Walter Ryce of Monterey County Weekly interviews Viet Thanh Nguyen ahead of CSU Monterey Bay’s 21st annual Social Justice Colloquium.

CSU Monterey Bay’s 21st annual Social Justice Colloquium is titled “The Ethics of Remembering and Forgetting: On Memory, Wars, and Resistance.” Angie Tran, CSUMB professor of political economy, calls it “a forum that brings together the CSUMB campus community and the broader communities to raise consciousness about the inhumanities of past and current wars in which the U.S. has intervened.”

The Vietnam War figures prominently in the two public events. It begins on Tuesday, April 4, with a screening of students’ short films in Fort Ord: Veteran Stories (noon-2pm, Cinematic Arts Studio), followed by Meghan O’Hara and Mike Attie’s documentary In Country, about combat veterans re-enacting the Vietnam War (2-4pm). Then the proceedings move down the street for an audio installation of stories from the Veteran’s History Project (4:30-6pm, VPA Complex, Building 17), which segues into a reception 5-6pm with Vietnam and Cambodia scholar and artist Binh Danh.

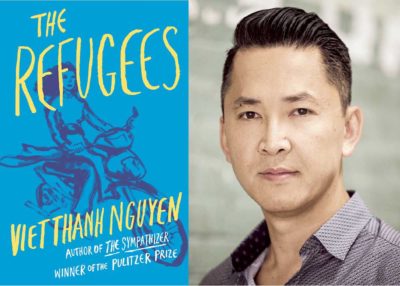

Then from 6-8pm on Thursday, April 6, a star keynote speaker in Viet Thanh Nguyen. His family came to the U.S. as refugees in 1975, settled in San Jose, and opened a neighborhood grocery store. He went on to become professor of American and ethnic studies and chair of English at USC. His first novel, The Sympathizer – a response to Apocalypse Now – won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

His follow-up nonfiction book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War, is a finalist for the National Book Award and National Book Critics Circle Award. His latest, The Refugees, is a collection of short stories that The Guardian calls “superb” and “exquisite.“ Currently on a book tour, Nguyen was recently on Late Night with Seth Meyers looking dapper and having a swell time. He should. He’s crushing it.

Weekly: Does a writer, like your protagonist in The Sympathizer, inhabit multiple viewpoints at once?

Nguyen: I think a good writer has to be able to do that. Because one of our basic tools as a writer is empathy – the capacity to feel for others and to put ourselves in the place of others. Without that, we can’t imagine characters and worlds that are different from our own.

How have you cultivated that trait?

Growing up in California, I felt I was living in two worlds. When I was in my parents’ household or the Vietnamese community, I felt like an American outsider observing them. When I was in the rest of American society, I felt like a Vietnamese person watching Americans. I felt like I was a spy. That sense of duality is something I have cultivated to be a better writer and scholar.

Was there a point when you felt like you were officially American?

I think when I won the Pulitzer Prize. [Laughs.] I’m sort of half joking but not joking. Winning the Pulitzer feels to me like I accomplished something that can’t be taken away from me – ever. But even that is potentially troubled. There are some Americans out there who continue to regard me as not American. I get hate mail in that regard.

How are immigrants different from refugees?

Immigrants are more acceptable than refugees because they come with the intention of settling, and they have chosen the country they are arriving in. Often if they are legal or documented, they’re also welcome in the countries they come to. Refugees are the unwanted.

Why don’t refugees appeal to this so-called Christian nation’s sense of good samaritanism?

Racism and xenophobia. That’s the basic answer. We have in the U.S. a tradition of pluralism, inclusion, diversity. We [also] have a tradition of racism and xenophobia. That goes back to the very origins of the country and it’s not an accident or aberration. It is fundamentally part of the American identity. Many Americans don’t want to acknowledge that. And there is no easy solution to it. We’re a country based on a contradiction. Which does not make us unique.

Do you feel like you are charged with interpreting Vietnam and Vietnamese people for Americans?

I think any Vietnamese-American writer who writes is charged with that task because of the very unequal way that storytelling happens in this country, which is if you’re part of a majority you’re not expected to translate or represent anything. But if you’re part of any minority, you are. I do take it upon myself to speak about Vietnamese issues and the Vietnam War because I know that winning the Pulitzer has given me more visibility. [But] Vietnamese people, like any other population, like Americans, are not homogeneous and you can’t say they really believe in any one thing.

What’s been your favorite question on this book tour?

Honestly, it concerns my sartorial sense – my clothing, my fashion, my hair. The rest of it is all this stuff about my life and my writing and my politics and so on. I have answered many of these questions dozens of times over. But talking about my appearance is much more fun.