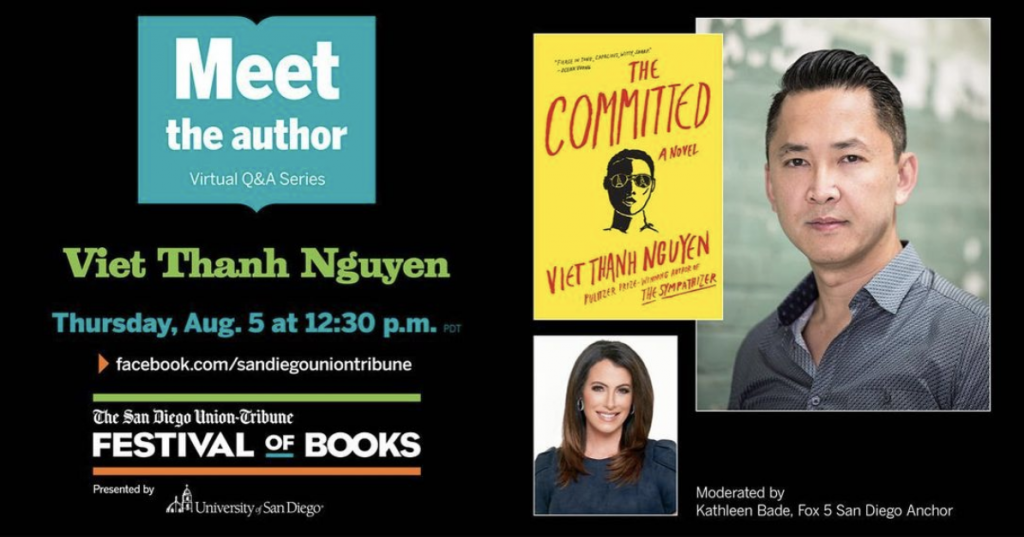

Viet Thanh Nguyen is interviewed by Kathleen Bade for The San Diego Union Tribune Festival of Books.

Watch the interview on Facebook or read the full transcript below.

Kathleen Bade: Well, welcome everyone. I am so excited for you to be here. I’ve been chatting with this wonderful man right here you see on your screen. But first, I want to welcome you to the San Diego Festival of Books Meet the Author Q&A Series. My name is Kathleen Bade. I’m the primetime anchor for Fox 5 San Diego. I’m just so thrilled to be here. I finished this fantastic book this morning. My mind is still swirling from how beautifully it’s written and just the story itself.

Kathleen Bade: Let me introduce the author behind this magnificent piece of work. It’s a much anticipated follow-up. This is Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Viet Thanh Nguyen. This is his new book The Committed. People have been waiting for this puppy, because the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Sympathizer, is the book that preceded it and really just was so widely praised by critics and received so well.

Kathleen Bade: The Committed is actually, as I mentioned, a follow-up and it picks up in Paris in the 1980s where this conflicted double agent, this man of two faces and two minds seeks refuge in Paris and tries to build a new life. Viet, enough of my talking, I know everyone wants to hear from you. First of all, so nice to meet you. Congratulations on your follow-up book here.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Kathleen, it’s such a pleasure to talk to you today. Thanks for having me.

Kathleen Bade: Well, the question I want to start with, two of them actually, is what I have been asked every moment that I’ve posted that I’m going to be talking to you. First and foremost, do you have to have read The Sympathizer in order to understand and enjoy and get The Committed?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Absolutely not. Although why people have not read The Sympathizer? I don’t know. I think it’s pretty good. But I wrote The Committed very deliberately to be a standalone novel. You just jump right in. There’s enough clues and backstory to get orient the reader right away. I’m a fan of genre fiction like detective and spy stories. If you read these kinds of things, you know that they go on for series. They go on for dozens of volumes sometimes.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: You can just jump right in and immediately read a book without having to read from the first to the end. As part of the ambition is to do that. Now that being said, if you’ve read The Sympathizer, there’s a lot of continuity. These two books are part of a larger project. Supposed to be a trilogy. If you have the luxury of the time to sit there and read them both back-to-back, that’d be great, too.

