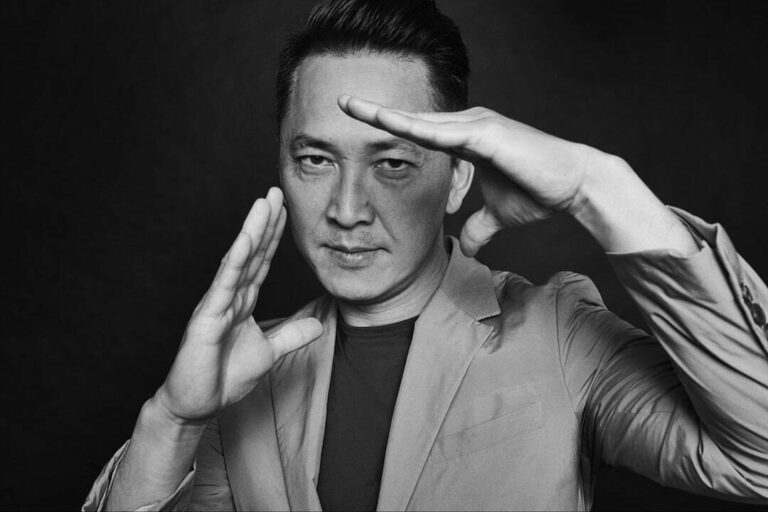

In this profile by Alexandra Alter for the New York Times, Viet Thanh Nguyen reflects on memory and what that means for his narrator in The Committed.

In one of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s earliest memories, he is on a boat leaving Saigon.

It was 1975, and he and his family had been turned away from the airport and the American embassy but eventually got on a barge, then a ship. He can’t remember anything about the escape, other than soldiers on their ship firing at refugees who were approaching in a smaller boat.

It is Nguyen’s only childhood memory from Vietnam, and he isn’t sure if it really happened or if it came from something he read in a history book. To him, whether he personally witnessed the shooting doesn’t matter.

“I have a memory that I can’t rely on, but all the historical information points to the fact that all this stuff happened, if not to us, then to other people,” he said in a video interview earlier this month.

Real or imagined, the image and feeling stayed with him and shaped his new novel, “The Committed,” a sequel to his Pulitzer Prize-winning debut, “The Sympathizer.”

Like “The Sympathizer,” “The Committed,” which Grove Press will publish on March 2, hinges on questions about individual and collective identity and memory, how wars are memorialized, whose war stories get told and what happens when abstract political ideologies are clumsily deployed in the real world. It is packed with gunfights, kidnappings, sex and drugs but delivered in dense prose that refers to obscure scholarly texts and name-checks philosophers like Sartre, Voltaire, de Beauvoir, Fanon and Rousseau.

“The Committed” opens with a scene that feels Homeric, as a group of refugees make a treacherous journey in the belly of a fishing boat. As a refugee — and as someone who often points out that he is a refugee, not an immigrant — Nguyen wanted to use epic imagery to describe the voyage, to counter the stereotype of refugees as pitiful and weak.

“From the perspective of the West and people who are not refugees, boat people — people who flee by the sea — are pathetic. They’re desperate, they’re frightened, and they’re just objects of pity. I wanted to refute that,” he said. “You’ve got to think of them as heroic.”

In “The Sympathizer,” an unnamed Communist spy goes undercover as a refugee in Southern California after the fall of Saigon. When a reconnaissance mission goes awry, he finds himself in a Communist re-education camp, where he is tortured by his best friend and former handler.

In “The Committed,” the narrator — who calls himself Vo Danh, or “Nameless” — has escaped his Communist interrogators. He heads to Paris and joins a gang of drug dealers, the ultimate act of capitalist rebellion. He’s no longer sure who he is or what he believes in. His identity, mission and even his consciousness — he sometimes refers to himself in the second person — have been fractured by displacement, disillusionment and torture.

To the French natives he meets, he is among “les boat-people,” a label he rejects. “I was not a boat person unless the English Pilgrims who fled religious persecution to come to America on the Mayflower were also boat people,” the narrator thinks.

Nguyen, who is 49 and teaches at the University of Southern California, now lives in Pasadena with his wife, Lan Duong, and their two children, Ellison, 7, and Simone, 1. Though he’s lived in California for most of his life — he was 4 when his family left Vietnam — he is still unsettled by the feeling that he would have become a very different person if his family hadn’t escaped.

“That idea of an alternative life, parallel life, alternate universes, has always haunted me,” he said. “It haunts a lot of us who are refugees from Vietnam, what our lives could’ve been, and so I think that sense saturates my fiction and my nonfiction.”

