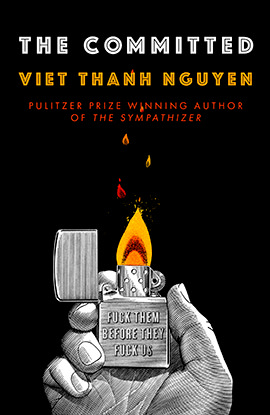

Randy Boyagoda writes a review about The Committed for Financial Times.

With the release of his brainy, brawny second novel, The Committed, Viet Thanh

Nguyen surpasses his most prominent American literary influence: Ralph Ellison

never published a successor to his 1952 novel Invisible Man.

Ellison’s only major work was everywhere present in Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize-winning

2015 debut, The Sympathizer, which established its author as a major voice in

contemporary American letters, a position only strengthened by Nguyen’s other

writings about geopolitical migrant life since. The Sympathizer concerned an

unnamed young man figuring out his place in the world while negotiating between his

Vietnamese past and American present, and between the formative traumas of

refugee, exile and immigrant experience in the aftermath of the Vietnam war.

This novel could have been little more than an especially political variation of an

American newcomer tale but for the Ellisonian boldness of its narrative voice —

playfully caustic about self, other and America — and its taut premise. The

Sympathizer is a spy for Communist superiors in Vietnam, both reporting on and

seeking to disrupt the work of anti-communist dissidents in Los Angeles, including

one of his very closest friends.

With The Committed, Nguyen transports him from Vietnamese enclaves of late 1970s

California into a dark new world: the demimonde of early 1980s Paris, where drugdealing gangs, entrepreneurial immigrants and leftist intellectuals mix to decadent

and dire excess.

This change of setting and demographics reframes the here-and-there, past-and-present dynamisms of The Sympathizer away from their predominantly US-Vietnamese contexts. In The Committed, Nguyen details the corrosive after-effects of

French imperialism — in relation both to Vietnam and to the Middle East and north

Africa — on a cast of swaggering and unapologetically seedy Parisians.

On his arrival in Paris, in his late 30s, and continuing his involvement with “blood

brothers” Bon and Man, whose mutual animosities only he fully knows and is

implicated by, the Sympathizer begins to establish himself in seamy city life. He works

as both a bottom-rung restaurant worker and an exotic drug dealer to the cerebral

social circle of his cynically cosmopolitan “Aunt”, a Franco-Vietnamese intellectual.

She helps him and his friends find their way in their new city and expects loyalty and

kickbacks for her efforts.

The Sympathizer is game, adept and very quickly becomes addicted to drugs himself.

The effect, combined with his already-divided sense of familial, cultural, religious and

political affiliations, produces vertiginously split first-person storytelling. This further

complicates his accounts of becoming caught up in brutal conflicts involving members

of the Vietnamese-Parisian crime scene and also with a rival French Arab gang whose

members go by sobriquets such as Sleepy, Mona Lisa and Rolling Stones.

The plot is shaggier than high-pile carpeting, and features many unsettling sequences, particularly at a nightclub called Heaven, and also in its scenes of kidnapping and violent interrogation. Telling the story occasions a great deal of polemical wordplay on the part of the narrator about what it means to be a knowing arriviste in the imperial metropole: “WE pointed at a thick oval of rustic bread that WE had never ordered before but about which WE had been curious ever since learning its name, which WE now pronounced in the most perfect French by saying, I’d like a bastard if you please.” (The emphasis is Nguyen’s own).

Less incisively clever and far more self-righteous are his endless monologues, thought

and spoken, about identity, ethics and action, as when the Sympathizer explores his

“fear that in this tempest of a world, I was what Césaire considered Ariel. Was my

reluctance to continue subscribing to Césaire and Fanon’s vision of violence as being

inevitable in the struggle against colonisation a sign of theoretical revision on my part,

based on my revolutionary experience?” The protagonist and the characters around

him are as willing to theorise themselves as they are to get high or point a gun, and

often these three actions happen in concert. The result is a didactic presentation of

thugs, addicts and hustlers as salon-grade thinkers and revolutionary polemicists,

with the Sympathizer commanding a pre-eminent position as a hyper-literate, hyper

self-aware insider-outsider — whether in France, Vietnam or the US.

With both sneering pride and withering self-deprecation, the Sympathizer

compulsively reminds us “that the Eastern and Western Hemispheres of my divided

brains remained joined in my head”, but for reasons that have more to do with

performing the evidence than decisively inflecting the shape of the story. Indeed, at

the novel’s startling climax, the demands of loyalty, sacrifice and life-and-death

decision-making among three men who have suffered together across war, migrancy

and three continents, give way to sharp-worded, slack-feeling invocations of Adorno

and Horkheimer.

Unlike its demanding predecessor — idea-filled and irreducibly searching in its mood

and effects — The Committed is a work of assuredly settled and excessively well demonstrated points. Its rawness and ideated rage make it easy to admire and perfect

to study, a bravura impersonation of a major novel.