Viet Thanh Nguyen is in conversation with Thrity Umrigar about the creativity and creation of writing for Literary Cleveland’s “Inkubator.”

Watch the interview on Facebook or read the full transcript below.

Michelle Smith: Welcome everyone to Literary Cleveland’s free annual Inkubator writing conference. My name is Michelle Smith, pronoun she, her, hers, and I’m the programming associate at Literary Cleveland. And we’re so happy to have all of you joining us today for the panel creative risks with Viet Thanh Nguyen. We will get started in just a moment. But before we begin, I need you to do two things first. Please use the chat feature on Zoom to join in today’s conversation. We will have a good panel discussion today, but this event will be even better if you participate by adding your comments in the chat. While we get started here, we invite you to open the chat, make sure you are sending to all panelists and attendees, and let us know where you are coming from tonight.

Michelle Smith: Second, we will have time at the end of the panel for Q&A. If you’d like to ask a question, please use the Q&A button at the bottom of your screen. You can ask a question at any time, and you can also up vote other attendees questions so you can push them up higher on the list of questions to be asked. Thanks for your help.

Michelle Smith: Now, we would like to begin by recognizing that the land upon which we reside is the traditional homeland of the Lenape, Shawnee, Haida, Miami, Ottawa, Ojibwe, Potawatomi Iroquois and other Great Lake tribes. The City of Cleveland occupies land seated by 1,100 chiefs and warriors at the signing of the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. We also like to acknowledge the 28,000 native American people who call Northeast Ohio home today, our neighbors, coworkers, classmates, and community members who represent over 100 tribal nations. At Literary Cleveland, we know stories are powerful and that who tells the story and where the story begins has a profound impact on our world. Let us acknowledge our past and work together for a better future. We have the power to change our story. Now, to help kick things off, please welcome Lit Cleveland board member, Lisa Chiu.

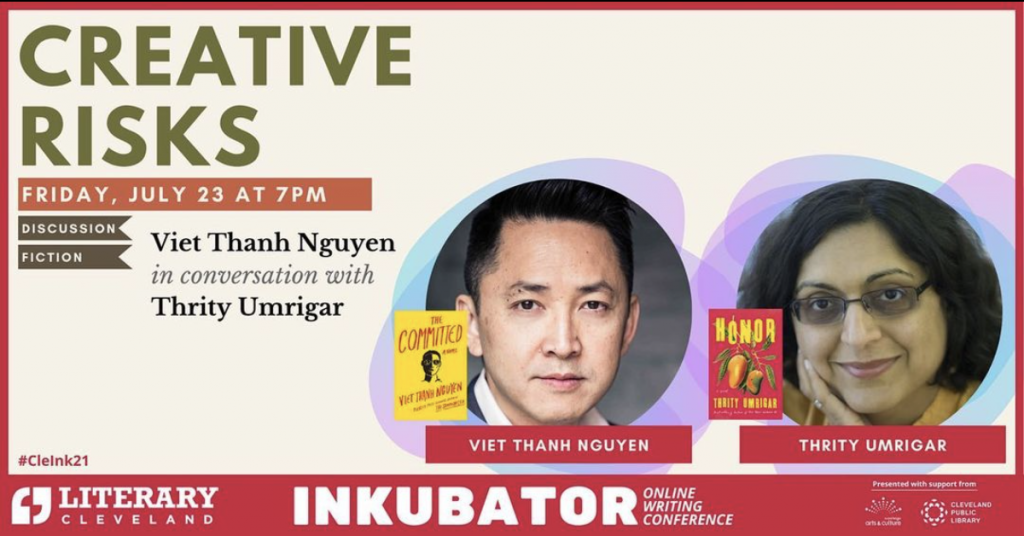

Lisa Chiu: Hi, everyone. Welcome, and thanks so much for joining us for the 2021 Inkubator Conference. My name is Lisa Chiu and my pronouns are she, her, hers. On behalf of the staff and board of directors of Literary Cleveland, I’d like to welcome you to the conference and to this session, creative risks with Viet Thanh Nguyen and Thrity Umrigar. I’m so excited about this event, which features two writers I deeply admire and I’m inspired by. I’m so happy they’re here today to share their wisdom and insight with us.

Lisa Chiu: Before we get started, I’d like to thank our sponsors. The Inkubator Conference is made possible by the residents of Cuyahoga County through a public grant from Cuyahoga Arts & Culture, and through support from Cleveland Public Library. The sponsor for today’s event is Loganberry Books. To support this free conference, please consider donating to Lit Cleveland or becoming a member. During the Inkubator only from now through July 25, that’s Sunday, we’re offering 15% discount on memberships. So head to the link in the chat to join or renew today.

Lisa Chiu: Now, I’d like to introduce our presenters for today’s event. Viet Thanh Nguyen is a writer, a professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity, and Comparative Literature at the University of Southern California. And the recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim and MacArthur Foundations. His novel, The Sympathizer, is a New York Times best seller and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. His newest book is The Committed, the sequel to The Sympathizer, was published in March. His other books are Nothing Ever Dies, Vietnam and the Memory of War, Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America, The Displaced: Refugee Writers On Refugee Lives and the bestselling short story collection, The Refugees. Recently, he published Chicken of the Sea, a children’s book written in collaboration with his six year old son, Allison. Welcome, Viet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Hi, Lisa. Thanks for that very kind introduction. Hi, everybody.

Lisa Chiu: And we have Thrity Umrigar. She’s the best-selling author of the novels Bombay Time, The Space Between Us, If Today Be Sweet, The Weight of Heaven, The World We Found, The Story Hour, Everybody’s Son and The Secrets Between Us. Her new novel, Honor, will be published in January 2022. She’s also the author of the memoir, First Darling of the Morning, and the children’s books: When I Carried You in My Belly, Sugar in Milk and Binny’s Diwali. Sugar in Milk just won the Ohioana Book Award in Juvenile Fiction. Thrity’s books have been translated into several languages and published in over 15 countries. Thrity is a distinguished university professor of English at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Welcome, Thrity Umrigar.

