Viet Thanh Nguyen speaks with Jinwoo Chong about anti-Asian sentiments, writing, and the publishing industry for Columbia Journal.

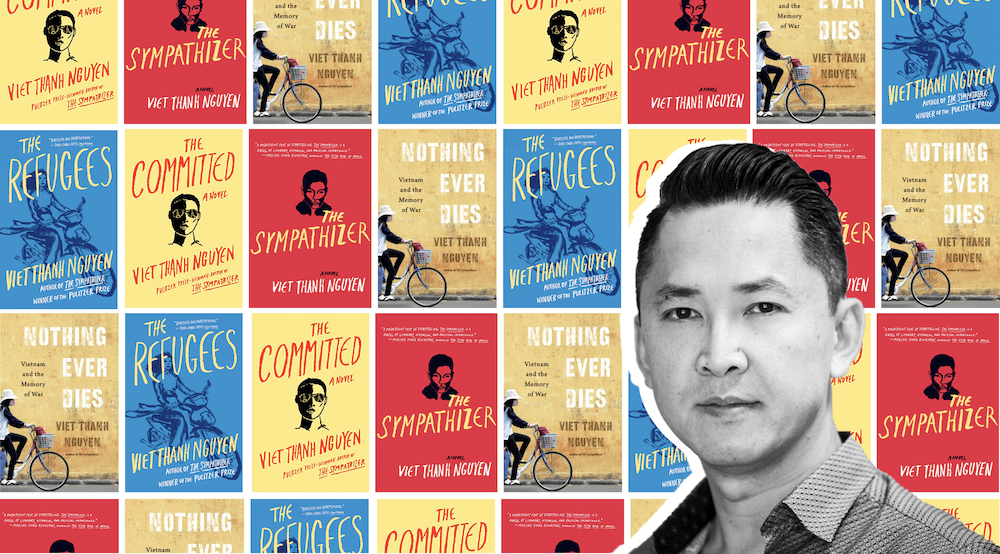

Jinwoo Chong, online editor at Columbia Journal, spoke with Pulitzer Prize-winning writer Viet Thanh Nguyen, author of The Sympathizer, The Refugees, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and The Memory of War, and Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America, and the fiction judge of the 2020 Columbia Journal Winter Contest.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Columbia Journal: We’ll start with what has become something of a required question these days, given COVID and the current state of the world, which is: how are you doing?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: It’s been difficult for everybody. I think, in general, I’ve been fortunate because I have a place to weather COVID and I can go out and take walks. But I also face the same challenges that many others confront, such as having kids at home, having an aging father 400 miles away, and so on. So no doubt, it’s an added layer of stress. I’m also writing a nonfiction book, and COVID, of course, is there in the background. All these questions around isolation factor into the book. I’m also thinking about the impact of COVID and what it reveals about our country and the rest of the world—inequalities that are structural and deep. The nonfiction book talks about me but also about these political and economic problems of inequality and injustice. So for better or for worse, COVID has turned out to be an opportune moment. It’s terrible for the entire country, but for a writer, terrible moments can be good because they provide a lot of material to think and write about.

CJ: Thinking about the inequalities that COVID has revealed in America brings to mind recent acts of discrimination and violence toward Asian Americans, goaded by Donald Trump’s use of terms like “Kung Flu” and “Wuhan Virus.” An essay on this issue by Cathy Park Hong in The New York Times Magazine was titled “The Slur I Never Expected to Hear in 2020.” You’ve written extensively about the experience of Asian Americans in the United States. Do you see these recent racist acts as much different than what Asian Americans have endured throughout American history or is it more of the same?

