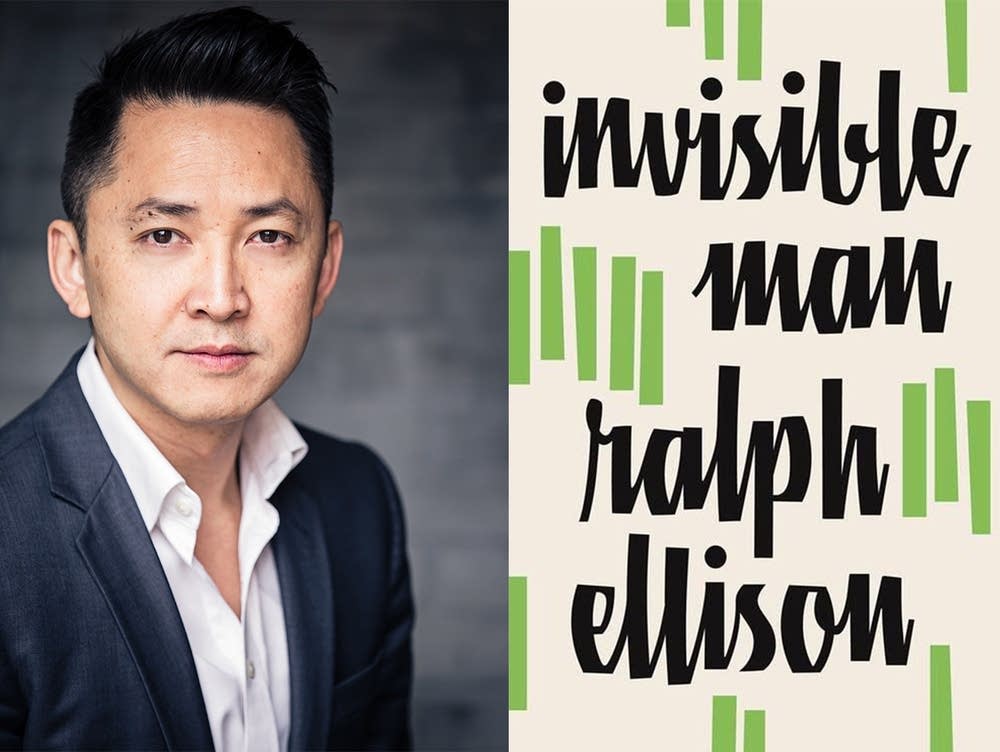

Viet Thanh Nguyen discusses reading ‘Invisible Man’ on The Thread with Kerri Miller. Listen to the full podcast on MPR News or read the transcript below.

On The Thread podcast, books are just the beginning. Host Kerri Miller talks with comedians, scientists and other big thinkers about how books and reading have shaped their lives.

Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen knows what it’s like to be invisible in a crowded room. His family came to America as refugees from Vietnam and his work — including his novel “The Sympathizer” — explores the way immigrants are often ignored in this county in daily life, only to find themselves subjected to intense scrutiny in moments of crisis.

He spoke with Kerri Miller about Ralph Ellison’s novel, “Invisible Man,” a book he said inspired him to become the writer he is today.

Here is the transcript:

Viet Nguyen: I see myself as a writer who’s writing his books alone in his room, but who also imagines himself in collaboration, in solidarity with many other political and social movements outside of literature.

Keri Miller: I’m Keri Miller and this is the thread podcast where books are just the beginning. Here’s what happens. Ask a scientist, a comedian, a radio person for a book that gets stuck in their head, and you’ll learn as much about them as you will about the book.

Viet Nguyen: Has Kanye West read Invisible man? I don’t know, but Kanye West operates in a universe, and Beyonce too, where the efforts of Richard Wright, of Ralph Ellison, of Zora Neale Hurston have laid the groundwork eventually for the possibilities of some of the things that they’re doing.

Speaker 3: (singing)

Viet Nguyen: Okay? That’s the optimistic, hope. Right, that once you introduce an idea and you release it into the wild of American culture, that it can have unexpected consequences. Now someone has to sit there and actually trace that genealogy out, but I’m convinced that you couldn’t have some of the things that hip hop, rap music, Beyonce are talking about without whole genealogy of African American political and cultural struggle of which invisible man is a part.

Keri Miller: Novelist and professor Viet-An Nguyen was reading about that struggle long before he could understand it. Even his book pick, Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, wouldn’t truly resonate with him on his first read. As a skinny little kid set loose in the library, Viet excelled at finding books he wasn’t supposed to be reading.

Viet Nguyen: For me it was rebellion. It was also my home away from home literally. In my particular case, my parents were working all the time. We were refugees. We were just trying to survive. They were just trying to survive, which meant that they were doing everything for my brother and myself. But ironically, that meant that they went around emotionally to take us out to places or anything like that or spend time with us. So I turned to the library for that. So it’s both, you know, gave me a sense of a safe space, but a safe space that was also a dangerous space because of everything that was unleashed. Another book that I remember reading at much too young of an age, Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth.