Thrity Umrigar: Hey, Lisa, great to see you. Hey, Viet.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Hi, Thrity.

Thrity Umrigar: Hi.

Lisa Chiu: Our moderator for tonight’s conversation is the executive director of Literary Cleveland, Matt Weinkam. Please, welcome Matt.

Matt Weinkam: Thank you, Lisa. Thanks, Michelle. And thanks to Viet and Thrity so much for being here tonight. We’re so excited about this event. I want to jump right in with this topic of creative risks by talking about the creative risk of creative writing. Both of you started your careers doing other types of writing, whether it was academic writing or journalism for many years. I think you were writing creatively in that time, but what is the risk of moving to this new genre of writing fiction? And Viet I’d love to start with you, because you had some articles recently in the times talking about… I’m thinking of the one talking about pursuing your dreams even if your parents may not always agree with that dream. And I know you’ve been writing creatively for a long time. But can you tell us a little bit about that move to writing short stories and then writing a novel and what their risk might be, not only career wise and maybe family wise, but also what’s so risky about fiction. It’s all made up. What makes it a creative risk?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Well, I think any kind of writing that you do has the potential be risky if you are trying to tell the truth, whether you’re trying to tell the truth through fiction or poetry or nonfiction. And so I started writing in college, but my first writing efforts were in non-fiction, the ones that first got published op-eds in the college newspaper. 30 years ago, I wrote an op-ed about Miss Saigon, which had just come out. And when you write about art and politics, you’re setting yourself up for people to hate you. So someone told me, “Oh yeah, the most popular English department professor at Berkeley hates your op-ed.” I was like, “Oh, okay, so I’m already making enemies at this young age?”

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And then 30 years later, Miss Saigon comes out again. I wrote another op-ed on Miss Saigon for the New York Times, and you do the hate nail that I got for daring to suggest that, that art could be racist. So there’s risks to be undertaken when you’re trying to do this non-fiction, political work. There’s risks to be taken when you’re writing non-fiction as a memoir. I’d love to hear about Thrity’s experiences writing her memoir, because I’m writing a memoir now. And it’s terrifying, because it’s not partly about revealing yourself, but you also involve other people like your family, my parents and things like this.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So I’m writing up that book today. I was writing that book today, and every day I just get freaked out, because I’m thinking there’s a lot of revelation taking place here, and I have no idea what people will think, because unlike with fiction, I can’t hide behind the idea that this is fictional. And then finally with fiction, the risk there, I think for me is that even though it’s not autobiographical, I invest so much of myself into fiction. It means a great deal to me. It’s my fantasy. It was always my fantasy to be a novelist. So there’s a huge bar there of potential failure that’s involved. And even though it’s fiction, there’s still a great degree of exposure, because you’re exposing to the world this creation that is so dear to you.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And in the case of something like The Sympathizer, I really felt like I was taking quite a big risk there writing something that honestly was meant to offend a lot of different people, but meant to offend, because I thought I was telling the truth about Vietnam, about the United States, about Vietnamese refugees, about the war in Vietnam. And honestly, I think when you do tell the truth about something controversial, inevitably, you’re going to offend people. And I think all of us as writers, we brace ourselves for that potential backlash to our work. But I think unless you take a risk, you’re not really going to produce something worthwhile.

Matt Weinkam: And Thrity, I know you spent… Was it 17 years as a journalist before your first published book? So what was that like, your movements into writing fiction?

Thrity Umrigar: Well, the reason I became a journalist in the first place and then leapfrog into what eventually became my career as a novelist is I grew up in India. My father had his own business. He had every expectation that I would run the family business someday. I had zero interest in doing that. I knew I was a writer really at a very, very young age. Even at that time in your life when you are uncertain just about everything, there was something deep within me that identified as a writer. I didn’t have the nerve to say that out loud, because the milieu that I grew up in, I would’ve been laughed out of town. But it was something that I knew down to my bones. And all through my teenage years, we were at loggerheads all the time.

Thrity Umrigar: And so journalism ironically was the least risky option I could take. It allowed me to wrap myself in a world of words. And yet none of the things that writing fiction is fraught with, for one thing, never earning a paycheck, somebody never publishing you. All that risk was minimized. So I feel like a bit of an imposter being on this panel about creative risk when actually I started my writing career by taking the easy way out. So anyway, I loved journalism. Matt, I came to this country for grad school when I was 21, and by 23, I was writing about school desegregation. After I got my grad degree, I got my first job and I was going into people’s homes. I was in some CEO’s office one day and interviewing somebody on welfare or spending time with a homeless person the next day.

Thrity Umrigar: It was an education about America that nothing else could have given me. There’s no university in the country that could have given me the education that I got within the first two weeks of starting as a journalist. So that was enough to sustain me for a long time. But that nagging voice of wanting to write, wanting to write after years and years of telling everybody else’s stories, wanting to say something, wanting to share with somebody else how I saw the world, that desire never quite went away. And certain opportunities presented themselves.

Thrity Umrigar: I was a little strategic in how I made that happen. While I was working full time as a journalist, I went ahead and went to school part time and earned a PhD in the worst possible way. I wouldn’t advice anybody to work full time and work part time on a PhD, but God knows how, but somehow I managed to do that. And because life was not complicated enough, I decided to write my first novel while I was doing these two things. Anyway, things worked out. And to be honest with you, writing fiction after years of being in the straitjacket of journalism, where it’s the whole truth, and hopefully nothing, but the truth, fiction felt liberating to me, because you could make stuff up.

