In celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Viet Thanh Nguyen is in conversation with Professor Sheela Jane Menon for the Midtown Scholar Bookstore.

Read the full transcript below.

Alex: And oops I forgot my notes. And we are now live on Zoom. Okay, good evening, everyone. Welcome to the Midtown Scholar Bookstore’s Virtual Event series. My name is Alex. I’m with the Scholar, and as always, I am live in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania at the bookstore. Thank you for tuning in this evening as we welcome Viet Thanh Nguyen to Virtual Harrisburg. We’re delighted everyone could tune in this evening for this program. So thank you for supporting literature. Thank you for supporting the bookstore, and we hope you enjoy the program.

Alex: Now, tonight is special for more than a couple reasons. Viet spent some of this childhood in Harrisburg, which we’ll certainly talk about tonight. Of course, he’s written this powerful new novel, The Committed, but also because it’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, and we’re thrilled to be partnering for the very first time with the Pennsylvania governor’s Advisory Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs, and to that end, I’d like to introduce you to a couple of representatives that we have on screen with us this evening. Our interviewer this evening is going to be Sheela Jane Menon.

Alex: Sheela Jane is Assistant Professor of English at Dickinson college. Her research focuses on race and multiculturalism in Malaysian literature, and is informed by her upbringing in Malaysia, Singapore, and Honolulu. Her current book project analyzes a new cultural archive from Malaysia consisting of indigenous oral histories, as well as text and performances by Malay, Chinese, and Indian artists. Her work has been published in Aerial, Verge, The Diplomat, New Mandala, and The Conversation. Sheela Jane also serves as chair of the School’s That Teach Committee for Governor Wolf’s Advisory Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs.

Alex: And our other representative that we have with us here this evening is Dr. Nalini Krishnankutty. Nalini is a first generation immigrant American and a chemical engineer turned writer, educator, and speaker, who shapes narratives to empower immigrant communities through her writings, workshops, and talks. Her TEDxPSU talk on How Immigrants Shape(d) the United States is used in classrooms and workplaces across the country for education and training. She currently serves on governor Wolf’s Advisory Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs, where she co-chairs the Communication and Engagement Task Force.

Alex: So last thing before I hand off to Nalini, and that is we here at the bookstore would like everyone to come away with not just The Committed here, but both of these fantastic novels, and so we’re running a discounted book bundle. If you purchase both, it’s only $40, limited time deal. We’re running it through this weekend. So please place your order on our website, Midtownscholar.com or look in the chatroom in just a moment, where I’ll provide a link for you. And final, final thing before I hand it off, we’re reopening our doors for the first time this weekend in over 14 months, Friday and Saturday 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM. We would love to see you there. That’s it. But now I’m happy to hand it off to Dr. Nalini Krishnankutty.

Nalini Krishnankutty: Thank you so much, Alex. I’m so happy to be joining all of you from State College, Pennsylvania. And as Alex mentioned, I serve on the Pennsylvania governor’s Advisory Commission on Asian Pacific American Affairs. The commission is dedicated to ensuring that our state government is accessible and accountable to the diverse Asian Pacific American communities in Pennsylvania. Our commissioners who come from different parts of the state are engaged in advocating for those of Asian Pacific Islander origin all year round.

Nalini Krishnankutty: In 2021, I’ve had the honor of leading the commission’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month Project Team. In a critical year, as many of us who are of Asian Pacific Islander origins struggled both because of the pandemic and the uptick of anti-Asian hate, our community came together to make this May special, using it to shine a light on our experiences, celebrating our resilience and joy, the diversity of our voices, our insights about the past and the present, and our hopes and action for the future. As part of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, we are particularly pleased to partner with Midtown Scholar Bookstore on today’s event.

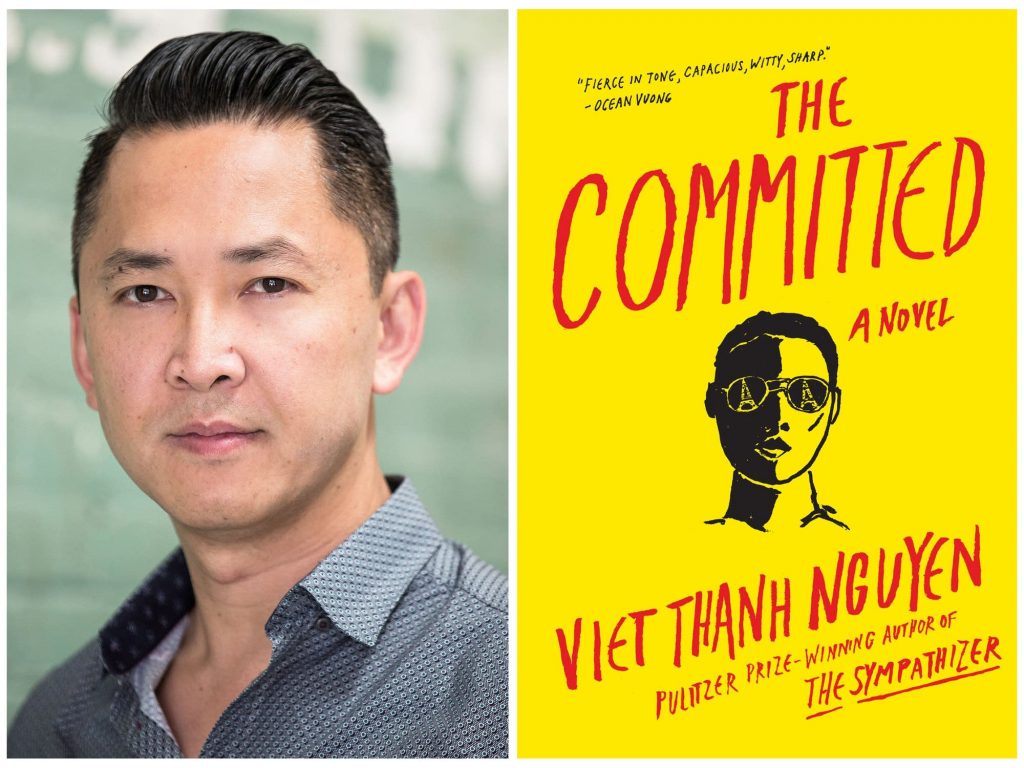

Nalini Krishnankutty: With that, it’s now my privilege to introduce our guest for the evening. Viet Thanh Nguyen born in Vietnam and raised in the United States of America. He’s the author of The Committed, the much awaited sequel to The Sympathizer, which was awarded the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in fiction, along with seven other prizes. He’s also the author of the short story collection, The Refugees, and the nonfiction book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. He’s the editor of The Displaced, which is an anthology of refugee writing.