VTN: I don’t think there’s anything new about it. If you go back to the nineteenth century—talking specifically about Chinese immigrants—they were faced with intense anti-Chinese hatred which amounted to events including lynchings, for example. They were subject to all kinds of violence and discrimination that were worse than what’s happening now. I think what’s happened, though, is that because of the passage of the Immigration Naturalization Act of 1965 and the creation of this idea of Asian Americans as a model minority—which is a relatively recent phenomenon—combined with the fact that most of the Asian American population today has come into being after 1965 and the worst of anti-Asian violence, it means that for today’s Asian Americans, these racist acts are a real shock. I think many people thought that anti-Asian violence was a thing of the past or something they had never even heard about before, and so to encounter this now is very painful and terrifying for many. But hopefully, it’s radicalizing for some and getting others to at least think about the long history of anti-Asian violence that already exists in this country. These anti-Asian sentiments are waiting to be reawakened, as with every other racist component of American history, because we, in fact, are a country in which racism is part of our DNA. It structures almost every aspect of our lives, and for different populations at different times, the racism directed against them goes latent or submerges below the surface because other issues take the foreground. So for Asian Americans in the last thirty, forty, fifty years, the feeling has been well, we’re not really the victims of racism because we’re not Black or brown. Asian American attitudes towards that differ but I think that’s pretty much the sentiment of many Asian Americans. It’s an unequal terrain because if you happen to be a poor Asian American in an urban environment, you are oftentimes subjected to anti-Asian violence and prejudice. However, for Asian Americans overall, especially the ones whose voices are ultimately heard, racism hasn’t been a factor in their lives. But again, it’s always been there, latent, ready to be reawakened at any moment of crisis in which Asians are situated as a threat to the United States, and of course, Trump has made that threat quite visible.

CJ: How would you envision teaching these recent events in a class about Asian American history?

VTN: Cathy Park Hong’s book, Minor Feelings, which set the groundwork for that essay in The New York Times Magazine, is a great read and a book that taps into her own anger as well as the anger and suppressed rage of a lot of Asian Americans. That, in conjunction with my own history of rage and the anger I’m feeling in this moment of COVID that we’re in, means that my nonfiction book that I’m writing has a lot of rage and anger while talking about the same kinds of issues.

The next time I teach an Asian American studies class, I’m definitely going to teach Cathy’s book. I think it’s completely relevant and weaves together so many critical issues of Asian American culture, history, and politics to the personal and the autobiographical.

But I have to say, honestly, I’ve been dealing with Asian American issues since I was 19 at Berkeley. My trajectory has been that first, I was sort of a convert to the Asian American cause, believed in it deeply, and then dealt with it for a few decades. Then, I got tired of it because there’s a lot of Asian American thinking and work that is insular, self-congratulatory, and dominated by neoliberalism on the one hand and by a self-congratulatory radicalism on the other hand. So, it was actually a relief not to have to teach Asian American studies in the last couple of years at USC.

But now I think with COVID and the rise of anti-Asian violence, I feel slightly more rejuvenated and I’m exploring the possibility of going back to teaching [Asian American studies] again but from an even angrier perspective than I had before. A perspective that is much more free and gives reign to being critical of Asian Americans. The standard strand of Asian American thinking is to embrace the reality of anti-Asian violence and rhetoric and to say that we have to be critical of anti-Asian racism in the United States and everything that it’s connected to—which is absolutely true. But our current moment has also made clear that there are lot of Asian Americans out there who are also racist; who accept the inequalities and injustices of American society because it benefits them; who are perfectly ready to spout anti-Black, anti-Latino, anti-immigrant, and anti-refugee rhetoric; and who are willing to embrace the military industrial complex and the use of American power overseas. This is deeply problematic.

It is up to Asian Americans to criticize fellow Asian Americans when they say and do these kinds of things. That has to be a key component of anything we do as Asian Americans. If I were to go back and teach Asian American studies in the next year or two, it would be to discuss both of these realities. Anti-Asian violence is something to put in the foreground, but the question of Asian American complicity is not something that we can simply put aside.

CJ: To pivot towards some of your work, we now know that The Committed, the upcoming sequel to your 2016 novel, The Sympathizer, is due to be published next year. Did you envision this story as larger than one book from the outset?

VTN: When I set out to write The Sympathizer, my intention was for it to simply be one novel, but it was very clearly conceived to be a novel that incorporated many genres, including the spy thriller. When I finished The Sympathizer, I thought: I’m not done with this character, I’m still interested in him, and he’s still alive. What’s very clear by the time you finish reading The Committed is that the story’s not finished yet. There’s still at least one more story. I’m not done with him because, from the perspective of the plot, I think there are still some interesting things to put him through. This character goes through a lot in The Sympathizer but goes through even more in The Committed, which is all good for the reader because a suffering character is dramatically interesting. I also think there are various kinds of theoretical political issues that The Sympathizer brings up that I had not finished exploring. As an Asian American writer, I’m not interested in just telling the story, although telling stories is important. I’m also interested in working out theoretical political issues in the fiction. I think of The Sympathizer as a dialectical novel, and in finishing it, I decided I needed a dialectical trilogy because the issues the book raises, in terms of colonialism, race, and war, I only got part way through parsing. There were also the politics of gender, sexuality, and heterosexuality that I needed to continue working through. That’s the terrain of The Committed. It continues the conversation of race and colonialism in Paris and in France and confronts a different kind of imperialism than American imperialism.