Thrity Umrigar: And on one hand, there’s that element of making things up. But, of course, unless there is a core of truth in what you are saying, fiction collapses of its own weight. You have to have that foundation of truth before you can build a pretty edifice. So for me, yeah, writing fiction has risks, but it comes with a hell of a lot of opportunities also. And I just love flexing that creative muscle.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: If I could just add a brief addendum, I too took the safe way, which is because I became an English professor, and that is risky in its own right, but for me, it was the safe route compared to writing fiction. And it was really… What I’m trying to say here is you could try to just go all in on the risk, there’s no problem with that. That was not my style. I wanted to create a safe space from which I could take risks. And so there’s different ways in which I think people can take risks and manage risks. But the ultimate issue is at some point you need to be able to take a risk. And if you’re not able to take a risk at any point, then it might be difficult to be the writer that you want to be.

Thrity Umrigar: Yeah. I think that’s true. And since my assumption is that there are young people watching us, I do want to stress what Viet just said that you take risks, but you try and have some safety net if possible. There are people who just fly and they succeed. They take off and they succeed. And I’ve always thought there’s only two things that can happen when you take a risk. You either land on your face or you land on your feet. I’ve been extremely lucky in that I’ve landed on my feet.

Thrity Umrigar: When I left journalism, I didn’t leave it to take a tenure track position. That was created for me three years after I worked at Case as a visiting professor. I left a job that I had done for 17 years which I could do with both hands tied behind my back for a 10 month appointment with no guarantee that it would turn into anything else and no guarantee that I would be able to go on the job market and land something else. So that was a risk. There’s no question about it. On the other hand, I’d worked my butt off to get a PhD so that I had something that I knew would cushion the blow. So my advice to young people would be try and be strategic. Build enough of your life that when it comes time to jump, you jump and you fly.

Matt Weinkam: I love that both of you’re safe, not at all risky jobs are journalism and academia, which as people are putting out in the chat are themselves pretty risky. So I appreciate that. So that’s maybe the risk of getting into writing and especially writing fiction. But as you both alluded to, there’s the risk of what you choose to write about. And both of you don’t shy away from challenging convention or questioning power.

Matt Weinkam: Thrity, I’m thinking of the way that you’re tackling race and class with really complex characters in your novel. And I’m curious, does it feel like a risk as you’re writing it? Does it feel like these are going to be really tough thorny issues and I might get this wrong or I might offend someone? Does it feel like a risk as you’re writing? And what drives you to write about those subjects?

Thrity Umrigar: I’ll answer the last question first, because it’s the easiest. What drives me to write about these subjects is the desire to tell the truth. And if you have the desire to tell the truth in your fiction, if there’s no deceit, if there’s no taking into account critical reception or commercial success, which I try very hard, those things matter. I’m not for a moment denying that they do, but they cannot matter when you are working on that first and sixth and seventh draft. At that time, it’s the purity of the line. There has to be something pure in that act of creation, because if you don’t have that, honestly, there’s not much that you really do have. That mitigates the fear of taking a risk.

Thrity Umrigar: I’ve had books that have been shopped around where some editor has come and suggested a prettier ending, which knowing the Indian context as well as I do, I have to almost go like this, because I know how preposterous what they’re suggesting is doing. So what you do is you don’t pick that publisher for your book, because clearly there’s not a meeting of the minds there. The fear that I feel is about getting something wrong. That’s the journalist in me. I don’t want to get a date wrong, I don’t want to get a fact wrong, I don’t want to get what somebody might do in this situation wrong, I don’t want to get a thought in the character’s head wrong. And I certainly don’t want to get speech patterns wrong. And I write about people.

Thrity Umrigar: Even though I’m writing in the Indian context, this is something that American readers sometimes struggle to understand. I can be writing about India, but I might be writing about a character with whom I share very little other than the place of birth. Our circumstances might be completely different. So I have to be careful. It’s not just writing outside culture, it’s also within the culture, there’s so many, especially in a complicated country like India, there’s so much class difference, there’s so much linguistic difference. You have to be able to capture most of that. So that’s where the risk comes in. And it’s terrifying. And paradoxically, that’s why it’s so exciting to do, because it’s terrifying.

Matt Weinkam: Viet, does that speak to your experience? I think that your novels especially feel so fearless to me and I think you even mentioned earlier feeling like they might even be designed to offend in some respect. Do you gain the excitement from that, from the possibility that this might while some people up?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Yeah, because I think when it comes to risk taking and writing fiction doesn’t talk about that. I think there’s at least two ways that you could take risks. One is in content and one is in form. You could do them separately, you can do them together. In the novels, The Sympathizer and The Committed, there’s certainly a lot of content that I think is risky given the audiences that these books are addressed to.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So for Americans, I’m just going to talk about Americans. For The Sympathizer, Americans have a deep seated ideological belief system about themselves and the country called the American dream. Okay. And when it intersects with things that contradict the American dream, such as slavery or genocide or colonization or the war in Vietnam, a lot of Americans have a really hard time hearing these contradictions being put into play, especially from someone like me, who they anticipate should be grateful for being an American.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So to put forward content that foregrounds the failures of the United States from someone like me is automatically offensive to a substantial part of the American audience. So there’s some certain risk taking that’s taking place there. And there are penalties for that. Your book could not be published, for example, or your book could not be as hot of a commodity as it might otherwise be. And that is what happened to The Sympathizer. I’ve talked about this many times, but I’ll keep hammering it home. The book was rejected by 13 out of 14 publishers when we put it out there. And the person who bought it was not an American, was English and was of mixed race dissent. So someone who was not groomed with this American ideology.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Formally, there’s risk taking to be done too in a novel like The Sympathizer and in The Committed, for example, there are no quotation marks in these two novels. And apparently this offends a lot of people. I got so many comments, “Why are there no quotation marks in your fiction?” It’s not even that daring. People were doing this a century ago, for example, but in the American context, I think American readers on the average tend to be rather conservative and they don’t want a lot of formal risk taking in their fiction. But I felt that it was necessary. These kinds of formal decisions that I was making, I felt that they were related to the content. It’s a very involved discussion.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: But when it feels to me that it’s necessary to provoke the reader, both in content and in form, I will do it, because of otherwise I’m not that interested, I’m not that excited. There’s a lot of fiction out there that I think is very safe, very boring, very well done too and can be very fun to read. That’s not what I want to write. That’s not saying that it shouldn’t be written and that people shouldn’t read it, but for me, that’s not what I want to write.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And the last thing I’ll probably say here is that every writer has to have what the creative writers like to call a voice. You spend all your time learning how to be a writer, it’s a matter of art and craft, but it’s also a matter of finding whatever this voice happens to be. And one way of understanding that is that your voice is something that is innate to you, that you believe in. You could also talk about it as a vision as well. But whatever your voice and vision is, you have to find it. And then you have to believe in it and you have to commit to it, because if you can’t commit to it, you’re not going to be a very good artist. And if your voice and vision is like that of Steven Spielberg, congratulations, you’ll be rich. And if your voice and vision is like that of an avant garde artist, you’re not going to be rich, but you have to pursue whatever it is that is innate to you that you believe in.