Nalini Krishnankutty: He’s the Aerol Arnold Professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, and an award-winning teacher, researcher, and mentor to many. He’s a recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundations, and has written for the New York Times, The Guardian, The Atlantic, and many other venues. He lives in Los Angeles, and it gives me so much joy to welcome Viet Thanh Nguyen back home, even though it’s virtually, to both Pennsylvania and specifically to Harrisburg. [foreign language 00:05:31] Welcome.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Thank you so much, Nalini. It’s such a pleasure to be here virtually in Harrisburg. I really wish I could be here in person with you, and with Sheela Jane, and at the Midtown Scholar Bookstore. Obviously, just fabulous that it’s going to be opening up again. Go out there, support the bookstore, buy books from them, just show up, and show them some love for what they do. Hey, I did grow up for a few years in Harrisburg. We’re going to talk about that, from 1975 to 1978. I left probably I think right before the Three Mile Island nuclear meltdown, just one episode in a long episode of me getting away from fatal danger, and so maybe that gave me some kind of impetus for writing the novels that I’ve written.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So I’m here to talk to you tonight about The Committed. It’s a novel that’s the sequel to The Sympathizer, and for those of you who haven’t read The Sympathizer, shame on you, but you don’t really need to. The Committed is written to stand on its own, but I do want to give you just a very brief summary anyway of The Sympathizer, just encourage you to read it, if you haven’t read it yet. But The Sympathizer is about a part Vietnamese part French spy, and as we learn from the very first lines of the novel, he’s a man of two minds, and his one talent is to see every issue from both sides.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And the novel is written as a tragic comedy, which is a tone that continues into The Committed, and is a tragedy in that it follows what the philosopher Hegel had to say about tragedy. For Hegel tragedy was not the conflict between right versus wrong, but instead conflict between right versus right, and that’s exactly what happens in The Sympathizer, where our narrator is caught in all kinds of intractable, moral, political, ethical situations involving this conflict of right versus right.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And it’s a comedy also, because regardless of how much tragedy we’re dealing with, there’s always something funny to be found, at least in my opinion. If you go back to Shakespeare, for example, no matter how serious Shakespeare got, he always managed to put in some comic relief. There’s quite a bit of comic relief in both The Sympathizer and The Committed, because these novels are dealing with a lot of absurdities and hypocrisies. And just to give you a flavor, so to speak, of the comedy in The Sympathizer, there is an episode in which our teenage narrator loses his virginity to a squid, which is partly autobiographical.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’m not going to tell you which part of it is autobiographical, but this is what I think of as high literature, right? I mean, there is about 1% of readers, according to Goodreads.com and Amazon.com who find this absolutely revolting, and can refuse to continue reading past page 80 or so when that episode appears. That’s their loss. I think of it as high literature though, because it’s very clearly an allusion to Philip Roth’s novel, Portnoy’s Complaint, which I read at a very young age, and in Portnoy’s Complaint, young Alex Portnoy is so horny that he just has to masturbate with everything that he can find, including a slab of liver from the family fridge, which after he has done his deed, he puts back into the fridge for the family to eat later that night. And I think the most shocking part of that episode is that the family is eating liver. Who does that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So I succeeded in offending people with this squid episode, and in fact, the entire point of The Sympathizer was to try to offend everybody, Americans, pro-communist Vietnamese, anti-communist Vietnamese, because the novel is set during the Vietnam War and its aftermath, and judging from my hate mail, I succeeded in offending everybody. And so with The Committed, the challenge in terms of writing a sequel was who else is there left to offend? And clearly, the answer is, “The French.” Remember, he’s part French.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So the novel is set in Paris of 1982, and he has gone to Paris in order to investigate his French heritage, and I think I might be taking something of a risky move here, because the French actually loved The Sympathizer. They gave it some book prizes, and the French have a sort of this love-hate relationship with the United States. And so, of course, they’re more inclined to like novels that make fun of Americans, but this novel makes fun of the French. So I wonder how they will react once the French translation is published this fall.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And if you’re reading the news about France, they’re going through some issues right now. They have a lot of contemporary crises over the issue of race, and religion, and national identity, and culture, and guess what? They’re blaming Americans for exporting our ideas about feminism, about multiculturalism, and identity politics, and so-called cancel culture to France. So reading The Sympathizer and The Committed I think will be for you an education into contemporary or comparative racial relations, and the different ways by which the French and the Americans have tried to cope with their equally conflicted histories of racism.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: On one hand, we have American multicultural democracy. On the other hand, we have French universalism, this idea that anybody can be French if they just want to be French. So if you can’t be French, it’s not the problem of the French, or the French state, or anything like that, it’s your problem. I think that’s the dominant French attitude, and which is up for satire in The Committed, but I think the point in these two novels is not to say that one way is better than the other way, the French way or the American way, but to point out that neither of these wonderful systems of American multicultural democracy or French universalism can succeed in bringing us into a future of equality, and Liberty, and democracy, and so on without addressing the fundamental and foundational sins of both countries in terms of slavery, genocide, colonization, all that uncomfortable stuff that people don’t want to talk about.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And as long as you don’t talk about it, and as long as you don’t talk about it, and don’t engage in material ways of trying to remedy these inequities and their legacies into our present, we’re not actually going to achieve what either system promises can be done. So he gets to Paris, and the novel picks up exactly… Or how does he get to Paris? The novel picks up exactly where The Sympathizer ends off, and at the end of The Sympathizer, to make a long story short, he has gone back to Vietnam with a suicide squad to try to stimulate a revolution against communist in Vietnam. He fails, obviously, and then he flees the country again on a refugee boat, and this is where The Committed starts. I’m just going to read you a brief bit from the prologue of the novel.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: “We, the unwanted, wanted so much. We wanted food, water, and parasols, although umbrellas would be fine. We wanted clean clothes, baths, and toilets, even of the squatting kind, since squatting [inaudible 00:12:53] during the hot day and warmer during the freezing night. We wanted an estimated time of arrival. We wanted not to be dead on arrival. We wanted to be rescued from being barbecued by the unrelenting sun. We wanted television, movies, music, anything with which to pass the time. We wanted love, peace, and justice, except for our enemies, whom we wanted to burn in hell, preferably for eternity.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: We wanted independence and freedom, except for the communists, who should all be sent to reeducation, preferably for life. We wanted benevolent leaders who represented the people, by which we meant us and not them, whoever they were. We wanted to live in a society of equality. Although, if we had to settle for owning more than our neighbor, that would be fine. We wanted a revolution that would overturn the revolution we had just lived through. In sum, we wanted to want for nothing. What we most certainly did not want was a storm, and yet that was what we got on the seventh day. The faithful once more cried out, “God help us.” The non faithful cried out, ‘God, you bastard.’ Faithful or unfaithful, there was no way to avoid the storm, dominating the horizon and searching closer and closer.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Whipped into a frenzy the wind gained momentum, and as the waves grew, our arc gained speed and altitude. Lightning illuminated the dark furrows of the storm clouds and thunder overwhelmed our collective groan. A torrent of rain exploded on us, and as the waves propelled our vessel ever higher, the faithful prayed and the unfaithful cursed, but both wept. Then our arc reached its peak, and for an eternal moment, perched on the snow capped crest of a watery precipice. Looking down on that deep wine colored valley awaiting us, we were certain of two things. The first was that we were absolutely going to die, and the second was that we would almost certainly live. Yes, we were sure of it. We will live. And then we plunged howling into the abyss.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So why start the novel this way? When I was writing it, I was very much thinking of the refugee crisis that we’re living through now, as much as I was thinking about the refugee crisis that Vietnamese refugees were enduring in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And this is a time period that I think many people do remember, because the images of the Vietnamese people on boats trying to flee Vietnam were sent all over the world in photographs and so on. And I thought that that would be a really important experience to write about, especially in light of how in the last few years, the United States had been backing away from its longstanding commitment to immigrants and to refugees.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: We seem to be living through a period of America’s doors closing on people trying to come into this country, and so it was urgent to try to connect the past to the present. And another reason I wanted to write the book, write the opening in this fashion, was that I was trying to contest the way that Vietnamese refugees had been remembered, and the way that contemporary refugees were being discussed. And if you remember in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the name that the media had given to these refugees, these Vietnamese refugees, was, “The boat people.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And it was a very powerful term, because it helped to convince a lot of countries that it was their moral duty to absorb or to welcome Vietnamese refugees, and so now you have a diaspora of about 4 million refugees scattered all over the world, but it’s also a term that I think fixes an image of refugees in people’s minds, non refugee minds, as being desperate, and frightened, and pathetic. Now, there were certainly desperate and frightened. You would be too, but I don’t think they were pathetic. I think they were heroic, because they knew how dangerous this journey was going to be. And at a certain point, probably a lot of them knew that their chances of dying were pretty good, because tens of thousands of people disappeared on the open seas, and they did not survive the trip.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so when I look at refugees today trying to cross a river, or trying to cross an ocean on these rafts, and so on, I see that they’re being depicted in really negative ways, even by people who are sympathetic to them, turning them into objects of pity, if not contempt. And I can’t help but think that this is wrong, because these people are equally heroic, because they know as well that they’re risking their lives. And setting this novel in Paris and in France during this time was interesting, because I discovered that the French, who object to importing any kind of English words into their language, simply call the boat people, “Le boat people,” which is deeply problematic, right?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so I want to make sure that we understand them to be heroes, which doesn’t mean that they’re angels, simply that in this one dimension of their lives, they undertook something deeply heroic, which is why the opening of the novel cast them as people who are undergoing an epic journey on an arc, not on a boat. So they get to Paris, it’s 1982. Our Sympathizer ends up living with his aunt, who is also Eurasian, part French, part Vietnamese. She’s an intellectual, and through her, he meets the world of the French left, and the world of French intellectuals. That’s one of the two worlds he’s going to live in.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: The other world that he lives in is the world of the man he finds a job with, a crime boss, ethnic Chinese descent, who I imaginatively call, “The Boss.” And it’s through the Boss that we get immersed into the underworld of crime, and drugs, and continuing anti-communism, because so many of the Vietnamese refugees who came to Paris after 1975 were deeply anti communist. And I wanted to get the details right, so when I was in Paris doing research, I talked to as many French people of Vietnamese descent as I could. And I told them, “Hey, I’m writing this book about gangster life in Paris.” And uniformly these French people of Vietnamese descent said, “No, we don’t do that kind of thing.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Which is weird to me, because we Vietnamese Americans do do that kind of thing. There was a lot of gangsterism in Vietnamese American life when I was growing up. So then I thought about it, and I said, “I’m going to change the Boss and his gang into being ethnic Chinese.” And I went back to my interviewees, and they said, “Yeah, the Chinese would do this sort of thing.” So our narrator, because he’s been deeply traumatized by the events of The Sympathizer, makes bad choices, and he become what we would call a drug dealer, but that is a term that he wants to contest. I’ll read you this short passage. It’ll be the last thing I’ll read from the novel.