Kathleen Bade: Well, let me ask you then about the pressure. When you have a book that is so well received, like the Committed, I mean … or excuse me, like The Sympathizer and now The Committed has had wonderful critical reviews as well. What kind of pressure did that put on you for this second effort that this book rise to the occasion of The Sympathizer?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, the real pressure that I had was trying to be a writer. I had all these fantasies of becoming a writer when I was a kid. Then I started writing in my teens and 20s. I thought, “Oh, I’m going to write for a few years. I’m going to publish a book. I’ll be famous.” Of course, I wasn’t that talented. Didn’t work out that way. It took me about 20 years of practicing and trying to write before I really felt confident enough to call myself a writer.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Now during that time, I felt a lot of pressure. Would anybody read my stories? Would anybody buy my book? What would the editors, an agency, what I’ve been prices and all that. During the 20 years of struggle, all that pressure was eventually something I learned how to deal with and stop caring about. When I wrote The Sympathizer, actually, what I did was say to myself, “This book is for me. It’s not for anybody else. I’m going to write it exactly the way I want to. I don’t care whether anyone ever buys it or reads it or whatever.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: That was enormously liberating. I had no pressure, almost no pressure writing The Sympathizer. Then I was very lucky and won the Pulitzer Prize. I think if I had thought about it in a certain way, it could have been a lot of pressure. I have to equal The Sympathizer and so on, winning the Pulitzer Prize and so on. But really my mindset was “it’s liberating,” because I don’t have to prove anything anymore. I don’t have to win anything anymore. I can still write The Committed just for me, and hope that other readers come along.

Kathleen Bade: You’ll have that Pulitzer Prize-winning author next to the name for the rest of your life. Have you been wrapped your brain around that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I have it tattooed on my body somewhere, but you don’t know where. Just kidding.

Kathleen Bade: There’s that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. I think that there is that. I mean, where I’m introduced, people make sure to say it. Even when I give people bios, I say … I don’t include it. People’s like, “Don’t you want to mention it in your bio?” I think that people do take a lot of recognition from the prize and what it means and doesn’t … the symbolism of it. I respect that. For example, when The Sympathizer came out, a lot of Vietnamese people didn’t want to read that novel because it’s written from the perspective of a communist spy.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: A lot of Vietnamese Americans are anti-communist for obvious historical reasons. But The Sympathizer won the Pulitzer Prize. Then all of a sudden Vietnamese people were proud of me. Like, “Yes, we claimed you back for the Vietnamese people.” I think of people are so proud of that, for all the obvious reasons that I’m happy for them, and I’m happy to be that representative.

Kathleen Bade: Well, that kind of brings me to a question I was going to ask later. But I’ll ask it now, because you brought that up, the Vietnamese culture. Because what I found so interesting, as somebody who hasn’t had my feet wet in that genre at all is the collision of these two cultures that you put together in this book, the Vietnamese culture and your lead character whose father is French.

Kathleen Bade: He goes to France. Can you talk about the intersection of those two cultures, because they are two that I would just never put together?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. Well, the French colonized Vietnam for well over 100 years. Then the United States came in 1954 to take over the French colonial project. It’s really impossible to talk about what happened in Vietnam during the American period, what the Americans call the Vietnam War from what happened before with the French. That’s something that Americans tend to forget.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: In The Sympathizer, what I set out to do was talk about the American phase of Vietnamese history and the impact on the Vietnamese through that war, and then what happened to the Vietnamese when they came over. What I tried to do in The Sympathizer was honestly offend everybody. I think I succeeded judging from the hate mail. But I really felt that The Sympathizer, the French gone off pretty easy.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I deliberately made my protagonist part French, part Vietnamese, bring in French colonial history. But it really took The Committed to be a book where I could finally try to hold the French to account for all the terrible things and some of the good things they did through colonization.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: One of the things that happened was the French and the Americans produced this hybridized culture of westernized Vietnamese people in Vietnam, who then also migrated out as refugees or immigrants to France and the United States, and did wonderful things like invent the banh mi, which is a Vietnamese sandwich, that’s a creation from the French baguette.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Honestly, the Viennese banh mi is better than any French sandwich that you will ever taste in France. That’s just one example of the ways that Vietnamese people have used their colonial history to create a new culture. Here in the United States, of course, in San Diego, Orange County, San Jose where I grew up, and many other cities throughout the United States like Houston, and Arlington, Virginia, there are major Vietnamese-American communities that have existed by now for, I think, 45 years, firmly entrenched as Americans.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: But also very conscious of themselves as Vietnamese people with Vietnamese language, Vietnamese food, Vietnamese politics, it’s a very complicated and wonderful place, and set of communities to live in, and also be potentially dangerous and conflicted as well, just some of the things that got brought up in these two books.

Kathleen Bade: Oh, my goodness. There’s so many dualities and conflicts and conflicting ideas in this book, and you raise so many questions, whether it’s capitalism versus communism, or even nothingness versus doing something. There’s so many questions that you let swirl around in the reader’s head. But you don’t provide a lot of answers. That was your intent, was it not, to get your readers just thinking about flipping things on their side and looking at them differently?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: There’s a couple ways of approaching that question. I think F. Scott Fitzgerald, for example, said that the sign of a … trouble quoting people, the sign of incredible mind or good mind is being able to hold two opposite things in balance at the same time. That’s one thing that these two novels tried to do. Because I think there are a lot of people, whether they’re Americans, or Vietnamese, or French, who are not very good at keeping two opposing things in mind at the same time. They just want one thing.