Thrity Umrigar: Matt, I want to add something here on this topic of risk. And I think this pertains perhaps more so to writers of color and especially people like me who are writing about different cultures. And I did this book talk pre COVID, so let’s just call it 2018. And it was a typical liberal, white liberal, middle aged, predominantly female audience. It was a luncheon. And this rather elderly lady stood up very well healed you could tell, and she said, “I read your books about India and you’re describing gender discrimination, class discrimination, rape at times,” just all these things about Indian culture. And she said, “It makes me hate India.”

Thrity Umrigar: And I have to tell you that it threw me for a loop. I’m usually very good in these settings about coming back with something. And this truly gave me pause, because that is not what I’m trying to do in my books at all. I’m trying to describe my piece, my slice of a culture, and I’m trying to be true to the story. That is what’s important to me. I don’t hold myself up by any stretch of the imagination as somebody who’s a spokesperson for all of India, a country that’s three or four times the size of the United States in terms of population, 21 languages officially recognized in the constitution, very diverse society. I’m just telling one story pertaining to a finite set of characters.

Thrity Umrigar: And whatever I expected, if somebody had thrown a shoe at me, I could have of handled that, but this was hard, because I thought other than whatever I stuttered back to her, which is, well, one could say that just about any society. And we commonly read books about dysfunction in the United States. We are not judging entire cultures by individual stories. But since then, I have truly in my own writing, and as I’ve alluded to before, when I’m writing, I try very hard to block out the outside noise. This one sentence or two has somehow penetrated that wall. And I’m conscious of that in a way that I wasn’t for the first eight novels. And suddenly I am. And I’m trying to write against that and certainly not let that influence anything at all.

Thrity Umrigar: I suspect this is what African American writers have gone through in the past and go through now. Any anytime you’re writing something that is not part of the dominant culture, I suppose this is a risk that one takes also. I don’t know if this made any sense or if it even fit in with what our topic is, but I somehow feel like it does.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: You mentioned black writers, and I will never forget the story about Richard Wright. He wrote a book called Uncle Tom’s Children, which was very successful. And he recounts an anecdote where in the aftermath of that book, this white woman reader came up to him and said, “I cried so much reading Uncle Tom’s Children.” And Richard Wright was like, “I don’t want you to cry, that’s not the desired result of this book.” And he wrote Native Son as a result of doing that. And I think what that anecdote speaks to is precisely this idea that for dominant white readership, oftentimes when they look at people of color or any other so-called minority population, it’s a voyeuristic relationship of a spectacle. They want to see a spectacle of whatever kind and they want to feel pity to cry, to have this catharsis around that experience.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And I feel like that’s true also for Asians as objects, it’s true for the Vietnam War, where the Vietnamese in the American imagination are only rendered as objects of pity and as victims. And certainly that was of what I was reacting against by writing novels in which the Vietnamese main protagonist is not someone that you can cry about, because he is a very complicated human being as Americans are. And when we say complicated, we don’t mean objects of pity or just objects of sentiment, but people who are capable of doing good and bad. And so the reader who is speaking to you is totally wrong, you should get her out of your mind or use her as a positive example, because she’s exactly the reader you want to provoke. And if she ends up hating India, it’s not your problem, it’s her problem.

Matt Weinkam: Yeah, Viet, if you want to dive a little bit further into that, I’m curious how you thought, especially maybe in The Committed about who your imagined reader was now that you’re adding a new place, a new state to the discussion of these books. You’re not only commenting on America and Vietnam, but also France now. And so how are you thinking about how these different readers might interact with the book? Did that change the way that you wrote it at all?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: When I was trying to be a writer, which also took me about 17 years, I think before I could really feel comfortable calling myself a writer, I wrote with a lot of readers in mind, what would the Vietnamese American community think? What would editors, agents, publishers think, people who can make my reputation and all of that? And it’s a very bad mental state to be in when you’re thinking about readers like that. So when it came time to write The Sympathizer, I decided I’m going to write for myself, which is something your agent and your editor probably don’t want to hear, because they want to hear that you’re writing for a million people and not one person. But it was enormously liberating to do that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And when it came from The Committed, and this is in response to Maya’s question in the chat, The Sympathizer won the Pulitzer Prize and she asked, “Was that liberating or was that suffocating to have this prize in terms of writing a second novel?” And for me, it was liberating, because I felt, well, I don’t need to win another Pulitzer Prize, what else do I have to prove? And I thought I’m going to write The Committed just as I wrote The Sympathizer for me, because The Committed, I think, takes even more risks than The Sympathizer does, formally speaking. And also it takes risks because I’m writing about France and I’m writing about… It’s a novel set in France, and the French are very judgemental and easily offended. And here I am an outsider, a formerly colonized person coming in writing about France and saying a lot of satirical things about France.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And I thought that the French are my second audience after me, but I can’t worry too much about what they think, because again, I think I know enough about the French to say something about them. The French will have lots of things to say about Americans, even though the French are not Americans, so why can’t I say something about the French given that they colonized Vietnam and I’m an indirect product of that colonization? So in writing for myself, I think there’s a degree of defiance that’s involved, again, because I don’t care what that white woman in Thrity’s example thinks of the story. I don’t really care what the French think of this story. If they love it, that’s great. If they hate it, that’s also fine. And I’m going to go to France in November for the French edition of the novel. So I will find out what the French think about this book.