Viet Thanh Nguyen:

“Was I actually becoming that most horrid of criminals? No, not a drug dealer, which was a matter of bad taste. I mean, was I becoming a capitalist, which was a matter of bad morals, especially as the capitalist, unlike the drug dealer, would never recognize his bad morality or at least admit to it? A drug dealer was just a petty criminal who targeted individuals. And while he may or may not be ashamed of it, he usually recognized the illegality of his trade. But a capitalist was a legalized criminal who targeted thousands, if not millions, and felt no shame for his plunder.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen:I wasn’t and thinking about this at the time, but the best example we have of this is the Sackler family, a very nice white family I’m sure, making billions off of selling opioids to the American people and killing literally tens of thousands of people. But I think most people would not be afraid of walking into a room with the Sacklers, but they would be afraid of talking to a black boy on the corner of the street when their lives are much more in danger from this nice white family. And that is partly what The Committed deals with, this history of the French using drug dealing to finance their empire in Indochina.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I mean the original drug runners of the world were not people of color, were not Mexicans, or anything like that. The original drug runners in this world were their British and French empires using drug monopolies to finance their imperial efforts. Nice. So the committed is a thriller, just as much as The Sympathizer was a spy novel. In this case, it’s a thriller about crime, drugs, and violence. It’s also a satire of both right wing but especially left wing pretensions. I mean, a lot of people were mad about The Sympathizer, because they thought it was making too much fun of America, and capitalism, and American conservatism.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Here, I just want to demonstrate I’m an equal opportunity critic here. The French and the left wing get their share of satire. It’s very easy to do. There’s a lot of satire, and jokes to be made, and serious things to be said about French civilization, colonization, universalism, race, and so on. So I like to think of this novel as a thriller in terms of being both a crime novel and also a thriller of ideas. So I will leave you with the fact that our Sympathizer is a mixed race person. He is part French and part Vietnamese, but as he likes to tell us, he’s also 100% bastard. And as his mother has told him, he’s not half of anything, he’s twice of everything. Thank you.

