Vince Schleitwiler reviews The Committed for the International Examiner.

When your debut conquers the world, how do you top it?

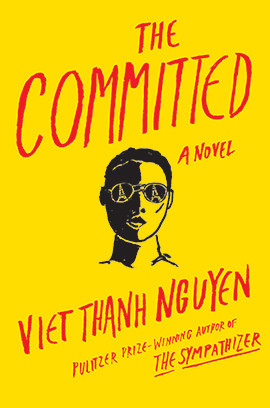

Few writers have experienced the overwhelming acclaim that greeted Viet Thanh Nguyen’s first novel, The Sympathizer, which made him the go-to Asian American voice for elite cultural institutions. He’s leaned into that dubious role with admirable self-awareness and political edge, but the twin burdens of success and racial representation have brought down many talented artists.

Nguyen knows this. He modeled The Sympathizer on Invisible Man, and named his son after its author, Ralph Ellison, whose struggle to complete a second novel is legend. Yet six years later, after publishing a critical study on the cultural afterlife of war, a quietly impressive short-story collection, and a children’s book cowritten with his son, Nguyen has chosen to tempt fate, and the haters, with a sequel.

Everyone asks for a sequel, but no one loves it. When there’s an exception, that rare “better-than-the-original,” everyone secretly resents those, too. So Nguyen tripled down, making his new book, The Committed, part of a trilogy.

Let’s get this out of the way: Is it good? Yes, it’s good! Sure, it can’t compete with the splash of his first book. And with a third coming, it’s not supposed to outshine the others. But ranking favorites is an exercise for those too stingy with their love. Today is for the middle child, in his glory.

If you haven’t read The Sympathizer, don’t worry. The Committed carefully recaps its plot points: the pact of brotherhood that the nameless Vietnamese narrator swears with his friends, Bon and Man, who would take opposite sides in their country’s war; his experiences as a double agent, serving and spying on an anticommunist general in U.S. exile; the series of cruelties and betrayals that reunite the friends, then leave the narrator and Bon to become refugees a second time over. All these details are deftly recalled in the dazzlingly clever voice that distinguished the first book – one you can’t forget, even if you want to.

Oh, and he brings up the thing with the squid again. You thought he wouldn’t?

A narrator this good can take a novel anywhere. The Committed follows him to Paris, a refugee sponsored by a pretend “aunt.” His contact from his days as a Communist spy, she knows the secret he cannot reveal to the fanatically anticommunist Bon, with whom he is acclimating to French society as employees of a violent criminal operation.

Shifting from spy thriller to gangster flick, and from Southern California to Paris, makes sense for a sequel, but these choices are justified by the history of the Vietnamese diaspora. The crime story is less satisfying – more post-Tarantino indie-film pastiche than the gangster we are still all looking for – but the change in setting is the key to the book. Who can appreciate the combination of love and hate French culture bequeathed on its former colonials than ex-PhD students from the 1990s heyday of French literary theory? Nguyen falls into both categories, so inevitably his narrator ends up dealing drugs to Parisian intellectuals.

This setup allows Nguyen to grapple with classic anti-colonial thinkers, like Fanon and Césaire, while squaring accounts with French philosophy. Add to that the narrator’s compulsion for literary references, and scholars will feast on the book for years. But don’t let the displays of erudition intimidate you, because its most profound questions, about forgiveness and power and commitment, are ones that every reader already knows intimately. And Nguyen is the kind of writer who makes sure you have everything you need.

The allusions are a bonus, often meant for the sheer joy of recognition, like when a character breaks out a tin of Danish butter cookies. You don’t have to be a child of Vietnamese refugees to be in on the joke, because the mystical connection between tins of Danish butter cookies and your ethnic or class identity is pretty much universal, except maybe for the Danes.

Can it become a bit much? Sure. Nguyen famously diagnosed Asian American cultural representation as suffering from “narrative scarcity” rather than “narrative plenitude,” a problem his narrator sometimes seems to try to solve singlehandedly. What worked so well in The Sympathizer still works in The Committed because of their picaresque spirit – they feel like endlessly extendable collections of set pieces – but there are limits.

By placing him in a satire of the priapic arrogance of 1980s French intellectuals, for example, The Committed exposes the narrator’s own vacuous sexism, which can’t be laughed off. Nguyen recognizes this, but a proper reckoning for his character is not really possible within the story. Instead, he forces him to read French feminist theory, with predictably disappointing results.

Worse, this leads you to realize that back with Ellison in the novel’s family tree are a stack of those tediously clever white-boy novels you stopped reading after finishing your English major, and never missed. And Invisible Man is closer to them than you’d like to admit. Nguyen’s narrator could use less Kristeva, and more Black feminism – I wish he could hitch a ride with the truckdriver-narrator of Gayl Jones’s equally brilliant and erudite novel, Mosquito.

Nonetheless, like its predecessor, The Committed arrives at a conclusion that’s narratively original, intellectually satisfying, and emotionally powerful. The brilliance of the narrator’s voice wears on him, too – it’s the sound of a man trying to outrun his own death, in language.

Twice in the book, he turns around to face it. But the tragedy is that he survived his death long ago.

This is why, in a running gag, the narrator’s competence as a gangster is undercut by his tendency to break into fits of inexplicable crying. And this is why the most impressive quality of his voice is not wit, but an ability to effortlessly hurtle decades in the space of a paragraph, immersing you in the vivid presence of each memory so deeply that it never occurs to you to ask how you got there, or why.

Trauma is too small of a word for the experience to which this story lends form, and two fat volumes aren’t enough to carry all the grief that a refugee is denied. I don’t think three will hold it, either. Nguyen says his working title for the last book – unless it’s a clever joke! – is The Unfinished.