Lou Berney of CrimeReads includes Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer on the list of classic chase novels that “master survival and suspense.”

Every few months or so—and this has been happening for as long as I can remember—I dream the same dream: I’m running, I’m hiding. If I get caught, I’m dead.

The details change. Sometimes I’m in my own neighborhood, sometimes I’m on another planet or a hundred years in the past. Sometimes I don’t know who or what is hunting me, sometimes I do.

Always I feel trapped, terrified, and willing to do whatever it takes to get away, to disappear.

So it probably makes sense that I’m fascinated by stories about characters on the run. When I decided to take my own crack at it, with November Road, I turned for inspiration to a few of my favorite novels. Here are the things that I learned (i.e., stole) from each of them.

Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley

(What Have I Done?—aka The Inciting Incident)

Frankenstein isn’t just one of the most beautiful, harrowing, and wonderfully disturbing works in the English language: it’s a great chase novel. The very first time we glimpse Victor Frankenstein’s creation, in fact, he’s fleeing across the ice in a dog sled, drawing Victor, in pursuit, deeper and deeper into the frozen nowhere.

For me as a writer the most important structural element of a plot is the inciting incident, the big bang that yanks the main character out of his or her everyday life and kicks off the dramatic conflict. A good inciting incident often leaves the main character wondering, Oh, shit, what have I done?

(In the 1977 thriller Sorcerer, for example, Roy Scheider’s character realizes that his gang has accidentally robbed a bingo game with connections to a powerful, vengeful mob boss.)

When Victor Frankenstein watches the “dull yellow eye” of his creation flicker open, Mary Shelley gives us one of the best Oh, shit, what have I done? inciting incidents ever.

No Country For Old Men, by Cormac McCarthy

(The Dreadful Predator)

In a novel about characters on the run, the antagonist often assumes an outsized importance. If the predator doesn’t create dread, if the prey’s escape seems a foregone conclusion or even a decent possibility, the dramatic conflict falls apart.

For me there’s no predator who creates more dread—no one I’d least want to meet in my nightmares—than Anton Chigurh in No Country For Old Men.

What makes Chigurh so memorably scary? Part of it, I think, is what he represents. He’s not just a very bad dude, the way McCarthy shapes him, but also an implacable force of nature, ill-willed fate itself, metaphysical doom.

Plus, he is a very bad dude. A very competent bad dude, which is maybe his most frightening quality. One of my favorite beats is when Chigurh shoots the unnamed big-wig in his high-rise office. Chigurh uses a shotgun shell loaded with shot “the size collectors use to take bird specimens” because he doesn’t want to shatter the window and raise suspicion.

The Talented Mr. Ripley, by Patricia Highsmith

(A Very Resourceful Fugitive)

But a successful dramatic conflict is all about the balance between desire and obstacle. A protagonist on the run can and should be outmatched and overwhelmed, which is why his or her resourcefulness—think David v. Goliath—is critical.

A good main character doesn’t have to be likable, just compelling. Odysseus, on the run from Poseidon, is kind of an asshole. But he’s tricky as hell and that (a) makes him fun to watch; and (b) gives him a fighting chance at surviving the Anton Chigurh of Greek gods.

Tom Ripley in Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley is a more-than-worthy successor to Odysseus. Sure, if you want to split hairs, Tom is a cold-blooded murderous identity-stealing sociopath. He’s also gloriously, fascinatingly tricky. From the very first sentence of the novel, Tom’s mind is working, the wheels turning. “Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way.”

At the end of the novel he may not escape emotionally, but he does manage to elude both the Italian police and an American private detective. I believe it. And, despite myself, I applaud him.

The Passenger, by Lisa Lutz

(Remember: Life on the run is hard)

This terrific contemporary thriller has a simple premise: a woman’s husband dies and she goes on the run. Well, all right, it’s not the simple. The woman didn’t kill her husband, but has lots—and lots—of secrets. She has to go on the run.

One of the things that makes The Passenger so good—in addition to Lutz’s prose, her feel for character, the twisting plot—is the attention to detail, the authenticity, the grit and the grind. The main character, Tanya, doesn’t have any special skills or connections or resources that will make her escape easier.

In this novel, there’s nothing glamorous about life on the run. Tanya, flees to Nebraska and then to Austin and Wyoming and upstate New York. She’s not, in other words, sipping cocktails and watching the sunset in Venice. She’s dyeing her hair in motel bathrooms and laboring with a razor blade over a fake passport that she hopes will pass muster at a Western Union office.

This, you think as you read The Passenger—the tedium and the dread—is what trying to disappear would really, truly feel like.

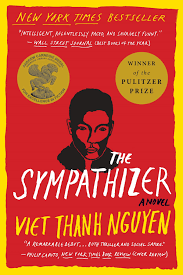

The Sympathizer, by Viet Thanh Nguyen

(There are many different kinds of fugitives.)

A book as rich, complex, and crazy smart as The Sympathizer, which won both the Edgar Award and the Pulitzer Prize, defies categorization. And it doesn’t really fit any rigid definition of a chase or fugitive novel.

But the unnamed narrator and main character, a Communist double-agent who escapes Vietnam at the end of the American war and takes up residence in California, is most definitely on the run. Not only is he forced to flee his homeland on one of the last planes out of Saigon, he’s also trying to escape his past, the burden of history, his various identities, his own divided heart and mind.

And life for him in the United States, as a conflicted deep-cover mole, is perilous in every possible way. Viet Thanh Nguyen made me realize that the distinction between refugee and fugitive is maybe less sharp than I assumed it to be.

In case any of that seems pretentious and puts you off this novel, let me assure you that The Sympathizer is also hilarious, thrilling, and hugely entertaining. I think that’s what drew back again and again to this novel—how well (like all great crime novels) it works both on the surface and down in the murky, fascinating depths.

Bonus Novels

I can’t let you go without mentioning five more fantastic “on the run” novels that either influenced me greatly when I was writing November Road or—in the case of a couple of them, which I read after I turned in the manuscript—were so good they made me feel bitter and insecure:

- The Thirty-Nine Steps, by John Buchan. A classic for a reason.

- Killshot, by Elmore Leonard. Marriage is even more complicated when you’re on the run together.

- Dear Daughter, by Elizabeth Little. Great voice, great main character, a novel truly of the now.

- The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead. An epic American poem.

- Sunburn, by Laura Lippman. Brilliant re-imagining of classic noir.