Sheela Jane Menon: Thank you for that reading, Viet, and for framing your work, and for being with us tonight. As a Malaysian living in central PA, teaching Asian American literature at Dickinson College, it’s really such a joy to get to talk with you about your work today. I have to say, I’ve been teaching The Sympathizer since my very first year at Dickinson in 2016, and teaching that novel alongside your literary scholarship and your public essays has been truly such an enriching experience for me and for my students.

Sheela Jane Menon: And so, in fact, I want to give a special shout out. We have a Dickinson alum, Elaine Hang, tuning in tonight from California. She was an English major, and she wrote her senior thesis in spring 2019 on The Sympathizer. So your work has really meant a lot to us here in central PA. So thank you.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Thanks, Sheela Jane. I just want to point out, I did not know you were Malaysian until our meeting tonight, and I have to say that my editor for The Sympathizer, and The Committed, and all my works with Grove Atlantic is Peter Blackstock, who’s partly of Malaysian ancestry.

Sheela Jane Menon: Oh, [crosstalk 00:24:16].

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And he saved me, because The Sympathizer had been rejected by 13 out of 14 editors in New York City when we sent it out, and then Peter bought it, and I think the fact that Peter is English, number one, and then that he’s mixed race, number two, really helped him to understand The Sympathizer when so many other editors seem to be perplexed by it.

Sheela Jane Menon: Well, I’m really glad to hear that Malaysians all around the world are doing the right thing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Absolutely.

Sheela Jane Menon: In supporting and celebrating your work. So I’d like to open with a question about your ties to Harrisburg before we turn to The Committed. You referenced it in your opening remarks. I often assign your New York Times essay, The Hidden scars All Refugees Carry, and you talk about arriving in a refugee camp, the Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, 1975, and there’s a passing mention of Harrisburg. So I was wondering if you could tell us just a little bit about what you remember of your time in Harrisburg, and what are some of your memories of the city?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. My memories of Harrisburg were actually all really positive. We came in 1975 as refugees from the Vietnam War, ended up in Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, and then we were resettled, eventually, in Harrisburg itself. And we left in 1978 to go to San Jose, because we were cold. So there was that, plus there was better economic opportunities in San Jose for Vietnamese people. We already had a good family friend out there who had opened a Vietnamese grocery store.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: She said, “Come to San Jose.” And my parents did, and they opened perhaps the second Vietnamese grocery store a block away from first Vietnamese grocery store, which I can’t tell, is that friendship, or is that… What is that? Why did we do that? I have no idea.

Sheela Jane Menon: Collaboration, collaboration.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah, collaboration, right? Yeah. But in Harrisburg, what I remember is number one, I was four to seven years old when I was in Harrisburg, and I think, I have my son is seven years old. I’ve seen him grow up during the same period. And I think I’m convinced that children are very resilient, and they don’t notice necessarily what’s happening, and that is totally possible to have a great time as a kid, even if the circumstances may not be the best.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And for my parents, I think what was going on for them was that they’d been very successful people in Vietnam. They had been born poor, and then they worked their way up, built a fortune, lost a lot of it coming to the United States. And then we’re being seen as poor, desperate refugees in need of help, which they did need help, but they also were very resourceful people. And in Harrisburg, they didn’t have the opportunities to put those resources, their mental resources and so on, at play.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So they were working, basically, nine to five jobs. I think they started off as custodians, and then my dad started working for all of that typing machine factory or whatever, and my mom was unemployed, because she was a business woman, and she couldn’t do what she wanted to do. So that was a very major reason why we left for San Jose. So they were undergoing all these kinds of struggles, and I, obviously, was completely ignorant of that. And in fact, for me, it was a better time in my life than when we went to San Jose, because when we went to San Jose, my parents were working all the time at their grocery store, and had no time to spend with me.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Whereas in Pennsylvania, they were working nine to five, which meant they had time to spend with me. So I had pleasant memories of going on vacations, and having a birthday party. I would never have another birthday party again for the rest of my life after we left Harrisburg, and I just have fond memories of the snow, and of going to school, and making friends with the kids of I think mostly white, with a handful of us who were Vietnamese refugees. This was well before I was aware of anything like race, or racism, or anything like that. Maybe my perceptions would’ve changed if I had stayed in Harrisburg. I don’t know.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I have gone back to Harrisburg once about 10 years ago, drove through the city to see what it was like to try to find where we lived. And we lived in two homes in Harrisburg, and I went back to the… I found one of them, this sort of nice middle class, lower middle class house on a pleasant block and everything. I just had fond memories of that house, and ended up having fun there, and I am writing a nonfiction book, a memoir, and Harrisburg, we do start off with Harrisburg. So Harrisburg, you’re going to get your turn, done in my own fashion. I’m not sure people will like my rendition of Harrisburg, but we’ll see.

Sheela Jane Menon: Well, I think there are lots of folks in Harrisburg, and certainly Midtown Scholar, who would love to see you back in person, whether it’s for the memoir or for the sequel to The Committed. I’d like to turn then to the novel, and I want to start with a question that’s really simple on one level, it’s just about language, and it’s about one word, and maybe it seems obvious, but I was so struck by the way the word committed functions in this novel, and shifts, and changes as the plot moves forward in similar ways as The Sympathizer does in that novel. Right?

