Johanna L. Añes- de la Cruz talks with Viet Thanh Nguyen about memory, trauma, and storytelling for ABS CBN News.

MANILA — Viet Thanh Nguyen was only 4 years old in 1975 when his family fled Vietnam to the relative safety of the United States.

It was his life as a refugee and being surrounded by countless others like him that would eventually and inevitably influence and inspire his body of work, now among the most highly regarded in contemporary world literature.

Talking to ABS-CBN News during the 2019 Philippine Readers and Writers Festival organized by National Book Store, Nguyen opened up about growing up as a Vietnamese refugee in California, confronting darkness, and the power of stories in these often turbulent times.

Being only a little boy when his family fled strife-torn Vietnam, Nguyen admitted not remembering anything during their flight to the United States.

“My memories really started once I got to the United States, to the refugee camp in Pennsylvania. My memories before that time period were very, very unreliable so my brother who is seven years older would tell me we were actually in the Philippines. We transitioned, I guess, through one of the military bases here, but I have no memory of that,” he said.

He continued: “Things started to cohere once I was taken away from my parents and put with an American sponsor family, because you need to have a sponsor in order to leave the refugee camp. So for me being a refugee is very much tied to memory, how it began with family separation and that has always been a preoccupation of mine in my writing.”

Nguyen considers this separation from his family, even if lasting only a few months, as one of his most indelible memories.

On the role of memory in writing

Despite not having memories of his life before the US, his parents told him many stories of their own traumatic past. “My parents were born in the 1930s, they are basically old enough to remember 30 years of war and decolonization,” he said.

They passed on to the young Viet not only the memories, but also the trauma accompanying these stories.

He intimated an especially traumatic memory told to him by his mother who lived through a famine that ravaged her town in North Vietnam killing a million people. “I never forgot about that because that was a huge number of people especially for that time period. Imagine you’re this little girl, she was 6 or 7, and for her to have memories of that and to transmit them to me. I never forgot that,” he said.

But memory transcends the personal and the familial as it seeps into both the social and the collective. As Nguyen shared, “For those of us who have been impacted by history, oftentimes, the way we were impacted is not necessarily through our own memories, but through the memories of the people right next to us. It’s very common that for people who have lived through some kind of traumatic history like my family, even if I don’t remember the past I‘ve witnessed my parents being affected by this past.”

Nguyen admitted how these memories have “shaped everything that my parents have said and not said, done and not done and that has an impact on me.”

Sometimes the memories are explicit, such as when his parents talked about them. But there are instances wherein the memories are implicit, tucked into silences and erasures, in things unsaid, actions left undone. “When things are not spoken of, it doesn’t mean they’ve been forgotten, sometimes the things that are not spoken linger in the air and shape the way that people behave,” he reiterated.

Nguyen then spoke of the daunting task of investigating memories, not just his own, but of the greater Vietnamese refugee community, who despite putting on a brave front, most haven’t moved on from their harrowing past.

“Part of the difficulty of the work is looking for the traces of memory that are actually not spoken,” he admitted. “For example, in the Vietnamese refugee community there’s a lot of violence, domestic violence, crime that don’t seem to be explicitly related to the war, but of course, they are. The ripples of history have impacted all of us. That’s part of the work on memory that I’m engaged in.”

On writing about difficult issues

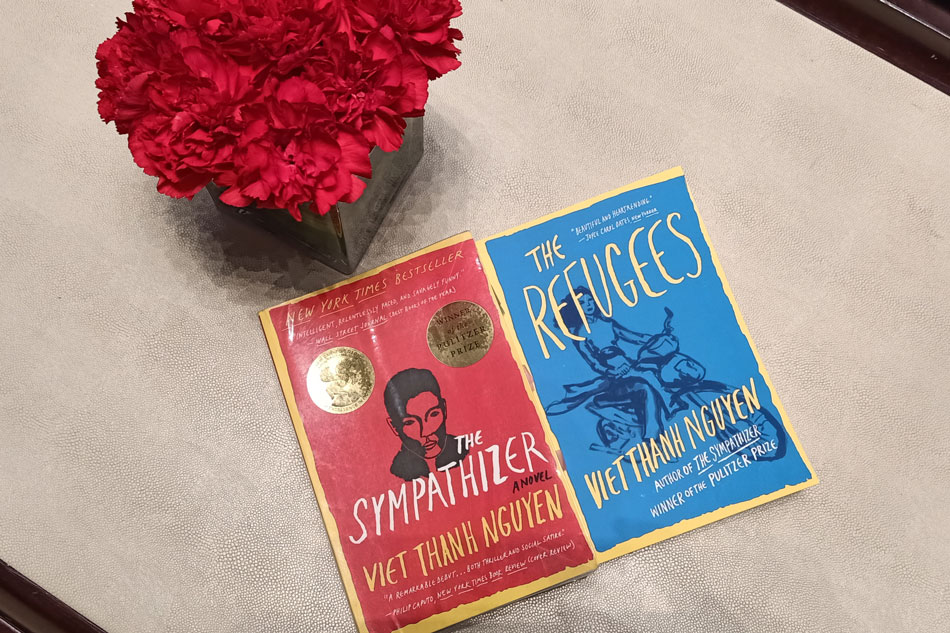

All of Nguyen’s major works including the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Sympathizer” (2015) and his collection of short stories “The Refugees” (2017) have tackled the Vietnam War and topics surrounding it.

“Being a refugee, having lived through a war and shaped deeply by it and its impact on my family, I really wanted to deal with these topics around the Vietnam War. I needed to get this out of my system first before I do other things,” he said.

Nguyen and his family had gone through some very dark moments in their lives, so when asked about how writers could handle difficult, even traumatic, matters, he suggested being ready to confront darkness, both historical and personal.

“I think that when we write about difficult issues we have to be ready to go into dark places — both historically and personally. Historically we have to be able to look at situations in which terrible things have been done, we have to look at the people who have done those things and the people to whom those things have been done. I have done a lot of that because I have written another book, a nonfiction book (‘The Refugees’) on Vietnam, the war and memory. It is a very depressing book to write because for 10 years I was going to Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia to look at all these war sites. You have to brace yourself for that,” he said.

“The other thing that’s difficult is looking at the darkness within yourself. I think that the only way that these things can have meaning for us is not for us to think that these are events that are far removed from us, that these terrible things were done to people who are far away from us and that the people who did these things are monsters. It’s not true for the most part. For the most part the things that were done were done by people just like us and if we ourselves are in these situations maybe we would do the same things and for many of us, if it wasn’t us, it was our relatives,” he continued.

He urged writers to think of history not as something that is removed from our lived realities, rather something with which our lives are deeply entwined.

On the power of storytelling

Nguyen emphasized the power of stories and how storytelling will always matter.

“I come from the US and Donald Trump is a master storyteller,” he said.

He clarified, though, that while he doesn’t like his stories, he cannot deny the huge impact of Trump’s narratives, “When Donald Trump says ‘Make America Great Again’ it resonates with 40% of the American population because it’s a story that they feel very deeply.”

“Storytelling still matters for politicians for sure because they tell stories about the country. But then we as storytellers, those of us who are writers, we have an obligation to think about how we tell our stories. We want to express ourselves personally, but I happen to see myself as a writer who also sees his work as trying to have some impact not just personally, but in the country, in the nation as well.”

Nguyen asked that stories be seen not just as stories, but as integral part of our lives, our identity, our country, of the world that we live in.

“Stories are not simply stories in books and movies and so on, obviously they are, but stories are something we live with every day. We tell stories in order to make sense of our world.”