In this article by Soleil Ho for the San Francisco Chronicle, Soleil and Viet discuss enduring colonial fantasies and misbegotten nostalgia over plates of chile wontons and Blue Hawaiian drinks garnished with red plastic dragons.

My name used to give me a lot of grief. France was always an object of fascination for my mother, as a place of unparalleled sophistication and elegance, of haute cuisine and couture. Once I learned more about the history of France in Vietnam, I had trouble reconciling the France in my mother’s mind with the one that had transformed her country into Indochina. My name was a constant reminder of that relationship.

That sense of unease swoops down on me like a large, unruly vulture when I go to a place like Le Colonial, a 25-year-old Union Square restaurant that, in the previous critic’s words, “evokes a tropical French oasis in Vietnam during the 1920s.” What that means is that the courtyard and dining rooms are full of banana trees and birds of paradise, sheer fabrics, rattan armchairs and red lanterns. Ceiling fans circle languorously overhead in the dining rooms.

Upstairs in the lounge, which serves the same menu in a more casual setting, the servers wear stylized qipao blouses and carry drinks poured into ceramic Buddhas to the happy hour crowd. The walls are decorated with framed prints of 19th century ethnographic photos: a man with curled fingernails, a girl with her weaving, a group of topless women in indigenous clothing. Every curve of the hip and every pattern of cloth is revealed for examination. I heard a nearby couple comment on one of the photos, asking loudly, “Are those Africans or Asians?” In a restaurant where diners are prompted to take on the positionality of the colonizer, the vagueness of the photos’ context seems to be by design: These are spectacles to survey from your well-appointed manse in the jungle, not people whose names you need to remember.

It seems odd to think that dinner could be tasty enough to help the bitter pill of colonial fantasy go down easier, but the fact is that the food at Le Colonial is not very good either, full of bone-dry meats, clumsily plated $36 entrees and nigh-undrinkable $15 cocktails.

If I’m going to sit in a place that’s this uncomfortable, shouldn’t I at least be able to get some pleasure out of it? And if the menu isn’t even that compelling, then why does this place exist — and for whom?

Both San Francisco’s Le Colonial and a New York City restaurant of the same name are owned primarily by French restaurateur Jean DeNoyer, though each outpost operates independently. DeNoyer is not alone in applying this aesthetic mode to the restaurant world. In Portland, Ore., a cafe that celebrated British colonization, complete with Winston Churchill-theme brunches, faced protests and a name change in 2016. A “safari-style” restaurant in Brisbane, Australia, inspired similar backlash. In Lyon, France, a bar called La Première Plantation opened (and closed) with much fanfare in 2017; its decor referenced French sugar cane plantations in the Caribbean, and the owners caught flak for calling the colonial period “cool” in an interview about the project.

According to Erica J. Peters, a local historian who has studied the impact of French colonization on Vietnamese foodways, these restaurants must be considered in the context of post-Vietnam War nostalgia for a colonial era, owing largely to the popularity of Marguerite Duras’ 1984 novel “L’Amant” and the 1992 film “Indochine,” which won the Academy Award for best foreign language film. Both dramatize Franco-Vietnamese relations in steamy scenes of lovemaking in sweaty, mahogany-framed environs, with Vietnam personified in a nubile and ravishable young woman in the latter. It’s what Peters called a “Disneyland view of colonialism.”

Shortly after “L’Amant” was published to international acclaim, restaurateur Brian McNally opened Indochine in New York City with a menu of Cambodian- and Vietnamese-inspired items like pineapple martinis and fried spring rolls. “McNally inspired imitators,” Peters said, “notably Le Colonial, which opened in New York in 1993 and in L.A. in 1996, and other restaurants aiming to combine colonial exoticism with French sophistication and high prices.” Following that inspiration, the New York location’s website champions the “seductive spirit” of the era, while write-ups of the San Francisco restaurant often resort to eroticisms, words like “sensual” and “exotic,” to describe the atmosphere.

So why have these restaurants seen such staying power, not to mention acclaim and popularity?