Sheela Jane Menon: And it seems like you play with every facet of the word. It’s verb, it’s noun, it’s adjective, it’s metaphor, it’s state of being, and it seems to be crucial for the way the narrator thinks through the big ideas he’s wrestling with. So I was wondering if you could talk to us a little bit about how you came to this word as such a vital component of both the plot, but also of the protagonist.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Hmm. Well, both these novels are deeply concerned with language. So on one hand, they’re supposed to function as entertainment, it’s crime novel, spy novel, thriller, all this kind of stuff, but myself as a reader and as a writer, I really enjoy works that pay close attention to language, and what it can do. So I didn’t want the language in either of these novels to be transparent, and that began with the titles of the novels themselves. In both The Sympathizer and The Committed, we have words that can have multiple implications.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so likewise, throughout the novel, there’s a lot of play with puns, and jokes, and wordplay in general, and all of that, and that’s partly just out of sheer fun on my part as a writer. I take pleasure in doing that, but also as we find out in The Sympathizer, he does some of things, and I was inspired by Nabokov and Lolita. The key line there is that never trust… A murderer will always have a fancy prose style, that’s a paraphrase of what Nabokov said, and so likewise, the language is a clue to the narrator himself and his mindset. Likewise, the language is a clue to my mindset as an author that part of my ambition is to write novels that are fun, and entertaining, and provocative, and all that, but also at the level of language to demonstrate that I got this.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I might be a refugee, and an Asian, and all that kind of stuff, but I got this language, and that’s part of the nature of making writing into fighting, as Muhammad Ali said. It’s not just the content, but it’s the very nature of our medium that is a tool and a weapon that needs to be deployed. So with The Committed as the title, obviously, there is the sense of being committed to a cause. There’s a sense of being committed as a writer. I identify my own writerly genealogy as stemming from writers who I see being committed not only to the art, but also to causes and to politics as well.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And then there’s the commitment that is an excess, that we can be over committed, and of course, if we’re too committed, we end up in an asylum. I’m not sure if that’s the right word to use, but the fact that the novel is set in France, which considers itself to be a country of asylum for refugees, is really crucial to where our narrator is eventually going to end up. And so one of the conundrums there is that commitment is not necessarily a good thing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I mean, it is technically a good thing on the surface, but what if you go too far? And I think that’s part of the ethical and political ambiguity that the novel explores, and it’s meaningful for me, because I like to think of myself as a committed writer, but committed to what? It’s very possible for people who are committed to go to far, and in the name of justice, and writing, or working against power, to themselves be committed to power, and to the abuses of power.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I mean, we’ve seen that over and over in history, and there’s a sense in which people who are committed to revolutionary causes can go too far, and the revolution tilts over from standing up for the oppressed and so on to murdering people, which has also happened on a very regular basis. And so the novel brings up for a while what happened in Cambodia, and what happened in Cambodia was that Cambodia sent its best students to Paris to study at the feet of the French, where they learned about democracy, liberty, equality, and so on, and then realized, obviously, that all these French ideals meant nothing, because in Cambodia, the French were not giving the Cambodians liberty, democracy, equality.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So these Cambodian students became the Khmer Rouge, and they just basically took French ideals and including European ideals like communism to total extreme. That’s commitment, and it’s also insanity that led to the death of a third of the population. Right? And so that historical dynamic, that political dynamic, which has defined my history coming out of Vietnam and out of Southeast Asia, is something that I’m obsessed about, and I wanted to try to delve into all of these complexities.

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah. And I think the idea of extremes and excess also shows up in the way the novel plays with, and critiques, and showcases colonial fantasies, right? About Vietnam, Vietnamese culture, and then also about Asians, and people of color more broadly. And I’m thinking here about in The Committed, we have, if I’m remembering correctly and counting correctly, three pivotal performances, right?

Sheela Jane Menon: You’ve got the orgy, the show, the Vietnamese cultural show, and Fantasia. And obviously, in The Sympathizer, we had the movie, right? With that illusion to Apocalypse Now and Platoon. And I kept being drawn in The Committed to the ways in which the novel engages the politics of representation, especially as I’m reading it in the middle of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, in the midst of this wave of anti-Asian racism. How did you conceive of these three performances in The Committed, and what choices did you debate, especially as you crafted the narrators place, and his role in each of those performances? Because they’re conflicted, and he’s deeply conflicted in each of them as well.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, one thing you have to know about the south Vietnamese people of which I’m a part is that we’re a fun loving people. We’ve been through a lot of terrible things in our history, but we always know how to have fun, and that’s actually a reputation in Vietnam the northerners, who are the revolutionaries, look at the southerners like, “Those are a bunch of lazy people. They just like to do the bare minimum work, and then they run off, and they have a smoke, and listen to music, and dance, and sing, and all that kind of stuff.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I mean, the northerners were so incensed by this that they called southern Vietnamese pop music, “Yellow music,” and they called the revolutionary music of the north, “Red music.” So I’m definitely a follower of the yellow music. Red music is mm-mm (negative), not for me. So we come to this country, and as refugees, and one of the first things we do is open a nightclub, which is what I talk about in The Sympathizer. And then we also then start our own song and dance show called Paris by Night, which is I believe in about it’s 130th episode right now.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so Fantasia in both The Sympathizer and The Committed is loosely inspired by Paris by Night, and so the narrator, I don’t think he has a love-hate relationship with pop culture. He basically loves pop culture. He has a love-hate relationship with the fact that revolutionaries with a serious problem look down on pop culture. And he’s like, “What’s wrong with this? Let’s have some fun.” And he deliberately says at some point towards the end of The Committed that revolutions that lose their sense of humor, revolutions that don’t allow you to have fun, and these are dangerous, dangerous revolutions.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So he’s all for performance, and spectacle, and all of that kind of thing, but he recognizes that there are ways in which these… So Fantasia is actually not problematic for him for the most part, right? What’s problematic are the variations of the spectacles. So one of them that you mentioned was the culture show. I’m not sure how many people in the audience have been to a culture show, but if you’re an Asian American college student in many university campus, you probably have seen or been involved with a culture show, where your task as a Vietnamese person or whatever is to put on once a year a song and dance show highlighting your Vietnamese culture.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And I sat through a few of these in college, and I thought after the third or fourth one, I was like, “This is boring.” And it’s like, “Is this Vietnamese culture? Because I don’t actually see any Vietnamese people doing these things outside of a culture show.” And by that I mean singing about courtship in a rice patty, or doing a fan dance, or whatever. And so the satire here is only the weak need to put on a culture show to prove what your culture is, because if you’re American or you’re French, you don’t put on a culture show. Your culture has already taken over the entire world through imperialism, basically.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So everybody has to deal with American culture and French culture, and American culture, obviously, is everything. It’s everything from George Washington, and the tricorne hat, and all that kind of stuff, all the way up to the Big Mac. That’s all American culture, but the weak who put on their culture show give us a very static version of culture that has nothing to do with present day reality. So if you go to Vietnam today, people are not doing fan dances, right?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I mean, Vietnamese culture to me is the dude with a Lamborghini on the streets of Saigon who cannot drive this car, which costs three times as much in Vietnam as it does here in the United States because of taxes. Cannot drive this car faster than 20 miles an hour, because the streets simply are too rough to do that. That’s Vietnamese culture. Why aren’t we talking about that instead? And then finally, the orgy. You gave it away. There is a big orgy at the end of the novel designed to offend more people.