Kathleen Bade: Especially these days. Especially these days.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Especially these days. Right. In complex situations, there are some people who want a simple answer, one answer, no ambiguities, no dualities, nothing like that. Unfortunately, I think … or fortunately, if you are a refugee, or an immigrant or so-called minority of whatever kind in the United States or elsewhere, it’s really hard, I think, to live with only one answer to a problem, because you’re always feeling these tensions of conflict.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Am I Vietnamese, am I American, and so on and so forth. I grew up that way, feeling that way. I took that feeling, and I amplified it, because my life is not very interesting. Amplified it in these dramatic stories of The Sympathizer and the spy messes that he finds himself engaged in. In truth, he’s searching for an answer, as I think many of us are. But it would seem false, I think, if I gave a concrete answer to all the various questions that he raises.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Partly that’s because as times change, answers that might be sufficient at one time, may not be sufficient at another. For example, talking about the war in Vietnam, I think at one time, it was probably the right answer to revolt against the French and revolt against the Americans. Yet now, if we look at Vietnam, the successful communist revolution has also become a successful state that oftentimes represses its own people.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: That’s part of the ambiguity that these two books raise. I think the only thing that The Sympathizer itself really stands for is a constant interrogation of injustice. What happens when the powerful abuse power?

Kathleen Bade: For a land of refugees, it’s certainly every one of the people who are here in America at one point came from a band of refugees, frankly. It’s, I think, so insightful to look at it through a different lens. I pointed this out on page 35. Which before I read it off, I want to remind everyone that you can, I didn’t mention it earlier, submit questions through Facebook on the chat. I hope you do so. You can ask Viet what you want to know about these books.

Kathleen Bade: But on page 35, I wrote this down because I thought it was … I think it illustrates how you write and how you think, and how you frame things looking through something as simple as being a refugee and coming to this country seeing it through a different lens. You wrote in here with your lead character, and I hope I say his name right, because he’s usually nameless, and I’m not sure I’m supposed to call him Crazy Bastard on here.

Kathleen Bade: I just did. There you go. But Vo Danh is that how you say his name?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. Crazy Bastard is the nickname that’s given to him. But he also has a passport with a name on it called Vo Danh, which in Vietnamese means anonymous. It’s his joke on the French bureaucracy.

Kathleen Bade: All right. I’m glad I got that pronunciation. But he writes, or you write in his voice, “I was not a boat person unless the English pilgrims who fled religious persecution to come to America on the Mayflower were also boat people. Those refugees just happened to be fortunate that the soon to be hapless natives did not have a camera to record them as foul smelling, half-starved, unshaven, and lice-ridden lot that they were.”

Kathleen Bade: In contrast that you talk about that the boat people were not human, and they didn’t have the benefit of some romantic painter, casting them in oils. I was fascinated by that. I wanted to point it out to people who are watching because it’s how you reframe some of these things that I think is so mind-blowing. Can you speak to that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, I think that every people, every culture, every nation wants to glorify itself. It’s not just Americans or Europeans or the English who do it. The Vietnamese do it, too. Like I said, for the sympathizer, his project is not only about asserting what it means to be Vietnamese, or mixed race Vietnamese. His project is also always constantly interrogating power and mythologies and things like that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: He really does it for every group. But in this particular passage, he points out that the American mythology of the founding of this country and so on is obviously enormously meaningful for Americans. We’ve all absorbed. I grew up here. We have all absorbed these ideas of the pilgrims and the Mayflower and all of that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: But common sense tells you that if you spent months crossing an ocean in the 17th century on a little tiny boat without showers and toilets, and all that, and shaving cream, you’re going to look pretty nasty and smell pretty nasty by the time you get to shore. But of course, we don’t think about that, because we’ve mythologized our own origins. Again, everybody does that. The Vietnamese do it, too.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: If anybody out there is worried, trust me, I hold the Vietnamese to account for many terrible things that they have done, too. I think it’s really crucial for The Sympathizer and for myself in these novels to criticize, but also to have fun, making fun of these kinds of mythologies.

Kathleen Bade: Well, let’s get to the crux of the story so that people can dissect what you’ve written and interpret it. Can you bridge us from what happened with your lead character, the double agent, the spy, this man that you call … Is it two minds and two faces?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: A spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces and two minds, right. Yeah.

