University professor and author Viet Thanh Nguyen shares his personal story of challenges and success. This interview was originally published by Maureen LittleJohn for Culture Magazin.

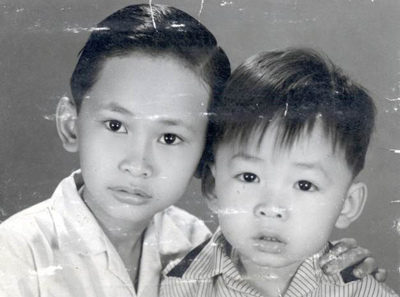

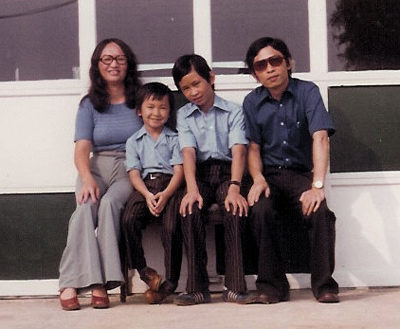

Viet Thanh Nguyen came to the the United States with his family in 1975. He was four and his brother was ten. His parents opened a grocery store, their business flourished and Viet and his brother went on to become successful university professors. It sounds like the American Dream. However, things were not all that they seemed on the surface.

In this interview with Culture Magazin, Viet reveals what it was like to be Vietnamese growing up in California in the 1970s. He also explains his motivation to write his latest novel, The Sympathizer (Grove Press, 2015), about a conflicted spy during the Vietnam War.

You are a university professor and author, most recently, of The Sympathizer. Did you always have dreams of teaching and writing? Can you describe the journey to your current success?

I wrote my first book—a small one—in the third grade. By the time I got to college, it was my fantasy to be a writer, and I wrote on and off through my college years. When I graduated, I knew I wasn’t good enough to stake my future on being a fiction writer, so I went to graduate school to get my doctorate in literature instead. I had some talent for academic research and writing, but I had no idea of what it meant to be a teacher. I began learning that skill in graduate school, and found I had some ability there, too. This was how I became a professor. Although I enjoyed the work of teaching and research, I promised myself that when I earned tenure, I would return to writing fiction with greater dedication. In my thirties, that is what happened. I spent my thirties doing research for a book on the Vietnam War and memory, and writing a short story collection. The experience of writing that collection was mostly miserable, but it taught me how to be a writer. By that I mean I learned both the technical skills and, just as importantly, the resolve necessary to confront the loneliness of writing fiction. The collection remains unpublished, but what it taught me enabled me to write my novel in two years.

You were born in Vietnam but left on a boat at age 4. Was that in 1975? Can you tell us how that felt?

Yes, it was April 1975, although that was our second time fleeing. Our first time was in March 1975. My family lived in Ban Me Thuot, a small town that was the first one overrun in the communist invasion. My mother was there with my brother, my adopted sister, and me, while my father was in Saigon on business. With the lines of communication cut off, she decided to leave with my brother and me and tasked my sister with staying behind to guard the family property. My mother believed that the war was not over and that we would return. That didn’t happen and I would not see my sister again for nearly thirty years. My mother, my brother, and I walked downhill a few hundred kilometers to Nha Trang. Apparently it was horrible, with many refugees and dead soldiers. My brother wrote about it in a story. We caught a boat to Saigon, where we found my father. I don’t remember any of this. My narrative memory begins in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where we were resettled. All Vietnamese refugees had to have sponsors to leave the refugee camp, but in our case, no family could take all of us. My parents went to one sponsor, my ten-year old brother to another, and myself to a third. I was four. Although my separation from my parents was only a few months, it felt like a very long time. The trauma of separation initiated me into memory and left its imprint on me. This is one way the war fundamentally shaped a child.

What was it like to grow up in San Jose, California?

We moved there in the late 1970s because economic opportunities were limited in Harrisburg. When I returned to Harrisburg several years ago, I realized that the last neighborhood we lived in was a ghetto, which was not how I remembered it. I was just happy to be with my parents. In San Jose, it was warmer and the people were more diverse. I grew up with Vietnamese and Mexican Americans, among the working-class, immigrants, refugees, and Catholics. The Vietnamese were a significant part of the population, striving to survive and get ahead. My parents opened the second Vietnamese grocery store in the city (their friend opened the first). Throughout most of the 1980s, they worked twelve to fourteen hour days every day of the year except for Easter, Christmas, and Tet. I went to public school, then Catholic school. At night I helped with the accounting for the grocery store. I readied the checks and food stamps and welfare vouchers and I added up the results. I knew the numbers of the calculator by heart. My parents told me that if we were still in Vietnam, I’d be drafted and sent to Cambodia. Some of my grandparents in Vietnam died and I didn’t understand my parents’ sorrow or why I had to wear a white headband. My parents were shot in an armed robbery at their store on Christmas Eve. In high school, a gunman broke into our house and pointed his pistol in my face. My mother ran screaming into the street and saved our lives. I couldn’t wait to leave and go far away to college. That was what it was like to grow up in San Jose, California.