Keri Miller: Oh my gosh. That is hilarious. How old were you?

Viet Nguyen: I don’t know, childhood is this big blur, but definitely before I was physically ready to make sense out of it. So reading it, I don’t remember anything about the novel like after the first 50 pages. But I distinctly remember reading the first 50 pages where all the good stuff happens, like our narrator, Portnoy masturbating with his family’s slab of liver and then putting it back in the freezer and then having to eat it later with his family. And that stayed with me until the right moment when I was writing my own novel. And just by coincidence, I was one day writing the book, and then I stopped and I had to prepare dinner.

Viet Nguyen: And it was squid. I had never cooked squid before. And so I started cleaning the squid, which involves, putting my fingers into it. And I thought, wait a minute, this is interesting, reminds me of something. And of course it made its way into the novel.

Keri Miller: Oh my gosh. That is hilarious.

Viet Nguyen: And of course it made its way into the novel because Portnoys’ Complaint was hiding back there somewhere.

Keri Miller: Viet’s novel, The sympathizer, written by a writer whose first name carries the legacy of his country, asks what it means to be Asian and invisible in contemporary America.

Viet Nguyen: For myself and for so many people who aren’t black, the idea of invisibility as a racial minority holds true. So for Asian Americans like myself, Vietnamese Americans, we’re not invisible in the same way that black people or black men are invisible. But we have some degree of that. So I could understand what it meant to be invisible to most Americans at most points in my life. And yet, to be hyper visible at moments of crisis. And that’s what invisible man is partially about. It’s about what it means to be a black man who no one sees, except when they see him as a threat. And that’s enormously threatening and damaging. I mean it’s enormously threatening cyclically, but also physically for black men and for black people.

Viet Nguyen: And for Asian Americans, for Vietnamese Americans, it’s the same experience in some ways that we’re invisible until we’re perceived as a threat, and then we become hyper visible and all these horrible racial stereotypes become attached to us. And in regards to the Vietnam War, that’s completely the case. Now, with the case in terms of reading Larry Heinemann’s Close Quarters, that for American soldiers like the ones he was depicting, of course Vietnamese people were invisible to them.

Viet Nguyen: They were unimportant until they went to Vietnam and they were threatened by them. And then Vietnamese people became either sexually threatening or physically threatening because there were the Viet Cong and they had to be put down. So how could I write a novel that would respond to that crisis from the perspective of the invisible person? And so I … The opening of my novel, the first paragraph, if you’ve read the first pages of invisible man, you can hear the echoes of that book in my own.

Viet Nguyen: “I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces. Perhaps not surprisingly, I am also a man of two minds. I am not so misunderstood mutant from a comic book or a horror movie, although some have treated me as such.”

Viet Nguyen: And so the plight that my character deals with is a version of the Invisible Man’s plight, except in my case, I turn it into a question of being a man of two minds and two faces. And that’s because he’s a spy, so that’s literally his situation. But it’s also a rendition of the Asian version of the Invisible Man crisis, which is that if you’re an Asian American or if you’re an Asian in the west, you have often placed upon you that old idea, that Richard Kipling put forth, that east is east and West is west and never the twain shall meet. And the Western perception of Asians in the West or of Asian Americans or of Asian Europeans, is that they are perpetual foreigners, that they’re always going to be divided between east and west. And that’s a canard. It’s not true. But that’s the imposition that’s put upon us. And that’s the dilemma that I wanted to make as a central crisis in my novel.

Keri Miller: Wow. So much to follow up on what you’ve just said. When you’re saying about the visibility and the invisibility of black Americans, of course that’s so relevant to today with what’s happening with black lives matter. But the other thing I was thinking about is when you talk about how powerfully stories transmit history and culture and contemporary history as well, I thought, yes, if we’re all reading those stories, right? If it isn’t the kind of, to use the word, segregation of literature in the way that we segregate, not so much physically anymore, but culturally. Do you know what I’m saying?

Viet Nguyen: Yeah, absolutely.

Keri Miller: Who’s reading the Invisible Man today and taking the very contemporary lesson from that, that fits what’s happening around us today?

Viet Nguyen: I see myself living in a universe of stories, literary stories, but also other kinds of stories, cinematic stories. Movies for example, so I teach my students what I call Hollywood cinema industrial complex when it comes to the Vietnam war? And I say, “Yes, each of these movies are just stories, but collectively they tell a very powerful story that persuades and seduces all of us into remembering history, remembering the American culture in a certain way.”

