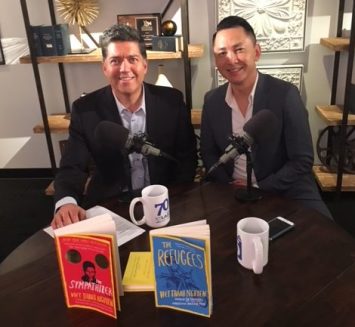

Frank Buckley interviews Viet Thanh Nguyen for KTLA. The interview video can be seen on the KTLA website.

Viet Thanh Nguyen is the author of “The Sympathizer,” a spy novel set in the chaos of 1975 Saigon for which Nguyen won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Viet was born in Ban Me Thuot, Vietnam, and fled as a four-year-old with his family in 1975 to the U.S. as Vietnam was enveloped in the chaos of the end of the war.

Viet and his family were initially transported to a refugee camp in Pennsylvania but eventually moved to San Jose, California where his parents opened one of the first Vietnamese stores in the city. Viet attended U.C. Berkeley and earned a Ph.D. in English. Today, he is University Professor of English, American Studies and Ethnicity and Comparative Literature and the Aerol Arnold Chair of English Studies at the USC Dornsife School. He is the author of several books including “The Refugees,” “The Displaced,” and “Nothing Ever Dies” among others.

During this podcast, Viet discusses his family’s refugee story and the plight of refugees everywhere. He also reveals the challenges he faces as a writer and explains why it took more than 15 years to write the short stories collection “The Refugees.”

Frank Buckley: Welcome to Frank Buckley Interviews. Tonight, our guest is the winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for the book The Sympathizer. It’s author, Viet Thanh Nguyen.

Announcer: Frank Buckley Interviews starts now.

Frank Buckley: He writes about Vietnam and the refugee experience from a very personal point of view. Viet Thanh Nguyen escaped Vietnam in 1975, amidst the chaos of the end of the war.

Viet Nguyen: My dad was in Saigon. My mom had to make a life-and-death decision about what to do, so she took my brother and me, and we walked downhill about 187 kilometers to the nearest port town, through a landscape of war and devastation. My brother remembers dead paratroopers hanging from the trees. I feel lucky that I don’t remember those kinds of things. Grabbed a boat, went to Saigon, found my father, and a month later had to do it all over again once the communists reached Saigon as well.

Frank Buckley: The amazing journey and the American success story of Viet Thanh Nguyen when we come back.

Viet, welcome to the program.

Viet Nguyen: Thanks for having me, Frank.

Frank Buckley: You bet. It’s interesting we’re having this conversation. Twenty-one years ago this summer, you arrived in LA as a young assistant professor at USC, just having achieved your PhD at Berkeley. And you, instead of plunging right into your work at University, you sit down at your kitchen table in an apartment in Silver Lake, and you start to write the book that I’m holding in my hand now: The Refugees, a series of short stories. I’d like to start there and ask you as you were sitting down in that kitchen to write these stories, what were you trying to say about the refugee experience? And has that experience changed in the 21 years since you sat down to write this book?

Viet Nguyen: Well, you know, I grew up as a refugee in a Vietnamese refugee community in San Jose, California, and I knew that I was surrounded by stories. These people had lost everything: their country, their relatives, their identities, their careers, and so on. And yet they were living in a country in which when people said Vietnam, people really meant the Vietnam War, and when they said the Vietnam War, they meant the American War. And so I knew that all these stories that Vietnamese people had undergone were not known outside of the Vietnamese community, and that was the ambition that I had in sitting down to write The Refugees.

And I think that while the situation for Vietnamese Americans who are refugees has changed pretty drastically, the situation for refugees around the world hasn’t. So I wanted to try to make a connection between what had happened to Vietnamese people and to refugee conditions in general.

Frank Buckley: So that people know more about your personal journey, you were four years old, I believe, when the fall of Saigon was happening, and you had to suddenly … with your brother, seven years older than you, and your mother … get out of town. And your father was out of town on business, and you had to leave so quickly you didn’t even know his fate, and he didn’t know your fate. Tell us about your journey.