CJ: For a period of time before writing The Sympathizer, you primarily wrote short stories, many of which were anthologized in your collection, The Refugees. How did the transition from short fiction to novel come about?

VTN: I’d always wanted to be a novelist. I never thought about being a short story writer until I got to college and discovered that short stories were a thing. In writing workshops, that was the preferred mode by which the writer learned to write. I wrote short stories as my mode of apprenticeship in writing. I thought they would be easier to writer than a novel because they’re short, which, of course, was a false belief. Writing short stories was a completely miserable experience. It took 17 years to write 95% of The Refugees and then 3 more years to finish the last 5% and to get it published. It took 20 years altogether, and I have to say, 99% of it was miserable and terrible. There was no joy in it. A lot of readers like the book. They enjoy it and read it pretty quickly, which is not the way it was written. But pounding my head against the wall for 20 years with that book meant that somehow I had broken through and learned how to write without really understanding how. It was a matter of practice. I go back to that image in The Karate Kid where Daniel LaRusso learns the basics of karate Mr. Miyagi by painting a fence and waxing a car, and then all of a sudden, he finds that he can block a blow. That was what it was like for me. After writing many short stories, I found I could write a novel.

CJ: It’s safe to say, The Sympathizer is an enormously influential work of Asian American literature. It’s critically lauded and taught in Asian American studies classes at major universities. How does it feel to see your work reach those heights?

VTN: I’m certainly very grateful for that and pleasantly surprised. I, too, was once an undergraduate student enrolled in Asian American and other minority-specific literature courses, who was thrilled to read books by Asian Americans and other writers of color. Though I’ve always wanted to be a writer, I don’t think I ever fantasized that one of my books would be included in syllabi. It’s obviously a great thing to know that there are people teaching these books.

In terms of wanting to be a writer, I had a lot of fantasies in general about what that would be like, as I think most people do. You have certain idols and certain dreams about what you can accomplish. You want people to read your book and you want to win prizes, Not everybody wants these things, but I think a lot of us who are subject to human vanity and frailty, as I am, have these fantasies. So after 20 years of suffering to be a writer, I reached the moment where I felt: this doesn’t matter anymore. That was absolutely liberating. I think a lot of writers go through this. The moment a writer gives up on other people’s expectations, human frailties, vanities, and desires and just writes the book that they want to write, regardless of circumstance, that’s the moment they really become a writer. So then, The Sympathizer is successful, wins prizes, is included in syllabi, and part of me shrugs and says: that’s nice. I’m happy and grateful, but it’s not really what it’s about. It’s an interesting situation to be in, where, by the time the accolades come in, I don’t really care that much about them anymore. It’s a good place to be as a writer. If you care too much, it’s a miserable experience.

CJ: As our Winter Contest judge, you’ll be looking at our finalist short story submissions. Are there certain aspects of short stories that you are drawn to, and conversely, are there aspects of short stories that would cause you to automatically dismiss them?

VTN: In general, no. People can turn to a recent issue of Ploughshares that I edited for evidence of that. I chose a variety of stylistic approaches to fiction and nonfiction. I think, in the end, it’s really just a matter of whatever moves me. Whatever works. But I will say that my approach to the Ploughshares issue was to be very attentive to the identities and backgrounds of the writers who I ultimately chose for the issue. Artistic merit aside, I think editors have an obligation to be aware of representational problems, especially within the history of their own journal, but also within the history of the field. There’s plenty of evidence that the literary industry is not immune to the problems around race, diversity, and inclusion that are endemic within American society. Statistically, the publishing industry is about 84% white, and when you see what small literary magazines publish and who’s on their mastheads, you see the whiteness. And so, you can look at the Ploughshares issue to see that I’m very careful about trying to be demographically inclusive, and that, in itself, it is a political statement but also a literary statement. I got to choose half the writers right off the bat; almost everybody I chose was a person of color. The publishing world works in layers. There are so many moments of selection and gatekeeping, and the people who are manning the first gates are oftentimes young and unquestioning of their assumptions. There’s so much work to be done in terms of making people aware and sensitizing them to their own prejudices and those of industry as a whole. Being a guest editor is an important job. It’s probably better that we have diverse editors of color permanently staffing journals in the publishing industry, but in the interim, those of us who are concerned can play our role in trying to introduce differences the best that we can.

