Author Viet Thanh Nguyen is interviewed by Goodreads.

“I am a spy, a sleeper, a spook, a man of two faces.” In his debut literary thriller, The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen introduces his complicated hero, known only as the Captain. A half-Vietnamese double agent and Communist sympathizer, the Captain is the trusted right-hand man of a South Vietnamese general. In the final chaotic days of the Vietnam War, as Saigon falls and the Viet Cong take control of the city, the Captain narrowly escapes with the general’s entourage to Southern California, where the aggrieved group of refugees begins new lives and plots to reinvade Vietnam. Nguyen’s story illuminates the aftermath of war and the shifting of identity, as the wily Captain makes harrowing choices to maintain his cover.

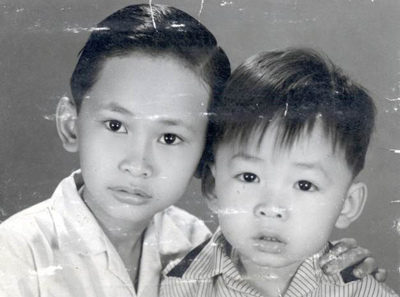

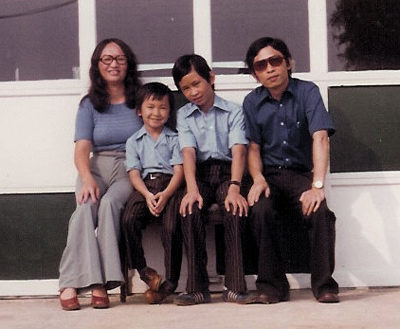

Los Angeles writer Nguyen is an associate professor of English and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California and the author of Race and Resistance: Literature and Politics in Asian America. He shares some childhood photos—his family left Vietnam for Pennsylvania in 1975—that inspired his storytelling in The Sympathizer.

Goodreads: If called upon to do so, do you believe you could lead a double life, as the Captain does?

Viet Thanh Nguyen: This was a question I often thought of in college as I read the history of the war. If I had been born 20 years earlier, I would have been of the generation that had to make difficult political and personal choices, which could lead to both tragedy and glory. I was spared having to decide, which meant that when I was younger, I believed that I could have made that tough choice and sided with the revolution, even going underground. Now I think I would have been too much of a coward to do anything so daring. In a more allegorical way, though, the Captain’s plight of being a man with two faces is also a commentary on how many of us live in that fashion, if not so dramatically. I’ve certainly often felt that I live a double life, that I have different faces for different occasions, that I am a spy in the worlds of other people. Hopefully I’m not alone in this.

GR: Your protagonist is a man divided—by his own heritage, by political ideology, and more. How did you develop the character of the Captain?

VTN: Wars and other conflicts happen at least partially because people can’t see things except from their own side. They don’t have any doubts about what they believe in and who “us” and “them” are. I wanted to write a novel that would criticize this way of thinking, so I needed a character who was divided in his beliefs, who had doubts, who could sympathize with his enemies. Making him Eurasian gave me a cultural excuse for why he might be divided in his thinking and beliefs, since people of mixed-race descent often feel as if they are torn between two sides, or at least are made to feel that way by others. At the same time, I didn’t want him to be the stereotypical mixed-race person who suffers tragically because of his descent, like the tragic mulattoes of American literature. So he also had to be someone who was insightful about his condition, who was self-aware, and who was humorous. Once those traits were in place—once he had his voice—the novel was relatively easy to write, as all I had to do was follow him and what he would logically do when confronted with certain scenarios.

GR: So much is written about the Vietnam War, yet the postwar period feels comparatively neglected. What inspired you to choose this setting for your novel?

VTN: I grew up in America during the postwar period, surrounded by Vietnamese refugees and their stories. For them the war hadn’t ended. Many of them still suffered and longed to take their country back. Most Americans had no idea how much the war affected these people. Meanwhile, in Vietnam, the state considered these people to be traitors for having fled the country, and the state continued to wage war by imprisoning and punishing its enemies. So I wanted to make the neglected postwar experiences of the southern Vietnamese refugees, and the ones they had left behind in Vietnam, the core of the story, not least because their stories were also very interesting. There really was an effort to launch an invasion of communist Vietnam through Thailand, and there were widespread rumors that the first Vietnamese pho noodle chain was funding this effort. And there really was a concerted effort to ameliorate the pain of the past by flocking to watch a song-and-dance revue and by turning weddings into lavish events where people could sing pop songs and get drunk on cognac and nostalgia. There really were thousands sent to reeducation and thousands more who took to the ocean to flee Vietnam. All of these things and many more historical details make their way into the book. And of course the postwar period is when Americans refought the war on movie screens, which is in the book, too. Through satirizing American cinematic fantasies of the war, I could also give my take on the actual fighting of the war itself and its consequences for the Vietnamese.

GR: As a scholar, you are also skilled in a very different kind of writing. How do these two halves of your career echo or reinforce each other? And what role does fiction play in the larger political and cultural dialogue?

VTN: I’m finishing an academic book now titledWar, Memory, Identity. I think of it as the critical bookend to a set of concerns expressed in the title, with this novel being the fictional bookend. My thinking about these concerns has been worked out on a creative continuum between the critical and the fictional, where my academic research has seeped into the novel, and where my fiction writing has transformed how I write and think academically. Many of the formal decisions I made in the novel are an expression of my academic thinking, like making my narrator struggle constantly with what it means to be an other, or ensuring that the novel does not end in America. Most books like mine would be expected to conclude in America because it is the promised land of the American Dream, especially versus poor, troubled Asia. I reject that narrative, which I’ve come across too often in my research. Likewise, my self as a critic has benefited from dealing with a narrator who sees everything from many sides. Even in academic research, there’s too often the tendency to see things from one side, which has an impact on both scholarly conclusions and scholarly writing. If, as a scholar, you’re only interested in one side and talking to one side, you also can tailor your writing to speak to a narrow audience and rely on jargon. Being a fiction writer has made it difficult for me to do that, because I constantly worry about how accessible my writing is, even when dealing with complicated subjects. Fiction can impact the larger political and cultural dialogue when writers take on these subjects and render them dramatically compelling, which is something academics have a hard time doing.

GR: What’s next for you as a writer?

VTN: The sequel to The Sympathizer. I feel like I’m not done with him and that he’s not done with me. And then there’s this short story collection I’ve worked on for a decade before The Sympathizer. I wish I were done with it, but having learned so many things from writing the novel, I have to go back and revise that collection.