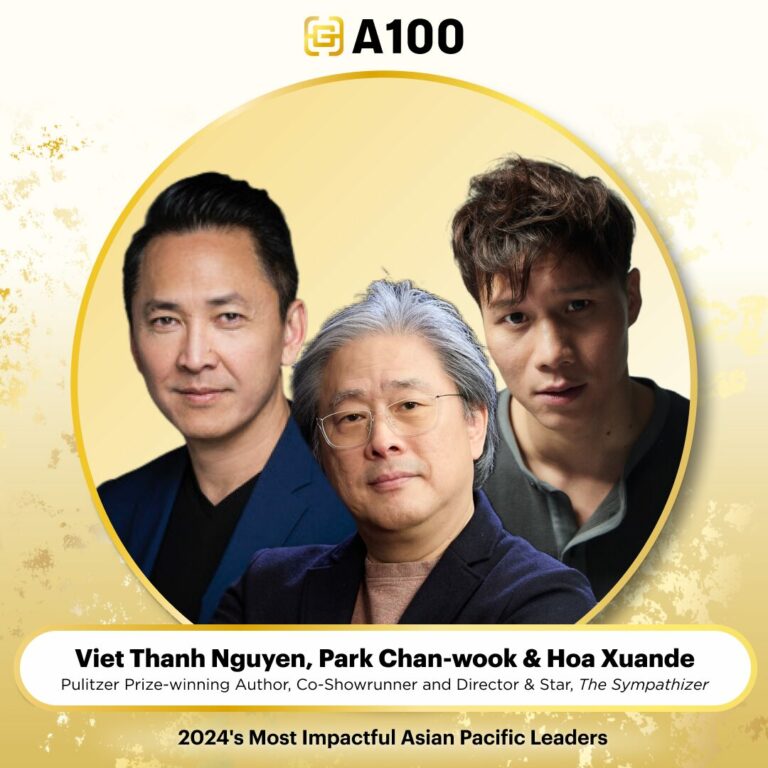

To help explore that question, I met Viet Thanh Nguyen, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, at one of the country’s oldest Far East-theme restaurants: the Formosa Cafe in West Hollywood.

Founded in 1939, the Formosa Cafe is a Los Angeles institution that functioned as an informal home base for the brightest stars in Old Hollywood. This year, it was renovated and reopened with its red lanterns, vinyl booths and chop suey typeface intact. While sipping on towering Blue Hawaiians garnished with branded red plastic dragons and scooping chile wontons into our mouths, we chatted about the appeal of the colonialist.

What might be disturbing for some can be entertaining for others, Nguyen said. In August, he penned an opinion piece for the New York Times that decried the persistence of productions like “Miss Saigon,” arguing that creators could, and should, do better with Asian representation. In that essay, he also wrote that “fantasy cannot be dismissed as mere entertainment, especially when we keep repeating the fantasy. Fantasy — and our enjoyment of it — speaks to something we deeply want to believe.”

People who should know better, whether Asian Americans or those who simply know their history, are just as susceptible to the fantasy that musicals like “Miss Saigon” and places like Formosa Cafe represent. These productions, he told me later, are powered by white people at the most elite levels. “They own the means of production and representation, and as long as they do, it makes it really hard for those of us who don’t own these means to challenge them.”

Instead, we act in them, cook for them and pay them good money for drinks with orchids perched on the rims.

Le Colonial’s theme is covered with the sticky film of racism — but compounding this insult is the fact that the food isn’t well-executed or particularly exciting. Under the management of Saigon-born chef de cuisine Tuan Phan, who recently moved up the ranks from wok station cook to chef after two decades at the restaurant, the menu has more misses than hits.

Bo luc lac ($36), known informally as shaking beef, was underseasoned and clumsily assembled on the plate. An appetizer of coconut-encrusted shrimp ($16) seemed overpriced for a plate of four individual pieces. The vegetarian summer rolls ($11) were packed with julienned raw vegetables and, strangely, served sliced in rounds, a curious presentation that enabled all of the filling to spill out once picked up.

