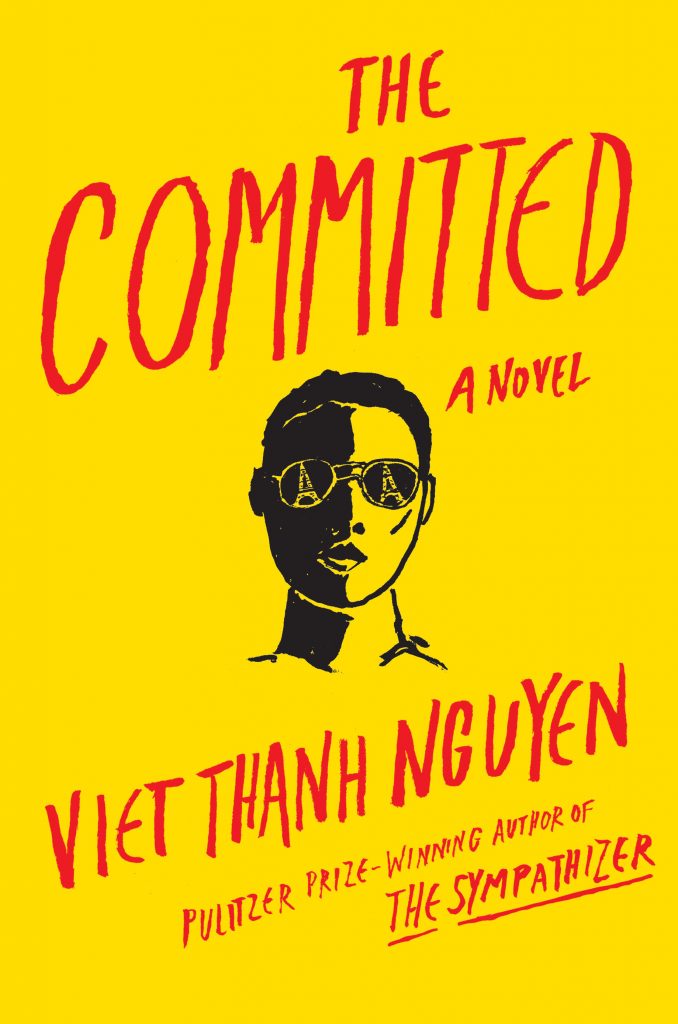

Ron Charles reviews The Committed for the Washington Post.

In 2015, a professor at the University of Southern California published his first novel called “The Sympathizer.” The story was a cerebral work of historical fiction and political satire cleverly infiltrated with cultural criticism. Although cloaked as a thriller, it didn’t fit neatly into that popular genre and could have slipped by as unnoticed as a good spy.

Except that the author, Viet Thanh Nguyen, was too startlingly brilliant to ignore. “The Sympathizer” flushed color back into those iconic photos of the fall of Saigon and recast the worn lessons of the Vietnam War through the eyes of a communist agent hiding in the United States. An instant classic, the novel aggressively engaged with the nation’s mythology and demonstrated Nguyen’s extraordinary intellectual dramatic range. “The Sympathizer” swept through the year’s literary awards, winning a Pulitzer Prize, a Carnegie Medal, the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, the Asian/Pacific American Award, an Edgar Award and more.

Now, Nguyen returns to the scene of that triumph with an even brainier sequel called “The Committed.” “I may no longer be a spy or a sleeper, but I am most definitely a spook,” the unnamed narrator begins. “I am also still a man of two faces and two minds, one of which might perhaps yet still be intact.”AD

If you read “The Sympathizer,” you’ll immediately recognize this ironic and endlessly conflicted voice. If you haven’t read “The Sympathizer,” you’ll be hopelessly lost, so don’t even think of jumping in here. The setting and action of this second book are different, but “The Committed” is so dependent on earlier relationships and plot details that these two novels are more like volumes of the same continuing story.

“The Committed” never sets foot in the United States. Instead, it takes place entirely in Paris, though not the romantic City of Light. This is Paris beyond the tourist haunts and photo shoots: along dark avenues of warehouses, clubs and restaurants controlled by battling gangs. Just as “The Sympathizer” transformed the hulk of an old spy novel, “The Committed” does the same with a tale of noir crime.

The novel opens in 1981 when the dangerously sympathetic spy arrives in Paris with his old friend Bon. They have survived a year of torture in a reeducation camp in Vietnam and are now being rewarded with new lives among the French. “Our bags were packed with dreams and fantasies,” the narrator says, “trauma and pain, sorrow and loss, and, of course, ghosts. Since ghosts were weightless, we could carry an infinite number of them.”

Those ghosts — which include his French father, a priest — interact with the living in this new Parisian arrangement. Although the narrator is no longer a professional spy, his life is no less clandestine than ever. Bon, his blood brother, is still determined to kill communists and has no idea that the narrator is one. But perhaps that won’t matter in their new line of work as underlings for a Vietnamese drug lord. Here, surely, they can just pretend to be waiters at “the worst Asian restaurant in Paris” and brush ideological concerns aside while collecting protection money and distributing hashish.

Au contraire. In France, the narrator finds himself contending with attitudes far murkier than anything he experienced in the proudly fantastical United States. Here, his hosts are seductive patrons and brutal colonizers, as pleased with their aesthetic superiority as they are with their racial dominance. That creates a profoundly unsettling environment for immigrants. “Loving a master who kicks you is not a problem if that is all one feels,” the narrator explains, “but loving and hating must be kept a dirty little secret, for loving the master one hates inevitably induces confusion and self-hatred.” And that painful conundrum is invested in their most prized possession, the French language, which immediately announces the refugee as the other, the intruder, the barbarian. “There was no need for the French to condemn us,” the narrator says. “So long as we spoke in their language, we condemned ourselves.”

Beneath the facade of Parisian elegance, Nguyen describes the carnage of ethnic violence carried out by Vietnamese and Algerian immigrants competing for territory in the narcotic trade. With alarming regularity, drug deals go bad and crooks seek vengeance in the language they all speak fluently: pain. As in “The Sympathizer,” “The Committed” is dedicated to the proposition that with patience and the right tools a person can be liquefied with exquisite care.

But all that agony — and there’s a lot of it — is subsumed within the narrator’s introspection. “My life as a revolutionary and a spy had been designed to answer one question,” he tells us, “WHAT IS TO BE DONE?” As a man riddled with sympathy, riven with a nagging appreciation for all sides, he’s doomed to bewilderment, to irony, to a maddening sense of his own irreconcilable doubleness. “All my life I only ever aspired to one thing — to be human,” he cries. But to what cause should he be committed? Or should he, instead, be committed to an asylum? Perhaps only the nothingness of Sartre can offer him relief.

“The French and the Vietnamese shared a love for melancholy and philosophy,” the narrator says, “that the manically optimistic Americans could never understand.” The same hurdle will challenge American readers of “The Committed,” which is heavily fortified with philosophical rumination. In this novel, even the whorehouse bouncer reads Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire. If the man’s size doesn’t scare you away from the pleasures within, his bookshelf might.