Viet Nguyen: Yeah, well we were living in a small town called Boun Me Thuot in the Central Highlands, which is famous for coffee and for being the first town overrun in the final invasion of 1975, so yes, we were cut off. My dad was in Saigon. My mom had to make a life-and-death decision about what to do, so she took my brother and me, and we walked downhill, about 187 kilometers to the nearest port town, through a landscape of war and devastation. My brother remembers dead paratroopers hanging from the trees. I feel lucky that I don’t remember those kinds of things. Grabbed a boat, went to Saigon, found my father, and a month later had to do it all over again once the communists reached Saigon as well. And that was the beginning of our journey to the United States.

Frank Buckley: You leave Vietnam at the age of four, I believe, and you end up in Pennsylvania eventually, your entire family together. But then they pull you apart, and even though you were young and you don’t remember much, you do remember that moment where you were taken from your parents’ arms. Can you tell us about that, and why did they do that?

Viet Nguyen: Well, we ended up in a refugee camp, and there were 130,000 other Vietnamese refugees. And we were all put into one of four refugee camps, and ours was in Pennsylvania. So in order to leave, you had to have a sponsor, an American sponsor, take charge of you. And in our case, I don’t know what happened, but no one would take the entire family of four, so my parents went to one sponsor, my 10-year-old brother went to a second sponsor, and I went to a third. And that’s really where my memories begin, being taken away from my parents. And now I’m the father of a four year old, so I can see very vividly what I might have looked like at that age, and of course I would be heartbroken to have my son taken away from me, and the same in his case.

So that’s what happened, and it was done with the best of intentions, obviously, because the sponsor program was meant to help Vietnamese people adapt to American society, but for a four year old, there’s no comprehension of that. There’s only this sense that you’re being taken away from your parents, and so my earliest memories are about screaming and howling as I was being taken away, so … and that memory has never left me.

Frank Buckley: I was gonna say, how did that affect you? How … yes, the memory is there, but how did it affect you?

Viet Nguyen: I think personally it was the beginning of a long chain of events that are not unusual for refugees and immigrants, which is that my parents had to work 12-hour, 14-hour days every day of the year except Christmas, Easter, and New Year’s in order to support the family and to raise us and give us everything that they thought we needed, right? But in order for them to do that, that meant that they were never at home spending time with us.

And so being taken away from my parents was just the beginning of this long process of sort of emotional damage that comes along with being a refugee or an immigrant child. And I think in order to cope with that, I suppressed many of those feelings for a very, very long time. But in order to become a writer, the problem is that you have to uncover those emotions. You have to go where it hurts, which is why, I think, it took me 17 years to write The Refugees, for example. It’s important for me never to forget what that feels like, because now, of course, we’re living through another refugee crisis, and a lot of people have problems feeling empathy for refugees. They wanna close the borders, for example, and I have to remember how I felt in order to continue feeling empathy for these new refugees, and speaking out for them and what they’re going through.

Frank Buckley: And you sort of write about the craziness of that period in The Sympathizer, and you talked about the first line of the book and working so hard to find that first line of the book. And if I can ask you to indulge me, I’m gonna ask you, if you wouldn’t mind, to read the first few lines of The Sympathizer, and then describe for me the process to get there and why you wrote it that way.

Viet Nguyen: Sure.

“I’m a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I’m also a man of two minds. I am not some misunderstood mutant from a comic book or horror movie, although some have treated me as such. I’m simply able to see any issue from both sides.”

So I wanted to write a novel that evoked that history that you’re talking about: the fall of Saigon and the Vietnam War, and to tell it from a perspective that we hadn’t seen before, because there was obviously thousands of books, hundreds of movies made about this war. And so I created a character who was half Vietnamese, half French, and a spy caught between all sides, and his one talent is that he can see any issue from both sides, which many people are not capable of doing. And the point of the book, partly, is that inability to see issues from both sides is what drives us to war. And my narrator’s tragic condition is that he’s able to see both sides, but no one really cares about that, and seeing things from both sides makes you very, very vulnerable.

Frank Buckley: When you finally wrote the last words and submitted it to your publisher, did you know this is something special? Did you feel good about it?

Viet Nguyen: I felt great about it. I felt great about it. But let me put that in a little bit of context. I felt great finishing the novel, and my agent said, “We have something special here. I just don’t know if it’s gonna sell, but we have something special here.” And then we submitted it to publishers to try to sell the book, and 13 out of 14 rejected the book. So that was a very, very long day for me because the 14th editor didn’t buy the book until the very end of the day, so I was about ready to give up hope. So I felt great about it, but obviously I felt a lot worse about it during those eight or 10 hours we were waiting for responses.