Most of the items on the appetizer platter ($32 for two people) were underwhelming: tacky spring rolls, bone-dry fried pork ribs, tough shrimp skewers and bland papaya salad. A plate of white prawn-topped garlic noodles ($30) was mostly bean sprouts, with very little garlic to speak of. The menu says that the noodles were wok-tossed, but the absence of any sear or wok hei led me to believe that the wok itself must not have been very hot.

The cocktails didn’t fare much better. The Guava Pisco Sour ($15) and jalapeño-flavored Spice of Saigon ($14) were poured tiki bar-strong and were so sour as to be almost undrinkable. I suppose I would have liked to be a little tipsier for this experience, but my drink was so unpalatable that I couldn’t even finish it.

The lone exception to the menu’s overall lack of seasoning was an impressive chicken salad ($15), a crunchy mixture of peanuts, shredded green cabbage, delicate and aromatic banana blossom and raw vegetables liberally dressed with nuoc cham. The kitchen didn’t go easy on the fish sauce or lemony rau ram (that’s cilantro’s spicy cousin), making the salad wonderfully pungent. Each bite screamed of flavor. If I had only eaten that and the smooth black sesame creme brulee ($11), I would have been much happier.

Nostalgia is a blurry lens through which we can view history. We often rewrite it so that the hard, inconvenient parts are pushed to the sidelines in favor of what makes us feel good.

Indeed, the space at Le Colonial is beautiful and pleasing to look at. It references the film set of “Indochine” — sumptuous and historically accurate — but not its actual plot, which follows the parallel dissolutions of French colonial rule over Vietnam and the unraveling life of its heroine, a French woman who owns a rubber plantation. (In real life, that rubber would likely transform into Michelin tires and transport gourmets to centers of haute cuisine throughout Europe.)

The restaurant is frozen at the exposition phase of the narrative, focused on a smoothly run colonial environment that is precarious in the same way a house of cards might look on the eve of a hurricane.

Why is it so easy to block out the whole picture? “Part of the confusion comes about from the fact that these narratives are very powerful,” Nguyen said. “It’s easy to get seduced by high-quality productions and to enjoy them.” Even when such depictions belittle you, it can feel like a perverse compliment when you’re not used to being seen by mainstream culture at all. “At least I’m there on the screen,” Nguyen said. “I’m a part of the show.”

It might be helpful to think of this dilemma in terms of food historian Michael Twitty’s cooking workshops in the American South. Visitors to the plantations don’t get a “Gone With the Wind”-style take on history that celebrates the lavish whitewashed buildings. Instead, Twitty’s work demands that visitors look the specter of chattel slavery in the eye. Peters explained: “He likes to distinguish between reenactment, which is about wishing you could recapture plantation society and enjoy the beautiful times, versus what he’s doing, which is not reenactment but education.”

As we walked out of Formosa Cafe, Nguyen noticed a line of framed, black-and-white headshots near one of the restaurant’s bars. They depicted actors Anna May Wong, Keye Luke, Wilbur Tai Sing and others.

“This is amazing,” Nguyen said, pointing up at the photos. “I don’t think this was here before.” A placard nearby noted that the portraits were part of a curated exhibit by filmmaker Arthur Dong, titled “Hollywood Chinese at the Formosa.” The exhibit recognizes the wealth of Asian American talent that has entertained audiences on film, television, stage and radio.

Until then, I had written off the Formosa Cafe as another glorified tiki bar. My eyes caught the glances of the portraits, all people who made their bread acting as dragon ladies and inscrutable Chinamen in the movies. Here, on the walls of this bar, they all shined together. Maybe that’s one solution to the empathy dilemma at Le Colonial — what would be a similarly smart way to honor its community?

The difficulty I have with Le Colonial is that its nostalgia is completely unrelatable. There’s nothing poignant about it; I don’t want to go back to that time and place, to presume that I would be the person served and not the one doing the serving. It makes sense that Le Colonial opened as an expression of a particular cultural longing in the 1990s, and it’s not my intention to demand that restaurants that outlive their political correctness be automatically thrown into a wood chipper. All I ask is that we, diners and restaurateurs alike, try harder to not let beauty deceive us into believing untruths.

Soleil Ho is The San Francisco Chronicle’s restaurant critic. Email: soleil.ho@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @hooleil