Adraian Lentz-Smith interviews Viet Thanh Nguyen about his thoughts on the line between fiction and nonfiction and how that may affect the sense of what is real for Visitors’ Corner.

Writer and scholar Viet Thanh Nguyen advocates in his work and teaching for a project of intellectual, aesthetic, and political decolonization to address pernicious and pervasive inequities. Representation is not enough, he argues: we need a reckoning. Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, The Sympathizer (Grove/Atlantic, 2015), calls—at times almost literally—for an interrogation of the past. In it, and in his collection of nonfiction essays, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War (Harvard, 2016), he explores how individuals, communities, and nations traffic in histories of colonial violence and racialized and sexualized power, as well as how they process loss to give structure and meaning to life in the present. In July 2020, Adriane Lentz-Smith interviewed the celebrated author, who shared his thoughts about the relationship between fiction and nonfiction, the past and the present, and the ways in which narratives shape our sense of what was, what is, and what might be.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is a MacArthur Fellow, a Guggenheim Fellow, and University Professor, Aerol Arnold Chair of English, and professor of American studies and ethnicity, and comparative literature at the University of Southern California, where he has won numerous awards for teaching and mentoring. Born in Ban Me Thuot (now Buon Me Thuot), Viet Nam, he describes himself as a refugee, first-generation college student, and beneficiary of affirmative action. In addition to writing and editing books and short stories, he also serves as a contributing writer for the New York Times, and has published in numerous other outlets including the Guardian, the Atlantic, and Ploughshares. His upcoming sequel to The Sympathizer is entitled The Committed.

You were an academic before you were a fiction writer. Why write a novel?

My childhood ambition was to be a writer. I don’t know many people who want to grow up to be professors unless their parents were academics. In my case, I wanted to be a writer, and I then became an academic because I thought it was safe. But that was my day job, basically, and I took steps necessary to get and keep that day job. Once I got tenure, I thought to myself, “I’m going to do exactly what I want to do, which is write fiction.” I wrote short stories. Then my agent told me I had to write a novel, so that’s technically why I wrote a novel. But really, the ambition behind writing a novel is to tell a great story, but also to say something grand.

That’s the kind of novelist I’d like to imagine myself being: one who says something grand, whether it’s about the human condition or politics or history or hopefully a combination of all those things. In the case of The Sympathizer, I think that there was a certain amount of risk involved because I was still an academic and academics sometimes have a hard time understanding the nonconventional. Everybody, as far as I could tell, was patting me on the head and treating my writing as a kind of a hobby—even after the novel was published. Only after the novel won prizes did people begin to concede that this was something legitimate, which is unfortunate. Really, I believe in both enterprises, fiction and academic work. And I just wish that people on both sides would understand the validity of what everybody else does.

I admire certain kinds of historians. The ones I like to read can tell a story. That is not true for all historians, but it’s almost certainly not true for most literary critics. Many historians are crafting narratives, and I actually find that very inspirational. For example, I read This Republic of Suffering by Drew Faust before I wrote my second academic book, Nothing Ever Dies. The book inspired me to think of how one can tell a story in academic nonfiction, and that was a crucial decision for me at the time.

I love a novel full of ideas that understands how to work on the border, so within and outside of genre. That’s one of things that I appreciate about The Sympathizer.

I think that’s crucial. We’ve been talking implicitly about categories, fiction, nonfiction, academia, creative writing or whatever you want to call it. But the stuff that interests me is the stuff that exists by crossing borders, by drawing from different things. The Sympathizer, as you said, is a novel of ideas. It’s also, in my mind, like an academic novel, because I was trying to draw on various kinds of academic thinking and theories that have been important to me.

Likewise with the nonfiction or the academic writing that I do now. I can no longer be called a pure scholar; I think I’ve given that up. The writing that I do now in the nonfiction or scholarly vein is often inflected by personal narrative, memoir, and various kinds of narrative devices, because I just think it makes things more interesting to read. At this point, I really like to read academics who like to take chances with their writing and draw from different discourses.

Why write historical fiction (say, instead of contemporary fiction)?

I never was interested in writing an historical novel; I was interested in writing a war novel. That required me, in the case of the war that I was interested in, to go into the past and to write a history.

