Viet Thanh Nguyen reviews Hua Hsu’s A Floating Chinaman: Fantasy and Failure Across the Pacific. Originally posted as a New York Times Book Review on July 24, 2016.

A FLOATING CHINAMAN

Fantasy and Failure Across the Pacific

By Hua Hsu

276 pp. Harvard University Press. $29.95.

For critics and scholars, the greatest rewards are to be gained in bestowing attention on authors whose stock is already high. Why, then, should a writer look toward one of the forgotten? And how to select someone to elevate? This is the task that Hua Hsu, an associate professor of English at Vassar, sets for himself in his smart new book, “A Floating Chinaman: Fantasy and Failure Across the Pacific.” His chosen subject is the mostly unknown H. T. Tsiang (18991971), a Chinese immigrant who “created some of the most ambitious and, at times, bizarrely self-aware works of modern American literature.

As Hsu makes painfully, comically evident, Tsiang was condemned mostly to self-publication. This “sad sack” peddled his books from a suitcase and wrote furiously to anyone who would help his literary cause. Decades after his death, his work at last found an audience through the edgy Kaya Press, which recently released his 1935 novel “The Hanging on Union Square” and is bringing out his 1937 novel “And China Has Hands.” But during his lifetime Tsiang suffered the incompatible indignities of being spied on by the F.B.I. while being rejected or dismissed by progressive writers like Theodore Dreiser. And in a situation verging on slapstick, a desperate Tsiang finally found his work recommended to an important publisher, Richard Walsh, who happened to be married to Pearl Buck. Unfortunately, in Tsiang’s novel “China Red,” he had “likened Buck’s work as America’s favorite China expert to prostitution,” and had also attacked Buck’s husband. Walsh rejected Tsiang’s books.

Hsu uses Tsiang’s misadventures to illustrate the “trans-Pacific imagination” that has united, and divided, China and the United States. On the American side, one way of understanding China was as a nation of “400 million customers,” as the journalist Carl Crow put it in a 1937 book of that title. This rather shallow perception persists today, with the number growing to over a billion customers. Perhaps if he had been a more talented novelist, Tsiang could have breached the great wall of ethnocentrism and racism from whose parapets Crow could also write books titled “The Chinese Are Like That” and “I Speak for the Chinese.” More likely, the only way Tsiang could have been heard would have been to transform himself into an accommodating interpreter of Chinese culture, like the popular Lin Yutang. Instead, Tsiang’s leftist political beliefs contributed to his confinement to Ellis Island and near deportation.

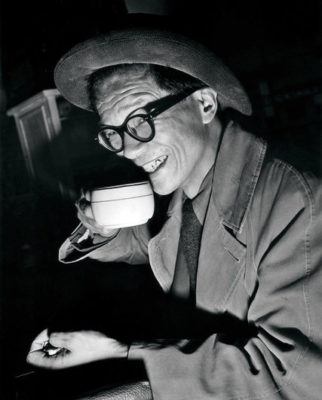

Tsiang was indeed the “floating Chinaman” of Hsu’s evocative title — a title, Hsu tells us, borrowed from an unpublished and perhaps unwritten Tsiang novel. Written or not, that novel could have had no more fitting conclusion than what actually happened to Tsiang. In his life’s final strange chapter, of which I wanted to hear much more, he eventually becomes a “very minor Hollywood celebrity” acting in movies like “The Keys of the Kingdom” and television shows like “I Spy,” where he often played the stereotypical Chinaman. Failure? Maybe. But whose failure? Hsu points the finger and jabs it to make sure no one misunderstands: Tsiang’s tragedy was to be a nativeborn China expert residing in a country where Americans considered the tens of thousands of Chinese living among them to be no more than laundrymen.

Viet Thanh Nguyen’s debut novel, “The Sympathizer,” won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize for fiction. He is also the author of “Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War” and the co-editor of “Transpacific Studies: Framing an Emerging Field.”

A version of this review appears in print on July 24, 2016, on page BR16 of the Sunday Book Review with the headline: A Great Wall.