After they fled Vietnam, Nguyen and his family ended up in a refugee camp in Pennsylvania. Nguyen was separated from his parents and brother for several months and placed with an American family. He remembers screaming when his host family took him to visit his parents, then took him away again.

A few years later, his family moved to San Jose, Calif., where his parents opened a Vietnamese grocery store. One Christmas Eve, when Nguyen and his brother were home watching “Scooby-Doo,” his parents were shot during a robbery. When he was 16, an armed intruder tried to rob their home.

Nguyen began writing fiction in high school (he got an early taste of literary fame in the third grade, when he wrote a book called “Lester the Cat” that received a prize from the San Jose Public Library). At the University of California, Berkeley, where he got degrees in English and ethnic studies, he devoured literature by Asian-American and Black writers, developing a particular affinity for Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man.”

He studied writing with the novelist Maxine Hong Kingston and recalls being a “terrible student.” (Kingston disputes this: “Viet says that he slept through my classes. I always saw him with his eyes open,” she wrote in an email.) Throughout college and graduate school, he wrote short stories that featured Vietnamese refugees and victims of the war. The summer after he finished his doctorate in English, he had enough for a collection.

“I thought, here it is, I have the basis for a book,” he said. “I did not realize it would literally take 20 years before that book would be published.”

Nguyen found an agent, Nat Sobel, who told him a novel would be an easier sell than a story collection. Over the next few years, Nguyen wrote “The Sympathizer,” using the form of an espionage novel to slyly deconstruct the ways the Vietnam War has been depicted in film and fiction.

“I wrote it optimistically, thinking there should be hopefully an audience for something like this, and if not, then I’ll create the audience,” he said. “I deliberately chose a dense, imagistic style to provoke resistance on the part of readers. I didn’t want the readers to have a transparent relationship to the story.”

At first, it seemed like he had been overly optimistic. Thirteen publishers rejected it before Peter Blackstock, an editor at Grove Atlantic, made an offer. Blackstock said he was captivated by the “clarity of voice and the metaphorical, rich prose,” and by Nguyen’s provocative subversion of the spy thriller.

The book received ecstatic reviews when it was released in 2015, and sales were decent for a literary debut, at around 30,000 copies. Then Nguyen won the Pulitzer Prize and later, the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Award for best first novel, a rare instance of a novelist winning mainstream and genre-specific prizes for a single work. “The Sympathizer” went on to sell more than 1 million copies worldwide, and Nguyen was suddenly in demand as a speaker, panelist, late-night TV guest and op-ed writer, speaking up for refugees and immigrants at a time when both groups were being demonized.

The accolades and attention were great for his career and terrible for his work. For the next year, he barely wrote a word of fiction. “After the Pulitzer Prize I turned into a — please put this in quotes — ‘public intellectual,’” he said. “Maybe I just handled it badly.”

Luckily, he had two decades of unpublished writing to draw from. He quickly followed “The Sympathizer” with his story collection, “The Refugees,” and a work of nonfiction, “Nothing Ever Dies.”

Initially, Nguyen didn’t set out to write a series about a disillusioned spy. But when he finished “The Sympathizer,” he had grown attached to his sardonic narrator, whose voice came to him so naturally that it feels like his alter ego.

“I cannot say as an academic the things that I say in ‘The Sympathizer,’ so writing it really freed me,” he said. “I could take all these ideas and arguments I already had and put them into the mouth of this guy who could express it in the most, you know, obnoxious way possible.”

Nguyen is now planning the third and final book in the series, which will follow his narrator as he returns to the United States to “tie up loose ends.” He’s also working on a memoir, titled “Seek, Memory,” in a nod to Vladimir Nabokov, that exhumes memories he has repressed for most of his adult life.

As he excavates his past, Nguyen has had to confront the fallibility of his recollections.

“The book is partly about memory, but of course the issue about memory is, my memory is not reliable, I think things happened that didn’t happen, and vice versa,” he said.

In his fiction, Nguyen has described the porous nature of memory in evocative ways, comparing it to stains left behind by lime deposits, a laminated floor that can be hosed off, the bone marrow that flavors broth. When the narrator of “The Sympathizer” laments that he can’t recreate the dishes he craves from home, it reminds him of everything he’s lost and forgotten. What he’s left with is a disappointing aftertaste: “the sweet-and-sour taste of unreliable memories, just correct enough to evoke the past, just wrong enough to remind us that the past was forever gone.”