The reason why I wanted to write a war novel is because, as someone who is a refugee from Vietnam and the war there, I understood that my place in American letters was to tell the story of Vietnamese refugees. That’s the logic of race, commodification, multiculturalism that saturates the publishing industry—that creates opportunities and also enclosures for writers of color. While I was not interested in only doing that, I was interested in doing it. I wanted to write about refugees, but the larger ambition was to make this claim that you can’t separate refugee or civilian experiences from war experiences.

This would be a direct attack on the way that Americans understand the Vietnam War specifically, but all kinds of wars in which Americans are involved. It would be an attack on this whole system that that places someone like me into a certain kind of a category and says, “Well, you can talk about this experience as a refugee here in the United States and the American dream and all that. But it’s Americans and American soldiers and American men, white men specifically, who get to talk about this war.” So there was a huge narrative desire to break all these things down, but also that’s born from a political and theoretical impulse of critique based on our understanding of what a war is, what race is. So that was really the driving ambition to take me back into history. I’m not sure I would want to do that again, except the sequel that I just wrote is still a historical novel because it picks up from where The Sympathizer left off and doesn’t get out of the 1980s.

Do you find a particular defensiveness around the Vietnam War on the part of white Americans? Do people respond to, say, World War II or Korea differently?

When we talk about wars in which most of the people are already dead, there’s probably a greater liberatory possibility. All of this writing takes an act of imagination: just because you’re a soldier now doesn’t mean you’re qualified necessarily to talk about World War II any more than a civilian is. So with the Vietnam War, I think that the fact that there are people who are still alive, who went through that experience, who could use their claims of authenticity to having fought there, has something to do with this sense of ownership.

The fact that most of the soldiers who get to tell their stories are white men has something to do with this, too: you can’t take away whiteness and masculinity from this claim of authentic ownership of this war experience. Also, I think the fact that a lot of Americans have deeply ambivalent feelings about this war further compounds this. You know, they feel guilty, or they’re angry that they might feel guilty.

And then someone like me comes along. To generalize, the place for someone like me is to tell about my experiences; but if I talk about the experiences of the war that seemingly belong to white male soldiers or just white men, then I’m infringing on a territory that I’m not expected to be on. That can produce defensiveness. I certainly get my share of hate mail and critique either about this novel or about, you know, essays I publish in the New York Times or Time magazine, where I get into the whole territory of American identity and nationalism and war and so on. And if I were to talk about these things and say, “Thank you, America, for rescuing me,” then that’s perfectly acceptable. Again, that is our [refugees’] place. But if I were to say, “You know, I wouldn’t be here unless Americans had been there and invaded this country,” people just freak out. And basically, that’s what The Sympathizer says.

So all these things are wrapped up together. Questions of identity, of who gets to write about certain things and what the United States is and what is a Vietnamese person or what is a minority supposed to say or do in this country.

How did you go about researching for your fictional work?

I grew up obsessed with the war because at a certain point in my youth, I realized that was what had brought me here to the United States, so by the time it came to writing the novel, I had already done 20 years of research as a hobby. I knew a lot of things about the war in general, conceptual things, historical things, anecdotes about the Vietnamese experience that Vietnamese refugees knew very well, but most Americans didn’t know anything about. In terms of writing a novel, all that is very useful, but much of it remains background material. It provided me some useful information, like certain real historical figures to model my characters on and certain real historical incidents. Many people who read The Sympathizer may be surprised by the things that happened in there, but 98 percent of what happens in the novel is drawn from real incidents or real personages.

Still, I did have to do some very specific historical research as a novelist in order to create fiction. So, for example, the first fifty pages of the novel is the Fall of Saigon. And I knew what that was about, I knew the rough outlines, but in order to create a fifty-page narrative description, I had to go and read everything that was available about the fall of Saigon, because what I needed to know as a novelist was what happened on this day. What happened on the street that refugees had to use to get out of the city? What time were rockets falling on the airstrip? What torture techniques did the secret police use? I gleaned these details from research. Those were the kinds of nuts and bolts things that the writers have to do that theoretical scholars don’t necessarily have to do.

What kinds of decisions do you make about using historical scholarship, versus oral histories or community memories, etc.?

The decision I made was that I wasn’t going to go out of my way to track down people who lived through this experience. Some writers go out and interview a lot of people to get the information they need, and sometimes they do that because there isn’t an archival record or there aren’t historical books written about these experiences. I’m thinking of Min Jin Lee’s Pachinko, where she interviewed a whole bunch of people about the Korean experience of migrating to Japan.