CJ: Dovetailing with this was an interesting viral moment on Twitter in which authors of color tweeted the exact amount they received as an advance for their books.

VTN: I participated in this. My advance for The Committed, after I won the Pulitzer Prize, was frankly still smaller than the first-time advances for a lot of unknown white writers. My advance for The Sympathizer was $35,000, which is not that bad in the literary world, but small when compared to the $2 million advance that Garth Risk Hallberg got for City on Fire, which was the big debut novel of that year. I don’t know how the hype mechanism works for why certain books get these six and seven-figure advances. Sometimes it can work to the benefit of writers of color. Obviously, some writers of color do get the hype as well, but disproportionately so. We need to examine the role that prejudice plays, even if not explicitly, in who gets published in journals. People of all kinds who are subject to their own unexamined tastes and prejudices are selecting what gets published, including myself. So I have an Excel sheet where I track the writers I’m reading: how many Americans and non-Americans, how many white people, how many people of color, how many men or women, trans or non-binary, just so that I know where my interests are falling. I’m reading more works by people of color than white people, but I’m reading twice as many American writers than non-American writers. The same thing has to happen in the publishing industry. People have got to keep track of statistics. And works by writers who are clearly from non-white, non-privileged backgrounds need to get second looks.

CJ: A popular statement from the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg goes: “When I’m sometimes asked when will there be enough [women on the Supreme Court] and I say, ‘When there are nine,’ people are shocked. But there’d been nine men, and nobody’s ever raised a question about that.” If, say, the longlisters for the Booker Prize were all Asian, or all Black, and so forth, would this be a good thing, or would we be going too far?

VTN: Right now, you could clearly have longlists for the Booker Prize and short lists for the Pulitzer Prize that are all women. I don’t think that would be a problem. I think Ginsburg is correct in that regard. Women make up probably half or more of the authors being published as well as the population consuming these published works.

A list of only Asian American or Asian or Black writers and so on: why not? It just probably depends on the criteria. The Pulitzer Prize is for American writers, and Asians are only 6% of the American population, so maybe it’s a little hard to justify the whole shortlist being Asian Americans. The Booker Prize, on the other hand, represents the Commonwealth. That’s all the English-speaking countries that the British colonized! Let’s talk about that! And if you have prizes that include translations… the majority of the world’s population is people of color. Why can’t you have an entire longlist composed of Asian international authors if your prize is that capacious in its criteria? So, yes, once you start talking about these things, the absurdity of having a shortlist that’s all white men becomes very clear.

CJ: What advice would you give young writers during this time of upheaval, both in the world and the publishing industry?

VTN: The conditions under which we’re writing are extreme for Americans but not extreme for much of the world much of the time. In the past, people have written whole books sitting in a prison somewhere for crimes they should not have been convicted of, due to racism or colonialism. Women have had to write books while taking care of their families that their husbands were neglecting. When you think about these kinds of issues other writers have faced, you realize being confined to your room is not the worst possible thing that could happen to you. And for some people, it may even be a good thing. They can live their isolated lives in ways that they would have anyways but is now seen as the norm for everybody else. There is much to be sympathized for people who are debilitated by poverty, the lack of resources, and mental illness, and living with abusive people in their families or households. But outside of those circumstances, I think writers need to simply confront our isolation with our own words and our own thoughts. It’s basically what a writer does, at least those of us who have the mental and emotional and financial resources to do so.

Writing The Refugees really was 10,000 hours of sitting in a room by myself. That’s the reality for writers. With all the apologia and exceptions for people who are finding it difficult psychologically, emotionally, and financially during this time, this is a test for writers: can you still produce under these kinds of circumstances? Any kind of writing is alright. I’m working on a nonfiction book in spurts, but I take time off to write Facebook posts and Twitter posts. You might think that’s just social media, but, in fact, I think of them as rough drafts of ideas for other things. Everything is a form of writing. Think about your writing persona as one that is complete. A person whose every act of writing is a part of their writing persona. Every moment of writing is an exercise of who you are as a writer. We may not know how this COVID era and our social media habits and interaction are going to impact us as writers as a whole but try to embrace it. Try to make something useful out of what’s been forced upon all of us.

Submissions for Columbia Journal‘s 2020 Winter Contest will open in all categories on November 15, 2020.