Sheela Jane Menon: Sorry, I should have said, “Spoiler alert,” but I thought maybe orgy might be general enough to not give away too much.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. And I won’t give away all the details, but the orgy is a spectacle, and it is a spectacle that embodies, as you said, all the fantasies of French Orientalism, which are also pretty much the fantasies of American Orientalism too, except set in different countries. And part of what happens in The Commitment is that I wanted to satire not just politics, and ideologies, and all that, but patriarchy, and heterosexuality, and heteronormativity, because one of the things that became very clear to me at the end of The Sympathizer was that our narrator, and revolutions in general, and revolutionaries are very politically conscious in one sense when it comes to state struggle and things like that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And they’re totally politically unconscious in another sense when it comes to their own gender, and their sexuality, and the privileges that come with that. And so in The Committed, he’s forced to confront his own privileges as a heterosexual man, a Vietnamese man, and that he is not innocent of this kind of power in the same way that the French are not innocent of this kind of power when they stage this orgy, basically, for white men and women of color.

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah. And those shows then become moments through which the narrator comes to see, I think, those dynamics play out for others, and then for himself as he moves through them.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. Unfortunately for him it’s like, “I can’t enjoy this orgy.” He thinks because number one, I’m just too conflicted. I’m too aware of women now as human beings to enjoy an orgy anymore. Oh, poor him.

Sheela Jane Menon: Right. Well, so that brings me to my next question about reeducation. And again, I don’t want to give away too much. There’s a certain kind of reeducation that happens in The Sympathizer, but I was struck by how in The Committed there’s a self-guided process that the narrator seems to go through in sort of rethinking everything from masculinity and sexuality, as you just alluded to, but also what power, and freedom, and revolution mean to him. You’ve talked often about The Committed as a crime novel and a thriller, which of course it is, but the narrator’s transformation psychologically, intellectually also made me think of the Bildungsroman, right? That classic coming of age narrative. And I was just curious if to what extent you would consider The Committed a strange twist, or turning of its head of that coming of age genre?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Oh, yeah. Absolutely. I wrote a chapter on the Bildungsroman in my first academic book. So I know what you’re talking about, but it’s the whole idea of the Bildungsroman. I mean, not everybody in the audience knows what this is, but everybody has read one of these books, the coming of age story. Oftentimes, a coming age story of someone into a writerly consciousness. And as you said, strange and twisted, those are good adjectives for these two novels. Reeducation, it’s a bad name, right? Because reeducation in the Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodian context means it’s not about education. As survivors have said, it’s about forced labor and punishment.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so the reeducation that happens in The Committed is an actual process. Its not about forced labor and punishment. It’s about someone who’s actually rethinking everything that has shaped him and formed him, and about trying to educate himself again. Right? In a positive way. So in that sense, there is a reeducation taking place, as you’re saying, but not in the communist sense. So at the end of The Sympathizer, what we discover is that he’s a communist revolutionary and a spy, who’s been completely disabused of communism. He sees it for its failures and so on.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And typically, what happens in… And this is a whole sub genre of Western literature, communist who are disabused of communism. What happens typically is that they then embrace Western liberal individualism and democracy, and that’s not what I wanted to happen for our Sympathizer, but I didn’t… So I think that’s clear at the end of The Sympathizer, but the reason why I wrote the sequel is because I wanted to know what does a revolutionary in search of a revolution look like, and how does he rebuild himself or reeducate himself? And so that’s what The Committed does.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And in that sense, it is perhaps a Bildungsroman, but a late stage Bildungsroman. I mean, typically, the Bildungsroman takes place in your teenage years and so on. This is taking place when he is considerably older, but he’s gone back, and he’s thinking through these ideas about revolution, and violence, and justice, and so on from the vantage point of someone who’s seen the failures of some of these ideals, and he wants to ask himself, “So are these ideas still usable, and what would they look like in light of what he has learned from the first novel?”

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah. That’s great. Thank you for that. I was worried about asking the genre question, because I thought, “Well, does this just not make any sense?” But I’m glad to hear your response and your thoughts on that point. I’m going to ask one more question, and then we’ll switch over to audience questions. You referenced your first book, your scholarly monograph, Nothing Ever Dies, and I wanted to ask a question about the ghosts in The Sympathizer and The Committed.The narrator is certainly haunted by the ghosts, by what they represent of trauma, and guilt, and shame, and their voices really punctuate both novels, but become a chorus in The Committed, and I couldn’t help but think of the final lines of the introduction to Nothing Ever Dies.

