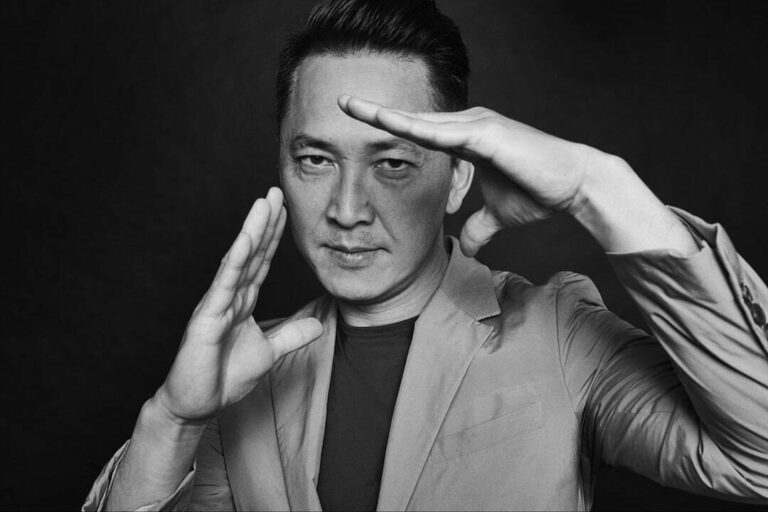

Viet Thanh Nguyen captivates the audience of students at Lake City High School auditorium and talks about identity struggle, privilege, and power.

The slow, steady pace of Harrisburg, Pa., resting along shallow canyons carved from the easy turns of the Susquehanna River, represent a crossroads in Americana. Reminders of the Colonial age meets what’s left of the Industrial Revolution. East meets the Rust Belt. Quiet days lie ahead for those who move here and choose to call Harrisburg home, if they’re willing to make the trip.

The trip wasn’t a choice for Viet Thanh Nguyen. He was one of the fortunate few refugees to escape Vietnam in 1975 as the country of his birth was toppled by a Communist regime. For him, Nguyen said, Harrisburg was a last chance to escape. From his Pennsylvania home to California and its university in Berkeley to his assistant professorship at the University of Southern California, Nguyen lived a different American life than natural-born citizens might live.

But it’s an American life nonetheless. He encapsulated the dual experience of that life as a narrator fighting for two homes in his 2016 novel “The Sympathizer,” an acclaimed piece of literature that follows an agent for the North Vietnamese Army living in the United States. The novel earned Nguyen the Pulitzer Prize. He shared his experience grappling between two worlds with an attentive young audience Friday at Lake City High School.

“I loved books when I was your age,” he told the auditorium of Lake City and Coeur d’Alene High School students. “As a refugee in a camp in Pennsylvania, I came to Harrisburg not having any bearing of who I was. I ended up using books as a refuge, as an escape.”

The symposium between Nguyen and the students, sponsored by the Idaho Humanities Council and Idaho Forest Group, was the latest in a noteworthy line of forums between impressionable local minds and award-winning authors. John Meecham and Doris Kearns Goodwin, both Pulitzer Prize winners in their own right, have come to Lake City High for previous Humanities Council-driven conversations with students. The keynote speaker later that night at the Coeur d’Alene Resort made a point to connect with students and share his most formative years in most Americans’ lives: their time in high school.

“My experience in high school was basically, it sucked,” Nguyen said, earning empathetic laughs, understanding head-nods and an auditorium of student buy-in.

The hour-long stop at Lake City began with Nguyen sharing his struggle with identity, living in a culture that opened its doors to him but didn’t quite embrace him. He said he was constantly surrounded by a culture he didn’t recognize and a culture that didn’t recognize him.

“Who here knows who this is?” he asked the audience, opening his sweater and exposing an image of Bruce Lee on his T-shirt. After a moment of awkward silence, he continued. “… Growing up, this was the only positive role model I saw on television that looked like me. The few other people on television and in the movies that looked like me were caricatures you were supposed to laugh at or fear. People who look like me would get upset when they saw people like Long Duk Dong [a character in Sixteen Candles played by Gedde Watanabe] representing us. And everyone else in school would say, ‘Dude, what’s the big deal? It’s just a story.’”

That was when Nguyen said his love of books was justified.

Stories matter.

After Nguyen shared his thoughts on privilege and power, he began a question-and-answer session with moderator Mike Kennedy and with the audience, where he leapt into the crowd to engage with students.

“I don’t know what I would have been if I stayed in Vietnam,” Nguyen answered to a Lake City student. “My brother was a valedictorian and…went on to become a doctor. I think that probably would have been my path.”

After answering questions about Vietnamese culture, his trip back to the land of his birth and his thoughts on today’s worldwide refugee crisis, Nguyen said the mythology of a refugee as a grind against America is one that endures today, illustrating his point with a situation that unfolded in that Pennsylvania camp in 1975, where a friend of his family allegedly murdered another refugee in the camp.

“The guy who committed murder didn’t kill someone because he was Vietnamese,” he said. “He killed someone because he’s human. My brother wasn’t a valedictorian because he’s Vietnamese. He was a valedictorian because he’s human.”

“I thought this [symposium] would be different,” Coeur d’Alene High School Junior Ty Betts, 17, said after the event. “I thought this was just going to be something sad and hard to listen to. But it was great. It was a real learning experience…One lesson I learned was: Accept other people. You don’t know what they’ve gone through, you don’t know who they are, and you can find a common ground with people if you just listen.”

Asia Heston, a 16-year-old Lake City High junior, said she was moved by Nguyen’s talk.

“I didn’t have any idea what to expect,” she admitted. “Once I sat down and started listening, I was really drawn to what he was saying. My grandma was a refugee from Vietnam, so I kind of got to hear her story while listening to his.”

Despite the personal struggles and hardships, Nguyen said his family’s fortune wasn’t lost upon him.

“Vietnamese were allowed into this country at the time because we suddenly were considered exceptional,” he told the students. “Ours was supposed to be an exceptional culture that produced exceptional people. Let me tell you: I’ve lived in the Vietnamese-American culture. We are not an exceptional people. We were not exceptional. We were just really, really lucky.”