Viet Nguyen: Now, it’s true. Literary novels like Invisible Man or even let’s say Beloved, in the contemporary period, they may be read by a lot of people, but by a lot of people were probably talking tens of thousands of readers. Right? And that’s a very small population compared to the millions watching Hollywood movies. But if we think about this as an ecosystem or a universe of stories, the stories that are being transmitted in literary fiction have a wider impact over time, I think, especially if these books become embedded in a Canon.

Viet Nguyen: Because if we think about how, in the 1960s, black literature for example, was not a part of the American literary Canon. You would not be taught these books in college or high school. And now 50 years later, you cannot teach an American literature course in an American University today and not teach black literature. You’d just be considered retro grade, borderline racist. So there has been a transformative impact in the collective efforts of writers and critics, book reviewers and so on in the literary world, that has had a ripple effect across the idea of what American literature means.

Viet Nguyen: And the average American college student, whether or not they’re going to go onto a career of reading Morrison and all that, they know that nevertheless, their education has now been shaped permanently by the collective force of, in this case, African American storytelling. And so I think that’s the larger vision that I have for how these literary works eventually do have wider significance in the culture.

Keri Miller: I hear that. I also know you’re speaking of that as an academic. And I wonder how many people would understand how incredibly relevant what Ralph Ellison is saying.

Viet Nguyen: Well, you know, I think that, for example, in Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, obviously the literary world knows who he is. Most other people outside do not.

Keri Miller: Right.

Viet Nguyen: Actually, when I mentioned Invisible Man to my non literary friends like, “Hmm? Who is this?”

Keri Miller: Science fiction?

Viet Nguyen: Yeah. And you’re right. Maybe as an academic, I have a self fulfilling hope that you could write a book that many people would not read, but that the idea itself, the ideas themselves in the book, might circulate because of the ripple effect.

Keri Miller: This is something that a Junot Diaz was a part of that literary serious Talking Volumes that I was telling you about. And he says it is essential that we read authors from many different backgrounds, very, very many different life experiences. And yet, I see how mainstream publishing, I don’t wanna spend too much time on what’s going on in New York, but there is a real emphasis in mainstream publishing on a few of the writers that kind of fit that Junot Diaz description, and then a big bunch of pretty similar back rounded life experienced writers that end up on the bestseller list and end up being taught in a lot of universities. I don’t know if we’ve made as much progress on that as you would want to think.

Viet Nguyen: There’s two responses to this question. One is obviously when you’re within any kind of a world, in this case, the literary world, you inflate your own self importance. So you think, “Oh my gosh, Junot Diaz, a great writer. Everybody must know him. His one book or two books can change everything we think.”

Keri Miller: That’s also the easy way out too. Right?

Viet Nguyen: And that’s the easy way out because it’s simply not true. And I don’t think he’s going to make that claim. I think that to go back to the whole example about Kanye West, Beyonce, African-american literary and political struggle, cultural struggles. Literature itself is a part of change, but it cannot change the world by itself. Now, in the literary world, you forget that these writers would not have emerged, Diaz or any of these black writers or Asian American writers, would not have emerged except also for the fact that there’s all these other movements for change that are happening outside of literature.

Keri Miller: That’s a good point.

Viet Nguyen: Right?

Keri Miller: Right.

Viet Nguyen: I see myself as a writer who’s writing his books alone in his room, but who also imagines himself in collaboration, in solidarity, with many other political and social movements outside of literature, that the world of literature can expand our intellectual horizons, expand our sense of what is possible, can deal with serious moral and political conflicts, and that this can be working in conjunction with the fact that there’s people working with Black Lives Matter. There’s people engaging in anti war protests.

Viet Nguyen: There’s people struggling for Bernie Sanders or socialism or whatever. All of this is happening. They need to be understood as happening together. Right? That’s how New York is … This is why New York is publishing Junot Diaz. It’s not simply because Junot Diaz emerged out of nowhere.

Keri Miller: That’s a really good point.

Viet Nguyen: It’s because the 1960s happened. It’s because radical protests happened in the streets. And the rest of the country had to respond to that in various kinds of ways, including the literary world. So this is the danger that a literary world that’s hermetically sealed believes that it can simply train writers and that they’re just so talented that they’ll change the world. It’s simply not true. We read Jhumpa Lahiri today, not because Jhumpa Lahiri is so great, but because there’s been a whole history of Asian Americans struggling to find their voice, literally protesting in the streets, getting arrested, getting sent to jail, struggling to change immigration opportunities.

Viet Nguyen: They’ve created a whole climate for someone called Jhumpa Lahiri to come out and for everyone to Christian her as a genius. But it wouldn’t have happened without decades and decades of political struggle that go back to the 19th century. That’s the hidden history behind the emergence of gigantic literary figures. The other thing I want to say about Junot Diaz, it’s not a knock on Junot Diaz or Jhumpa Lahiri. They accrue all these awards. They’re at the forefront of the literary world. And like you’re saying, there’s all these other writers who people have not heard of who may be working in a related world.

