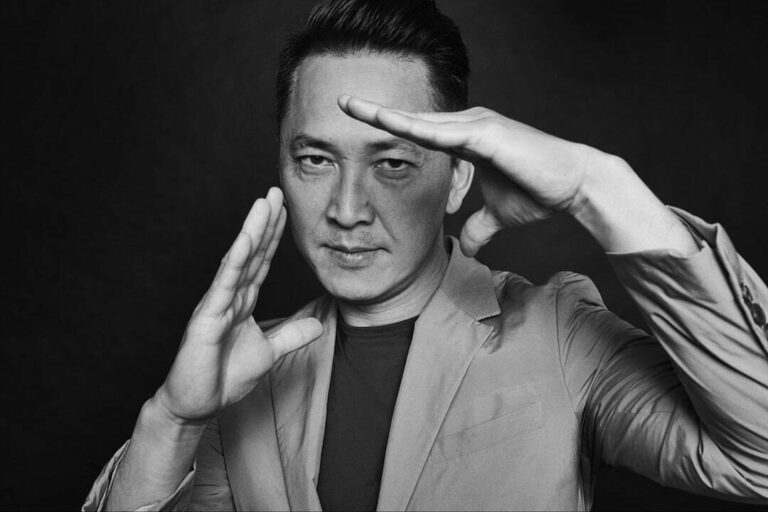

Viet Thanh Nguyen won the 2016 Dayton Literary Peace Prize in fiction for his novel, The Sympathizer. The Dayton Literary Peace Prize is first and only annual U.S. literary award recognizing the power of the written word to promote peace. The awards will be presented at a gala ceremony hosted by award-winning journalist Nick Clooney in Dayton on Nov. 20. This article was originally published on daytonliterarypeaceprize.org.

The philosophy of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” informs the composition of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s profoundly instructive novel, which refuses to operate as purely literary or historical fiction, but it must turn into a spy thriller, a political satire, a black comedy of ideas on history, war, race. Jailed by those he has served as a communist sleeper agent in America, the narrator confesses “in a style of his own choosing” what transpired over the course of the fall of Saigon and his relocation to America. This nameless everyman, half-French and half-Vietnamese, whose secret mission to learn “American ways of thinking” first led him to Emerson, employs Emersonian tricks and confesses in an aphoristic, contradictory, capacious fashion, exhaustively cataloguing Vietnamese experience after decades of war and foreign manipulation: “(T)he parade of paupers” outside the Saigon cafes along with “military amputees … elderly beggars … street urchins … young widows and cripples”; the desperate radio chatter as Saigon collapses; the humbling jobs that befall those Vietnamese who reach America and the violent deaths some meet while in exile. There is no safe haven. Nothing is ever purely what it seems, and “the best kind of truth mean(s) at least two things.”

Absurdities abound and never more so than when the narrator serves as a technical consultant to the movie about the Vietnam War. Made in the Philippines with Asian everymen– Vietnamese extras are only employed for background chatter and acting dead. What they say is unimportant but it must sound real. “Dead Vietnamese, take your places!” And so they do: They rise again in this furiously composed novel and demand we reconsider Vietnam and its people “skunked by history.” This necessary fiction, this Emerson-infused enthusiastic work has Whitman’s breadth. The great poet’s wide embrace of all things American is doubled in this powerful American Vietnam War novel with its wide embrace of all things Vietnamese.

— Christine Schutt, 2016 finalist judge

On winning this prize, Viet Thanh Nguyen writes:

“As a realist, I don’t believe in peace. As an idealist, I have to believe in it. We live in bloody and fearful times, but I think back to how, only a few millenia before, our human imagination was once limited to our tribe. Realism meant seeing the world only as far as the horizon. Now we can see further, and our imagination extends far beyond the horizon. Perhaps writers have something to do with that expansion of the imagination, which has occurred while we as a species have collectively groped towards the end of war, conflict, violence, and abuse. The role of writers in these half-blind efforts is twofold. We can portray the worst of what human beings do to each other, and in so doing we can remind readers, and ourselves, that inhumanity is a part of humanity. In the face of that cruel truth, we can also imagine the best that humanity is capable of, and in that way provide a vision, a way to overcome the momentum of past conflicts and inherited bitterness, the inertia of accepting our brutality. A strong dose of unsentimental realism, mixed with a touch of wild idealism—that is one way to imagine what I attempted to do through The Sympathizer. I am honored by this prize, which recognizes that in writing about war, I was also hoping for peace.”