Kathleen Bade: With the faulty screw that’s holding them together, which I think we all are just one faulty screw away of falling apart. But can you bridge us from The Sympathizer? What happened there and where The Committed takes us?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Sure. In The Sympathizer, it starts in April 1975, which is the month when Saigon falls or is about to be liberated depending on your point of view. Our man of two faces and two minds, obviously, it can see things from both sides. He’s a communist spy in the South Vietnamese Army. When the city falls, his mission is to fleet with the remnants of that army to the United States and spy on their efforts to take their country back.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Let me just say, all of this is based on things that really did happen. Long story short, he does make it back to Vietnam. Things turn out badly. He ends up in a reeducation camp as a prisoner of the communists, who were once his allies. The end of The Sympathizer is when he escapes from Vietnam to become one of these so-called boat people.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The Committed picks up exactly where The Sympathizer leaves off in the early 1980s. Except that now he’s made his way to Paris to confront his French heritage, because his father is a French priest. In The Committed, because he’s been deeply traumatized by the events of The Sympathizer, he makes some very bad choices. He becomes a drug dealer, or in other words, a capitalist.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: He works for this ethnic Chinese-Vietnamese crime boss in Paris. He also hangs out because of his aunt who is living with the French intelligentsia, the left wing, the elites, and all that, all those kinds of things. On one hand, this crime thriller; and another hand, a satire of these French pretensions in the French left. That’s what the novel is. Hopefully, it’s a lot of fun, even as there is a lot of sex and violence and drugs and a lot of discussion about ideas around politics and liberation.

Kathleen Bade: Yeah. You have this constant inner dialogue where it’s almost he’s trying to find himself. He’s this strange character of someone who … Having endured the reeducation camp and torture, and even in The Committed, as well as The Sympathizer, being tortured and living this gangster lifestyle. He’s so resilient and strong in one aspect, but then he cries at the drop of a hat all the time.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Let me just say one other thing. I think the novels are funny, in addition to all the violence and the torture, and all that other stuff as well. I mean, I was inspired by books like Catch 22, for example, in which you get the mix of both tragedy and comedy. The Sympathizer, I think, is, in my mind, someone who is potentially in every man except taken to an extreme, because I think inside many of us there lurks this sense that we are not what we seem to be.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: When we present ourselves to other people, we’re putting on a face or a mask of some kind. Yet, there’s something else behind it. Now, he takes that to a much greater extreme, because of the conditions that he’s living in. You mentioned, the idea of there being a screw loose, which is something I mentioned in The Committed. Again, he has two minds that are being held together by this screw.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: That screw has been greatly undone by all the trauma that he’s gone through. But I think that many of us at certain moments in our lives have felt the screw coming loose under certain kinds of duress. Getting tethered to the truth.

Kathleen Bade: This last year alone, right?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yes, yes, exactly. I’m going to write a story about how in the fall of 2020, during the presidential election, I went a bit crazy. Okay. I said things. I did things. That I regret now under the pressures of those times. He’s under even much greater duress. Novel is told, The Committed, only from his point of view.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: He is not in the position to say, “Hey, I have post traumatic stress disorder.” Instead, we have to feel through what he’s saying, what he’s thinking, what he’s experiencing the effects of trauma. That’s manifested in the way that the story is told.

Kathleen Bade: His relationships are interesting, too, because love is a central theme, too, as much as there is humor and some sarcasm and how he assesses different rooms he enters and how he reads people. I think is where a lot of the humor lies. But he also is the son of a father, who was a French priest who never basically disavowed him and was never a father to him. Then has a mother that he constantly reveres and worries about even though she’s passed on what she’s seeing him do in this life and the choices that he’s making.

Kathleen Bade: Then he has this love of his deep friendship, his blood brother of Bon. Can you talk about just really for a man who isn’t experiencing much love in his life, that there is a lot of love central to his … and the thin line between love and hate when it comes to his father, but it is a central theme.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Sure. Well, our sympathizer across these two books is a liar, an alcoholic, a womanizer, a spy, a trader, a murderer. You can see it’s completely autobiographical. I do [crosstalk 00:19:13] life experiences. Yeah. The challenge there is how to make somebody like that lovable or at least interesting or at least identifiable in some way. Partly, I think it’s through the … That’s his humor, his ability to criticize and satirize, but also his self-critique.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: He’s quite aware of all the terrible things that he is. Then finally, like you said, his capacity for love and loyalty. I think that his relationship with his mother, who was molested by this French priest, as a young girl, the pederastic relationship produces him is an allegory for colonization in general. But out of that, he is this Crazy Bastard, but he loves his mother or her memory really, really deeply. He loves, like you said, his friends.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think that is something that readers can connect to that it’s perfectly possible to be this really complicated person who does some things that we might object to as human beings. Yet at the same time also does things that we understand as very human things in terms of love and compassion, and loyalty as well. To me, that’s one of the central points of these novels. It’s that humanity can’t really be reduced to simplistic things.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I don’t think most of us are just all good people all the time. Likewise, people who do terrible things are usually not terrible people all the time. Most of us are mixed. That’s part of the complexity that I think literature and art is supposed to get at.

Kathleen Bade: Well, it is fascinating. I’m a big believer in taking the totality of a person. I found that so fascinating, because none of … I mean, we’re all nuanced in so many different ways and so flawed. You also bring up in the book, I mean, it’s the title of the book, The Committed. But you also once again, put it whether it’s committing suicide, whether it’s committed to the cause, whether it’s committed to an insane asylum.