Viet Nguyen: The reality of it is that we don’t know, 50 years, 100 years from now, who’s going to be remembered. We can look back on American literary history in the past hundred years and look at the history of the Pulitzer prizes, and half those people we have not heard of. We have forgotten.

Keri Miller: Geez, is that right?

Viet Nguyen: Well, a good portion of them. Or they’re not as important as other writers who were not getting these kinds of prizes at the time. So take everything with a grain of salt in terms of who was being lionized, including myself. I’m not saying I’m lionized, but my book has gotten a certain amount of recognition, but who knows if it’s going to be read or how it’s going to be read in 50 or 100 years. And so, there’s numerous kinds of figures from 100 years ago or 50 years ago we could look at and think the reputations have declined. For example, John Dos Passos. I was just talking about him … to somebody about him last night. Huge figure of the 1930s and the 1940s. Completely, almost utterly unread today.

Keri Miller: Viet couldn’t have known, of course, that when we recorded the interview, he was soon going to join the ranks of major award winners. On April 18th, The Sympathizer was awarded the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. Will that change how people read his work or will it impact his legacy? Well maybe, but Viet told me as soon as the book was published, he started hearing from people who said his writing had opened their eyes in new ways to the people they saw every day.

Viet Nguyen: When my novel came out, there were people who were writing to me saying, “I never knew these kinds of things were happening to Vietnamese people and to Vietnamese refugees.” And these were being written by other Americans or by people who were living in Southern California who lived in cities like Westminster nearby here, where there are thousands of Vietnamese refugees, and yet they knew nothing about the lives of these people. And that just brought home to me that what I thought of as very intimate and as everyday knowledge about what was happening to Vietnamese people, Vietnamese Americans, Vietnamese refugees, again, was completely unknown by other Americans and it reinforced a sense for me that it was so crucial to tell these stories so that at least 50,000 people, whoever is reading this book, wouldn’t know these stories. That’s 50,000 more people than before, who had never heard these stories.

Keri Miller: Right, right. I’ve heard these stories. How do you think it is that you live side by side. I mean it is kind of what I was getting at before with do enough … Yes. The culture might be influenced by the Invisible Man, but if you haven’t read it and you don’t have an awareness of it, is it really making a difference? And so then I ask how is it the people in a community like this can live side by side and have that little … not blaming anybody for that, but just how is it? … have that little of awareness of those kinds of stories.

Viet Nguyen: I think a lack of empathy, a lack of imagination. And it’s very common.

Keri Miller: On the part of the …

Viet Nguyen: On all our parts. We’re always encountering people who we don’t think twice about either whether it’s this other individuals who are actually like us for example. But also, if you live in California, you’re constantly in the presence of people from different cultures, different histories, different world.

Keri Miller: That’s the great thing about the state.

Viet Nguyen: Right. But if you don’t think about it, the only way that you’re encountering them is you go to their restaurant or they’re the person who comes in and cleans out your garbage can. And you don’t think that these people have these tremendous histories behind them. And I’m speaking of someone who knows that all of these Vietnamese refugees who are living here in the United States, who are doing stuff like doing your nails for $10, those people had to go through enormously difficult experiences to get there, experiences that most Americans have no understanding of and will never have to suffer.

Keri Miller: Or maybe interest, right?

Viet Nguyen: Or interest in. They’re just the people who are kneeling at your feet doing your pedicures. So my awareness of those experiences makes me aware that the person from El Salvador who is cleaning my office, most likely has a tremendous history behind her that brought her here. And Americans tend to think, when they think of heroes, they think, “Oh, the astronauts are heroes. They went to the moon or into outer space.” Frankly, most refugees who come to this country, the odds of their surviving that trip and making it here are much worse than what astronauts face. And that’s something that Americans simply don’t comprehend. And it’s the power of stories to try to make those histories visible to other people. Right? And so hopefully, Hollywood will make those movies, probably not. But then it’s left up to writers to do that kind of work.

Speaker 3: (singing)

Keri Miller: Novelist Viet-An Nguyen, his book is Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man. Next time on the thread …

Speaker 4: I think that was like a huge step in that way of saying instead of always covering it up and all there pretending like, “Oh my divorce. It was okay. I’m so much better off now. What do you mean? This was the right thing for me.” I am a mess and I was a mess for a really long time and this was really hard, I think is, you know, sometimes really freeing

Keri Miller: Leah Tau on dropping her guard.

Speaker 3: (singing)

Keri Miller: The Thread is produced at MPR news by Maddy Mahan with help from Stephanie Curtis. Search MPR news and The Thread. And you’ll know why we say books are just the beginning. I’m Keri Miller.