Frank Buckley: How does that happen? The book that is … I don’t know how many languages it’s been translated into now, it’s all over the world, it’s the winner of the Pulitzer, it’s one of the best pieces of fiction in recent times, and 13 out of the 14 publishers that you submit to say, “No, thank you.”

Viet Nguyen: I don’t think it’s actually a unique story. If you look at the history of rejections, many books have undergone this. I think Marlin James, who won the Booker Prize, his first book was rejected by 70 or 80 publishers. So that puts it into context it wasn’t that bad for me, and we still sold it on the first round and on the first day. But I think that, number one, the publishing industry, like many industries, is scared of taking risks. So this book looks a lot different than a lot of other so-called Vietnam War novels, and I deliberately wrote the book so that it would be different, that it would be provocative, that it would take risks. And of course, when you do that you have to be ready to deal with rejection and incomprehension as well.

Frank Buckley: And you’re right about the fact that we have to see Vietnam and the people of Vietnam in a very different way because of your novel. Until then, we see them as these one-dimensional characters in movies like Platoon, or Apocalypse Now, and I think Apocalypse Now in particular was one that sort of … is annoyed the right word, or sort of ate at you?

Viet Nguyen: Provoked me.

Frank Buckley: Provoked you.

Viet Nguyen: So what’s interesting is that your generation, my generation knows these kinds of movies like Platoon and Apocalypse Now, and that’s true all over the world, because wherever I would go talking about the Vietnam War, people would know about Apocalypse Now, right? But I don’t think we can even take that for granted anymore, because I think the younger generation has not seen this movie. So for me though, that was a defining moment, to watch Apocalypse Now when I was 11 or 12 years old, much too young of an age, and to see that Vietnamese people in the American imagination really only exist as props for the American imagination. And of course, that’s not my experience of Vietnamese people. They have … they’re flesh and blood. They have histories, they have stories, and that’s all erased in movies like Apocalypse Now.

And so The Sympathizer is about telling our own stories, but also, I have to admit, taking revenge on Apocalypse Now and on Hollywood for the ways that they have erased Vietnamese people.

Frank Buckley: Yeah. There’s a scene in The Refugees that really sort of stuck with me, and I wrote this down, and I’ll read it and then ask for your reaction as to why you wrote this. And it’s where the narrator is sitting with her mother watching Korean soap operas, and she said, “I had stayed to watch one of the soap operas she rented by the armful: serials of beautiful Korean people snared in romantic tangles. ‘If we hadn’t had a war,’ she said that night, her wistfulness drawing me closer, ‘we’d be like the Koreans now. Saigon would be Seoul. Your father, alive. You, married with children. Me, a retired housewife, not a manicurist.’ Her hair was in curlers, and a bowl of watermelon seeds was in her lap. I’d spend my days visiting friends and being visited, and when I died 100 people would come to my funeral.”

It took me, reading that, right to the pain of that family. And I wondered is that how Vietnamese people, not just you, but … and this reader … but is that how Vietnamese people feel about what has happened to their country in terms of what could have been?

Viet Nguyen: I think everybody who’s lived though some kind of traumatic history feels that way, and I think a lot of people, for example, feel survivor’s guilt. Like why did we get out of the country, for example, and not everybody else? And when I go back to visit Vietnam, people there ask exactly the same question: why were you so lucky to get out of here? So they think about alternative histories as well. And then everybody who’s been through a traumatic history, I think, thinks about parallel histories. What if history had taken a swerve and gone another direction, as the mother here is talking about? And so we’re always thinking about what could have been. And that’s true for even the Koreans. When I go to Vietnam, a lot of Koreans are there now as business people and students, for example, and they go to Vietnam and they think wow, Vietnam is where Korea was 30 or 40 years ago. They also think about alternative histories.

And so all of us who are caught up in this history see the different possibilities of where our lives could’ve been if something different had happened, and they think about what would happen if we had stayed behind in that country as well.