In my case with The Sympathizer, there was a ton of work, scholarly historical work and oral history compilations and so on and so forth. So I didn’t really feel the need or the urgency to go out there and find my own witnesses to this particular history. Growing up in a Vietnamese refugee community, I felt that I was already immersed in their experiences of the 1980s, the sentiments, the experiences, the world views. I didn’t need to interview more people than what I already had grown up with. For the sequel to The Sympathizer, which is set in Paris of the 1980s, I felt a little bit more of an obligation to ask questions of people, because the novel is set in the Vietnamese community in France, in Paris, and there’s not a whole lot written about them.

Plus, I had very particular questions that French people probably would not ask French people of Vietnamese descent. I was coming at this as an American with a different sense of racial politics than French people have. In the novel, I explicitly wanted to do a comparison of racial understandings between France, the United States, and Vietnam, because the novel is a critique of colonialism and imperialism, how these regimes operate differently whether you happen to be French or American, and the place of colonized or formerly colonized peoples in France or the United States. So I had a whole bunch of conversations asking what could have been, and for French people of Vietnamese descent, these were potentially unsettling questions because they had never thought about these issues from the perspective of an American with my particular hangups about race. Those conversations were crucial.

Does it matter if novelists get all the historical details just right?

There’s no right answer to this question. Some readers want to be immersed in a nineteenth-century-style realist novel where everything is described. You want to make sure that you have the right place setting in a house, and you don’t want to get that detail wrong because someone who knows that that’s not what was used will be upset.

And then there are other sorts of novels. For example, a lot of French novels that I read are skimpy on details. The ambition is not to create pointillist recreations of a certain place and time, but to create moods and feelings. The last book I read in that style was David Diop’s new novel called Soul Brothers in French and in English, All Blood Is Black at Night. It is about Senegalese soldiers fighting for the French in World War I. It’s not some kind of rich, immersive history of the war or the Senegalese experience; it’s much more of a philosophical novel about the soul struggles of two particular Senegalese soldiers. It’s very internalized. And that, to me, works perfectly fine.

What other writers inspired you when writing The Sympathizer? Did you have any anti-models?

As for anti-models, in general, I think a lot of American fiction about war, as I said, takes up the experiences of white male soldiers, and I did not want to do that. At the same time, a great deal of Asian-American fiction—or Vietnamese American fiction, which I would be categorized under—restricts itself to the immigrant experience or the American dream and is not strong on anti-imperialist and anti-colonialist critique. It shies away from class critique and Marxist consciousness (there is a strain of that in Asian-American literature, but the kind of Asian-American literature that gets privileged, prioritized, marketed, sold today is not that kind of stuff). I did not want to go in either of these directions.

The book was influenced by writers I admired, who I felt were very critical and very caustic. I wanted to write a novel that was going to be fun to read, and so would have a character who is not only some kind of a Marxist critic, but also who would be libidinous. It was important to me that this novel be fun, that it wouldn’t fulfill some American stereotype of political literature that has to be dry and didactic. I wanted a novel that could be didactic because I think the novel is didactic—I wanted to reclaim didacticism—but that would also be immersed in in the pleasures of the narrator.

Some of the writers who I felt had accomplished this well included Louis-Ferdinand Céline in Journey to the End of the Night and António Lobo Antunes’s The Land at the End of the World, which is an autobiographical novel about a young Portuguese man who is drafted as a medic to fight a colonial war in Angola. It’s a very bitter, very funny novel, and rich in language. I wanted The Sympathizer to be rich in language as well, for better and for worse, because I was reacting against this idea that Asian-American writers have to prove our English ability. My attitude was, “Okay, I have to prove my English ability by just going to excess.”

Finally, maybe the last major one that I can think of off the top of my head would be W. G. Sebald—his whole corpus of work including Austerlitz, Rings of Saturn, and On the Natural History of Destruction. Here’s a guy who had no sense of humor, but he was a beautiful writer with thick, dense language, whose novels cross the line between fiction and nonfiction and dealt with history and memory and war. These were all concerns that I had as well.

What can writers do with novels or short stories that they cannot do with nonfiction? What can writers accomplish in nonfiction works that can’t be done in fiction?