Kathleen Bade: You use it in multiple ways. Explain what you mean by The Committed when you use then as the title of the book, what that encapsulates for you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: There’s a lot of wordplay in both of these books. That was fun for me to do as a writer. It speaks to the fact that our sympathizer is someone who grows up in Vietnam, speaks Vietnamese, but is also trained in French at an early age, and then become fluent in English, because he goes to the United States to study. This is all based, by the way, on the life of a real Vietnamese communist spy who came to Orange County to study in the 1950s, and then became perhaps the most important spy for the communist side.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I took those kinds of ideas. I thought, someone who’s like that is able to see not just any issue for both sides, but is able to see languages from both sides or from the outside as well. That’s one of the reasons why there’s such intense focus on wordplay in these books. For The Committed, that term itself, I was thinking of how when we look at the history of revolutions, people who are revolutionaries are very committed. They’re totally committed to their cause.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: They do these things. They do these revolutions in the name of the greater people. They’re doing these things out of love, and out of a desire for justice, all these good noble causes. Yet, when you look at the outcomes of certain revolutions, you can see sometimes that they have gone too far. At what point does commitment go from a commitment to love and justice and liberation to being committed in the sense of being insane?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The novel invokes various times when that happens. But most obviously, through one of the subplots, it talks about what happened in Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge rule and the genocide. The reason why that’s important is because what happened in Cambodia was an outcome of both French colonization and what the United States did in carpet bombing Cambodia and helping to bring the war there to Cambodia and the North Vietnamese participated in that as well.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The Khmer Rouge cadres, they were all the upper cadres French students. They all went to Paris. They studied the City of Light. They absorbed all these French and Latin theories. Then they came back and they applied them and this applied them to the extreme in Cambodia. That’s just one example of the way by which commitment can go too far.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Our sympathizer he’s caught in the middle of that. He feels that in his own way that maybe he’s done the same thing, that his commitment to a revolution has sometimes taken him too far.

Kathleen Bade: Yeah. You certainly hand out the culpability. It’s spread out and makes you think about all sides of … We like to think about wars or conflicts of just one or two. But there’s usually so many hands in the pot. I think you write that so well. You also talk about, which I found really fascinating, the concept of nothing being something. Explain what that notion means to you in the book.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: In the early 2000s when I was studying Vietnamese in Vietnam, there was a joke that was going around. It was based on the fact that the most famous political slogan in Vietnam then and now was from Ho Chi Minh, who said, “Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom.” This is something that every Vietnamese person knows and it’s part of Ho Chi Minh’s legend.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, the joke at the time, because Vietnam was going through all this economic growth and this political transformation, it was a communist country that was actually a capitalist country. You had a communist party in charge of a capitalist economy. It was strange. That’s still the case. The joke was that nothing is more important … Nothing itself is more precious than independence and freedom. Reversing the meaning of what Ho Chi Minh was talking about.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I thought that stuck with me. Appropriate time in The Sympathizer, I brought that as a joke near the end of the book. It resonates with the fact that in The Sympathizer, there’s a moment in The Sympathizer towards the end, when The Sympathizer acknowledges that he should have done something, but instead he did nothing. In The Committed, I wanted to continue this investigation of nothing because some readers reached the end of The Sympathizer, they said, “You’re a needless. You believe it nothing.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, that’s not what I’m arguing. I’m arguing that in nothing, there is something. Again, going back to this idea of duality and wordplay, we can’t reduce things to a singular meaning. Sometimes, as we see in The Committed as they continue this investigation of nothing, we should do nothing, instead of something. I can’t tell you what it is, because that’ll give away a key part of the plot.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: But again, nothing and something are constantly in relationship to each other. It’s not that one is better than the other. I think we live in a culture that says something has to be better than nothing. I think in reality, if we turned to other kinds of philosophical systems, or religious systems, sometimes nothing actually has great meaning. Absence has meaning. The void has meaning in religions like Buddhism, for example. All of that is filtering around this plot, in this action, in this meditation on nothing in these two books.

Kathleen Bade: You mentioned this being a trilogy, that’s what you were setting out to do. You’ve written the Pulitzer Prize-winning, The Sympathizer. Now you have The Committed on your bookshelf. Do you have a title for the next one?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, I have one, but my wife just told me she didn’t like it. I’m just going to survive. Yeah. But I’ve been saying it’s called The Unfinished, because I think we were talking about this earlier, before we got on camera. When you’re asking about answers, and I was saying “That sometimes, the answers are not enough, because situations change.” I think the third novel would definitely be the last novel of the trilogy.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Having watched a lot of serial TV, I’ve realized there’s a good time to end a series and a bad time to end the series. It’s something a good time to end it. But even though it’s going to end, it’s going to be unfinished. I mean, it’s going to leave questions unanswered, as I think always is the case in our life, but also in history and in this political situations and the personal situations that The Sympathizer confronts.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The Unfinished what will happen is he does make it back to the United States through a very circuitous route into the latter half of the 1980s. I’m not sure what your decade is Kathy, but the 1980s is my decade. It formed me. It shaped me. This is my opportunity.