Frank Buckley: And I wondered about that as well, that in a sense the people who were able to get out of Vietnam as Saigon was falling must have felt blessed. We’re getting out before the true danger arrives, but on the other hand you’re then escaping to something that is completely unknown and is not going to be embracing. You talk about the fact that, while today we look at Vietnamese and say, “Oh, the model minority. Look how successful they are.” I think you sited a poll that said 30%, or less than 40%, of the Americans wanted the Vietnamese refugees to arrive, so you get on the boat, you get on the plane, you arrive in America, the promised land, and you’re rejected.

Viet Nguyen: Mm-hmm (affirmative). You know, most Vietnamese people probably didn’t even know about the polls that said 36% of Americans didn’t want them here. I think they were feeling what you described, which is relief and blessings on the one hand about getting out and saving their lives and their families’ lives, but also tremendous fear. I mean, imagine if you or me, for example, at our age suddenly had to give up everything, flee the country, and embark on a completely new life for which we’re not prepared.

Frank Buckley: With our children.

Viet Nguyen: With our children.

Frank Buckley: Yeah.

Viet Nguyen: And my parents were younger than me when that happened to them. It’s immensely terrifying, which is why I think that underneath the surface of Vietnamese-American success … and there are a lot of success stories … underneath that surface, especially for the generation of my parents, is also a lot of pain of what they lost and what they underwent and the traumas of being a refugee, or an immigrant, here in this country, the rejection that they might have felt from other Americans, but also the fact that they could see their own children transforming and becoming Americans and speaking English instead of Vietnamese. And I think all these things added up to a very hard life for many of these first-generation refugees.

Frank Buckley: And you talked about a sort of a survivor’s guilt too, because when people left they couldn’t bring their extended families. They grabbed who they could and left.

Viet Nguyen: Yeah.

Frank Buckley: And so now you’ve left behind uncles and aunties and other family members, and now many years after the war, has there been a reconciliation? Have those families reconnected? Has it been awkward?

Viet Nguyen: It’s always awkward. When we fled, my mother left behind our adopted sister, her adopted daughter. And she did it because she thought we would be coming back one day, which was a logical belief at the time. And of course we didn’t come back, and my parents wouldn’t see her for 20 years. I wouldn’t see her for over 30 years. And I grew up aware that we were missing somebody, because my parents had one black-and-white wallet-sized photograph of her at 16 years old, and I grew up wondering who is this person? Why is she not here? And so there was always this absent presence, this little haunting in our family for me. And that was true for just about everybody in the Vietnamese refugee community. And so we grew up, all of us, or we lived with that sense of loss and of people missing. And my mother, for example, had to deal with the death of her own parents when she was gone, when she couldn’t come back. It’s tremendously painful for so many people.

And so those emotional residues are there so that when we go back to Vietnam we carry that burden with us, but then the Vietnamese people who stayed behind have their own burdens, because Vietnam was a devastated country for decades after the end of the war. And the Vietnamese people there genuinely feel that they were the unlucky ones and we were the lucky ones to get out. And it leads to so much difficulty, as you say, and makes reconciliation challenging, if not difficult. And so that’s why I think overseas Vietnamese people, when they go back to Vietnam, feel quite a bit of trepidation. They fear the communists. They worry about their own families, what they’re gonna think. They come back loaded with gifts and money, ’cause that’s what you’re supposed to do, but also to assuage, maybe, some of the guilt as well.

Frank Buckley: It took you so long to finish The Refugees. It took you 20-

Viet Nguyen: 17 years.

Frank Buckley: 17 years. And in the meantime, I think you wrote three non-fiction books, you wrote The Sympathizer, you were extremely productive as a writer and as an academic, and I wonder was it difficult for you each time to sit down to go back to this? And now that it’s done, and now that it’s out there and we’re all reading it, how satisfying is that?

Viet Nguyen: It’s extremely satisfying. So let me just say that people can probably read this book in about three or four hours, like the audio book that I recorded I think is four hours long, but it took me 17 years as you said. And it was an absolutely miserable experience almost every step of the way, which is not what the reader is going to experience, and for good reason. I’m not atypical. Many writers spend enormous amounts of time in order to craft stories that readers can read very, very quickly and feel very quickly.

So it was an enormous relief just to finish that book and get it out of the way, because the experience was so difficult. The opening story, for example, “Black-Eyed Women,” took 50 drafts over 17 years, and it was such a relief to be done with it, because it almost broke me as a writer to go through that experience. But I think it was absolutely necessary.