I’m interested in writers who try to cross over. So Sebald, for example. When I read his fiction or nonfiction, I can’t distinguish the voice between the two. Whether it’s Austerlitz, a novel about an orphan trying to recover his Jewish past after World War II, or On the Natural History of Destruction, a work of scholarship and criticism about the allied bombing of Germany during World War II, the voice is almost exactly the same—the rhythm of the prose.

I really admire that accomplishment because his project is important. He is interested in the power of narrative, not the power of genre—not “I have to be a fiction writer or novelist” or “I have to be a historian.” His work is about the power of narrative to allow us to approach the past, whether from the angle of fiction or nonfiction. That has always been my ambition.

But generally speaking, fiction and nonfiction take different directions. With fiction, you’re allowed to break rules. For example, I think of The Sympathizer as a work of scholarship without footnotes because I could say all kinds of outrageous things in that book which I think are true but which I would have to do all kinds of research to prove in a university press book. Fiction can be just as truthful as scholarship, but it’s free to forego the apparatus of footnotes and the like. It just lays out its argument, and readers have to grapple with it, accept it, reject it, whatever. Yet because it has that possibility of freedom from the proof required in nonfiction, it may be harder for some readers to accept fiction’s truth value.

In nonfiction, when you work with archives, people are willing to grant you from the very get-go a certain kind of authenticity, a certain kind of veracity, a certain kind of authority that they may not grant fiction. But you’re also not allowed as much freedom of movement in nonfiction unless you’re willing to do the equivalent of breaking the fourth wall. I am wondering if that’s possible. Why not? Why not introduce fiction into your scholarship at a certain point? There are certain scholars who have done that—and I’ve read some of these works that I find really interesting—but that’s not the mainstream of nonfiction or academic scholarship. And I’m not interested in the mainstream. I’m interested in the essential works that are at the margins or that try to cross over.

In Nothing Ever Dies, you argued that wars are fought twice, once on the battlefield and then again over their memory. The Vietnam War continues to reverberate through American culture since that book’s publication, recently for example in Spike Lee’s Da Five Bloods or HBO’s The Watchmen. Have recent attempts to turn the war into a usable past broken any new ground?

The energies around the Vietnam War are still with us. If anything, the rise of Black Lives Matter and these new social movements on the streets are the sequel to what happened domestically in the 1960s in the United States. From a foreign policy point of view, the Vietnam War still remains lodged in the American consciousness because that war was not just about Vietnam. That war has to be understood as one episode in a century’s worth of war that the United States has fought since the Philippines to achieve global domination through the Pacific, and now the West that has gone all the way around the world to the Middle East.

What the Vietnam War represents is the failure of that American ambition, or a rupture in that American ambition, that Americans are still trying to recover from; the forever war that we’re engaged in now is simply an extension of the Vietnam War. I think the Vietnam War will continue to remain resonant in the American consciousness for even longer. As long as the structure of our society stays the same. As long as we’re still a military industrial complex committed to putting our military all over the world.

And if the narratives that Americans use to make sense of their wars remain the same, then the Vietnam War will still keep returning. That’s what happened with Da Five Bloods. It’s got an anti-racist critique from the perspective of Black men, but because it’s so deeply invested in American narratives of the Vietnam War—whether we’re talking about Hollywood narratives or the “war is hell” narrative—it can’t escape from this American imaginary. It cannot understand what the Vietnam War’s real meaning is for the United States, and therefore it cannot really understand the place of Black men in this history and in this experience. So there will continue to be repetition in the dominant mainstream American imagination, and by that I mean both white and now Black understandings of this war. Michael Mann has apparently finished shooting his epic TV series about the battle of Huế. I am nervous about that. I doubt it’s going to be divergent from anything I’ve described.

And yet because the rupture of the 1960s did produce a rupture in the American consciousness, there is more critical awareness of some of these kinds of issues, which is why we can have Black Lives Matter now. There is an opening for a different kind of narrative or more critical approach both to the Vietnam War and how it connects to the rest of American society. With Watchmen, you basically have a lot of that happening. I have some criticisms, but generally I think the series is trying to connect American imperialism with what we would now call Black Lives Matter. The series is prescient about what’s going on.