Matt Weinkam: I want to return back to what you were saying about the other form of risk is not just the content of what you write, but the way that you write it and some of the formal risks that you might be taking. And both of you are doing that, I think, especially in perspective and how you write point of view and how you write tense. And maybe I’ll start again with you, Viet, but that’s especially now in The Committed, the use of the first and second person and the collective. We’re a writing organization, this is a writing conference, and so we can nerd out about point of view and formal risks now, but can you talk a little bit about that an outgrowth of the first book, and I think you’re deepening it in the second one. How do you see that working in the text? Was that something that was exciting to you? How was the formal language on the page interacting with some of the thematic work that’s happening in the book too?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I don’t know how the writers write, but for me, there’s a relationship between the rational mind and the theory that I’m thinking about in my awareness of literary history, in my conscious mapping out of plot and theme and structure and all of that. And then the other side, which is the unconscious part, the intuitive part that I really can’t explain. And these things are in interaction, for me. So in writing The Committed, for example, I had a 50 page outline and dense notes about the various kinds of concepts I wanted to bring in. But at the same time, once I started writing the book, I also let the feeling of writing the book carry me along. So if it felt like I wanted to switch to the second person, I did, or if it felt like I should write a six page sentence, I did. So it just felt right. It felt good.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And I think part of what it means to be a writer, accumulating years and years of experience is that it’s not that you exhaust your knowledge of the subject, but you become more confident in your capacity to take certain kinds of risks, you become more confident because you know yourself better as a writer. At least I did. And in my case, I also felt like I had accumulated knowledge about the literary works that I was referencing and that I was interacting with.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So I don’t think that The Committed necessarily does anything that is completely original in terms of form. I think most of the things that I did in that book, you can find in other works. So, for me, it became fun, because imagine that you have a bag of tricks and you know that the history of whatever discipline you’re in, it’s fun to be able to pull them out and to throw them around and to know that you’re responding to other writers. And it’s fun to know that readers who understand will also know the tricks that you’re performing. So that for me, I get a lot of joy out of that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So the intention behind the various kinds of formal devices is partly to provoke a certain political and aesthetic response, but it’s also just to have fun. So the last thing I’ll say is in terms of provoking a political and aesthetic risk response, for example, the book, as you said, Matt, switches between first person, second person, first person plural, and part of what’s happening there is my thinking that this narrator of The Committed is having a total breakdown. If you read the book, you realize this guy is not totally healthy when it comes to his mental state for a very good reason. And because we’re inhabiting his point of view, I have to describe that in some way, but I can’t have him come out and say, “Hey, I have post traumatic stress disorder,” because that term didn’t exist for him. And I can’t write about this as if there’s a third person narrator looking at him describing his mental breakdown. So formally I have to find some way to convey his disintegration. And the shift of various kinds of pronouns is one way of doing that.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And finally, there’s a tension in these novels, The Sympathizer and The Committed, between the individual and the collective. And we as Americans, come from a society that really privileges the individual, but he’s a revolutionary and he’s also very conscious of the collective. And so the turn towards you and the first person plural are gestures towards that collective identity.

Matt Weinkam: Thrity, I think you could have it in a little bit different way by having usually either multiple points of view and creating these really complex characters that interact that we feel like a great deal with sympathy for. And so we’re not really grounded in the same way that you are with just a single first person narrator. And so we end up feeling a lot more complex about the whole situation, because we have these different point of views. And I think that’s across many of your books. Is that something that you see? Again, is it fun to grade multiple care? How do you approach that formal element as you’re drafting novel?

Thrity Umrigar: I think I’ll go back to what Viet said about some part of writing is just instinct. It’s how the book comes to you, how it presents itself to you. And I try very hard not to impose my writer’s will on a book, on the subject matter. It has to feel organic, it has to rise from the book itself. And, for instance, I have a book called The World We Found, which tells the story of four women who are political activists in India when they were in college in the 1970s. And then we take this giant leap of time, and then we meet them in their lives today. But a lot of the plot. So it made perfect sense to tell the story from at least all of their points of view.

Thrity Umrigar: But one of them has a husband who’s very involved in this. He’s a fellow activist. And he’s the one in some ways… Well, he’s one of the two male characters who have changed very much over the years. This guy has gone on to becoming a very successful businessman, turning his back a little bit on his left, his past, all of that. So fairness demanded that we hear from him. And so initially in the first draft or so, I only had those five characters, but then there was Iqbal, who’s this Muslim guy who was one of the group in the 70s, and he has found religion and he has become conservative over the years. And he becomes his resistance to what is happening in the current plot, plays a huge role in propelling the plot. And yet in the first draft, I didn’t give him a voice.

Thrity Umrigar: And after I finished the book, it became really obvious to me that just for simple reasons of fair play, Iqbal, should get to make his own case directly to the reader. I think he’s only in two chapters, but he speaks directly to us. And I think it made all the difference in the work. It just became a stronger book, because the writer, me, was respectful enough to a character and decided that he shouldn’t be object, he should be subject, that he should have agency in explaining to us why and what circumstances have made him change in the way he has.

Thrity Umrigar: The book called The Secrets Between Us, which is the sequel to the space between us, I wanted to quickly describe the misery of being a vegetable vendor in an open air marketplace, just in time for the monsoons. And instead of yammering on and on about it and writing five chapters on it, I just decided to have a little bit of fun. And I think it’s just a two page chapter with no punctuation. And it’s like this stream of consciousness that starts with because, basically because life was not miserable enough, because blah, blah, blah, because blah, blah, blah, the rains have arrived. And that’s how the chapter ends. I didn’t plot that in advance. I didn’t map that out. It was just when my hands were on the keyboard and I was there, it just poured out of me in that way. And I decided it held up. So I kept it in.

