Jaehun Lee of BC’s student newspaper The Heights reflects on Viet Thanh Nguyen’s appearance at the college as part of the Lowell Humanities Series.

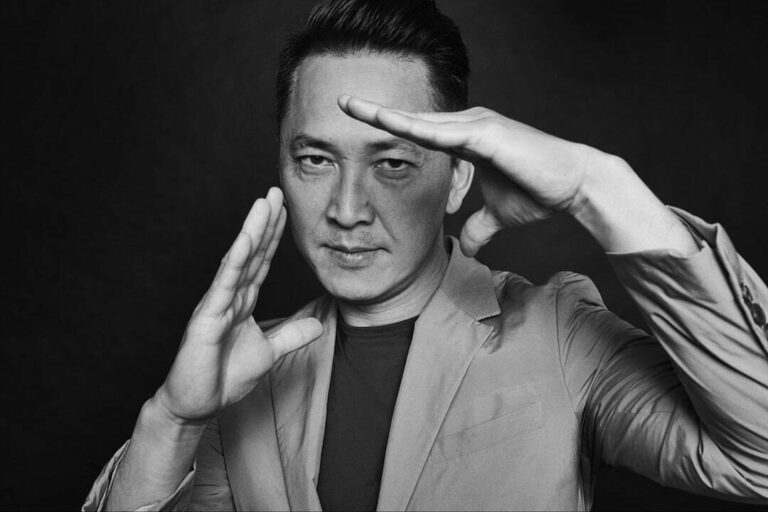

Viet Thanh Nguyen, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and Aerol Arnold Chair of English and professor of American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, spoke on Wednesday evening as part of the Lowell Humanities Series. He has written numerous critically acclaimed books, including The Sympathizer, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, and The Refugees.

Nguyen’s talk focused on how his identity as a refugee appears in and drives his writing. From the beginning of his talk, he emphasized the importance of not forgetting one’s past and identity prematurely, an especially pertinent question in the modern times.

“One may argue that because of the person that I’ve become, and the way that I look, and the profession that I occupy, I shouldn’t call myself a refugee anymore,” Nguyen said. “But it seems to me that there’s a necessity for [continuing to be called a refugee] because the impetus for erasing the refugee histories.”

He posited that the fear surrounding refugees stems from their seeming inability to fit in the American Dream. Immigrants come to America on their own free will to achieve it, he argued, whereas refugees did not. He noted that while the United States calls Asians the “model minority,” it also initially did not want them.

“If you knew anything about Vietnamese refugees in the 1970s and 80s, you would know that we were really good at cheating welfare and getting in insurance fraud,” Nguyen said. “But we’ve forgotten that in 1975, when the United States took in 135,000 Vietnamese refugees, the majority of Americans did not want [them]… Why can’t Syrians become model minorities?”

While he was hailed as a voice for the voiceless by critics following his debut novel The Sympathizer, he did not see it as a compliment, claiming that it exhibited the work we had remaining to listen to refugees’ histories and to truly understand them. He argued that people prefer to have him be the voice for the voiceless because it does all the listening work for them. In a sense, his latest book of short stories, The Refugees, attempts to solve this issue by offering a diverse, truthful collection of voices.

“I was worried about being called the ‘voice for the voiceless,’ so I wanted as many voices as possible,” Nguyen recalled. “The Refugees is about the diversity of Vietnamese people… and… the people they’ve encountered.”

Nguyen criticized a one-lane, streamlined perspective set by the dominant American culture of driving this disregard for the narratives and stories of refugees, which Nguyen fights in his work. He was also sure to remind the audience that refugees remain affected even after the event that forced them to flee.

“The war is actually not over for so many people,” Nguyen said. “People remain traumatized. People remain shaped… all wars are fought twice: first… on the battlefield, and a second time in memory.”

Moving on from such histories too soon had negative effects for the United States—notably exhibited in Charlottesville, Va. in August—but also for refugees who have stopped calling themselves such, as they tend to forget their roots and turn their backs on newer refugees. He firmly believes that literature cannot solve this problem on its own: Action also had to follow literature. As a parent, he makes sure his son is aware of his Vietnamese heritage and his father’s refugee past.

“We don’t have to completely shield [children] from the difficulties of the world,” Nguyen said. “It’s important to remind them of what they have, what they don’t have, and the histories.”

Nevertheless, he acknowledged the power of literature to help us remember histories before they are forgotten. When the City of San Jose wanted to build a new city hall, it forced Nguyen’s parents to sell their grocery store. When Nguyen returned to the area to receive commendation from the city, he noticed that there was no acknowledgement of his parents’ store having ever existed—a parking lot now stands in its place.

Nguyen points to experiences such as these as the impetus for his novels, arguing that if we truly remembered the refugees’ stories and listened to their voices, we would not be so quick to judge or dismiss them.

“That is why I’m a writer,” he said. “Because if I didn’t write and there were other people who didn’t write, these stories would be gone… forgotten. This erasure would never be known… The point was simply this: The most important thing we could never forget was that we could never forget.”