There is that possibility. I hold on to that possibility, and I hold on to the fact that we as historians, scholars, and critics have a role in trying to bring that kind of a rupture forward and to provide the kind of narratives that politicians and writers and filmmakers can draw from to produce something more interesting. Because I think that, you know, the people who made Watchmen did draw from both the political rupture, but also the intellectual rupture that took place in the 1960s.

Are there literatures of exile that resonate with you? How much of your writing do you consider specific to your experience as a Vietnamese American, and to what extent do you see the refugee experience as more general or generalizable?

I’m reading Hisham Matar’s The Return, which won the Pulitzer in nonfiction in 2017. It’s a literature all about living exiles and struggling against the Gadhafi regime and imprisonment, political imprisonment, political exile. It’s a beautiful, beautiful narrative that’s also dealing with some really terrible history. Reading it, I was like, well, my life story isn’t as dramatic as Hisham Matar’s, but the general contours of political exile and attachment to a country of origin or homeland resonate strongly. So I think in general, exiles and refugees do understand each other’s emotional experiences.

What is the difference—besides language—between being a Vietnamese and Vietnamese-American writer? Are there different imaginings of, and claims on, the nation?

I can talk about this as a writer and as a person. As a Vietnamese-American writer, I write in English, and I do that because I can’t write in Vietnamese. I would have to spend a lot of time learning the Vietnamese language in a way that would allow me to write literary fiction. When I write in English—not that I have a choice, that’s my colonized condition—if I write in English, I have this strange position, that’s not unfamiliar, of being someone who is colonized, working in the master’s language and getting access to the master’s power because I’m speaking his language. I have no choice but to contest the American canon, this lover’s quarrel with American arts, as A. O. Scott described with Spike Lee.

Because I know the dynamics of all this, I know that if I can test the master in his language, then I can circulate globally in the same way that the master already circulates. That is power that’s not available to Vietnamese writers, most of whom are not known outside of Vietnam. Even when they get translated into a master’s language, like French, they’re still existing in translation. They’re still a minority on the global stage. Whereas I got lucky. I got the Pulitzer Prize, and that has global, symbolic, and real capital as a function of these very complicated histories of imperialism and colonialism and racism. By virtue of my position, I participate in all of that, and it’s a privilege that’s a very conflicted privilege versus a Vietnamese writer.

Answering as a person, I’ll say that I once had a young Vietnamese woman get very angry with me for referring to “Vietnamese people in Vietnam.” She wanted to know why I would say that. To her, when you say Vietnamese people, you mean the people who live in Vietnam.

From my position as an overseas Vietnamese or as a Vietnamese American, these are very conflicted issues because in the United States, Vietnamese people will say they’re Vietnamese, but they won’t say Vietnamese American. The younger generation does, but I grew up with Vietnamese people. We just said we’re Vietnamese. To me, there is a real distinction between Vietnamese people in the United States and Vietnamese people in Vietnam that needs to be drawn out that Vietnamese people in Vietnam don’t see. It’s still a very conflicted relationship in a lot of ways, because we Vietnamese people in different countries live in parallel tracks that don’t necessarily intersect.

Especially if we talk about Vietnamese Americans versus Vietnamese people, you know, there’s a lot of historical emotional baggage and complexities that come along with this—a lot of misunderstandings and resentments and suspicions and love and intimacy that binds us all together in ways we may or may not want. I don’t know if I will ever solve that conundrum. And that is the way by which history still continues to ripple through my life.

If Vietnam is one place that has shaped you in some way, California is another. Do you think of California as character or backdrop?

California is definitely a backdrop for a lot of the work that I do. And I think, for example, of Susan Straight, who, you know, also takes California as a backdrop in her memoir, In the Country of Women. When I read that book and the rest of her work, I thought, this is not California boosterism, and it’s not the California of Joan Didion. There are many Californias there. And this is not the California that New Yorkers want to want to write about when they come over here.

That’s the kind of California that I’m interested in, the kind of California that Susan Straight grew up in, in Riverside. The California that I grew up in, in San Jose. The California that no one talks about unless we ourselves talk about it. The California of people of color, the California of the working class, the California of refugees, the California that does not make it to Hollywood, even though Hollywood is in California. It’s all these people who are erased from Hollywood stories who live in this state. That’s the California that I’m interested in.

Can you say something about your writing process? Do you have different habits for fictional and nonfictional writing? Do you revise?