Sheela Jane Menon: And if you’ll indulge me, I’m just going to quote two lines here for the audience, “Viet Thanh Nguyen writes, ‘Memory is haunted, not just by ghostly others, but by the horrors we have done, seen, and condoned, or by the unspeakable things from which we have profited. Haunted and haunting human and inhuman. War remains with us, and within us, impossible to forget, but difficult to remember.'” Could you talk to us about how you imagine these ghosts and their place in both novels, especially in light of how you think through memory and adjust memory in Nothing Ever Dies?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think that people who have lived through a war are inevitably haunted by ghosts in a figurative sense at the very least. People who they’ve killed, people who they’ve seen killed, people who were their friends or relatives that they’ve left behind, or lost in one way or another. It’s difficult to shake those ghost off. So I think for many people who’ve been through a war, especially if it was a bad war for them in whatever way, the war continues to haunt them.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And I’m speaking as someone who has no living memory of the… I don’t have any memory of the war in the sense that I left when I was four, but I was there during the fall of Saigon, for example. We were a part of that mass of people trying to get out, and I always felt growing up that the war was with me, that it had shaped my life in a very serious way, and that there was always these alternate universes out there where if my parents had made a different decision, my life would’ve turned out in a radically different way. What if we hadn’t been able to get out of the country, for example?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I grew up with my parents saying stuff like, “Hey, be glad you’re not in Vietnam, because if you were, you’d be drafted into the army, sent to Cambodia, and step on a landmine and die.” That was the kind of childhood story I would get from my parents, right? So that idea of an… And we had left my adopted sister behind. So it was a real thing that there could have been a total different branch of my life in a different direction. So I was haunted in that sense, and also haunted by the fact that the American culture is haunted by this history, that the Vietnamese refugee community was haunted by this history, that there were all these reminders of the war, and of trauma, and of loss, whether people were speaking about those things explicitly or not.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And of course, Vietnamese people do believe in ghosts, maybe Americans a little bit less so, but Vietnamese people do believe in ghosts, and in visitations, and all this. It’s alive, it’s a real part of Vietnamese culture. So in the novels, there is both a generalized sense of haunting of by the past, by the war, by trauma, and all its legacies, and then actual, real ghosts who appear in the novel. And of course, you can raise the question, “Are they really ghosts, or are they figments of the narrator’s guilty imagination?” These ghosts are people he has killed, or has had killed, or is somehow responsible for their deaths in various ways.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And I think it’s irrelevant in the end whether they are really ghosts, or just figments of his imaginations, all one and the same, but they embody, if that’s the right term, the sense that the past really is not passed, and that the people who are traumatized live with the past every day, and one of the definitions of trauma is that you have not escaped the past, and that the past can literally appear right before your eyes. And I think that’s a common narrative, a common story, that people who have been traumatized tell, that the scene of horror that traumatized them is always there ready to appear physically right before their eyes, and to encompass them completely. And so that’s what the ghosts do for our narrator and for the reader.

Sheela Jane Menon: Given how you talk about haunting there, and sort of the visceral nature of that haunting, or even of the comments your parents would make to you growing up, I think there’s a clear transition here to a question from the audience. This is from Dawn Morais. Full disclosure, Viet, this is my mother tuning in from Honolulu asking this question. She says she’s always been kind of astonished at the level of goodwill and admiration that some Vietnamese still have towards America, despite all of the trauma and the resentment after the debacle that was the Vietnam War, right? She’d like to know how do you explain that tension amongst that segment of the Vietnamese and Vietnamese American population?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, I mean, I think Americans who have gone to Vietnam or gone back to Vietnam have been uniformly surprised by the level of warmth that the Vietnamese people show them. I mean, this is a common refrain in stories from Americans who’ve gone and come back, because, obviously, Americans think that the Vietnamese will be angry still over the war. And I think that’s generally true that the Vietnamese have been willing to put the past behind them when it comes to Americans. Not true for all the Vietnamese. I mean, the Vietnamese are angry about it still, like the ones that they’re generally not running out to try to meet Americans, but for the Vietnamese that Americans are likely to come in contact with, either they’re in the tourist industry, or they’re the younger Vietnamese born after the end of the war, but it’s true even for some of the Vietnamese who lived through the war.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So there’s quite a few accounts of American veterans returning and meeting north Vietnamese veterans, for example, and engaging in peace and reconciliation in a private way. And so there’s a lot of combatants who are willing to put the past behind them as well. And I think that we have to understand that this is not true for Vietnamese and Vietnamese relationships. So the Vietnamese refugees, many of them of the older generation who lived through the war, are deeply afraid oftentimes of going back to Vietnam. They’re deeply skeptical of communists, and that verges onto hatred of communists, and likewise, the Vietnamese themselves I think have an ambivalent relationship to the overseas Vietnamese, a variety of different feelings.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think some Vietnamese, obviously, are not concerned about the past, but then there are other Vietnamese who do hold the past against the Vietnamese refugees who fled, either because they think of these refugees as traitors, as puppets of the old regime, or simply out of another set of complex feelings that these Vietnamese people escaped, and have lived these wonderful lives overseas, and while the Vietnamese who stayed behind had to endure decades of struggle, and poverty, and so on trying to rebuild the country. So it was a civil war, and Americans, for whatever role they played in it, were the outsiders.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Americans don’t understand this. Americans are very self-centered people. It’s like, “It’s all about me.” Whereas for the Vietnamese people it’s like, “It’s all about me too.” And in that sense, the feelings that Vietnamese people have for each other are much more complicated and ambivalent. And of course, finally, China. The Vietnamese really dislike Chinese people, or they dislike the Chinese state. And so part of the complex politics that’s happening now is that Americans are no longer the danger. They’re no longer the threat. They represent instead the promise of capitalism and also of strategic alliance against China, who’s the real enemy, and has always been the real enemy, or at least the very ambivalent figure giant to the north of Vietnam. And so that’s the terrain into which Americans are walking. I think most Americans are not cognizant of this kind of complexity.

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah, absolutely. Your reference to China, we’ve got a question from someone posting anonymously, who’s hoping that the third part of the trilogy will be set in China, given the tensions that you’ve just described. Is there any chance of that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: No. I don’t think so. Probably because it’s enough to be in trouble with one communist state versus two communist states, and then number three… or not number three, but I want the third novel to return to the United States, so he can make amends and seek revenge. That’s the plan right now.

Sheela Jane Menon: So as we think about the trilogy, we’ve also got a question here from August, and they write, “Regarding your upcoming TV adaptation of The Sympathizer by A24, what are you hoping to achieve? What is a good benchmark for quality in the book to screen translation?” How would you respond to that?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: What I hope to achieve is a Lamborghini and a house in Malibu.

Sheela Jane Menon: On streets wide enough to drive your Lamborghini.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Right. Exactly. Yeah.