Kathleen Bade: Unfortunately, I’m right there with you, with the parachute pants and …

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Parachute pants, big hair, Ronald Reagan, Star Wars, crack, all this stuff is going to take place in LA in the 1980s. Again, lots of sex, drugs, violence, and crime, along with all these meditations about …

Kathleen Bade: You’re right there in the thick of it as a writer in LA. Tell me, we’re almost at the end here. But what is your process like? Because being a writer and an author sounds so exciting. But before we were on camera you were talking about it really is a life of torture?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. I say this. Some people say, “Don’t say that. Say that’s it, that writing is fun and it’s enjoyable.” There is a dimension of it in which it is fun and enjoyable. Not as with this notion of duality, it can’t only be that. It’s also about struggle, and persistence, and discipline. I was telling you beforehand that I spent 20 years working on a short story collection called The Refugees.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Let me just say this. In California, in other words, I spent about 10,000 hours struggling to become a writer. Now, if that was in Vermont during the winter, that’s fine. But 10,000 hours in California, most people I knew were hiking or swimming or snowboarding or whatever. I was in my room.

Kathleen Bade: You’re a shut-in.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: It was not this nice room that you see. I was writing looking at a blank wall. Okay. That’s part of what it means to be right at the process is putting your butt in chair and writing. I like to say, “You don’t have to write every day. But you do have to write a certain amount over a certain amount of time.” You can do 10,000 hours in 10 years, 20 years, 40 years, it doesn’t matter. But you have to do something like that in order to become a writer.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Now the other part of my process that I’ll mention is I drink a lot that really helps at the end of the day. After I really … I’m really exhausted mentally from all this concentration. I do like to have three or four fingers of Scotch.

Kathleen Bade: Well, his drink was I believe it was whiskey that he liked in the book. We are drawing some parallels. I sadly really related to the just being held together by the faulty screw. I thought, “Boy, a lot of us … we’re just one screw away from everything is falling apart.” You also said that you had dreams of becoming a writer as early as third grade. What was the very first thing that you wrote?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: In the third grade, I wrote and drew a book called Lester the Cat for school. It won a prize from the public library, which was great at the time. I thought, “Oh, I’m a writer.” Then that prize set me on the road to 40 years of misery trying to become a writer. Thank you San Jose Public Library.

Kathleen Bade: Well, tell me is any chance that Lester could become a children’s book?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. It’s possible. But I gave it to my girlfriend at the time. When she broke up with me that is dumped my sorry ass, she also took the book. I haven’t seen it. I don’t know where it is. But maybe I can recreate it with my son. My son and I, he’s eight years old, we did a book together called Chicken of the Sea, which is actually all his idea, came up with it when he was four years old.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: We turned it into a children’s book. Now, I have this other career. I’m doing another children’s book right now as well. It’s really one of the benefits, I think, of having kids, which I never anticipated.

Kathleen Bade: Well, what a strange juxtaposition having read your book. It’s a spy novel. They become gangsters and drug dealers, and all of that. Then you’re also on children’s bookshelves. That’s quite a downshift, isn’t it?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. I would like to say that Chicken of the Sea, this children’s book has no redeeming moral value at all. I mean, I think it’s great when children’s books have redeeming moral values. This doesn’t. Okay. It’s about four chickens on a farm who are so bored that they run off to become pirates. I’m not sure what lessons you can draw from that, parents, but besides the fact that the book is a lot of fun. That’s all the book has to say.

Kathleen Bade: Oh, that’s fantastic. Well, we’re getting a lot of comments here from people who want to talk to you. I’m going to read some of these questions and find out. We’ve got Christine here. Just because I’m a fiend when it comes to privacy, I won’t do last names. I always worry about people. But she says, “Hi, Viet. What was the most challenging thing about writing The Sympathizer and The Committed?”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Thank you, Christine. Writing The Sympathizer, the hardest thing, actually, I had two years to write The Sympathizer. I was very lucky because I’m a professor. But I had two years off from teaching due to fellowships and sabbatical. I was devoting my entire life to writing The Sympathizer for two years. It was a blast. I had so much fun.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The only bad times were when I talked to my agent, because as I said, I was writing this book for myself. But when I talked to my agent, my agent was like, “Where are you? Are you done? When would I get to sell this book?” I was like, “Oh, no. I have to think about selling the book.” That just stressed me out. With The Committed the hardest thing was, I wrote the first 50 pages. As I did in the same spirit of The Sympathizer a lot of fun.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Then I was lucky enough to win the Pulitzer Prize. My life turned upside down. Whereas The Sympathizer took two years, The Committed took four years, because my life was so interrupted by various kinds of obligations, and so on. I have a hard time saying “no.” It was just not as fun writing The Committed as it was writing The Sympathizer.

