Thy Vo discusses refugee writers and The Displaced by Viet Thanh Nguyen in this article for The Mercury News.

OAKLAND — Amid a national debate over the country’s policies toward immigrants and deportation policies, a group of panelists spoke of the complexity of being displaced and struggling for identity in the country they sought refuge.

A collection of essays, titled “The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives” seeks to give voice to the experience of being forced to leave one place and seek a home elsewhere, and challenge the political identity given to refugees by virtue of being unwanted.

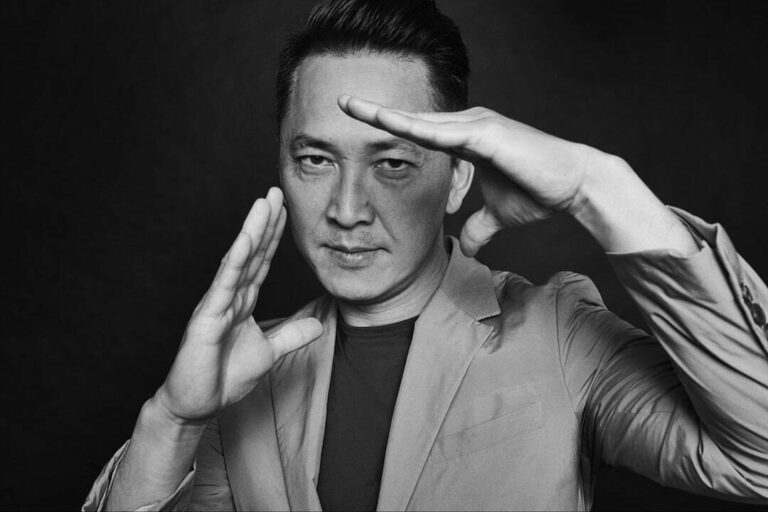

“One of the ways refugees become stigmatized or dehumanized is their voices are taken away from them,” said Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author who edited the collection, at a panel at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center Sunday. “They end up becoming spoken for and objects of pity.”

The collection includes stories of loss, struggles with identity and the scars of displacement, from authors originally from Mexico, Bosnia, Iran, Afghanistan, Ethiopia and other countries.

“It’s important to have refugees … not prove our humanity, but we assert our humanity,” Nguyen said.

The United Nations estimates there are 68.5 million forcibly displaced people worldwide — 40 million people displaced within their own countries and 25.4 million refugees, defined as people who have been forced to flee their country because of persecution, war or violence.

In his essay “Last, First, Middle,” Joseph Azam tackles his youthful unease with his Afghan identity and birth name, Mohammad Yousuf Azam.

He changed his name to Joseph after moving to California at 15. Growing up, he and others around him discussed their identity as Americans and immigrants but not their identity as refugees.

“I think a lot of my life was engineering how to pass, how to be white-passing, American-passing,” Azam said. “What’s happened recently is I’m realizing that has not gotten me very far. When I land at SFO, people see … place of birth, and Mohammad, and that’s an extra 20 minutes.”

Azam is a corporate attorney and former executive for News Corp., the company which owns Fox News Channel. He quit his job at News Corp. over the network’s coverage of Muslims, immigrants and race, and described publishing the story as a healing process.

“One of the things for my journey is recognizing once a refugee, you are always a refugee — there is no arrival,” Azam said. “I’m always having left somewhere.”

Nguyen, who was born in South Vietnam and fled his hometown as the Vietnam War came to a close, drew comparisons of his own experience to migrant families who are separated at the southern border.

Nguyen’s family ended up at the Fort Indiantown Gap refugee camp in Pennsylvania. They could not find a sponsor willing to take their entire family, so they were split in three, with one sponsor for his parents, one for his 10-year-old brother, and one for Nguyen, who was 4 years old.

“It was meant to give my parents time to get on their own two feet … but 4-year-old me saw it as being abandoned or taken away from my parents,” Nguyen said. “And that’s how I know the policies we’re carrying out at the southern border … are going to scar those children forever.”

He challenged fellow Vietnamese refugees who argue the country should not accept additional unauthorized immigrants or refugees.

“There are some former Vietnamese refugees out there who say we should not take in any more refugees because these are bad refugees, and we Vietnamese were the good refugees,” Nguyen said. “I grew up in San Jose in the 1970s and 80s — and let me tell you, there were some ‘bad’ refugees.”

Nguyen referenced a rise in crimes like fraud and home invasions, committed by Vietnamese immigrants after the war ended.

Telling refugee stories requires that we acknowledge the complexity of people, good and bad, Nguyen said, including atrocities people may have committed during wartime.

Moderator Michael Tran asked panelists how they pursued their own career paths in families where, after having taken so many other risks, there is cultural pressure to pursue stable, high-paying jobs like a doctor.

Nkauj Iab Yang, a Hmong American, grew up in the Del Paso Heights neighborhood of Sacramento, one of the poorest neighborhoods of the city where she remembers feeling angry about economic inequality and the lack of resources for her neighborhood.

Her decision to become an activist and organizer, and fighting with her parents for her freedom to do so, was essential to her growth, said Yang, policy and programs director for the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center, a nonprofit advocacy group for refugee communities.

“You cannot wait for somebody else to do what it is you are envisioning. You have to be the one that ensures that comes to fruition,” she said.

Yang said what has helped her mother, who doesn’t fully understand her work, accept her path in life is her active role in their family.

“Whatever career I choose, I’m always going to come back home,” Yang said.