Andy Kerstetter of Idaho Mountain Express discusses The Sympathizer and Viet Thanh Nguyen’s experiences as a young refugee.

No matter what he did, Viet Thanh Nguyen has always felt a pervasive sense of haunting—not so much like he was plagued by actual ghosts, but rather the specter of the past, particularly the Vietnam War and the fact that he and his family were Vietnamese refugees in a land he felt didn’t want them.

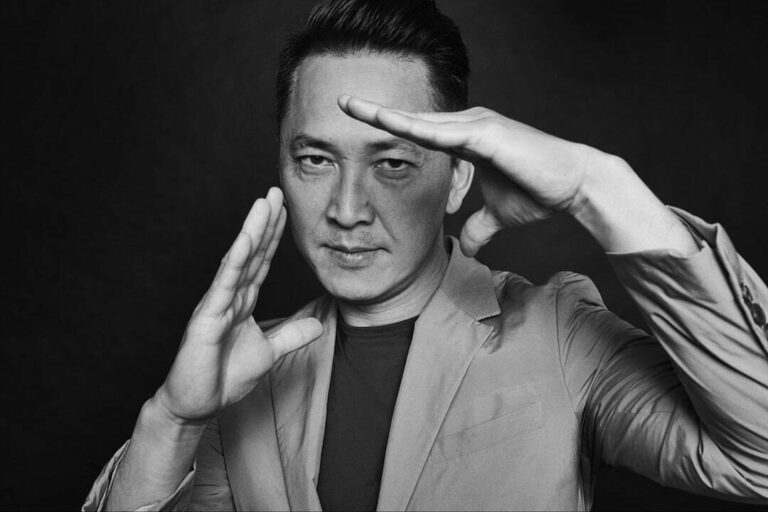

“I sometimes felt like we were the ghosts, haunting the American landscape,” Nguyen said in a talk at the Church of the Big Wood in Ketchum on Thursday, March 8.

Nguyen and his family fled Vietnam to the U.S. in 1975, when he was 4. In 2016, he published his first novel, “The Sympathizer,” which won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction.

Growing up in America, Nguyen noticed that most movies and books about the war focused on Americans, while the Vietnamese were erased. He was inspired by this lack of representation to write about the war from a Vietnamese perspective.

The novel’s Vietnamese protagonist throughout the story goes from a double agent for the North Vietnamese army in South Vietnam to refugee and even cultural advisor on a suspiciously “Apocalypse Now”-esque film about the Vietnam War.

Nguyen said the fictional film being produced in the book is an amalgamation of all the American war movies about the Vietnam War, and in the book, the protagonist’s suggestions to include more lines of dialogue in Vietnamese by actual Vietnamese people are shot down.

And in real life, when people hear his story, Nguyen said they often ask him if he’s seen “Apocalypse Now,” which he said is symptomatic of the problem.

“For Americans, the Vietnam War has to remain an American war,” Nguyen said. “Americans can’t imagine living in a country that produces refugees.”

And that is one of the reasons he thinks so many critics and readers have dubbed “The Sympathizer” an “immigrant novel.”

“It’s an American reflex to call it that—it affirms our mythology of ourselves,” Nguyen said. “This is not an immigrant novel—it’s a war novel and a refugee novel. … I say this is a war novel and a refugee novel because these two things are, to me, indistinguishable.”

He said one of his goals for the book is to make people think about what makes people become refugees—that war affects all people, not just soldiers.

“I knew I was entering a complicated place in American consciousness,” he said.

At the same time, being hailed for the book sometimes makes Nguyen uncomfortable.

In a review of the novel, The New York Times wrote that it “fills a void … giving voice to the previously voiceless while it compels the rest of us to look at the events of 40 years ago in a new light.”

But that’s a distinction that Nguyen takes issue with.

“Have you met any Vietnamese people? We are a very loud people,” he said.

He said that claiming one person as the voice of the voiceless “allows us to ignore the cacophony of voices from any given community. … That’s why I say I don’t speak for anybody.”

Still, Nguyen—who now chairs the English department at the University of Southern California, where he is also an associate professor of English and of American studies and ethnicity—felt compelled to write the novel to highlight the issues surrounding the Vietnam War.

He discussed how, at 4, he was separated from his parents and brother when they were assigned to a “relocation camp” in Pennsylvania, and how, after moving to San Jose, Calif., and opening a Vietnamese grocery store, his parents found a racist, anti-immigrant sign on the business door.

“I grew up watching my parents struggle in that store, but I knew the person who wrote that sign didn’t know that,” Nguyen said.

He said the sign anonymously placed on his parents’ business was a sign of an old American story—that Americans had always been afraid of immigrants.

“We were just the newest feared generation of immigrants,” Nguyen said. “I felt it becoming more necessary to become a writer to change those stories.”

He joked that his struggles growing up in America gave him the requisite emotional damage to become a writer.

“I spent most of my life trying not to think about that,” he said. “But when you become a writer, you have to go back to the places where it hurts.”

But in the end, one thing he realized was that he and other refugees could not and should not forget their past, something his protagonist stated near the end of “The Sympathizer,” when he said, “The point was simply this: the most important thing we could never forget was that we could never forget.”

Nguyen’s talk was put on by The Community Library in partnership with the Sun Valley Center for the Arts as part of The Center’s BIG IDEA project, “This Land Is Whose Land?”