Matt Weinkam: Yeah. It reminds me a lot of Toni Morrison who feels like you can sense that her empathy just extends in all directions and that she just gets interested in a character and wants to hear from them. And so it’s not mathematical how we’re jumping. She’s just following these people that she has grown to care for too. And I think there’s a similarity there.

Matt Weinkam: I do want to shift gears just a little bit to talking about not only your fiction, but your writing, especially online. What I love about both of you as writers is that, especially in the last four years, you didn’t shy away from using social media tools to not only speak out as writers, but as activists as well. And I’m curious to hear you articulate what that experience is like and where the drive is like, what the response is, because it’s for sure a different mode and medium. It’s a still very new form of writing and engaging. It’s also so one in which you’re going to get immediate feedback from a mass group and that can involve all the negative bio that can come up on social media too.

Matt Weinkam: And I’m just curious how it fits into your practice, both as writers and as people in the world challenging authority in the way that you have in your writing. How that works when you’re doing it on social media. And I think I just want to add in one element here, which is, we’re talking about the creative risks in this conversation so far about doing something, about writing, about the kinds of things you write about, the way you write about it. But maybe I think what this activism might get at is what is the risk of not doing something, of not speaking up? And so maybe I’ll start with you, Viet, how do you see that role online?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’m very ambivalent. You mentioned Toni Morrison. And sometimes I ask myself, “Would Toni Morrison be on Twitter?” Probably not. She’s more sensible and wiser than to do something like that. So it’s a very ambivalent relationship to social media. And I think most of us have that ambivalent relationship. Obviously, you accumulate followers on your various platforms and then you realize that you can make some impact, but I really don’t know what impact. So what if 100,000 people like my tweet, it happens once in a while that, that will take place? Have I changed anybody’s minds? Am I convincing? Are there people to convince? Who knows? And in the meantime, what’s happening to me, I’m getting that stupid dopamine rush from think, “Oh my God! 100,000 people like the tweet.” But then the reverse is also true, if I put my foot in my mouth on Twitter, and everybody does, I think eventually, the fact that people are hating me on Twitter, that doesn’t make me feel great either. Is it worth it to have this negative emotion to do the positive emotion?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so there’s always this balancing act between the political potential of social media and then the emotional downfall of social media as well. So, for example, I had a public Facebook page that reached 84,000 followers in the fall of 2020. And I used it to engage in a lot of battles with people around Trump and everything. And a lot of the Twitter followers were Vietnamese. And the amount of support for Donald Trump in the Vietnamese world, whether it’s Vietnamese Americans or the Vietnamese of Vietnam is fairly high. And so I think, before Trump, the Vietnamese tended to view me in a very positive way, because I brought home the Pulitzer for the Vietnamese race, even if they never read the novel. But then you bring politics into it, and then all of a sudden, there’s all these Vietnamese people and others who were hating on me, because I was saying very mean things about Donald Trump and his followers.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And so you eventually, I felt that I was being poisoned myself by this page. It was bringing out the dimension of me that I really didn’t like getting into all these fights with people and feeling like I needed to post every day something provocative or intelligent. And so I felt like after Donald Trump lost the election, that page served its purpose. And I detonated it and lost 84,000 Facebook followers. And for a few weeks, I was like, “How do I get my Facebook page back?” But thankfully I couldn’t. So I’m not wistful for that anymore.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So all I’m saying here is for most of us, I think who are writers, social media is generally speaking not a great thing. For people who are native only to social media, obviously, they can do some amazing things with it. You look at people of this social media generation, they could be 20 years old and they could have 100,000 or 200,000 Twitter followers. Whether that’s good or bad is up for debate. Every week, I wrestle with whether I should just terminate these social media profiles. The utility that I get out of them, for example, the op-ed that you mentioned about creative risks for the New York Times, I workshop that on Facebook. So there are some ways in which I draft ideas on social media, on Twitter, on Facebook that eventually become articles or parts of books. I just really don’t know if it’s worth it.

Thrity Umrigar: Matt, I’ll answer this by going back to what you said earlier about it’s not just the risk of participating, it’s the risk of not participating. And when I’m on social media, I’m not there as Thrity the writer, I’m there as Thrity the citizen, as Thrity the human who finds it very difficult to keep her mouth shut. So I don’t for a minute have the conceit that I’m changing anyone’s mind or heart on social media. Most of the time, I’m just talking to people who share the same politics that I do. And yet it feels necessary to me when something egregious happens to weigh in on that. It feels as necessary.

Thrity Umrigar: I might get myself in trouble with saying out loud what I’m thinking. But in some ways the motivation for writing books is akin to writing on social media. It’s having an opinion and trying to find a forum for it and not wanting to just keep it to myself. So it’s, of course, a difference in degrees, which perhaps makes a quantitative difference. But that’s just how I see it.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I’ll add one more little thing here. When I had those 84,000 followers and it was getting very controversial, I would have some older Vietnamese people. I’m sorry. People my age who are parents or people who like 20 years old, and they would tell me, “My children listen more to you than they do to me.” And I felt, wow, that gives you some sense of this power of social media. I’m not sure I want that, but at the same time, what Thrity is saying is absolutely right, that dimension of citizenship, this idea that there is a whole public discourse that’s taking play through social media that many people do take very seriously, that’s not to be shrugged off.

Thrity Umrigar: And I actually think that if Twitter had existed, say in 1979, Toni Morrison would’ve joined and she would’ve been on it. We are thinking of Toni Morrison as Toni Morrison in the last 20, 30 years. But as a young activist, I think she would’ve been on Twitter.

