A collection of short stories delicately captures the traumas and triumphs of the migrant experience. The following review by Fatima Bhutto originally appeared in the Financial Times.

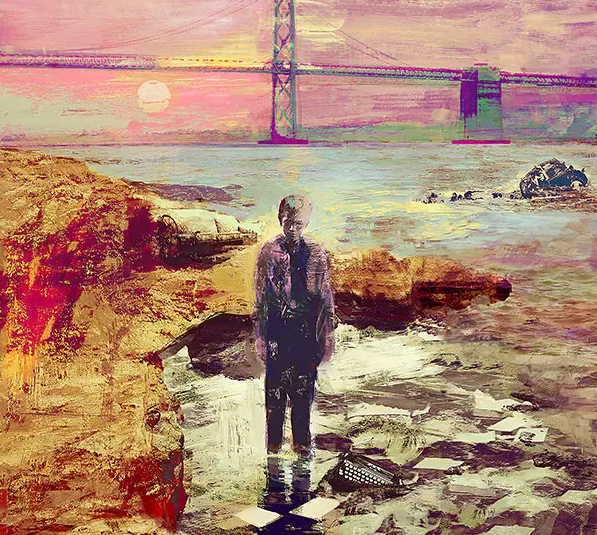

Who are we when we lose our footing? When — by the stroke of circumstance and politics — we belong nowhere and everywhere at once? Viet Thanh Nguyen’s poignant collection of short stories, The Refugees, follows the call of those and many other restless questions. Nguyen, himself a refugee from Vietnam who won the Pulitzer for his 2015 debut novel The Sympathizer, returns with a softer and more elegant form, each of his eight stories suffused with hauntings. There are those haunted by the sea — all of the refugees’ voyages in this collection begin, or end for some, with water crossings — while others remain haunted by what it means to straddle borders, not just of physical displacement but the uncertain, dangerous terrain between life and death, secrets and clarity, remembering and forgetting.

Nguyen writes most movingly of the debt of safety and freedom and how it impoverishes the lucky survivors; men and women who, having survived war and displacement, find themselves living in relative comfort, terrorised by an unanswerable question: why me?

“Black-Eyed Women”, which opens the collection, follows a ghost writer haunted by the actual ghost of the brother who gave his life for hers. He appears at night and sits on her sofa, his skin smelling of brine and his eyes unblinking. “Why did I live and you die?” his sister asks him. “You died too,” the ghost replies, “you just don’t know it.”

The Refugees, given its subject matter and the enormity of contemporary travel bans, racism and conflict, has a light but powerful touch. In “I’d Love You to Want Me”, Mrs Khanh, whose husband has taken to calling her by another woman’s name as he slips into dementia, is displaced from home in multiple ways. It’s hard enough to accommodate the strangeness of life in California, even all these decades later, and to accept the Americana that seeps into her Vietnamese family — a son who calls her from Las Vegas after eloping, screaming about love on the telephone — but now her husband and her children are strangers to her, and she must admit, with some unhappiness, that “as much as she loved her son, she liked him very little”.

Nguyen is delicate in describing this rupture caused by one generation of refugees living in an imagined, anxious past while their children are born with the privilege of blank slates, imagining no past at all, but futures that will allow them — require them, even — to build any kind of life they wish.

Nguyen is delicate in describing this rupture caused by one generation of refugees living in an imagined, anxious past while their children are born with the privilege of blank slates, imagining no past at all, but futures that will allow them — require them, even — to build any kind of life they wish.

Vivien, a young woman who returns to Ho Chi Minh City (which Nguyen is pointed in calling Saigon) to visit the father her mother abandoned to seek a better life in America, is typical of this disconnect between the past and the present. Vivien, impossibly glamorous and liberated to her Vietnamese half-siblings, has built an entire self on the lies that all dislocated people tell themselves: that they are who they claim to be, that things will one day be better, that in time, all the haunting of their displacement — the ghosts of loss, hunger and poverty — will pass into oblivion. The characters all possess a trail of this hope, a yearning to both belong and to forget.

Nguyen’s stories are to be admired for their ability to encompass not only the trauma of forced migration but also the grand themes of identity, the complications of love and sexuality, and the general awkwardness of being. For all their serious qualities, they are also humorous and smart. Liem, a refugee who arrives in San Francisco to be housed by a young gay couple in “The Other Man”, treads gently into his new city having only been warned that “in San Francisco the people tended to be unique, an implication he hadn’t understood at the time”. Nguyen places his reader in sympathetic solidarity with Liem as he grapples with idiomatic expressions such as “you’re killing me” and the distinction between the colours mauve and purple.

The form of the short story seems to come to Nguyen effortlessly. His novel, The Sympathizer, seemed at moments burdened by the writer’s attempts to show how much he could do, how far he could go. The language — to this reviewer, at least — landed heavily and didactically (I have never heard a living soul use “crapulent” in actual conversation). Every story in The Refugees, however, feels as though one is witnessing a performer unaware of being watched. There is no contortion, no sleight of hand, and Nguyen’s prose is better for it.

Nguyen writes of ancestral homes and new refuges and the scattered space of land and sea between them with a unique poetry. “In a country where possessions counted for everything,” he writes of America, “we had no belonging except our stories.”

Fatima Bhutto is author of ‘The Shadow of the Crescent Moon’ (Penguin)