Kathleen Bade: Did you ever fear that you didn’t still have it in you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Oh, yeah. I was like … Because with writing The Sympathizer, it felt like a dream. It was a very continuous experience. That’s the way the book is meant to be experienced as well. With The Committed, it was an interrupted dream. If you can imagine having this wonderful dream, you have to wake up every five minutes. That was what it was like and it takes a while to sync back into the dream.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I thought, if I’m not having the dream myself, will the book have that same flow that The Sympathizer did. I was like, “I have no idea. I will just have to put it out. Let readers figure it out.”

Kathleen Bade: Well, as you’ve been talking, I think you’re the perfect person to answer this next question, because we have a young, inspiring writer here named Mason. He said, “For someone in their 20s who’s interested in becoming a writer with a nonexclusive focus in poetry do you think it’s helpful or essential to attend an MFA grad program in creative writing? Writing seems like most industries and that it’s about who you know. Does that notion make grad school more relevant to aspiring writers?”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: That’s a very good question, kind of complicated. I took a few writing workshops as an undergraduate and graduate student, but I never did an MFA. Mostly because I knew I sucked as a writer when I was 20 years old. I was never going to get into an MFA program. What basically happened is I taught myself how to write. Again, I think the basic truths of writing are simply this. You write a lot, and you read a lot, widely and deeply.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

If you can do those two things, you can become a writer, and you don’t need an MFA program. Now, the MFA program can shorten the time of learning how to write because you get to hang out with students and master writers or better writers than your professors who can tell you things, teach you things and all of that. The drawbacks to that would be, number one, I would strongly encourage people not to go to writing programs where they have to take on debt.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: We know we’re living in a period where college debt is really a heavy burden on people. You have to think about whether it’s worth it to spend two or three years learning how to write if you’re going to come out with $100,000 in debt. If you can get a fellowship, I would say go and do it, because that’s just free time for you to write.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Mason brought up the fact that there are connections to be made, and I think that is true. I mean, you are going to meet writers there, including your professors who can open certain doors for you, connect you to agents and editors and so on. That might be very worthwhile to do. That did not happen to me. The way I got published was I just kept sending out short stories, kept getting rejected, some of them got published.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Then my agent read one of my short stories. That’s how I broke through without any kinds of introductions. But those introductions, those networks can be something of a shortcut. But again, I would just say, you would have to ask yourself, “How much is it really worth to you financially? That’s the only decision you can make.”

Kathleen Bade: Here’s another question. Dorsey asks, “As a writer myself, your writing is very fluid and well-paced, sometimes fast, yet other times I felt I had to take my time to read. Can you share your writing style from the reader’s perspective?”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Great question. I mentioned, I like to read detective stories and these thrillers and all that. When you read those types of things, one of the things that are very obvious is that the language is not meant to get in the way. You’re supposed to read these books very, very quickly, get to the end, and all that. I love that reading experience.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The problem is sometimes I read series of detective stories, whatever. I cannot remember when I tried to come back and pick the series up, where I left off. I can’t remember if I read this book or that book, and so on so forth. It’s something that’s one of the drawbacks of a very transparent writing style in the genre, well, genre fiction. With The Sympathizer, I wanted to both capture the some of the thrill of reading so-called genre fiction, as you said.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: But I also wanted to, as you said, slow things down and make readers read twice. This is why. Because I also enjoy reading literature that makes me look at the language again, and again, and again. That’s not true for everybody. It is true for me. I don’t have a problem, for example, reading Moby Dick, or reading William Faulkner, reading writers whose prose is so dense that sometimes I can only read a couple pages at a time as if they were poetry.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: That’s what The Sympathizer and The Committed tries to do is to bridge these two different kinds of writing between so-called genre writing, and so-called literary writing. I believe there are readers out there who have similar tastes as mine, but also crossed that bridge.