Matt Weinkam:

That’s some fun fiction to write. It’s worth some tweets. I had a bunch more questions, but I want to pull some from the Q&A now. And there’s one in there that’s about process that’s asking, I think maybe especially the beginning of your career when you’re an academic or a journalist or doing a PhD, and you’re finding time for writing creatively outside of the day job, how did you find time to decompress from that job and then also bring the creative self to the fore? And maybe I want to add one more which is, how do you stay motivated when it feels so good not to write? At the end of a day job, how did you push through to write those, especially first books?

Thrity Umrigar:

It never feels so good not to write. It always feels better to write than to not write no matter how tired you are, no matter how hungry you are, which is a word I just learned from my 26 year old niece and now I can’t stop using it. No matter what, it’s a stress reducer in some ways. It feels better to write than to not write. And look, this comes up in book talks during the audience Q&A all the time, somebody always stands up and says, “I have this story to tell, I have it in me, I just don’t have the time.” And I always say to them, “How many hours in a day do you have? 24. Guess what? I have 24 too. Nobody that I know of has 26 hours in their day.”

Thrity Umrigar: So it’s just a matter of priorities. And there’s this whole stuff of 80s, 90s, the 2000s television that I know nothing about, because when everybody else was sitting and watching, whatever, Friends and This Is Us and everything else, I was writing. So if you love something, you sacrifice for it. It’s true for the people in your life, it’s true for the work in your life. And it’s really ultimately that simple. Don’t want to get too carried away here. People have genuine barriers that don’t allow them to do it, but you know what? Most people, no matter what job you do, no matter how many… Toni Morrison had two children and was a well respected editor at Random House when she wrote her first three novels and the third one being Song of Solomon. She managed to do it. And I always remember that and I always remind myself of that, if Toni Morrison could do it, so can the rest of us.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: I think you’re a writer if you can’t not write. Okay. So what Thrity is saying is true for me, if I don’t write, I turn into a nasty human being. I feel bad. My wife feels bad, because I’m irritable with my family. So that’s a bad sign. And I think what happens is that the more you write, the more you become that person who can’t not write, because it becomes a part of you. And this question of when to find the time for writing, I think most of us who are writers have two jobs. The number of writers who are full time writers, who are wealthy enough or who have become successful enough that all they can do is write, that’s a very, very small percentage of writers. Most writers have to have two jobs.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And that was true for me. I had to become a professor and I had to write. And when did I write? I wrote when I was not professing. And yes, you pay a price for that. I’m in California. I could have spent all my time out in the sun having fun, but instead I was in my room when I was not teaching or grading writing. So if you can’t do that, then you’re not going to be a writer. We all have to make that choice. Now, the thing I would say here though, is that there is this… One of the common writing mantras is write every day. And I think that, that’s not possible for everybody, it wasn’t possible for me. But I think what is true is that you have to spend a certain number of hours writing in order to become good.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: You look at Olympic athletes, they spent ten thousands of hours becoming Olympic athletes. And no one would ever deny that they did that. You look at writers, it’s the same thing. So it doesn’t matter whether you do your thousands of hours in 10 years or in 40 years, but eventually you have to do those hours for 99% of us who are writers. The way 1% of writers who are natural born geniuses, I hate you, but the rest of us, we got to work.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And the last thing about the switching between being a journalist or a professor or being a writer, for me, the way I thought about it is that these are different languages. To become an academic, I had to learn a certain language. It took me a long time to do that. And to become a fiction writer, I had to learn that language. It took me a long time to do that. And it’s like becoming bilingual, you have to become fluent in both languages. It’s really hard. But when you do, the amazing thing is that when you can switch between the two languages or more, you discover that you have the ability to import ideas across languages. And it’s really amazing.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So for now, for example, I’m writing this memoir and I’m taking all the lessons I’ve learned from writing op-eds into this memoir, because I’ll give a little… With that op-ed for the New York Times on creative risks, I gave my editor a 2,500 word op-ed, and the one that you see published is 1200 words. Okay. So op-ed editors are not precious about you’re writing this, cut, cut, cut. And that’s been really amazing for writing this memoir, for example, the chapters that are about 2,400 words in the first draft, and I’ve literally chopped out six or 700 words per chapter in the revision process so far, and hopefully more will go. So it’s hard to learn the different languages of your different writings, professions, but in the end, if you do, they will feed into each other.

Matt Weinkam: Erin had another great question in the chat that ties in with our theme, which is, are there risks not worth taking? Are there things that count as too far out? Are there things that here’s places where you draw lines? Yeah. And as both risky writers, I’m curious to hear where your boundaries lie.

Thrity Umrigar: Well, at this point in my life, I probably would not write a novel set in Singapore with characters whose culture speak speech patterns, etc, I know very little about. So all of us who teach writing, at some point, even if we have not actively said this, we’ve encountered the old chestnut of write what you know. And that to me has always been this double edged sword, because it seems to assume that, that knowledge is finite and the whole point of knowledge, the whole beauty of knowledge is that it’s not, it’s infinite. So what you know today is not going to be the same as what you know two years from now. So write what you know but know more than you know. That’s what I would attach to that.