It just depends. With The Sympathizer, because the language of the novel was so important, I revised as I went along, so I wrote a chapter or twenty pages and then I would immediately revise it. Before I went to the next chapter, I felt pretty comfortable with the language of the previous chapter. It took about a month to write a chapter writing full time while I was on leave.

The book that I’m writing now is nonfiction. It’s a mélange of different things, and the style is different. It will not be as dense as The Sympathizer. If anything, it draws more from Twitter as a form of writing. Also, I’m living in a different time period: I have kids, there is COVID, and I have to teach in a few weeks. This book has to be finished before the sequel to The Sympathizer comes out because I will have to promote that book. Thus, I’m just writing this one as fast as I possibly can. I’m not worried about the quality of the prose at this stage. I just need to put words down and write it as fast as possible.

What kind of historical stories do we need more of right now?

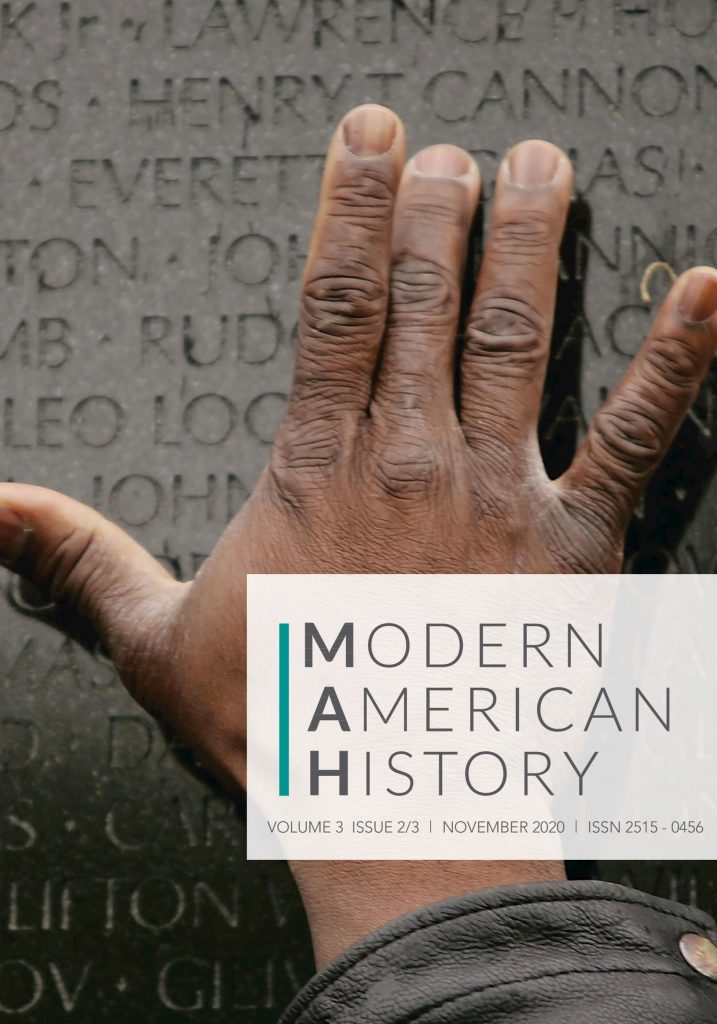

When you ask me that question, I think there are so many, so many possibilities. One of the things I thought about in writing Nothing Ever Dies is the fact that the book focuses a great deal on memorialization and monuments, and one can go out and look at the memorials and monuments to atrocities, to the dead and all that. But the reality of it is that most deaths are not memorialized, and there are wide swaths of history where people have died in places where there are no markers.

Maybe as humanists, we would like to think everybody’s story gets told, that justice will always be realized. Yet, I have to think there are probably whole populations that have been wiped out whose stories have never been recovered. That’s just the reality. There’s probably more that’s been not memorialized, not told, than the reverse. Which is to say, if you do your library research and 100 books come up on your topic, you had better be doing something so unique that there’s a real reason for it. Otherwise, maybe write something else. I, for example, have had a hard time writing about San Jose of the 1980s where I grew up. There aren’t that many books, as far as I know, about San Jose of the 1980s or 1970s. Not that many books about San Jose period, so why did I not think that San Jose was a worthy topic? Writing this nonfiction book now, I made it partly about my San Jose. There are so many histories like these that need to be told and recovered.