Kathleen Bade: Pamela asks if you have any upcoming projects in the works. You already mentioned the third book, The Unfinished, so far. But I think you also need to bring up how your life is intersecting with Iron Man. I think that’s critical.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, I mean, I will talk about that just a moment. But the project I’m working right now is a nonfiction book that is partly memoir, partly a cultural critique. I’m in the middle of it. Here’s a little clue to the writing process. I finished the first draft at 68,000 words, I’m looking at it right here. 68,000 words and I’m revising it. I’ve already cut out 8,000 words, and I’m not even halfway through the book yet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Part of the writing process is revising is cutting. It actually feels pretty good. One of the hardest parts about writing is just to get that first draft down even if it looks terrible. This first draft has not looked so good. But I wrote 69,000 words now. I can cut stuff out. Then the other thing I’m working on right now is, as Kathleen said, the TV adaptation of The Sympathizer. This means that there are some of you who won’t have to read the book at all.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: If you don’t want to, you can just go see the TV series, hopefully done in a couple of years. But what happened was that we did sell this TV series to HBO and it had to be a TV series, not a movie. Because when I was writing The Sympathizer, I was watching a lot of TV. I hadn’t watched TV for a decade before The Sympathizer and then walked right into Synthesizer with all my free time. I watched The Wire, Madman, Breaking Bad, The Sopranos, and I was very influenced by that serial TV structure.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: You can totally see it in the fact that The Sympathizer is 26 chapters all the same length. We’re going to do this TV adaptation. Iron Man comes in because Robert Downey Jr. is going to be playing, not The Sympathizer as some people freaked out like, “Robert Downey Jr. is going to play The Sympathizer. He’s not Asian.” Robert Downey Jr. is going to play all the white guys in the book, which I think is a stroke of genius on the part of the director, Park Chan-wook.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Evidently, Robert Downey Jr. thought so, too, for him to sign on. Now I am officially cool in the eyes of my nephews, my nieces, and my eight-year-old son who understands who Iron Man is.

Kathleen Bade: You finally got some street cred. I mean, put the pillow to the side. You might meet Robert Downey Jr. I’m going to probably butcher this name. Please correct me. Christie writes, “I see a Thi Bui book.” Is that how you say it?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Thi Bui.

Kathleen Bade: Oh, I’m sorry.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Thi Bui.

Kathleen Bade: Thi Bui?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. Yeah.

Kathleen Bade: Thi Bui book that actually sounds so much better.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Right.

Kathleen Bade: Book on your shelf. Are there any Vietnamese or Vietnamese-American authors or creators you would recommend?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Sure. Here’s Thi Bui’s book. It’s the best we could do for those of you haven’t heard about it. It’s a terrific comic book memoir about the refugee experience and life in Vietnam. It’s deeply moving book. Because it’s a comic book, you can read it pretty quickly. There’s so many, so many good Vietnamese-American writers out there right now. Let me just think off the top of my head.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Nguyen Phan Que Mai who you might have a hard time writing her name. But her novels called The Mountain Sing. I blurbed it as being Arc Ribs of Wrath for Vietnamese people. It’s a really epic and moving story about Vietnamese life from the 1940s through the war. Eric Nguyen, same as my last name has a new book out, Things We Lost to the Water, which is about the refugee experience as it intersects with New Orleans, Louisiana, and Hurricane Katrina.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Ly Tran has a new book out called House of Sticks, it’s her memoir of coming to the United States and being inserted into New York City where her family has to start a nail salon. This is one of the universal experiences. Most people have been to a Vietnamese nail salon or have one in their neighborhood. House of Sticks shows you what it’s like from the other side, from the people who have to work there.

Kathleen Bade: It’s really interesting. These different perspectives and how important those voices are for us to hear. You write in the book, “Power indeed comes from the barrel of a pen.” I think you’ve certainly proved that with your books so far. Viet Thanh Nguyen, we thank you so much for your time. This has been a wonderful conversation.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Kathy, it was so great talking to you. To the people in the audience, thank you for your questions. Thanks for showing up.

Kathleen Bade: It was really an honor just to meet you. I, too, fall right into that category. I see Pulitzer Prize-winning author, and I think, “Wow, what an accomplishment.” Congratulations on that. For those of you who enjoyed this conversation as much as I did, I hope you did. Viet returns to San Diego Union-Tribune Festival of Books on August 21st. That’s right around the corner.

Kathleen Bade: You can order his books through the Festival bookstore. The link is noted at the bottom of the screen. By purchasing his book through the Festival bookstore, you also support festivals, indie bookseller partners who are invaluable to the community. The author conversations continue, like I said, August 21st, and mark your calendar down. San Diego Union-Tribune Festival of Books with Spanish language panels, which will be wonderful, presented by the San Diego Union-Tribune en Espanol.

Kathleen Bade: Watch an incredible lineup of award-winning poets and storytellers. This year Grammy Award-winning singer and songwriter, Kenny Loggins, this sounds so fun. He’ll be joining for a special appearance featuring his children’s book, Footloose. Viet has some children’s books and so does Kenny Loggins. Hashtag, grab a book and join us. You can visit the festivalofbooks.com to see the complete list of authors and events.

Kathleen Bade: We thank you all so much for tuning in for this and especially to Viet Thanh Nguyen. Congratulations. The confidence that you didn’t have along the way, I hope you’re blanketed in it now because you are a beautiful writer. I really enjoyed The Committed. I thank you for making me think about things differently and from a different perspective. I really appreciate that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Thanks again Kathleen. Bye everybody.

Kathleen Bade: All right. Take care.