You saw a lot of trauma in your community related to the war, but you also experienced many positive things such as family and friendship. Can you tell us how the positives affected your life? How have you assimilated (or not) into American life?

The Vietnamese community in the United States is as complicated as the one in Vietnam. On the one hand, the Vietnamese people are very hospitable and welcoming. They will always welcome you into their home and offer you food and drink. Friendships are eternal and loyalty is deeply valued. Blood can never be dissolved and family can always be counted on. I have absorbed those values. On the other hand, the Vietnamese people are also prone to gossip and to cheat. They know it and they cannot do anything about it. They will cheat strangers and relatives, and they will gossip about enemies and loved ones. Blood can never be dissolved and family can be treacherous. I cannot separate the good and the bad when talking about Vietnamese people, just as I cannot when talking about American life. Like my novel’s narrator, I see both sides. This means I am never quite at home, even in an American culture that I am assimilated into. Like my narrator, if you heard me over the phone, you would think I am American born and bred. America is my home. At the same time, I am always aware of the failures and hypocrisies of the United States.

How long have you been with the University of Southern California? Do you have many Vietnamese or Vietnamese-American students?

I have spent nineteen years—my entire career—at USC. Unfortunately, I don’t have many Vietnamese or Vietnamese American students, even when I teach on the Vietnam War. Most of them are in the sciences and seem to be pragmatic. The Vietnam War may be too disturbing for them to think about, or else it is simply irrelevant. At the same time, they also do not seem to be very interested in my other topics, Asian American studies or American literature and culture. I have greater numbers of other Asian American students in all these classes, as well as greater numbers of Asian international students in my Vietnam War classes.

What is the attitude towards Vietnamese heritage on campus? What is the Vietnamese

community there like?

There is a small group of students interested in Vietnamese culture. They have a Vietnamese Student Association. I think for them that Vietnamese culture means two things. One part of it is tradition, which they exhibit in their annual culture shows. By tradition I mean things like ao dai, peasant dances, village songs, and food. Another part of their heritage is the Vietnamese American community, which means nearby Little Saigon, filial piety, the flag of the south. For a while there was a Vietnamese International Student Association for foreign students. Perhaps it still exists. The two populations do not communicate with each other and only came together once, in my knowledge, when the issue of the Vietnamese flag became a controversy. The campus was flying the current red flag in its international display, and a community activist came and stapled the yellow flag over it. The two student associations convened to debate the flag, the war, and history. The foreign students said that they understood the perspective of the Vietnamese Americans, but that they wanted to get over the past and to reconcile. The Vietnamese Americans said that they could not get over the past, that the pain of their parents still matters to them. In their own way, the Vietnamese students on campus—American and foreign—embody the tensions between the Vietnamese diaspora and Vietnam. This, too, is a part of our Vietnamese heritage and our definition of what a Vietnamese community is.

Your new book is disturbing, fascinating but also a little funny. Are any of the characters based on real people?

Lots! Francis Ford Coppola is easily recognizable. Nguyen Cao Ky, Madame Nhu, Hoang Co Minh, Lynda Trang Dai, and Nguyen Ngoc Ngan provided some of the inspiration for other characters.

Guilt and betrayal are big themes in the book. Do you think these are natural to the human condition?

Yes. Every culture and nation has a history of guilt and betrayal. The Vietnamese and the Americans are not unique. This is why I think the novel is not only about the Vietnam War and what Americans and Vietnamese did to each other and to themselves. The questions they faced, and the actions they undertook, expressed that more fundamental human condition of having to make a choice and living with its consequences.

What is your next project? Are you working on another novel?

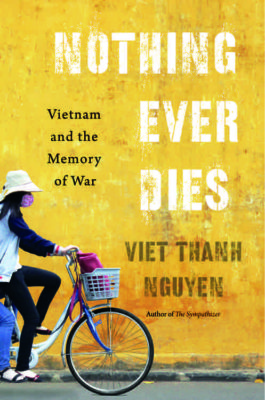

I’m editing the proofs for my next book, Nothing Ever Dies: Vietnam and the Memory of War. It comes out from Harvard University Press in March 2016.

I think of this book as the critical companion to my novel. As soon as I am done with the proofs, I resume writing the sequel to The Sympathizer. I am thrilled about that, as it took me thirteen years to write Nothing Ever Dies.

Vincent Lam, a Vietnamese-Canadian author and physician has called your book “remarkable and brilliant.” What advice would you give to someone who wants to follow in your footsteps either as an author or outstanding academic?

Find something that you can believe in. After that, persist. What truly matters to you is something that may not be achievable in five years or ten years or twenty. That’s the difference between a profession and a vocation. A profession offers you external measures and rewards, defined by other people. A vocation and its value is something only you can determine.

This content is also available in: Vietnamese