Thrity Umrigar: I’ve written a novel that had no Indian characters that set entirely in the US. And the main characters are a white patrician man, the heir of a US Senator, political family, blue bloods, and his adopted African American son. I’m not a member of either group. And I didn’t write that novel until I felt confident that I wouldn’t make a fool of myself telling that story. And thankfully, I don’t think I have. But I had to really, really learn those cultures well enough to be able to put that foot forward and write that novel. So yeah, there are many risks that I wouldn’t take just because I’m not equipped to tell other people’s stories. But that also does not for me, suggests that I cannot work on increasing that sphere of what I do know, but I have to be able to feel somebody else’s story in my bones before I feel I have any right to telling it.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Just add onto that, I think you have to want to take a risk. So the Singapore example, if you don’t want to take the Singapore risk, why do it? But also with risks, I think you prepare yourself to take a risk. You’d be stupid if you have zero training in gymnastics and then you want to do the Simone Biles move. You’re going to break your neck doing it. But Simone Biles has spent thousands of thousands of hours getting herself ready to do these incredible moves. And so she is prepared to take a risk. And I think we have to prepare ourselves to take a risk.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Now, that being said, I’ll give you my own real life example. When The Committed came out, I wrote an essay to accompany a nonfiction essay. I won’t tell you what the topic is, but I gave it to my editor, my publisher, my agent, and they said, “It’s a great essay, but are you sure you want to publish it, because it could have negative ramifications for your professorial life?” And I thought, “I think you’re correct.” So that essay is in my pocket, it’s waiting to be published once I decide to terminate my professorial life, which hopefully happens sooner rather than later.

Matt Weinkam: You have the grenade, you’re just waiting. I want to end with one. I’m sorry, everyone had really great questions. I apologize, we didn’t have time to get to all them all. But I want to ask one more question. This is a writing conference and I know there’s a lot of writers out there, I’m curious what risks you would encourage them to take? What do you want to see emerging writers of any age be willing to tackle and take on?

Thrity Umrigar: One word, honesty. I would tell them to take the risk of being honest, to tell the truest story that they know, not the most factual, because that’s journalism. But in terms of art to tell a story as best as they understand the truth. I can’t stress that enough. And that’s speaking of taking risks, it’s funny in this whole conversation we’ve been talking about risks in terms of audience reception, in terms of what the publishing industry has to say, but sometimes the scariest people are the people in your life. You can say things that can really, really hurt somebody that you love, somebody that you care about. And yes, if it’s fiction, there’s this additional layer of fat that protects you. You can hide behind that and say, “Well, this is not the truth.” But people are not stupid, people recognize themselves in not just anecdotes, but in characters too. If you believe that your story is worth telling, I think you have to take that risk.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: So honesty and truth, those key words are very important. I totally agree. The example I’ll offer is from something that one of my writing teachers told me, which I had a very hard time understanding. That was Bharati Mukherjee, who was teaching at Berkeley, and I took her a class. I was a B+ student, wasn’t very good writer of fiction. So afterwards, she said to me, “You have to cut to the bone in your stories.” And I was like, “How do I do that? That’s a great metaphor, how do I do that?” And so that is something that you don’t learn in writing workshops. In writing workshops, you can learn about point of view and narrative time and all that kind of thing, but no one can teach you how to cut to the bone, which is related to honesty and truth.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And for me, the way I eventually understood it is that I had to go where it hurts. So as a fiction writer, you make up all kinds of things, all kinds of characters and plots that are not autobiographical, but what is the autobiographical element you can inject in there is your emotion. You feel things. And where do you find the feeling? The feeling is in your own life. And so the advice that she was giving me and also Maxine Hong Kingston, who was also my teacher at that time, is related to this autobiographical stuff that I was writing when I was an undergraduate, but I could not get close enough to the material, because it was too terrifying for me.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And the memoir I’m writing now is about that, what I was writing about then. And in other words, it took me 30 years to get to the point where I could finally go back to this terrifying, painful experience where I could not cut to the bone, but now I hope I can do it. So I know that might be daunting to think it could take decades to come closer to where the pain is and where the hurt is, but hopefully it’s inspiring in the sense that you can do it.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: And part of the discipline for me of being a writer is to prepare myself to cut ever deeper and ever closer and try to get closer to the thing that most sensible people would run away from. Most people don’t want to go to where it hurts, they want to move away from there. But I think part of the courageousness or the full heartiness of being a writer is to go where your emotional instinct tells you not to go, because it’s going to be so painful.

Thrity Umrigar: This is so true. For years when people would say such and such character autobiographical, and I would just say no, because as a younger writer, I wanted to prove that my imagination was at work rather than memory. I’m talking about in fiction. Somehow that felt… And now I think I would just say yes to any such question about any character, because the fact is you can have a character who is violent, who kills people, who does the worst possible stuff, but how do you create that character? You are by definition, I think drawing on some part of yourself, some part of your psyche, some part of your soul, something within you that allows you to imagine that kind of behavior. So I think in some sense, all characters are based on your life, they’re based on your inner life or at least your inner thoughts. So I think that’s right on the money bit.

Matt Weinkam: Cut to the bone, everyone. Join me in thanking both of our presenters for tonight. Viet and Thrity, this was so wonderful. Thank you so much for your time. And those of you out there, we can’t see your standing ovation, so please put it in the chat for us. We so appreciate your conversation, your time tonight. Everyone, go out and get these books if you haven’t, especially from our friends at Loganberry Books, check out The Committed, The Secrets Between Us. Pre order Thrity’s new novel, Honor. We’re so excited to be able to partner with Loganberry Books, which is one of our favorite stores here in town.

Matt Weinkam: Before you go, just a couple notes here. The conference is not quite over. Sunday is our last day. Tomorrow morning there’s a panel on solutions journalism with some of the best local journalists in Cleveland. Tomorrow evening, our keynote with Claudia Rankine, you do not want to miss that. So return back. On Sunday, a very fun panel on storytelling to affect social change from writers who are really using storytelling in a real activist sense. And then our closing ceremony on Sunday. All events are free. So please join us for those wherever in the country or the world you’re joining from. There’s still a little bit of time to become a member of Literary Cleveland. We’d love to have you be part of our community. And check out our fall class list too.

Matt Weinkam: Viet, Thrity, this was so wonderful. Thank you so much for your time. We really appreciate it.

Thrity Umrigar: Thank you, Matt. [crosstalk 01:07:51]. And thanks, Lisa. Thank you for inviting us.

Viet Thanh Nguyen: Bye.

Lisa Chiu: Bye, thank you.

Thrity Umrigar: Bye.

Matt Weinkam: Bye everyone. Have a great night. Thank you.