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Just kidding. It’s not about the money. It’s about the art. What I hope to achieve? Well, I mean, A24 is a great company. They’ve done some amazing work on TV with Ramy, for example, highly recommend that series. And I signed the contract while Park Chan-wook, the director, was signing his contract, and if you know Park Chan-wook’s work, you would know why I’m excited about it. He directed, among many movies, Oldboy, which was actually a big influence on The Sympathizer, both for its visual style and audacity, and also for its crazy storyline, which I’m not going to give away.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And he also directed the TV adaptation of Little Drummer girl, the John le Carré novel, which is really great miniseries, and The Handmaiden, which is this visual spectacle and a great story to boot. So I think he has the understanding of politics, of colonialism, of racism, and he has the visual style and the totally weird, creative mentality that I think makes him a fit for the weird world of The Sympathizer and The Committed. So I’m hoping that the TV adaptation will match visually what the novels do in a literary way. And for that, I need people who actually have a visual talent, which I don’t have.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So I think the challenge in transferring the novels to TV is to somehow take what is a literary style, and the novels really depend on their literary style, which cannot be rendered literally on screen, and find a way to translate that literary style into a visual style, which I think will have to be a style of excess and of… I don’t know what adjective I’m looking for, but it has to be very markedly unique, and that’s what I think Park Chan-wook will bring to it.

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah. Great. Shifting gears here from thinking about screen adaptations back to thinking about the generational and intergenerational tensions that your works speak to. We’ve got a question from [Thuy Nga Dong 00:54:24], and they ask, “What do you have to say to young Vietnamese and Vietnamese Americans that have to deal with generational trauma from their grandparents?” And you’ve alluded to some of that in our conversation today. “Some old Vietnamese Americans see young Vietnamese as the extension of the communist party. It’s not the fault of young generation. Of course, there are less tensions between young generations of Vietnamese and Vietnamese Americans, but tensions remain.”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: That’s a complicated question. Well, I mean, it’s a complicated question in the sense that I think that many Vietnamese people… I mean, Vietnamese Americans experience this generational tension, because the generations tend to be, it’s not an absolute, but they tend to be politically different. They have different communication styles, different cultural expectations, and so on. And so I don’t have any advice for you. Sorry, you’re on your own. We’re all on our own here trying to deal with difficult family dynamics.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’ve coped with it, and that’s all I can say about it is I’ve coped with it by living sort of two lives. I’m not sure that’s the best solution for everybody, but that was my solution. I made my parents happy. I lied to my parents. I think lying is not necessarily wrong. It’s what you do with it that really matters, but do my parents need to know, for example, that I’m an atheist? I mean, they’re deeply devout communist. If I came home… I mean not communist. Deeply devout Catholics. If I came home and said, “Hey, I’m an atheist,” it would totally destroy everything for them.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so there’s no need to be honest in that regard. So sometimes I think this is really crucial that we Vietnamese people have learned how to save each other’s feelings when necessary by withholding information, and it goes in both directions, right? So there’s sort of this delicate dance of mutual understanding that not everything needs to be known. And then I live my own life outside of that, and so I say all kinds of things that I think my parents would probably be horrified by in public, and either they don’t read it, because some of it has been translated into Vietnamese, and there’ve been profiles of me in Vietnamese. Either they don’t read it, or maybe they read it, and they don’t talk about it. You know what I’m saying?

Sheela Jane Menon: [crosstalk 00:56:38].

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah. And I don’t know what’s happening on their end. Maybe they actually do know that I’m an atheist, and they just don’t want to say. So I think we have to have culturally appropriate means of dealing with people, so that being forthright is not always the best way. Now, I think the question might allude to the fact that in the Trump era. There were some of these delicate maneuvers were blown up, because all of a sudden, some Vietnamese people had to confront that other Vietnamese people in their family or the communities had radically different political perspectives, and they had come out fully blown in public, or at least in the spaces of their own homes, where people saw each other as mutually repugnant for the political ideals that they had, or at least one side saw the other side as politically repugnant, because one side was being explicit, and the other side, usually the younger set, felt that they couldn’t say what they believed out loud.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I don’t know how to deal with it within the family. That’s so unique to every individual family, but I have to say that in the community, my attitude is that having a shared community and a shared culture is important, but when your principles diverge, you have to stick with your principles. So that’s why I’ve spoken out in public against Vietnamese American politics when I think they are too reactionary, too white supremacists, too anti-black, things like that. I don’t need to be friends with those Vietnamese people. We don’t have to be all in one community, alright?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Maybe when we go to have food. Okay. We share some common things, but outside of that, we fought a civil war in Vietnam. Why should we think that things will be all hunky-dory here in the United States? So part of I think maturing as a community is to recognize that we can speak out against our community when it’s doing something wrong.

Sheela Jane Menon: Yeah. And that’s also a process of pushing back against the idea that Asians, and Asian Americans, or Vietnamese, and Vietnamese Americans are supposed to function as a monolith here in the US. Right?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah, absolutely.

Sheela Jane Menon: Well, thank you, Viet, so much for your time, for this conversation this evening. I think Alex is going to come back on to wrap this up for us.

Alex: Just want to thank Viet and Sheela Jane for this wonderful conversation. Thank you to our audience members. We had some really wonderful questions tonight, so thank you everyone for tuning in. Thank you for submitting questions. I’ve got to plug the books one more time. We’ve got The Sympathizer, The Committed here. We’re offering a book bundle, $40 for both. You can look in the chat room, follow the link there, or simply head to our website, Midtownscholar.com. And one last reminder, this weekend, grand reopening. After 14 months, we’re reopening the store Friday, Saturday 10:00 AM to 6:00 PM. Please, please, please, come by and grab these books. We’re going to have them at the front counter, so you can buy them there as you check out. And as I always end our events, I just like to give it back to Viet, if you have any last words for audience members as we close.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, I want to thank Nalini and especially Sheela Jane for speaking to me tonight. That was a great conversation, Sheela Jane. Thanks for teaching my work. Alex, thanks for having me. All of you out there, it was hard for businesses to survive in this pandemic era. Now Midtown Scholar has made it all the way through, so go and show them some love. You don’t have to buy my book, just buy some books, whatever they are, from them, and I’ve actually been back in bookstores here in California. It’s a great experience to be roaming through the stacks, and picking up and fondling physical books. So I really, really recommend that you do that.

Alex: All right. Thanks, everyone. Have a good night.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Bye.