This is what makes someone into a writer: the willingness to confront this kind of a process. Writing The Sympathizer doesn’t make someone into a writer. It took me two years to write that book. It was a joy to write, and I could do that only after the suffering of 17 years for The Refugees.

Frank Buckley: But why was it so painful to write that story over and over again, and how did you know when the 50th draft was the right draft?

Viet Nguyen: I think that the … I started writing short stories because I didn’t know how to write, and I thought short stories must be easy to write because they’re short, and unfortunately the reality is the shorter you go, the harder things get. Took me a long time to figure that out. Took me 17 years to realize that with writing short stories less is more. And my instinct as a writer though is that more is more. The Sympathizer is an example of that. It’s a novel that has a lot of things happening in it, and that’s my natural form. So with writing The Refugees it was really about trying to go against my own grain and trying to write things that were very, very compressed, and trying to tell human stories, an entire life really, in the space of 15 or 20 pages, and picking just the one incident that lets us see that life unfold. And that was a very particular kind of challenge that I was not very talented about.

Frank Buckley: But was the pain in reliving some of those moments, or sort of picking at that part of you that you had talked about suppressing, or was it just the physical pain of sitting in that apartment in Silver Lake and wherever you moved to after that and banging out the words?

Viet Nguyen: It was definitely both. I mean, writing is partly about that physical and mental process of learning the craft and sitting in a room for 10,000 hours in California when there’s many better things to be done outside, and then partly it’s about learning how to feel your own emotions, because even if I’ve not literally been in the shoes of most of the characters in that book, I have to try to feel what they feel. And that’s what writers have to do. So there’s a story there, for example, about an elderly woman taking care of her husband who’s losing his mind to Alzheimer’s. I have not been there in that situation, but I have to try to think about what he feels, what she feels, and we all feel that. We’ve all felt the pain of losing somebody. We’ve all felt the fear of losing our own memory, and that’s what a writer has to do is to imagine, and it takes a lot of work to get to that point.

Frank Buckley: Finally, I just wanna ask how your family feels about your success? Your brother, Tung, went to Harvard.

Viet Nguyen: He went to Harvard, and then just to rub it in he went to Stanford as well. Yeah.

Frank Buckley: You write multiple books, you become a university professor at USC in the Dornsife School, you have a Pulitzer Prize, amongst a trunk full of other awards. Are your parents still living?

Viet Nguyen: They’re still alive, yeah.

Frank Buckley: And how do they feel about all this?

Viet Nguyen: Well, I think they feel … they do feel proud. I think for most of my life they just felt … they probably felt a state of incomprehension. Like, you’re an English major? What does that mean? You’re gonna get a doctorate in English? What does that mean? They were just happy I got a job at USC, so I was gainfully employed. But I never told them that I was gonna become a writer. I think that would’ve just been going too far. So when the books come out, then I bring them home, and I show my parents, and they’re proud of the books, and they take photographs with them.

But I think the reality of it all was brought home when I won the Pulitzer Prize, which I won when I was on the road, on a book tour. And I didn’t even think about calling my parents to let them know about this prize, because I think part of me felt well, that’s just bragging. And so my dad called me two days later, and I was still on the road, and my dad is a very stoic man, not emotional. This time he calls me, his voice is shaking with happiness as he says, “The relatives in Vietnam called. You won the Pulitzer Prize.” And so I think that has been important to them, this recognition that the books have been recognized, through the Pulitzer Prize, in a way that’s meaningful even to Vietnamese people. And I feel that if that makes my parents proud, then I’m happy, that all it took was a Pulitzer Prize to bring us together.

Frank Buckley: Well, Viet, this has been a pleasure. Thank you so much.

Viet Nguyen: Thanks so much, Frank.

Frank Buckley: Thanks again to Viet for a terrific conversation. If you’d like to hear the entire uncut version of our conversation, check out the Frank Buckley Interviews podcast. It’s available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Thanks for your feedback on social media. If you’d like to join the conversation, I’m frankbuckleytv on Twitter and Instagram, and there’s a Frank Buckley Facebook page as well. I read every single one of your comments.

Thanks for joining us. We’ll see you next time.